EJI partnered with community coalitions in Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Virginia to install historical markers in recent weeks that tell the stories of local racial terror lynchings.

Between 1865 to 1950, thousands of African Americans were victims of mob violence and lynching across the country. Lynching emerged after the Civil War as the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism, intended to intimidate Black people and reinforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Many African Americans were lynched for exercising economic freedoms, perceived violations of social customs, and accusations of crimes. Accusations against Black men by white women regularly aroused mob violence and lynching. A white person’s allegation against a Black person was rarely subject to scrutiny and often sparked violent reprisal, even when there was no evidence tying the accused to any offense.

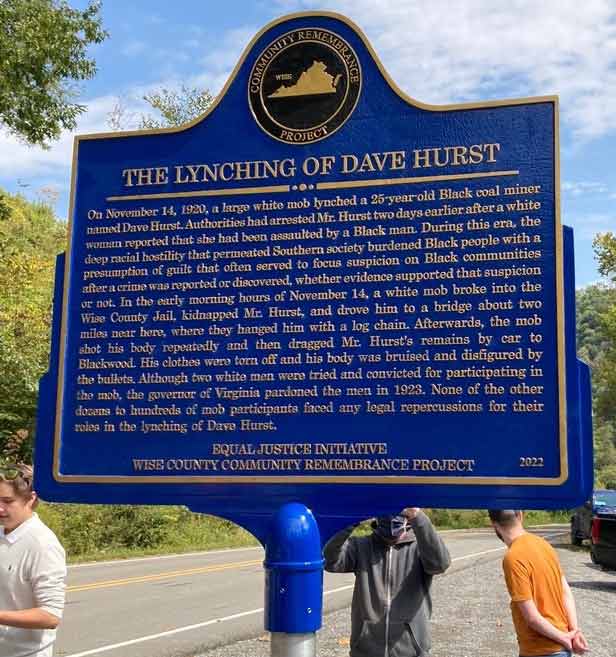

Wise County, Virginia

Dozens of people gathered on September 24 to unveil a historical marker memorializing the 1920 racial terror lynching of 25-year-old Dave Hurst. Located along Kent Junction Road in Wise County, Virginia, the marker was installed by the Wise County/City of Norton Remembrance Coalition working in tandem with EJI.

“Why do we do this?” the coalition’s Preston Mitchell said before the unveiling. “Because we must reveal before we can heal … we are revealing to the community what happened here 102 years ago.”

The Lynching of Dave Hurst

On November 14, 1920, a large white mob lynched a 25-year-old Black coal miner named Dave Hurst. Authorities had arrested Mr. Hurst two days earlier after a white woman reported that she had been assaulted by a Black man.

During this era, the deep racial hostility that permeated Southern society burdened Black people with a presumption of guilt that often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was reported or discovered, whether evidence supported that suspicion or not.

In the early morning hours of November 14, a white mob broke into the Wise County Jail, kidnapped Mr. Hurst, and drove him to a bridge about two miles near here, where they hanged him with a log chain. Afterwards, the mob shot his body repeatedly and then dragged Mr. Hurst’s remains by car to Blackwood. His clothes were torn off and his body was bruised and disfigured by the bullets.

Although two white men were tried and convicted for participating in the mob, the governor of Virginia pardoned the men in 1923. None of the other dozens to hundreds of mob participants faced any legal repercussions for their roles in the lynching of Dave Hurst.

Tom Costa, a history professor at the University of Virginia at Wise, told the TimesNews that public officials from Norton, Wise County, and the state supported the effort to install the marker remembering Mr. Hurst after the Virginia General Assembly passed a resolution in 2019 recognizing the state’s history of racial terror lynching and its legacy.

More than 84 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Virginia, including at least three victims in Wise County.

Fulton County, Georgia

EJI partnered with the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition to unveil four historical markers in Fulton County last month. Two markers memorialize lynching victims in East Point, Georgia, and two tell the story of the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre and its impact on the prosperous Black suburb of Brownsville.

The City of East Point’s Public Art Division joined the coalition and EJI in organizing a dedication ceremony for a new historical marker at 2847 Main Street in the heart of East Point on September 4, the 133rd anniversary of the lynching of 14-year-old Warren Powell.

The Lynching of Warren Powell

On September 4, 1889, a white girl reported being assaulted by a Black male. White men in the East Point area soon began “hunting” for the alleged assailant. They seized 14-year-old Warren Powell and carried him to the local bailiff, who placed him in a jail cell secured by a single padlock.

The mob lingered at the jail and gradually grew in size as others began to congregate. Around 10:00 pm, 15 to 20 masked white men forced their way to the jail door. The men used a hatchet to break down the door and seize Warren. Warren’s tearful parents, who had bravely come to the jail, begged for their son’s life, but to no effect.

Community members look at a quilt made by Remembrance Quilters artist Robin Black in memory of Warren Powell.

Sam Bermas-Dawes/GPB NewsThe mob dragged Warren screaming and pleading across several fields until they reached an oak tree. The mob hanged him there and then returned to the jail, unmasked. A search was later made for his body, which was found the next morning.

After the lynching, white men spread rumors that Black East Point residents were planning to retaliate. Using the rumors as justification, white mobs dragged numerous Black men, women, and children out of their homes and attacked them. Though a reward of $100 was offered for the arrest of the mob perpetrators, no evidence indicates that anyone involved in the racial terrorism in East Point was held accountable.

On September 24, dozens gathered in Sumner Park, where Zeb Long was lynched 116 years earlier, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reports.

The Lynching of Zeb Long

On the morning of September 24, 1906, the body of a 30-year-old Black man named Zeb Long was found hanging from a tree in East Point.

Two days earlier, a mob of at least 5,000 white men and boys began terrorizing and violently attacking Black men, women, and children in the Atlanta area, inciting the four-day 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre. Law enforcement failed to intervene until the governor ordered state troops to regain control of the city.

As police roamed East Point on the evening of September 23, they encountered Mr. Long and arrested him for “incendiary talk about the way white people were treating negroes.” The officers took Mr. Long to the small, wooden jail in East Point that was described by a local newspaper as a “flimsy” shack.

The arresting officer took no further precautions, and around 5 am on September 24, a mob of at least 50 white men stormed the jail and kidnapped Mr. Long. Placing a rope around his neck, the mob dragged Mr. Long to a wooded area about half a mile west of the jail. Though Mr. Long “begged for his life,” the mob “promptly” lynched him and left his body hanging from a tree.

A coroner’s jury determined on September 25 that Mr. Long had been killed by “unknown parties,” and no further investigation was made. No one who participated in the white mob violence that terrorized the East Point Black community and lynched Mr. Long between September 22 to 25 was held accountable for their crimes.

At least 36 Black people were victims of racial terror lynching in Fulton County between 1865 and 1950, and at least 595 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Georgia during that time.

The Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906

The racial terror lynching of Mr. Long and the racial violence in East Point took place during the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906. Ann Hill-Bond, co-chair of the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition, said at Mr. Long’s marker unveiling that while terror was reigning in Atlanta, “The East Point mob realized that it was open season on African Americans and took part in it.”

A quilt on display during the marker dedication ceremony honoring Zeb Long depicts the violence of the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre.

Christina Matacotta/Atlanta Journal-ConstitutionMr. Long was one of at least 12 Black people who were lynched before midnight on September 22, 1906, when white mob violence erupted in Atlanta. Thousands of white men and boys gathered in downtown Atlanta screaming, “Get them all! Kill the Negroes!” Over four days, white mobs terrorized Black people in Atlanta’s Five Points area and nearby Black neighborhoods, burning homes, destroying Black-owned businesses, and attacking any Black person in their path.

Reports indicate that hundreds of Black people filled Grady Hospital’s segregated ward for medical treatment before the violence ended on September 25. At least 25 Black men and women were lynched in the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre.

Months prior, racist gubernatorial campaigning and sensational news reporting about alleged assaults against white women by Black men had deepened racial animosity in white communities against Black Georgians.

When white mob violence erupted on September 22, law enforcement failed to intervene. Left to defend themselves, one Black neighborhood on present-day John Wesley Dobbs Avenue successfully repelled an attack by turning out the streetlights and firing on the mob.

On the 24th, Black Atlantans in Brownsville stopped a mob attack on their neighborhood, but county police arrested them and left them in streetcars that were attacked by white mobs. At least one of the Black people detained was killed. Of the thousands of white mob participants, only two were ever convicted for their role in the massacre.

Brownsville

After the September 24 marker unveiling in East Point, Ms. Hill-Bond dedicated a marker in nearby Brownsville, a thriving suburb of Atlanta where Black people overcame enormous obstacles to pursue land ownership, civic engagement, leadership roles, and educational opportunities.

In 1887, Clark College established the South Atlanta Land Improvement Company to develop 50 acres adjacent to the college as the premier Black suburb of Brownsville, which emerged as a middle and upper-class neighborhood.

In response to the progress of Black people during and post-Reconstruction, state and local legislatures enacted racially discriminatory statutes and ordinances known as “Jim Crow” laws. This codified system of racial apartheid restricted Black economic and civil rights, mandating segregation of schools, public spaces, and other institutions.

Legally barred from many parts of Atlanta, Black people spent their money in Brownsville, creating a self-sustained economy and community that numbered 2,000 people by 1904. As Brownsville prospered, it became a place of higher education, performing arts, and community development.

But Brownsville’s success was met with resentment from white Atlantans, and in 1906, white mobs attacked the community during the Atlanta Race Massacre. Although Jim Crow laws prohibited Black people from possessing firearms, Brownsville residents armed themselves to protect their homes, businesses, and schools. When the mobs stormed Brownsville on September 24, residents fought back, resulting in the death of a white police officer.

The mob continued to terrorize Brownsville with impunity, but nearly 60 Brownsville residents were arrested and sentenced to life for the officer’s death. After the attacks, journalist Ray S. Baker wrote of Brownsville’s resilience, noting that “practically every” resident had preserved their homes, despite the failure of white officials to provide support after the massacre.

Chatham County, North Carolina

On September 24, community members and local and state officials gathered in Pittsboro, North Carolina, to unveil a marker commemorating six people—Jerry and Harriet Finch, John Pattishall, Lee Tyson, Henry Jones, and Eugene Daniel—who were lynched in Chatham County between 1885 and 1921.

EJI partnered with the Community Remembrance Coalition Chatham, the NAACP, and other community groups to install the marker, which is located outside the Chatham County Government Annex.

The dedication ceremony featured poetry, speakers, dance performances, and music. Chatham County Sheriff Mike Roberson opened the event. “I encourage all of you to be part of the ongoing improvement of our future together,” he said. “We cannot have reconciliation without justice. We cannot have justice without truth. We cannot have truth without trust.”

Community members in Chatham County unveil the new historical marker commemorating six victims of racial terror violence.

Chatham CountyLynching in Chatham County

Between 1885 and 1921, white mobs terrorized and lynched at least six Black people in Chatham County, creating a legacy of violence, intimidation, and injustice.

On September 28, 1885, a white mob in Pittsboro lynched four Black people—Jerry Finch and his wife, Harriet, John Pattishall, and Lee Tyson—following the unsolved murders of two white families. After months of terrorizing them, the mob stormed the jail, seized them, and hanged them from a tree despite their pleas of innocence.

After the lynching, newspapers reported the lack of evidence against all of the victims for crimes that the mob accused them of committing, and the Chatham Record concluded, “If one set of men can force open our jail for one purpose,…who will be the next victim, and whose life is safe?”

Fourteen years later, a white mob lynched a Black farmer in his mid-thirties named Henry Jones on January 11, 1899. The mob targeted Mr. Jones merely because he lived near a white woman who was found dead the night before.

Then, on September 18, 1921, a white mob lynched a 16-year-old Black boy named Eugene Daniel after he was falsely accused of assaulting a white girl. The mob took Eugene five miles east to an area near Moore’s bridge, hanged him with a chain, and shot his body repeatedly.

The next day, at least 1,000 spectators came to view Eugene’s hanged remains.

No mob participants were held accountable for lynching these Black men, women, and children.

Cameron Sanders, the great-great-great-nephew of Eugene Daniel, speaking during the marker dedication ceremony.

Nikki Witt/Chatham News+RecordAt the marker dedication, Cameron Sanders, the great-great-great-nephew of Eugene Daniel, read a letter to his ancestor.

“Dear Uncle Eugene,” he began, “My name is Cameron Wesley Sanders, and I am your great-great-great-nephew. My great great grandmother is your older sister. And I am the great-grandson of her sixth born son Maynard. I called him Pop-pop. Unfortunately, you did not get to meet him because he was born in 1923, two years after you were lynched by neighbors in our community.”

Karen Howard, chair of the Chatham County Board of Commissioners, accepted the marker on behalf of the county. “The families whose loved ones were murdered and the extended community that continued to live in the shadow of the terror of lynchings now have a remembrance of those lives and a public acknowledgment of the many failures of the system and the injustice that took them away,” she said at the dedication ceremony.

Although many victims of racial terror lynching will never be known, at least 120 lynchings have been documented in North Carolina, with at least six known to have taken place in Chatham County, between 1865 and 1950.

Tulsa, Oklahoma

On September 13, EJI partnered with the Terence Crutcher Foundation, Oklahoma State University at Tulsa, and the Tulsa Community Remembrance Coalition to unveil and dedicate a historical marker at the intersection of Greenwood Avenue and John Hope Franklin Boulevard on the OSU-Tulsa campus. The marker commemorates the founding of the Greenwood District in 1906.

The dedication ceremony was part of a weeklong series of events to honor Terence Crutcher, who was killed by a police officer during a traffic stop in north Tulsa six years ago.

“We bear witness to the past. We honor the power of the present. And we vow to not betray the future. We shall not forget,” Dr. Tiffany Crutcher, Terence’s twin sister and founder of the Terence Crutcher Foundation, said at the unveiling.

Tiffany Crutcher and Shirley Barnett hug after the marker dedication ceremony commemorating the history of the Greenwood District. The new historical marker was erected by the Terence Crutcher Foundation, the Tulsa Community Remembrance Coalition, and Oklahoma State University-Tulsa in partnership with EJI.

Mike Simons/Tulsa WorldThe Greenwood District

Founded in 1906, Tulsa’s Greenwood District was one of many Black communities created to welcome African Americans seeking freedom and opportunity in Oklahoma after suffering generations of slavery elsewhere. In 1889, O.W. Gurley, a wealthy Black man from Arkansas, purchased over 40 acres of land and sold it to Black people relocating to the area.

Following Reconstruction and the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, state legislatures enacted racially discriminatory statutes and ordinances known as “Jim Crow” laws. This codified system of racial apartheid restricted the economic and civil rights of African Americans and affected almost every aspect of daily life, mandating segregation of schools, parks, restaurants and other private and public institutions.

Legally barred from white businesses, Black people spent their money in Greenwood creating a self-sustained economy. By 1920, Greenwood boasted dozens of Black-owned businesses and an educational system for Black students. J.B. Stafford built and operated a luxury hotel that became the largest Black-owned hotel in the country.

Simon Berry ran transportation services including a chartered plane service. John and Loula Williams owned a theater in addition to several other businesses. A.J. Smitherman founded the Tulsa Star, a key resource in documenting the community’s events. Dr. A.C. Jackson, a prominent Black surgeon, treated both Black and white patients.

Black visionaries determined to overcome racial oppression joined and built what would come to be known as the epicenter of wealth and enterprise in Black America. But Greenwood’s prosperity was met with consistent resentment from Tulsa’s white community.

In 1910, the city of Tulsa annexed Greenwood, but denied Black residents access to basic services. Tulsa also experienced exponential growth driven by oil profits, and white developers grew frustrated about being unable to access the Black-owned land in Greenwood.

Despite the devastation and tremendous loss of life during the 1921 Tulsa massacre, Greenwood’s surviving residents rebuilt the community. The Greenwood District reached its economic peak in the 1930s and 40s, bringing back Black-owned businesses and Black medical providers to the area.

By 1950, Greenwood boasted even more amenities than before the massacre, earning its popular title ‘Black Wall Street.’ Urban Renewal projects in the 1960s and 70s, such as Interstate Highway 244, seized and demolished much of Greenwood’s commercial property. The legacy of resilience is still evident in Greenwood today.