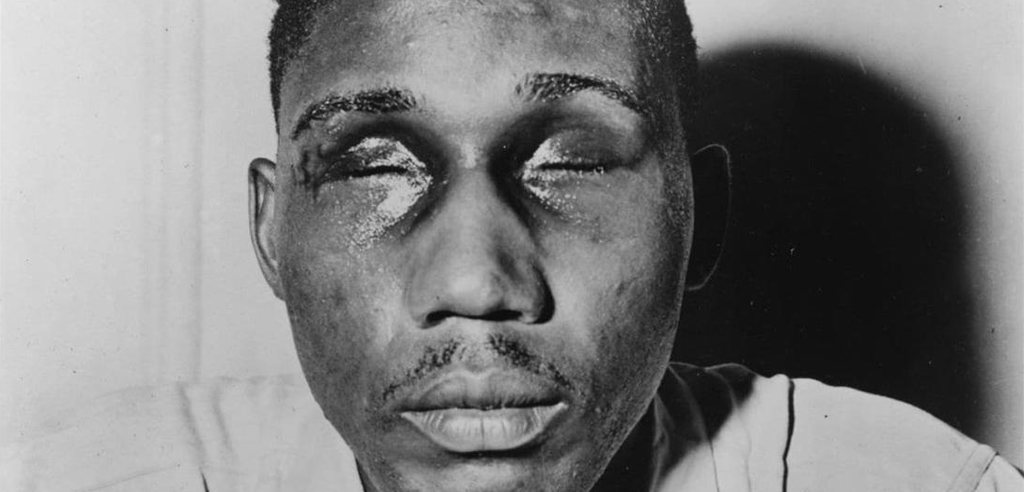

On February 12, 1946, Black World War II veteran Sgt. Isaac Woodard wore his uniform on a bus trip from Georgia to North Carolina. When he protested mistreatment by the white bus driver, South Carolina police beat him so severely he was permanently blinded. The NAACP and others decried the attack, but no one was convicted. On Saturday, February 9, 2019, a historical marker was dedicated in Batesburg-Leesville to acknowledge the attack and its legacy.

For generations of African Americans living under segregation and racial terror in the century after emancipation, military service seemed a chance to earn equality. But between the end of Reconstruction and the years following World War II, thousands of Black veterans were accosted, assaulted, attacked, and killed due to their race. For many, merely wearing a uniform created an immediate risk of attack.

“Negro veterans that fought in this war . . . don’t realize that the real battle has just begun in America,” Sgt. Woodard later said. “They went overseas and did their duty and now they’re home and have to fight another struggle that I think outweighs the war.”

While the nation purported to fight for freedom and democracy abroad, Americans condoned racial terror and Jim Crow segregation that targeted the Black community, including service members. Civil rights activist Hosea Williams, who was captured by the German army during World War II, drew a striking comparison: “I want to tell you the Germans never were as inhumane as the state troopers of Alabama.”

The Blinding of Isaac Woodard

On February 12, 1946, Sgt. Isaac Woodard, 26, a decorated veteran who was honorably discharged from the Army after serving in the Philippines, boarded a Greyhound bus in Georgia, headed home to his wife in North Carolina. When the bus stopped just outside of Augusta, South Carolina, Mr. Woodard asked the driver if there was time to use the restroom, and the driver cursed at him. After a brief argument, Mr. Woodard returned to his seat. At the next stop in Batesburg, South Carolina, the angry driver told Mr. Woodward to exit the bus, where the local chief of police, Lynwood Shull, and several other police officers were waiting. They ordered Mr. Woodard off the bus.

He was beaten at various points while in police custody, despite protesting that he had done nothing to warrant the assault. Chief Shull jammed the ends of his Blackjack into Mr. Woodard’s eyes, at one point striking him so violently that the stick broke.

Mr. Woodard was arrested for drunken and disorderly conduct. The next morning, a local judge fined him $50 and denied his request for medical attention. By the time of his release days later, Mr. Woodard did not know who or where he was. His family found him three weeks later in a hospital in Aiken, South Carolina, after reporting him missing.

By the mid-20th century, violent racialized attacks on Black veterans were slightly more likely to result in investigations and charges against the white perpetrators, but they rarely led to convictions or punishment, even when guilt was undisputed. Under pressure from the NAACP, the federal government eventually charged Chief Shull for the attack on Mr. Woodard, but the prosecution was half-hearted at best. The United States Attorney did not interview any witnesses except the bus driver.

At trial, Shull admitted that he had blinded Mr. Woodard, but Shull’s lawyer shouted racial slurs at Mr. Woodard and told the all-white jury, “[I]f you rule against Shull, then let this South Carolina secede again.” After deliberating for 30 minutes, the jury acquitted Shull of any wrongdoing, and the courtroom broke into applause. Remarking on the outcome, Mr. Woodard said, “The Right One hasn’t tried him yet. . . . I’m not mad at anybody. . . . I just feel bad. That’s all. I just feel bad.”

Mr. Woodard eventually went to New York, where his family cared for him until he died in 1992 at age 73. His nephew, Robert Young, 81, told Stars and Stripes that he rarely spoke about the incident.

Acknowledging Racial Violence Against Black Veterans

The historical marker to honor Mr. Woodard was the brainchild of Don North, a former Army major from Carrollton, Georgia, who spent three years researching and raising money for the marker, the New York Times reports. Most of the marker’s cost was funded by the Disabled American Veterans organization.

Members of Sgt. Woodard’s family and about 80 guests, including United States Representative Joe Wilson and Brig. Gen. Milford H. Beagle Jr., gathered on Saturday for a private ceremony, where officials heard about the lasting impact of the attack on the town and on the Woodard family. Stars and Stripes reported that officials in attendance agreed that it was important for towns like Batesburg-Leesville to acknowledge their history of racial injustice.

State Rep. Jerry Govan of Orangeburg said it’s important for people to accept and acknowledge these moments in history in order to learn and not make the same mistakes of the past.

After the private ceremony, family members, town and civic leaders, and groups of veterans walked the two blocks from the bus stop to the vacant lot where the old jail once stood. There, at the place where Mr. Woodard was beaten and blinded, they unveiled the historical marker, which says the “incident led President Harry Truman to form a Council on Civil Rights and issue Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the U.S. Armed Forces in 1948.”

Batesburg-Leesville Mayor Lancer Shull, who is not related to the former police chief, told Stars and Stripes that the dedication should inspire other towns to have a conversation about the racism that is deeply entrenched in our history. “This should be an inspiration to pull those rugs out and sweep up what has been under there for years,” he said.

“This event had been mostly swept under the rug,” Mayor Shull told the New York Times. “I know it can’t be corrected, we can’t erase what happened but we can acknowledge this horrible incident.”

Frostburg State University professor Andrew Duncan grew up in the town and said he never expected to see anything like Saturday’s dedication. “This sort of reconciliation needs to happen in a lot of places,” he said.