Very little has been done to acknowledge the thousands of Black veterans in the United States who were abused, attacked, or killed in this country because of their status as military veterans.

Inspired to defend their country and pursue greater opportunity, African Americans have served in the U.S. military for generations. But for over a century, instead of being treated as honored members of society upon their return from military service, Black veterans were accosted, attacked, or lynched. EJI has documented at least 35 military veterans who were victims of racial terror lynching from 1865 to 1950.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, white supremacy and racial hierarchy remained law and custom throughout the nation. Many white people feared that Black soldiers who had experienced the pride of military service would resist the disenfranchisement, segregation, and second-class citizenship that still characterized the African American experience.

In August 1917, U.S. Senator James Vardaman of Mississippi warned that, once a Black soldier was allowed to see himself as an American hero, it would be “but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected.” Bringing Black soldiers home to the South with expectations of equality, he predicted, would “inevitably lead to disaster.”

For Senator Vardaman, Black soldiers’ potential as community leaders was terrifying, and the “disaster” would be a mass movement for African American rights. Indeed, many African American veterans were determined to fight for their own freedom and equality, and veterans like Hosea Williams and Medgar Evers played central roles in what became the civil rights movement. The effort to suppress that potential leadership made Black veterans targets, and many suffered brutal violence for protesting mistreatment or simply wearing their military uniforms.

In August 1898, a Black Army private named James Neely was shot to death by a mob of white men in Hampton, Georgia, for protesting a white storekeeper’s refusal to serve him at the soda counter.

In Hickman, Kentucky, a recently-discharged Black soldier named Charles Lewis was lynched in uniform in December 1918, just weeks after the end of World War I. Mr. Lewis was standing on the street when a white police officer began harassing him and claimed he fit the description of a robbery suspect. When Mr. Lewis insisted that he was a soldier with no reason to rob anyone, the officer accused him of assault and arrested him. The next morning, a mob of white men broke into the jail, seized Mr. Lewis, and hanged him.

Black veterans of World War II also faced violence for the most basic assertions of equality and freedom. In August 1944, the white owner of a small restaurant in Shreveport, Louisiana, shot and wounded four Black soldiers he claimed “attempted to take over his place.” The white assailant faced no charges.

In June 1947, a Black Navy veteran and Temple University student named Joe Nathan Roberts was visiting family in Sardis, Georgia, when a group of white men became upset because he refused to call them “sir.” Later that night, the men abducted Mr. Roberts from his parents’ home and lynched him.

For Black people, being a military veteran made them a target and put them at greater risk of violence and menace as a result of racial prejudice and hierarchy. The refusal of federal officials or the U.S. military to intervene and provide needed protection and assistance made the trauma of this history all the more painful to Black veterans.

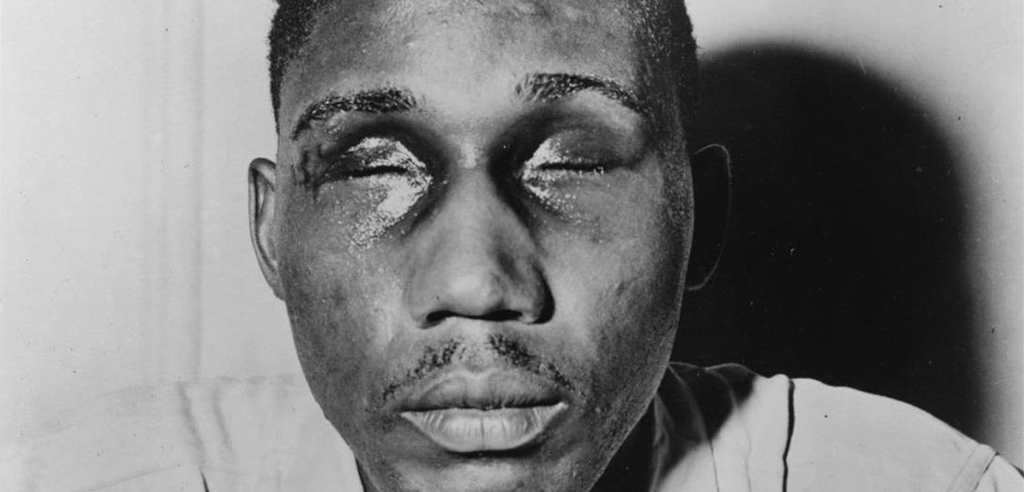

Sgt. Isaac Woodard was beaten so badly by South Carolina police that he was permanently blinded.

On September 9, 1948, a group of white men shot and killed a 28-year-old Black veteran named Isaiah Nixon outside of his home and in front of his wife and six children, just hours after he defied threats and voted in the local primary election in Montgomery County, Georgia. Two white men arrested and charged with his death were later acquitted by all-white juries.

These and countless more Black veterans served bravely in defense of America only to face terrible violence, lynching, and abusive mistreatment when they returned.

In November 1942, while stationed at Camp Polk, Louisiana, Private Merle Monroe wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier describing the Black soldier’s struggle to maintain a sense of patriotic pride in the face of lynching. “Paradoxically enough,” he wrote, “our country spends millions annually in effort to build up Negro morale, both in and out of the army, yet, foolishly, destroys the blue print of its program by tolerating brutal killings without even a pretense of a fair trial.”

Very little has been done to acknowledge the thousands of Black veterans who were abused, attacked, and killed in this country because of their status as military veterans.

This year, as we observe Veterans Day amid ongoing national debates about racial inequality, police brutality, protest, and patriotism, EJI honors the long tradition of African American veterans who have struggled and died in a dual battle: fighting abroad in defense of country and fighting at home to make that country a place worth defending. Nearly 80 years after they were first published, Private Monroe’s words still ring with a hopeful truth:

Morale to the Negro, as with every human being, is like yeast to bread. Morale puffs us up with love and pride for our country. It puffs us up with the will to fight; to resist any change by force to our way of life. Morale, in a broad sense, is knowledge and understanding of, and faith in the high principles our country must represent: The right to live our lives unhampered by strings of prejudice; the right to earn bread; a place in the sun for us and our posterity. And with these necessary stimulants, we Negro soldiers will resist, with every inch of our stature, any threat to our country’s laws; laws that must protect our rights during periods of tranquility.