At age 13, Ian Manuel was arrested and charged with a nonhomicide offense that resulted in him being sentenced to die in a Florida prison.

EJI took on his case and argued that it is cruel and unusual punishment to sentence a 13-year-old child to life imprisonment with no chance for parole. EJI won Mr. Manuel’s release in 2016.

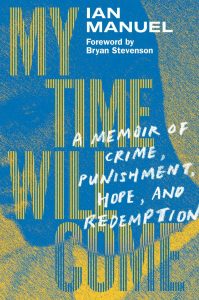

Today, Mr. Manuel has released a powerful memoir documenting his struggle from childhood in Tampa’s most violent and abusive housing projects, through 18 years of solitary confinement, to freedom.

My Time Will Come: A Memoir of Crime, Punishment, Hope, and Redemption, tells of the abuse, neglect, and violence Ian suffered from infancy up to the moment in 1990 when 13-year-old Ian was directed by older juveniles to commit a robbery.

During the botched robbery attempt, a woman suffered a nonfatal gunshot wound. Ian turned himself in to the police and was charged as an adult with armed robbery and attempted murder.

Ian’s attorney instructed him to plead guilty and told him he would receive a 15-year sentence. Ian accepted responsibility for his actions and pleaded guilty but was sentenced to life imprisonment without possibility of parole.

Ian became one of the youngest children condemned to die in prison in the U.S.

Because he was a very small boy, state prison officials decided to place Ian in solitary confinement, where he remained for the next 18 years. The extended isolation was extremely challenging, abusive, and destructive.

With few contacts on the outside, Ian reached out to the shooting victim, Debbie Berkovits, to ask for her forgiveness, which she gave. A remarkable relationship emerged in which Ms. Berkovits became a supporter for a reduced sentence for Ian. But courts were nonresponsive.

EJI took on Ian’s case as part of our effort to end excessive punishment of children. While his case was pending on appeal, the Supreme Court decided in Graham v. Florida that children cannot be sentenced to life imprisonment without parole for nonhomicide offenses like Ian’s.

But the State of Florida argued that Graham did not apply to Ian’s case because attempted murder is a homicide offense even though no one was killed. EJI challenged that argument on appeal and won a unanimous ruling rejecting the State’s argument and vacating Ian’s life-without-parole sentence. The State appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Court denied the State’s request for review.

At his resentencing hearing, Ian told the court that he and Ms. Berkovits have been “waiting for the justice system to catch up to my remorse and her forgiveness.”

In 2016, Ian was released from prison after 26 years of imprisonment. He celebrated his freedom by having dinner with Ms. Berkovits and EJI staff.

Five years later, Mr. Manuel is using his writing talents to share his story of survival and advocate for ending solitary confinement for children.

“For 18 years I didn’t have a window in my room to distract myself from the intensity of my confinement,” he wrote in an op-ed for The New York Times. “I wasn’t permitted to talk to my fellow prisoners or even to myself. I didn’t have healthy, nutritious food; I was given just enough to not die.”

Conditions like these put people held in solitary confinement at increased risk for self-harm and suicide, exacerbated mental illness, and higher rates of death after release.

“Prison is a beast, but solitary confinement definitely did more damage to my soul than being in the general prison population would have,” Mr. Manuel told the Los Angeles Times.

His life in solitary confinement was one of “complete hopelessness,” Ian said in video testimony at a 2007 hearing before a federal judge in Jacksonville. With no programs or classes, no visitors, phone calls, or human touch, deprived of books, magazines, TV, and radio, and barred from talking or even looking out of his cell door, Ian began cutting himself when he was 17. “It gave me relief from the intolerable numbness,” he said.

Hopelessness drove him to go on a hunger strike, overdose on pills, and set himself on fire. The prison’s response was to take away his clothes, mattress, and sheet. After Ian testified about trying to kill himself “to end the pain,” the St. Petersburg Times reported, the federal judge was so upset he had to call a recess and leave the courtroom.

The U.S. is the only advanced nation that uses prolonged isolation as a routine tool of prison management. United Nations standards on the treatment of prisoners prohibit solitary confinement for more than 15 days, declaring it “cruel, inhuman or degrading.”

President Barack Obama banned solitary confinement for juveniles in the federal prison system in 2016, writing that it can have “devastating, lasting psychological consequences,” including an increased risk of suicide, especially for juveniles and people with mental illnesses.

But too many states failed to follow the federal government’s lead, and solitary confinement is still common across the U.S.—even for children. It is estimated that at least 80,000 incarcerated men, women, and children are held in some form of isolated confinement on any given day.

“I witnessed too many people lose their minds while isolated,” Mr. Manuel wrote. Just as he used his imagination to survive 18 years in isolation, he’s now determined to use his writing to make sure no other child has to endure what he did.

“No human being should have to live through what I lived through.”