The Oregon Remembrance Project and the Coos History Museum partnered with EJI to erect a historical marker on June 19 in memory of the 1903 lynching of Alonzo Tucker. Mr. Tucker is one of more than 300 documented Black victims of racial terror lynching in non-Southern states and currently the only documented victim in Oregon between 1877 and 1950.

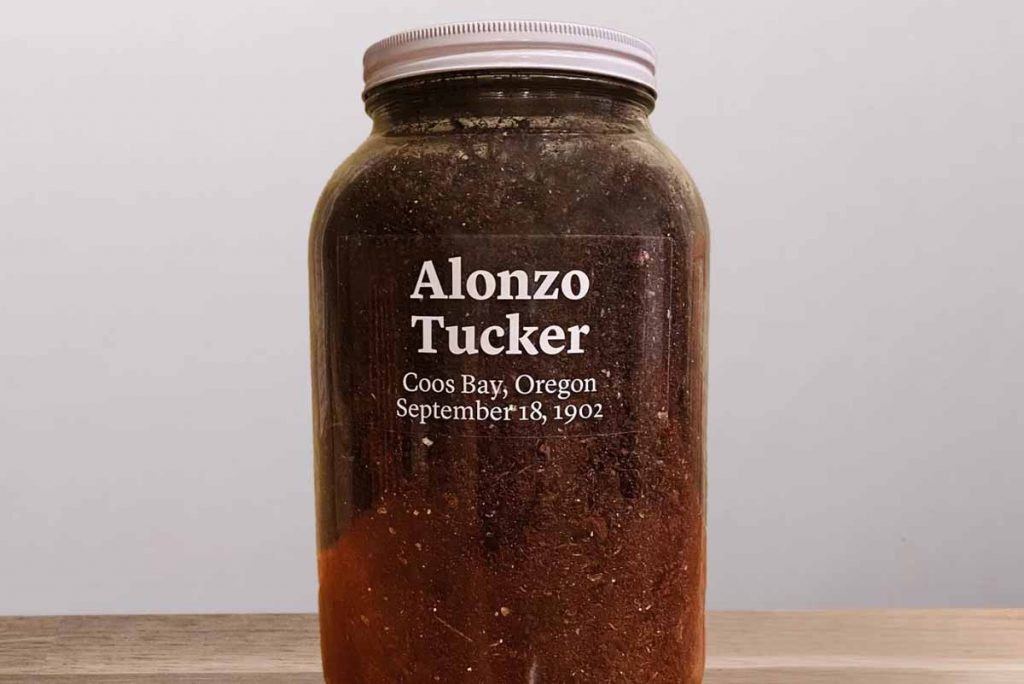

In February 2020, the coalition held a soil collection ceremony and created a permanent exhibit at the Coos History Museum with the jar containing the soil from the site of Mr. Tucker’s lynching.

On June 19, residents from throughout Oregon, including educators, students, faith leaders, public officials, and other community members, gathered in the small town of Coos Bay to dedicate the historical marker as part of the inaugural Juneteenth celebration hosted by the museum.

Marcia Hart, Executive Director of the Coos History Museum, opened the ceremony with approximately 250 people attending in person and approximately 350 attending virtually on the livestream.

During the ceremony, Zachary Stocks, Executive Director of Oregon Black Pioneers, described how Oregon’s constitution originally prevented Black people from residing in the state, leaving the Black population at less than one percent by the time Alonzo Tucker was lynched. “There was no justice for people who looked like him, here,” Mr. Stocks said.

Taylor Stewart, convener of the Oregon Remembrance Project, emphasized the relationship between racial terror lynchings and the death penalty today. “I don’t believe we can truly find reconciliation for this lynching while a disproportionate number of African Americans sit on Oregon’s death row, ” he said.

Other speakers included Coos Bay Mayor Joe Benetti and North Bend Mayor Jessica Engelke, Bishop Laurie Larson Caesar of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, Adian Anselmo and Diamond Tschida from the Black Student Union of Southwestern Oregon Community College, and Heather Coleman-Cox of Juneteenth Oregon. Coalition members also read remarks from U.S. Senators Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden as well as U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio, who were not able to attend the ceremony.

The Oregon Remembrance Project plans to continue remembrance work regarding Oregon’s history of racial injustice and its impact on present-day racial demographics and dynamics throughout the state.

Lynching of Alonzo Tucker

On September 18, 1902, a white mob lynched Alonzo Tucker, a Black man in Coos Bay, then called Marshfield. The day prior, Mr. Tucker had been arrested and placed in jail after being accused of assaulting a white woman near the 7th Street Marshfield Bridge. As news of his arrest spread, a white lynch mob formed. In this era, accusations of Black-on-white assault required no evidence to arouse mobs, and Black men could be lynched for merely interacting with white women, even in consensual relationships.

Mr. Tucker fled and spent the night hiding under docks by the bay as the armed mob searched for him. The next day, Mr. Tucker was found and shot twice. The mob put a noose around his neck and carried him to the site of the alleged assault, but Mr. Tucker died from his wounds on the way. The unmasked mob hanged his body from a light pole on the bridge in broad daylight before 300 spectators. His body remained hanging for several hours, prompting Black families to flee Coos Bay.

Though racial hostility and lynching were prevalent in the South, Oregon was no exception to the anti-Black racism that fueled this era. Founded with a state constitution that banned all Black people by law until 1926, Oregon accommodated mob violence against Mr. Tucker, and no one was held accountable for his lynching.

The Oregon Remembrance Project Coalition

The Oregon Remembrance Project formed in 2018 after Taylor Stewart, then a college student at the University of Portland, visited the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice as part of an immersion program. After learning about the lynching of Alonzo Tucker as well as the relationship between racial terror lynching and the death penalty, a core group of organizers including the Oregon Remembrance Project, the Coos History Museum, and the City of Coos Bay decided to take steps to memorialize Alonzo Tucker’s lynching.

On February 29, 2020, this core group collected soil from the site of Mr. Tucker’s lynching and held a community remembrance ceremony where they dedicated the soil jar, which is now on display in an exhibit at the Coos History Museum. Through the Covid-19 pandemic, the group continued coalition building and decided to work towards erecting a historical marker outside the Coos History Museum to memorialize Alonzo Tucker. The Oregon Remembrance Project is committed to unearthing stories of injustice and undergoing the truth telling work necessary to reconcile historical harms and to understand present-day injustice.

/

Community members gather outside the Coos History Museum on June 19, 2021, for a marker dedication ceremony honoring Alonzo Tucker.

David Rupkalvis

/

The marker memorializing Alonzo Tucker, who was lynched in Coos Bay in 1902, is erected.

/

A jar containing soil collected at the site where Alonzo Tucker was lynched sits at an exhibit inside the Coos History Museum in Oregon.

Lynching in America

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. After slavery ended, many white people remained committed to racial hierarchy and used lethal violence and terror against Black communities to maintain a racial, economic, and social order that oppressed and marginalized Black people. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and created a legacy of injustice that can still be felt today.

Of the hundreds of Black people lynched under accusation of alleged crimes, nearly every one was brutally killed without being legally convicted of any offense. Many African Americans were lynched for perceived violations of social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or being accused of crimes even when there was no evidence tying the accused to any offense. White mobs regularly displayed complete disregard for the legal system, seizing their victims from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or from police custody without fear of legal repercussions for the lynchings that followed. In this environment of official indifference, racial terror remained systematic, far reaching, and devastating to the Black community for generations.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. The narrative historical marker in Coos Bay is among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI to date.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.