Every day in the U.S., thousands of children across the country attend schools named in honor of Confederate leaders who fought to preserve slavery and racial hierarchy in America. Simply by going to school, young people are taught to embrace the names, likenesses, and symbols of men who fought a brutal war against the U.S. in order to preserve white supremacy.

EJI has identified more than 240 schools across the U.S. that currently bear the name of a Confederate leader. These schools are located in 17 states, from Georgia to Minnesota to California, and include public elementary, middle, and high schools. Significantly, about half of these Confederate-named schools serve student bodies that are majority Black or nonwhite.

/

Plant City, Florida

/

Mascot for Dixie Heights High School in Edgewood, Kentucky

/

Hazelhurst, Georgia

/

Baytown, Texas

/

San Angelo, Texas

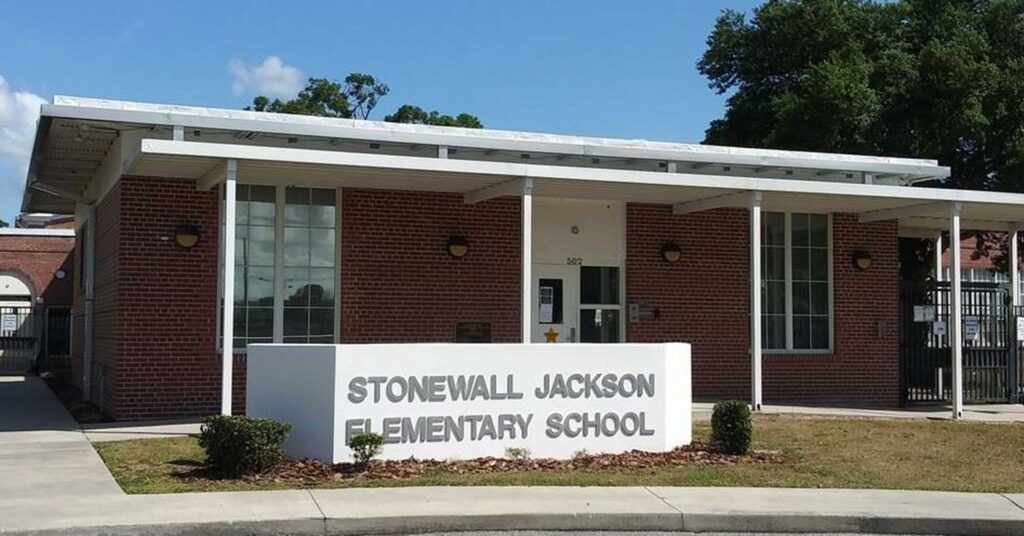

In Plant City, Florida, more than 85% of the students attending the Stonewall Jackson Elementary School are nonwhite. Their school was named after Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, a man who not only commanded the Confederate Army but also bought and sold enslaved Black people.

Much farther north in East Wenatchee, Washington, a majority nonwhite student body attends Lee Elementary School, which was named in 1955 after Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who led the fight for the Confederacy and argued that the enslavement of Black people was “necessary for their instruction as a race.” And despite the fact that their school is named after Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president who led the effort to preserve enslavement of Black people, almost all of the students who attend Davis Elementary School in Greenwood, Mississippi, are African American.

Historically, the practice of naming schools to honor the architects and defenders of slavery has been part of a broader effort to maintain racial hierarchy in the U.S. In particular, many schools were given Confederate-themed names in the 1950s and 1960s as Southern states mounted what they termed “Massive Resistance,” a coordinated effort by governors, legislators, and other white leaders to resist the racial integration of public schools. As federal law increasingly required school desegregation, white communities built new schools—schools that were either explicitly or implicitly intended for white children only—and named those schools after white Southerners who were notorious racists.

Immediately after the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Southern leaders invoked the Civil War to make plain their opposition to the Court’s ruling. Georgia Governor Herman Talmage threatened, “We’re not going to secede from the Union, but the people of Georgia will not comply with the decision.” An editorial in South Carolina’s News and Gazette warned that the ruling “has cut deep into the sinews of the republic.” At the same time, the South saw a resurgence of Confederate iconography. Georgia added the Confederate battle flag to its state flag in 1956 and throughout the country scores of new monuments to the Confederacy and its leaders were erected.

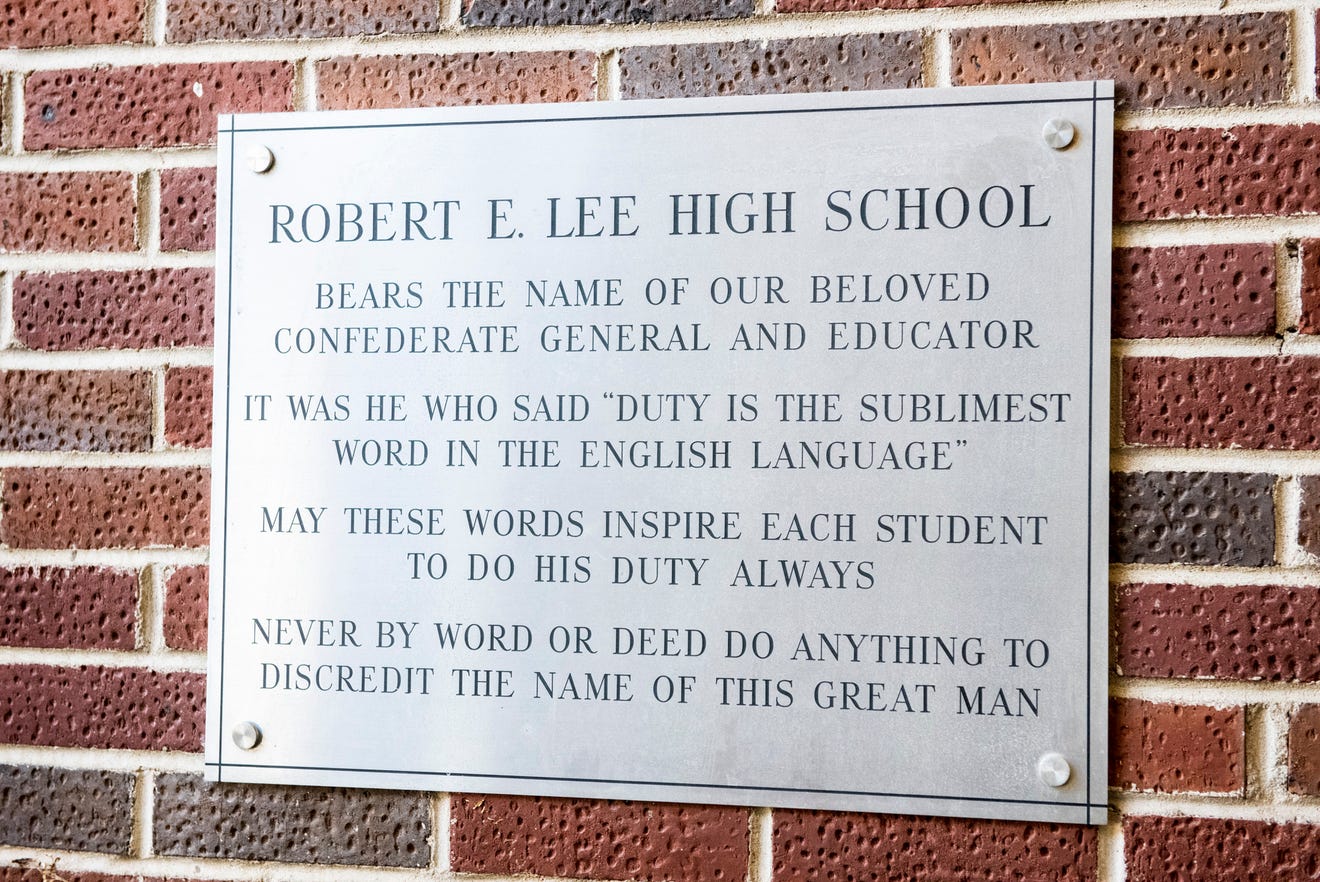

Efforts to resist racial integration varied widely across the country. In Montgomery, Alabama, Robert E. Lee High School opened its doors in 1955 as an explicitly whites-only school in direct defiance of the Brown decision.

This placard greeted students at Robert E. Lee High School in Montgomery, Alabama, until 2020.

Later, the approach was more subtle but hardly less clear. In 1968, Montgomery opened Jefferson Davis High School as nominally available to children of all races. A federal court later observed, however, that the school was clearly intended to serve white children only: it was located “in a predominantly white section of Montgomery,” was built to accommodate only “the number of white students residing in the general vicinity,” and featured “a school name and a school crest [featuring the Confederate battle flag] that are designed to create the impression that it is to be a predominantly white school.”

Today, one of the legacies of slavery and our failure to overcome racial hierarchy is that many Black children attend public schools named after people who enslaved and trafficked those children’s Black ancestors. The absence of any reckoning with this history has had serious consequences for America. Bias, racial inequality, and unfair treatment of people of color is evident in many spaces.

Since 2014, more than three dozen schools in the U.S. have been renamed to eliminate references to the Confederacy. In July 2020, the Montgomery County Board of Education in Montgomery, Alabama, voted to rename Jefferson Davis High School, Robert E. Lee High School, and a third school—Sidney Lanier High School—amidst national protest and conversation regarding our nation’s history of racial inequality.

EJI believes that understanding and overcoming the opposition to racial equality, integration, and civil rights is central to confronting the continuing challenges of racial inequality today.