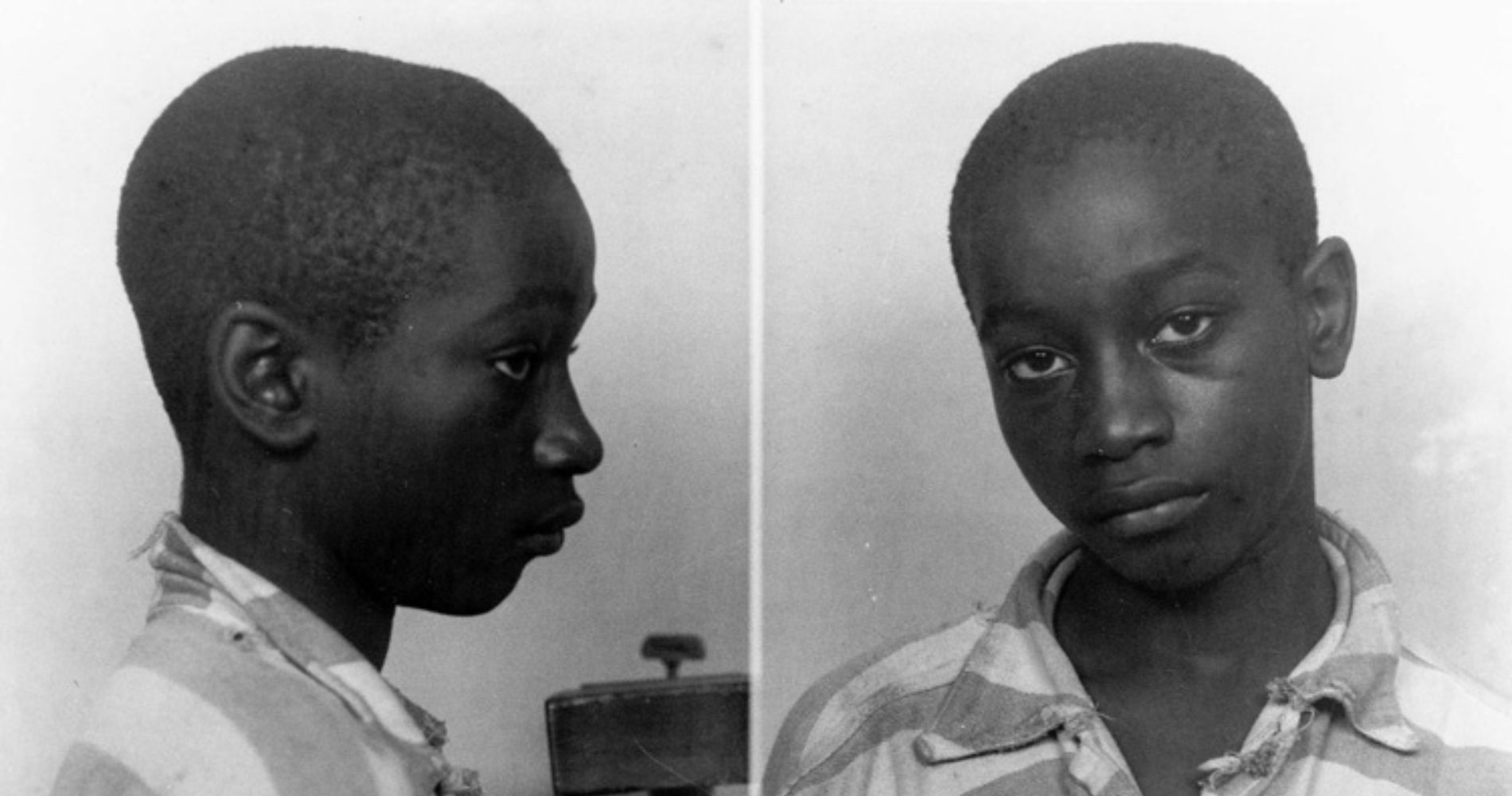

On a spring afternoon in 1944, George Stinney Jr., 14, and his little sister were grazing the family’s cow near railroad tracks that separated Black and white families in Alcolu, South Carolina. Two white girls, ages 11 and 7, stopped by to ask where they could find wildflowers called maypops. When George said he didn’t know, the girls went on their way.

The girls’ bludgeoned bodies were found the next morning. That afternoon, deputy sheriffs came to the Stinney home, handcuffed George, and took him away. They questioned him for hours, without his parents or a lawyer present, and claimed the Black boy had confessed to killing the white girls. No written or oral confession—no evidence of any kind against young George—was produced. George’s father was fired from his job at the sawmill that night. Amid threats of a white mob, the family was forced to flee town.

A month later, in a courtroom overflowing with 1,500 white spectators, George faced a sham trial virtually alone. Black citizens, including his parents, were barred from attending. George’s attorney, a tax commissioner with political ambitions, neither challenged the prosecution nor called any defense witnesses. The trial lasted two hours. The jury—all 12 jurors were white in a county that was almost three-quarters Black—convicted George after deliberating for 10 minutes. The judge sentenced him to death that day. There were no appeals.

And so, on the morning of June 16, 1944, 14-year-old George Stinney Jr. faced his execution alone.

At 90 pounds, he was so small that state officials made him sit on a book—said to be the Bible he carried with him to the death chamber—in order to strap him to the electric chair. Even so, his feet did not reach the floor. As 2,400 volts of electricity surged through his body, according to newspaper accounts, the mask slipped, revealing George’s eyes—wide open and streaming with tears.

He was the youngest person documented to have been executed in the U.S. in the 20th century.

Seventy years later, in 2014, the case was reopened and evidence of George Stinney’s innocence was presented. Circuit Court Judge Carmen T. Mullen vacated the conviction, finding that George Stinney was fundamentally deprived of due process throughout the proceedings against him and that his alleged confession “simply cannot be said to be known and voluntary.” The court also found that George’s court-appointed attorney “did little to nothing” to defend him, writing that the lawyer’s representation was “the essence of being ineffective.” The judge concluded, “I can think of no greater injustice.”

George Stinney’s case was no outlier in American history. The American Law Institute specified in the 1962 Model Penal Code that “civilized societies will not tolerate the spectacle of execution of children.” But in fact, the U.S. tolerated the execution of children until 2005, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark Roper v. Simmons decision banning the juvenile death penalty as a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Court-ordered executions of children were not the only “spectacle” American society tolerated. As EJI has documented, dozens of Black children were lynched in the 20th century. Many of these racial terror lynchings were carried out by mobs of white people in broad daylight. Local, state, and federal officials tolerated—and sometimes encouraged and participated in—these lawless killings, especially by granting impunity to mob participants, who rarely faced criminal prosecutions or any other consequences for their actions.

James Gillespie, believed to be as young as 10, and his brother, Harrison, about 13, were lynched by a mob of white people in Rowan County, North Carolina, in 1902. A 10-year-old girl named Dosia Padgett was lynched along with her father Sam Padgett in Tattnall County, Georgia, in 1907 by 500 armed white men. Willie Howard, 15, was lynched by a mob of white people who forced his father, James Howard, to witness his son’s lynching in Suwannee County, Florida, in January 1944—six months before George Stinney Jr. was executed by the state of South Carolina.

Who Was Executed? Persistent Racial Disparities

Children who were sentenced to death and those who were executed in the U.S. were overwhelmingly poor, Black, male, and residing in Southern states. Legal scholar Victor L. Streib’s landmark 1987 study of American “juvenile executions” found that, in a nation where Black people have never comprised more than 15% of the population, 69% of people executed for crimes committed before they turned 18 were Black.

In 89% of cases ending in executions, the victim was white, according to Mr. Streib’s study, which documented 281 executions of children dating back to colonial times. The majority of child executions were in the South, 91% of 183 people executed for offenses committed before they turned 18 were Black.

Racial disparities in juvenile death penalty cases can also be seen at the state level. Twelve of the 18 children Texas executed between 1859 and 1986 were Black. So were all 17 teenagers executed by Virginia, and all 11 executed by Alabama. Of 41 teenagers Georgia executed between 1848 and 1957 for juvenile crimes, 39 were Black. All 45 juveniles sentenced to death in South Carolina between 1865 and 1972 were Black, according to a 2017 study. Thirty-one—including George Stinney—were executed.

As EJI has reported, two-thirds of the people executed in America in the 1930s were Black. By 1950, African Americans comprised 22% of the South’s population but made up 75% of the people executed there.

The rate of executions slowed by the 1960s as more states abolished the death penalty, and in 1972, the Supreme Court banned the use of the death penalty until new laws were upheld in 1976.

But the racial imbalance in juvenile executions persisted. Of 19 people put to death between 1990 and 2003 for crimes when they were children, 12 were Black or Latino. In 14 of the 19 cases, the victims were white.

In 2005, when the Supreme Court banned the execution of people convicted of crimes as children, the 71 men on death row for crimes committed before age 18 included 47 men of color. The ruling came too late for the 281 people executed in America for crimes that occurred when they were children.

The Death Penalty for Children and Racial Terror Violence

Local officials in Southern states justified their haste to execute Black children as necessary for preventing lynchings. The formation of a lynch mob in Alcolu, South Carolina, had been fueled in part by white officials’ claims that George Stinney Jr. had sexually assaulted one of the white girls, even though he was never charged with assault, and no evidence of assault was found.

Decades after George Stinney’s execution, the self-proclaimed instigator of the mob that had threatened the 14-year-old boy told a historian, “We were gonna lynch him…They made a deal with us: let them try him and they’d guarantee us that we could see him, if he was convicted—they didn’t say he’d be convicted—we could see him if he got the electric chair…[W]e went [to the penitentiary in Columbia] and we seen it happen.”

The mere accusation of sexual impropriety regularly aroused violent mobs and ended in lynching. Accusations of “assault” extended to any action that could be interpreted as a Black person seeking contact with a white woman or girl. These accusations were often based on merely looking at or accidentally bumping into a white woman, smiling, winking, getting too close, or even being disagreeable.

Allegations of sexual impropriety toward a white woman or girl were particularly perilous for Black children. Convictions for such crimes led to 43 court-ordered executions—all of them of Black children.

Some of the Black Children Executed by States

- Joe Persons. While George Stinney is the youngest person documented to be executed in the 20th century, researchers believe Joe Persons was 12 or 13 when he was hanged in Georgia in 1915. He was tried, convicted, sentenced, and executed by Georgia authorities—all within two months—for allegations of sexual impropriety against a white girl. Newspaper accounts said he weighed only 65 pounds and that officials had considered adding weights to his body to make sure he was hanged until death. Georgia Gov. Nathaniel Harris, a Confederate veteran, turned down lawyers’ pleas for a reprieve, saying doctors had determined the boy “had sense enough to know full well what he was doing when he committed the crime.”

- Lonnie Dixon. On May 1, 1927, after a 24-hour-long police interrogation in Little Rock, Arkansas, authorities claimed that Lonnie Dixon, who was Black, confessed to killing an eight-year-old white girl whose body was found in the belfry of the church where Lonnie’s father was the janitor. With a mob of white residents threatening to lynch father and son, police transported them to a jail in Texarkana to await Lonnie’s May 19 trial. On May 4, having stormed the penitentiary outside Little Rock in search of Lonnie, a mob of thousands targeted another Black man, John Carter, who was accused of assaulting a white woman and her daughter. The mob hanged Mr. Carter from a telephone pole, riddled his body with bullets, and dragged his corpse through the streets behind a caravan of cars before setting it ablaze in the center of the Black section of town. White people rioted and looted Black businesses and churches. Lonnie Dixon was executed on June 24, 1927, his 16th birthday.

- Clarence Lowman. At 14, Clarence Lowman was the youngest of three Black cousins convicted in 1925 of killing the white sheriff of Aiken County, South Carolina, as the sheriff and deputies tried to execute a search warrant at the home of the cousins’ relative.The relative’s wife was killed in the gun battle that followed. The state supreme court found that all three convictions were obtained improperly and ordered retrials. A judge directed an acquittal for one of Clarence’s cousins at the end of the first retrial—but that night, a mob of white men dragged all three from their cells and shot them to death. An investigation by the NAACP revealed that the new sheriff was “the leader of the vigilantes and the architect of the lynching,” according to a 2017 study.

- James Lewis Jr. and Charles Trudell. Both 14 years old and Black, James Lewis Jr. and Charles Trudell were alleged to have killed their white boss during a robbery attempt at a Mississippi lumber mill in 1947. Their confessions were coerced and they were tried by an all-white jury. Despite an international outcry, neither President Harry Truman nor Mississippi’s segregationist governor, Fielding Wright, intervened. The teenagers were electrocuted as white spectators cheered outside the prison.

Children Are Different from Adults

In hundreds of ways ranging from mandatory school attendance to harsher penalties for crimes against minors, the law recognizes that children are different from adults.They are more vulnerable, emotional, and impulsive, and more likely to change as they grow up. Laws protect children from their own poor decisions and from adults who would harm them.

But for most of the nation’s history, no such laws protected children convicted of capital crimes. The juvenile death penalty reached its peak in the 1940s, when 53 people were executed for crimes when they were children. In that era, white Southern politicians demonized Black children accused of crimes as animals who did not deserve to live. Newspapers further inflamed fears by unjustly stereotyping Black children as “young brutes.”

In 1920, when Mack Thompson, 14, was charged with “assault with intent to ravish” two white girls, ages 10 and 12, in Lexington County, South Carolina, the headline in the Charlotte News read: “Negro Boy charged with Usual Crime.”False stereotypes and presumptions of guilt have endangered the lives of Black children for generations. In the 1990s, death sentences for children reflected attitudes of elected officials wanting to appear tough on crime as they stoked fears of a new generation of so-called young Black “super predators” that never existed. Juveniles were treated as adults in the courts even as crime rates began to decline.

Reckoning with the Tragedy of George Stinney 70 Years Later

Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, were reported missing on the evening of March 23, 1944, hours after they’d set out to look for maypops. Hundreds of residents joined the search, including George Stinney, a former sharecropper, and his son, George Jr., who mentioned that he had seen the girls that afternoon.

One month later, George Stinney Jr. stood trial inside the Clarendon County courthouse, where a statue of a Confederate soldier towered out front. Among those who had been barred from the courtroom for being Black were George’s siblings, Amie, 8, Clarence, 12, and Kathleen, 10. They had all been with George on the day of the killings and might have testified in his defense. But George’s attorney, Charles Plowden, who would go on to be elected to the state legislature, had never interviewed his siblings.

South Carolina politics were in turmoil that spring over a Supreme Court ruling outlawing Southern states’ all-white primaries. Ten days before trial, Gov. Olin Johnston reassured legislators that he would “keep our white Democratic primaries pure and unadulterated.” Disenfranchising Black voters ensured all-white juries, since jurors were chosen from voter rolls.

As the execution date neared, Black advocacy groups and soldiers writing from the battlefields of World War II implored the governor to intervene. “CHILD EXECUTION IS ONLY FOR HITLER,” one telegram said. Though autopsies showed no evidence of rape, and no rape was charged, the governor—who was running for a Senate seat against a virulently segregationist incumbent and couldn’t afford to be “soft” on race —wrote in one reply that George had “killed the larger girl and raped her dead body.”

Months later, Olin Johnston won his Senate race, and served there until his death in 1965.

In June 2014, Stinney family supporters erected a memorial marker near Alcolu.

In June 2014, Stinney family supporters erected a memorial marker near Alcolu.Seventy years after George’s execution, his surviving siblings finally got the chance to testify on his behalf. At a 2014 hearing, Amie Stinney Ruffner, 77, said she had been with her brother when the two girls stopped to ask about maypops. Kathleen Stinney Robinson, 79, and Charles Stinney, 78, in frail health and testifying via video, said George was home all the rest of that afternoon.

“I wish that I could have come forward much sooner,” Charles Stinney said. “George’s conviction and execution were something that my family believed could happen to any of us…Therefore, we made a decision for the safety of the family to leave it be.” He and his siblings all eventually moved North.

“I never heard my mother laugh again,” Amie Ruffner told an interviewer years later.

By Sara Rimer and Dan Biddle, EJI Senior Writers