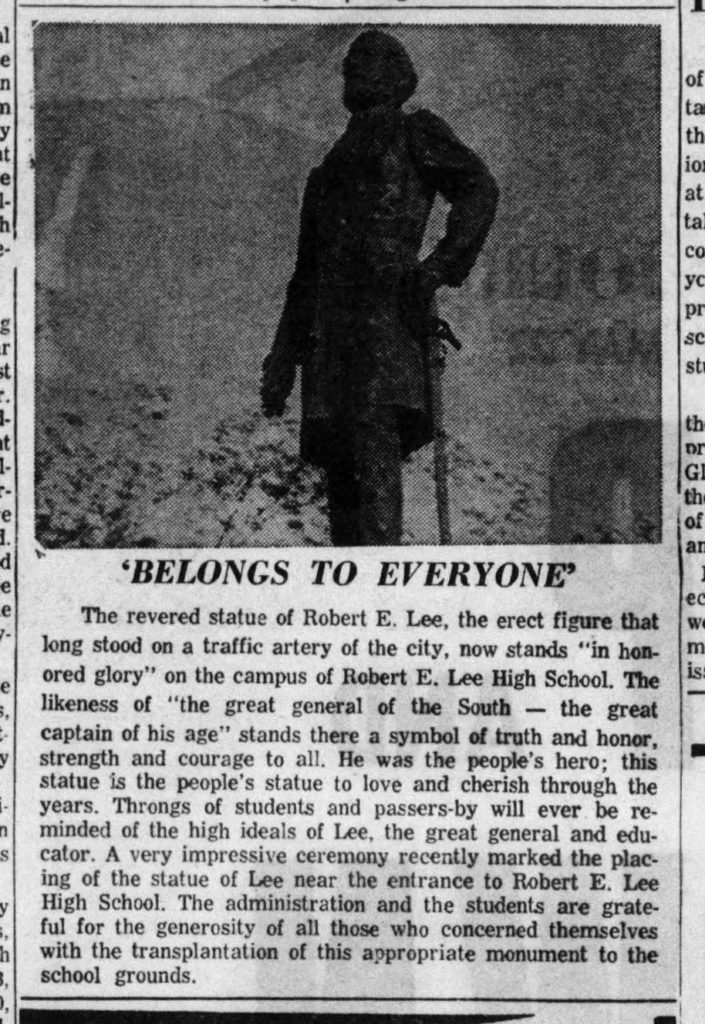

This week, Montgomery police arrested and charged four people with removing a statue of Robert E. Lee from atop a pedestal at the entrance of the local high school bearing his name. For 60 years, the Confederate General’s likeness had held its prominent place on the once all-white public school’s campus—even though Lee commanded forces in a war to maintain the enslavement of Black people, and even though more than 8 in 10 of the school’s students are now Black. After years of unsuccessful calls to remove or relocate the statue, the pedestal today stands empty. Officials charged with charting the path forward from here should know that their decision will be no more neutral than the decision to place the statue in 1960.

The history of Robert E. Lee High School, and its relationship to this statue, is rooted in the massive resistance campaign that white people in Alabama and throughout the South waged to maintain school segregation. On May 17, 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously invalidated racial segregation in public education, reasoning that segregated public schools were “inherently unequal” and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. By overturning the nearly 60-year-old precedent of “separate but equal,” Brown threatened to dislodge a cornerstone of the Southern racial caste system.

Most white Americans, especially in the South, supported segregation; Brown outraged white segregationists as much as it energized civil rights activists. Throughout the South, where state constitutions and state law mandated segregated schools, white people decried the decision as a tyrannical exercise of federal power. In Alabama, segregation was universal and deeply entrenched, and the 1901 state constitution mandated public schools separated by race. (After two failed electoral attempts at change, that language remains in the state constitution today.)

Opposition to Brown sparked a mass movement, and white Americans implemented a strategy of “massive resistance” that used tactics like legal delay, violent intimidation, and bold defiance. In fall 1955, one year after Brown was decided and just months after the Court ordered segregated schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” Robert E. Lee High School opened in Montgomery as a brand new, state-of-the-art campus—for white students only. An August 1955 Montgomery Advertiser story lauded the $1.25 million building and $125,000 of equipment set to serve nearly 800 pupils in the first year. Reporting the inaugural students’ excitement alongside several photos of smiling white teens, the article noted, “It’s not every teenager who gets to christen a new school. In fact, its been about 26 years since Montgomery had a new white high school.”