Lamar “Ditney” Smith knew the dangers of helping Black citizens vote in Mississippi in 1955. He had received death threats, and knew about many Black people who had been lynched in his county. In May, white men had killed another Black activist, the Rev. George W. Lee, for registering voters in Mississippi. State Democratic party chairman Thomas Tubb declared, “We don’t intend to have Negroes voting” in the August primary, and said those who did vote might get “a whipping.”

But Mr. Smith, a 63-year-old World War I veteran and farmer, kept at it. He encouraged Black citizens to vote by absentee ballot, a seemingly safer option than going to the polls.

Lamar Smith

On Saturday morning, August 13, 1955, Mr. Smith was home at their farm with his wife, Annie, when someone called and told him to come to the county courthouse in Brookhaven.

Mr. Smith was crossing the courthouse lawn at 10 am, absentee ballots in hand, when three white men surrounded him. One pressed a .38-caliber handgun against his ribs and fired.

None of the dozens of onlookers came to Ditney Smith’s aid as he lay dying. A white Brookhaven man, Tex Sample, never forgot hearing someone nearby say, “Nobody carries that n—r to no hospital.”

The sheriff heard the shots and saw a blood-splattered white man walk away but did not stop him. He took eight days to arrest three white men. They were released after a parade of witnesses, some of whom had been within 30 feet of the confrontation, falsely told a grand jury they had seen nothing.

NAACP investigators determined that Mr. Smith had walked into a trap. A half-century later, a witness told the FBI that three men had delivered whiskey to “someone who knew Smith and was instrumental” in persuading him to come to the courthouse.

After the murder, a notary public who had assisted Black voters said he was warned to stop, lest he “wind up like Ditney Smith.”

Lamar Smith was only one of the many Black leaders murdered in the 20th century in the South, in places where the numbers of Black eligible voters could have changed the outcome of elections. As was so often the case, no one was held accountable for any of the killings explored in this article. The killers included white policemen, sheriffs, businessmen, even a legislator—all part of the Jim Crow system aimed at disenfranchising Black voters. Local prosecutors usually refused to bring charges even though they knew the perpetrators of this violence. When there were prosecutions, all-white juries acquitted the guilty. The dead were blamed, falsely accused of being “rabble rousers” and Communists. Their families fled North, leaving behind their homes, farms, and businesses.

FBI agents and local police officers examine a pickup truck in Natchez, Mississippi, after a bomb blast killed Wharlest Jackson, an activist and the treasurer of the Natchez NAACP. (AP)

So many civil rights-related killings went unsolved that in 2007, a law named for Emmett Till launched FBI reinvestigations—but many of the cases were deemed not “prosecutable.” Witnesses and suspects had died, and evidence was gone.

Those who were murdered were fathers and mothers, teachers, ministers, farmers, undertakers, grocers, and laundry workers—upstanding members of their communities who risked their lives to ensure that Black Americans could exercise their constitutional right to vote in places where that right had been denied to them for generations.

“Political violence against Black leaders where no one is held accountable was a defining feature of American politics in the 20th century,” said EJI Executive Director Bryan Stevenson. “The failure to hold anyone accountable makes entire systems—state and federal—complicit and implicated in the perpetuation of this kind of violence. And rather than remedy this problem, there continues to be entrenched resistance to even recognizing the problem.”

“Lamar Smith was extremely courageous, as were many others,” Mr. Stevenson said. “He gave his life to advance democracy in this country and in return we gave him no justice.”

Lamar Smith’s grandchildren attend a monument dedication ceremony at EJI’s Peace and Justice Memorial Center on April 29, 2019. (Jonece Starr Dunigan)

‘As if they had killed only a rabbit’

On June 12, 1939, Elbert Williams and four other Black citizens of Brownsville, Tennessee, organized their town’s first NAACP branch. They set out to encourage Black residents—who were the vast majority of Brownsville’s 19,000 citizens but had been disenfranchised for decades—to register and vote.

When the NAACP branch president and four members visited the local registrar’s office on May 6, 1940, to ask about registering to vote in that year’s presidential election, they were given the runaround and told registration did not begin until August.

The next day, a deputy sheriff warned two NAACP members to stop “encouraging Negroes to vote or there would be trouble.”

A “mob spirit,” as an NAACP member put it, took hold. On June 15, at around 1 am, some 60 white men led by Brownsville’s night marshal and nominee for sheriff, Samuel “Tip” Hunter, another police officer, and other local officials and businessmen abducted NAACP executive committee member Elisha Davis from his home, drove him to a river bank, terrorized him into naming other members, and ran him out of town under threat of death.

Charter members of the Brownsville, Tennessee, NAACP. Elbert Williams stands at the far left. (The Jackson Sun)

The entire Black community was threatened with reprisals. Milmon Mitchell of the Jackson, Tennessee, NAACP branch, 25 miles from Brownsville, wrote to the national office: “The whites are discharging Negroes from their jobs, threatening to discontinue Negro teachers—merchants and banks are refusing credit to all known members in our organization.”

On June 20, 1940, someone told the night marshal, Tip Hunter, that Elbert Williams, a relative of Elisha Davis’s, had been overheard proposing a meeting between the Brownsville and Jackson NAACP branches. Mr. Williams, 32, was a boilerman at a laundry where his wife, Annie, was a presser. That night, the couple had just listened to the radio broadcast of heavyweight champion Joe Louis’s triumphant prizefight at Yankee Stadium and were getting ready for bed when they heard pounding on their door.

Mr. Hunter and two other white men were outside. They had Elisha Davis’s younger brother, Thomas, in their car. The three white men forced Mr. Williams into the car barefoot and in his pajamas. At the police station, Tip Hunter interrogated Mr. Williams and Thomas Davis for hours about NAACP activity before releasing Thomas Davis, who left town.

By the next morning, Elbert Williams had not come home.

When he learned of the escalating terror in Brownsville, NAACP Special Counsel Thurgood Marshall telegraphed President Franklin Roosevelt and pleaded for federal intervention. The NAACP implored Tennessee Gov. Prentiss Cooper to take “immediate action” to protect Brownsville’s Black citizens.

Neither federal nor state protection was forthcoming.

Two days later, Mr. Marshall sent a telegram to the governor: “We have been advised that the body of Mr. Williams has been found floating in a river near Brownsville.”

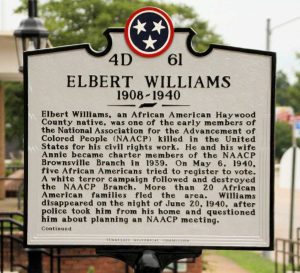

A historical marker in Brownsville, Tennessee, honoring Elbert Williams. (John Ashworth)

Summoned by the coroner to the banks of the Hatchie River, Annie Williams identified her husband. His head was swollen to twice its size, he’d been badly beaten and bruised, and there were two holes in his chest that could have been bullet or stab wounds. A rope around Mr. Williams’s neck was tied to a log.

A coroner’s inquest, with six white men gathered at the river, concluded on the spot that the death was “caused by foul means by persons unknown.” At the coroner’s direction, the body was buried that day in an unmarked grave. No autopsy was conducted.

A Jackson newspaper quoted Tip Hunter as saying he had picked up Mr. Williams and Thomas Davis, questioned them for three hours, and “turned them loose.” He said he’d seen nothing “like a lynching party, either white or Negro.”

NAACP investigators gave the Justice Department sworn affidavits from witnesses who saw Mr. Hunter and another law enforcement officer abduct Mr. Davis and Mr. Williams. But an all-white grand jury returned no indictments.

Finally, after repeated pleas from the NAACP and with the evidence going cold, the FBI investigated. Agents brought Tip Hunter along to interviews with witnesses in Brownsville—and, not surprisingly, came away without evidence to bring charges.

No Black citizens of Brownsville registered to vote in the 1940 election—the fear was too great. The Brownsville NAACP dissolved. At least 20 Black families moved away.

In a scathing press release faulting the government for inaction—and the ongoing reign of terror against Black voters—Mr. Marshall quoted a local NAACP representative: “Members of the mob that lynched Elbert Williams can be seen in Brownsville each day going about their work as if they had killed only a rabbit. Tip Hunter, the leader of the mob, recently took office as sheriff.”

In 1942, federal investigators closed the case for what they claimed was lack of evidence. Four years later, I.B. Nichols, assistant director of the FBI, acknowledged that the agency had not adequately supervised the case, that it had dragged its feet and failed to follow up on leads.

White residents target a husband and wife on Christmas

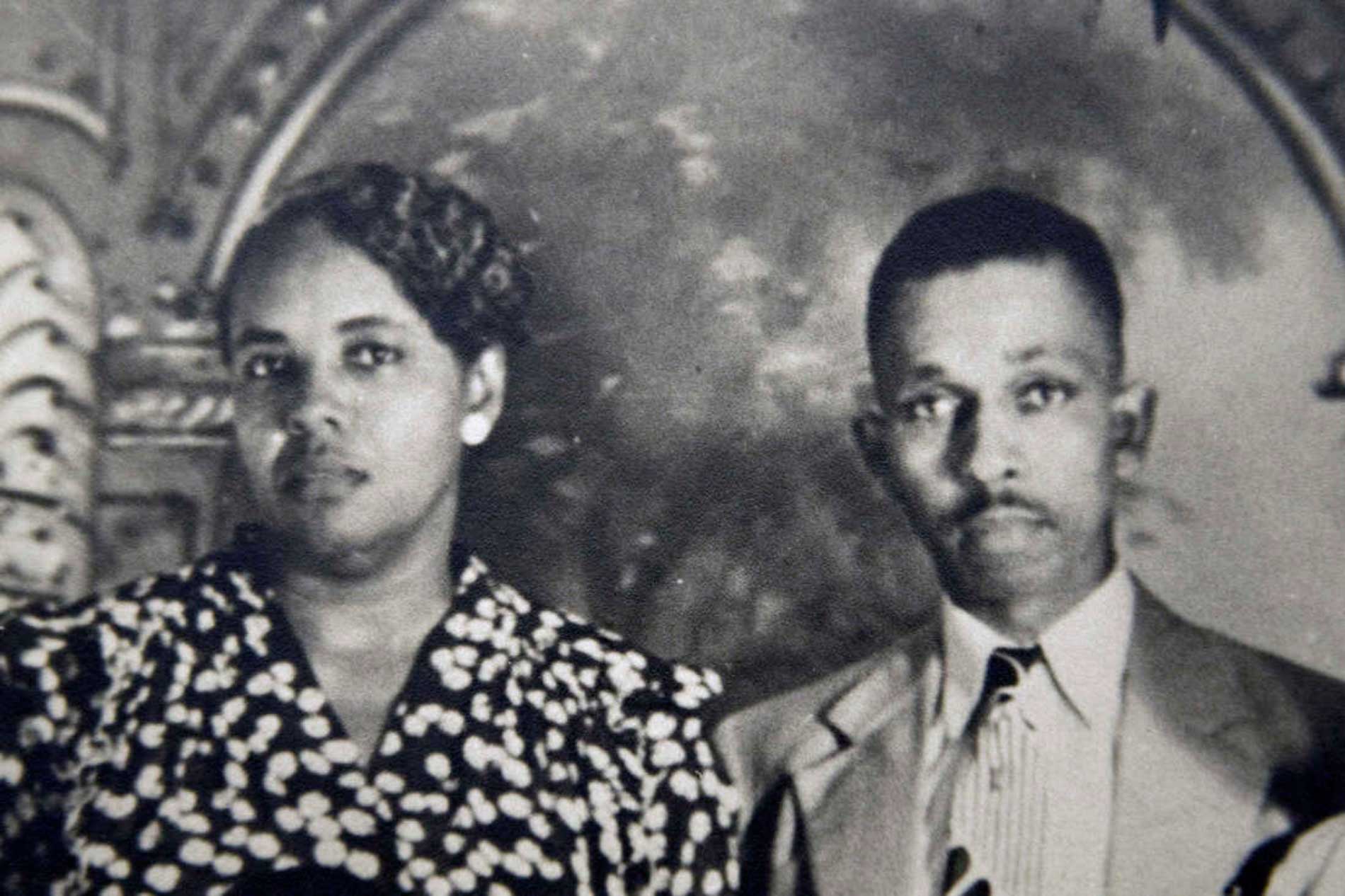

Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette V. Moore, both schoolteachers in Mims, Florida, founded Brevard County’s NAACP in 1934. They were fired from their teaching jobs after they campaigned for voting rights and equal pay for Black teachers. It didn’t stop them.

As executive secretary of Florida’s NAACP, Mr. Moore helped the organization grow to 63 branches and 10,000 members, and register 116,000 voters—31% of Black voting-age Floridians—in the six years after the Supreme Court’s 1944 decision outlawing white primaries.

Harriette V. Moore and Harry T. Moore in the late 1940s. (Getty Images)

He led a successful campaign to overturn an all-white jury’s wrongful convictions of four Black men in a 1949 rape case. When a sheriff shot two of the defendants, one fatally, before they could be retried, Mr. Moore called for him to be suspended and charged with murder.

Six weeks later, on Christmas night, 1951—the Moores’s 25th wedding anniversary—a bomb exploded under their bed. Harry died that night, Harriette nine days later.

The couple’s activism had made them a KKK target. The FBI learned that one of four implicated Klansmen had drawn a floor plan of the couple’s home, but no one was ever charged in the case.

‘Somebody had to lead’

In the Mississippi Delta town of Belzoni, George and Rosebud Lee were a success story. She ran a small printing business out of their house. He preached at four churches, owned a grocery store, and belonged to Mississippi’s Regional Council of Negro Leaders. He became the first Black voter to register in Humphreys County in decades. Along with some 60 other residents, he and his friend and fellow grocer Gus Courts founded an NAACP branch in 1954. Within a year they registered 92 Black voters.

The Rev. George Lee (Mississippi Today)

Thanks to the Jim Crow system, less than 5% of Mississippi’s voting-age Black citizens were registered to vote in 1955. In 14 of 82 counties, a civic group reported, none were registered.

Local white officials told Mr. Lee that if he would stop trying to help other Black citizens vote, he and his wife would be allowed to vote. He politely declined their offer.

He and Mr. Courts received threatening calls. Other Black residents’ windshields were smashed. One rock had a note attached: “You n—-rs…this is just a token of what will happen” for registering. Rosebud Lee beseeched her husband to lower his profile, but “he said somebody had to lead.”

On the night of May 7, 1955, Mr. Lee was driving home from a meeting with Gus Courts when a convertible swerved past. People on the block heard a shotgun’s blast, then a car crash. The shots tore Mr. Lee’s face apart.

The white sheriff claimed the crash killed Mr. Lee. When an autopsy found lead pellets in his face, the sheriff said these might be dental fillings. Finally he theorized that Mr. Lee was a “ladies’ man” who had been shot by a rival. No one was ever charged in Mr. Lee’s murder.

Rosebud Lee—like Emmett Till’s mother, months later—insisted her husband’s casket be open at his funeral. Two thousand people attended. Jet Magazine and the Chicago Defender ran photos of George Lee’s mutilated face.

Six months later, Mr. Courts was wounded by a shotgun blast fired into his store. He survived, moved North, and testified before a Senate subcommittee about how “the blood began to run in Mississippi.”

Gus Courts in critical condition at a hospital in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, after being shot on November 26, 1955. (Library of Congress)

A white legislator’s deadly anger

Herbert Lee, 49, knew the perils he and other Black farmers in the Mississippi Delta faced if they tried to vote. Mr. Lee, who had seven children, had helped found the county NAACP branch in 1953 and by 1961 was helping another civil rights group, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, register voters. There was talk that his efforts had angered a white man he’d known since childhood, state Rep. Eugene H. Hurst Jr.

Louis Allen

A Justice Department lawyer investigating white attacks on civil rights workers was planning to visit Mr. Lee’s farm on his next trip to Mississippi when he heard that Eugene Hurst had shot Mr. Lee to death.

The killing occurred at a cotton gin in Liberty, Mississippi, on September 25, 1961. Mr. Lee had arrived with a truckload of cotton. Witnesses saw Mr. Hurst shoot him.

The legislator claimed he’d been arguing with Mr. Lee over a $500 debt, and that his gun had discharged accidentally when he struck Mr. Lee in self defense. A Black witness, Louis Allen, corroborated this, and an all-white inquest jury swiftly exonerated Mr. Hurst.

Months later, Mr. Allen, a logging operator, admitted he had been pressured to testify falsely. The truth, he told the FBI, was that Eugene Hurst killed Herbert Lee for registering Black voters.

His recanting made Mr. Allen a target of harassment, much of it from the white local sheriff, Daniel Jones. In 1962, Mr. Jones arrested Mr. Allen for “interfering with police business”—a charge the sheriff later admitted was flimsy—and broke his jaw with a metal flashlight.

In 1963, after the sheriff arrested him again, a white businessman warned Mr. Allen: “Louis, the best thing you can do is leave. Your little family, they’re innocent people…All of you could get killed.”

Mr. Allen made plans to move to Milwaukee on February 1, 1964, but the night before, as he arrived home in his logging truck, a white man ambushed him. Mr. Allen dived under his truck but was killed by shotgun blasts. His last stop that day had been to seek a reference letter from a white employer who knew his work. The letter was found in his glove compartment.

Sheriff Daniel Jones spoke to reporters at the scene. Mr. Allen’s son Hank heard the sheriff tell his mother, “If Louis had just shut his mouth, he wouldn’t be layin’ there on the ground.”

In 2006 the FBI reopened the case. Sheriff Jones denied involvement in the murder and cited his Fifth Amendment rights when asked if he was a Klan member.

He died in 2013. Two years later, the FBI closed the case, saying “the most viable theory” implicated him and two other deceased men in Mr. Allen’s murder.

Another NAACP activist, another bomb

Wharlest Jackson, 36, a Korean war veteran and father of five, was treasurer of the NAACP in his hometown, Natchez, Mississippi. In 1967, Armstrong Tire and Rubber Co., where he’d worked for 11 years, promoted him as its first Black employee to become a mixer of chemicals. The promotion came with a raise of 17 cents an hour.

Some of Mr. Jackson’s white coworkers were members of the Ku Klux Klan. Mr. Jackson and his wife Exerlena had helped care for Black coworker and Natchez NAACP president George Metcalfe, after he was disabled in 1965 by a bomb rigged to his car’s ignition.

Wharlest Jackson’s widow, Exerlena Jackson, looks at family photos with her children following her husband’s killing. (AP)

On the night of February 27, 1967, Mr. Jackson was almost home from work when a bomb under the driver’s seat of his pickup truck exploded. Eight-year-old Wharlest Jr. was riding his bicycle nearby and found his father’s mangled body.

While the governor called it “an act of savagery,” investigations ended without prosecutions. Decades later, federal prosecutors who reviewed the case said they still could not “conclusively” identify the killers.

The Battle Goes On

Resistance to Black voting has continued in the 21st century—and not just in the South.

In 2013, the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder effectively gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by striking down the requirement that states with histories of voter discrimination obtain “pre-clearance” from the federal government before changing their voting laws.

States across the country have since enacted voting restrictions and engaged in illegal purges of voting rolls and other voter suppression tactics that, as the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice has said, “fall hardest on communities of color.”

A woman stands outside the U.S. Supreme Court on February 27, 2013, ahead of oral arguments in Shelby County v. Holder. (AP)

Some states disenfranchise people for felony convictions; Mississippi includes offenses such as shoplifting, and disenfranchises a far greater share of Black citizens than white.

The fearless work of Black activists who were murdered led to historic victories in

Congress and the courts. Millions of Black citizens registered, voted, and helped elect the first generation of Black officeholders in the South since Reconstruction—and the first Black president.