A new report by the U.S. Interior Department investigating over 400 former Federal Indian boarding schools documents some of the many abuses that thousands of Indigenous children were subjected to between 1819 and 1969.

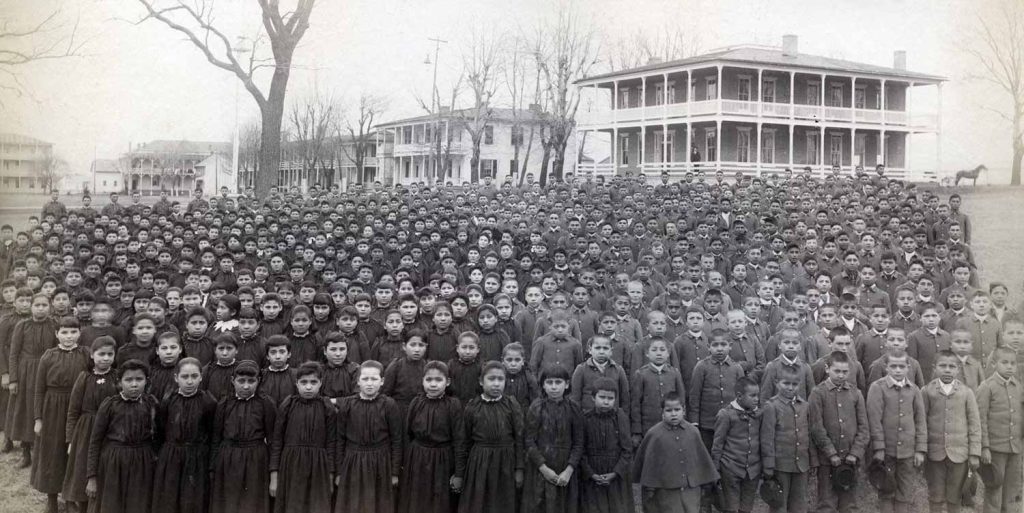

The report is the first of its kind and was commissioned by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland last June following the discovery of a mass grave on the site of a former Indian school in British Columbia. Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, who put together the report, said the Department identified 408 schools across 37 states, including 21 schools in Alaska and seven in Hawaii.

In nearly all of the schools, severe abuse was widespread. The investigation uncovered at least 53 burial sites for children across the schools and examined 19 schools in particular that accounted for over 500 child deaths. Mr. Newland noted that the toll was likely much higher and that he expected this figure to increase as the Department continues its research.

A History of Forced Assimilation and Displacement

In 1819, the U.S. Congress enacted the Civilization Fund Act, which paid missionaries and church leaders to help establish government-run schools designed to “civilize” Native children.

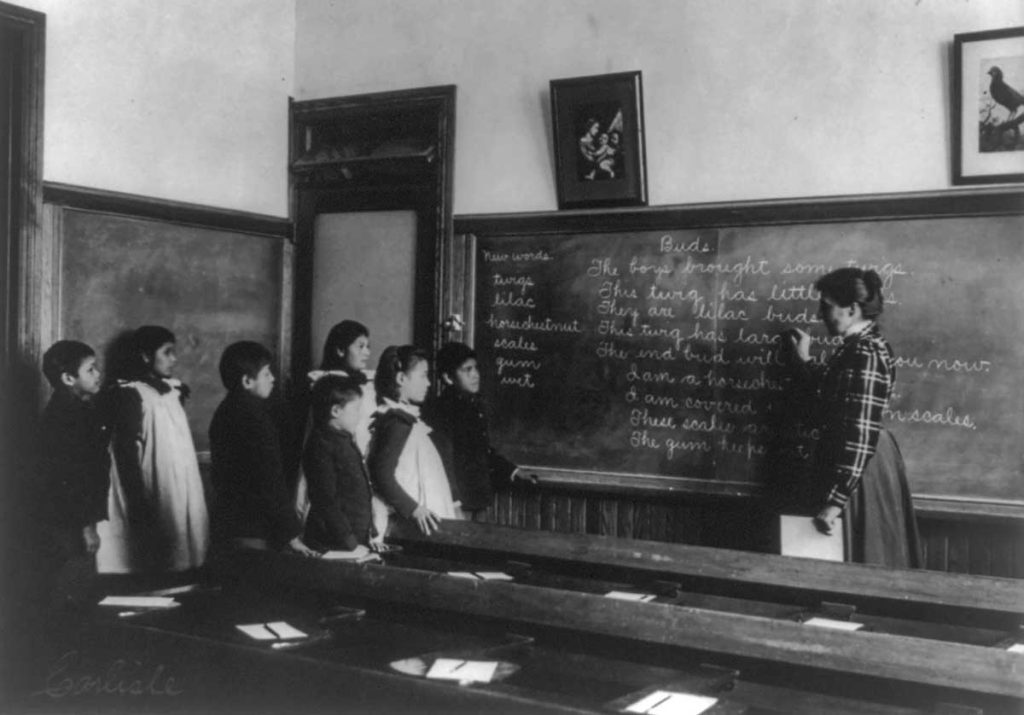

For nearly two centuries, thousands of Indigenous children—some as young as four years old—were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools far from their families. The federal schools then subjected the children to “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” for forced assimilation: they were given English names, forced to cut their hair, and forbidden from speaking their Native languages.

Students received vocational training but very little academic instruction, with the expectation that they would make their living as farmers or manual laborers. Conditions in many schools were poor and abuses were rampant. According to the Department report, punishments like solitary confinement, flogging, food withholding, whipping, slapping, and cuffing were regularly employed to enforce boarding school rules.

/

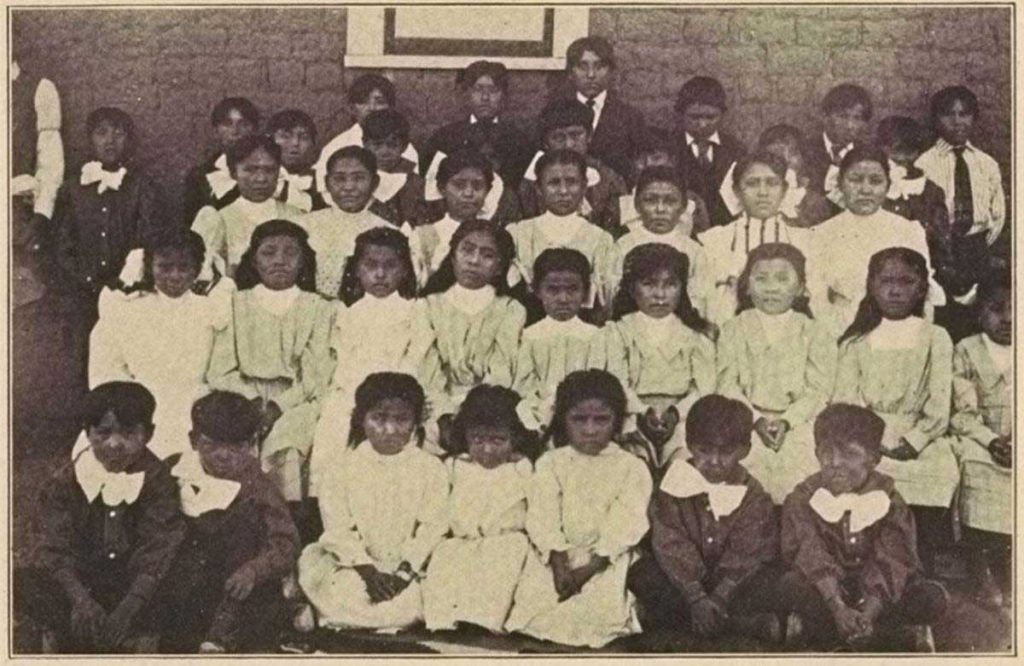

Children outside the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

John N. Choate via Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource CenterA First Step Towards Truth and Justice

Ms. Haaland—who is the first Native American woman to head the Department and whose own grandparents were forced to attend government-run schools—called the report an initial step in a comprehensive investigation that she hopes will ultimately help address the intergenerational trauma many Indigenous people grapple with to this day.

“It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal,” she said during a news conference.

In response to the findings of the report, and as part of the Department’s broader initiative to reckon with this history, Ms. Haaland announced the launch of “The Road to Healing,” a year-long tour across the U.S. that will give boarding school survivors and their families the opportunity to share their stories, receive additional support, and “facilitate collection of a permanent oral history.”