For much of the summer and early fall of last year, as the State of Missouri prepared to kill him, Marcellus Williams was a topic of national news. Mr. Williams had maintained his innocence throughout more than 20 years on death row for the 1998 murder of a white woman named Felicia Gayle; now, a media spotlight shone upon a unique collection of allies including prosecutors, jurors, and journalists working to save his life.

Legal briefs and newspaper headlines emphasized arguments over improperly withheld evidence, recanted witness testimony, DNA testing, and the morality of capital punishment. But one question received comparably little attention: were Black jurors systematically excluded from hearing the case?

The State of Missouri executed Marcellus Williams on September 24, 2024.

At the 2001 trial, State prosecutors rejected six of the seven eligible Black jurors—including one young man prosecutors did not want on the jury because he and Mr. Williams “looked like they could be brothers.” As a result, Mr. Williams was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by a 12-member jury that included just one Black person—at a time when St. Louis County was 20% Black.

Over two decades later, the sitting St. Louis County prosecutor joined efforts to stop Mr. Williams’s execution and admitted that trial prosecutors used racial bias when selecting the jury. Nevertheless, reviewing courts and other authorities declined to intervene. Marcellus Williams, 55, died by lethal injection on September 24, 2024.

Just one day before the execution, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson defended his choice to do nothing. “The facts are, Mr. Williams has been found guilty, not by the governor’s office, but by a jury of his peers, and upheld by the courts.”

Joseph Amrine speaks at a rally to protest the execution of Marcellus Williams in 2024. Mr. Amrine was exonerated in 2003 after spending 17 years on Missouri’s death row for a crime he did not commit. (Associated Press)

Like the governor’s statement—which said nothing about the racial makeup of Mr. Williams’s jury or the prosecution’s admission of bias—modern defenses of criminal law, mass incarceration, and the death penalty regularly reference jury decision-making as inherently sound, dignified, and sacred. The citizen jury has long been a bedrock of America’s constitutional system, lauded by founding fathers and Supreme Court justices alike.

Of course, “representative” and “jury of one’s peers” have curious meanings when, for much of this nation’s history, the methods used to select juries have been strict, narrow, sexist, and racist.

Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th centuries, as the “Black criminal” stereotype grew common and widespread, jury trials were among the primary tools used to enforce criminal law, and a “good jury” was invariably male and white. In 1986, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Batson v. Kentucky established a procedure for courts to intervene when racial bias infects jury selection. But jury discrimination remains widespread today. Though modern research endorses the value of diverse juries, they remain rare and elusive, even in death penalty cases where the consequences of error are greatest.

At a time when executive orders have denounced “D.E.I” as “illegal,” “immoral” and “shameful,” some may find it tempting to dismiss jury discrimination concerns, too. Guilt is guilt and innocence is innocence, regardless of who weighs the evidence—right? In fact, growing research indicates that diverse juries deliberate better and more deeply, reaching more accurate and less biased verdicts.

Bedrock of Democracy

“Other than voting,” the U.S. Supreme Court explained in 2019, “serving on a jury is the most substantial opportunity that most citizens have to participate in the democratic process.”

Jury service is a right of citizenship—and like voting and holding elected office, Americans’ ability to exercise that right has historically been shaped by discrimination.

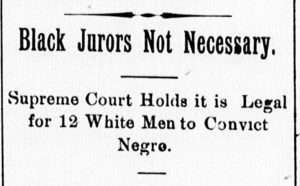

A headline in the March 14, 1903, issue of South Carolina’s Lancaster Ledger newspaper reported the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brownfield v. South Carolina, 189 U.S. 426 (1903). The Court upheld a Black man’s conviction by an all-white jury, in a county where 80% of registered voters were Black. (Library of Congress)

From the end of the Civil War through the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, proponents of white supremacy used poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and violent intimidation to suppress Black voting rights—particularly in the South, where most Black Americans lived. Jury summonses were regularly compiled using voter registration lists, and reflected the same racial exclusion seen in the voting booth. Black communities came to expect little justice from courts where the promise of trial by [white] jury only served to reinforce the racism and subjugation of life under Jim Crow.

“Negro Justice, an unwritten, de facto, separate legal system, served as the foundation for jurisprudence between Blacks and whites,” the FBI concluded in a 2006 report summarizing its re-investigation of the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. “A system where the gravity of the crime was determined in large part by its impact on whites. The Black community had almost no recourse when … crimes [were] committed against Blacks by whites.”

This all-white, all-male Mississippi jury acquitted Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, two white men, in the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. Both men later confessed in a magazine interview. (Bettmann, Getty Images)

The Civil Rights era brought many high-profile legal victories. One lesser-known win, the Supreme Court’s 1986 decision in Batson v. Kentucky, created a formal process to enable trial courts to protect against racial discrimination during jury selection.

Before Batson, trial lawyers could generally use a limited number of “peremptory strikes” to remove potential jurors from the jury pool for any reason and without explanation. After Batson, if the opposing lawyer alleged that peremptory strikes had been used to exclude jurors based on race, and if the judge found enough evidence to support that suspicion, the challenged lawyer would have to explain the reasons behind those strikes. Then the judge would have to decide whether those reasons were based in racial discrimination; if so, the judge could restore the struck jurors to the jury pool.

Justice Thurgood Marshall voted with the Batson majority but, in a concurring opinion, warned the decision would not be enough to end jury discrimination. As the Court’s first Black justice and the only one with experience defending Black defendants in the deep South, Justice Marshall predicted that prosecutors would simply learn to hide their race-motivated strikes behind race-neutral explanations. EJI’s 2021 report, Race and the Jury, explains that post-Batson developments have largely met those expectations. As recently as last November, The New Yorker reported on racial discrimination uncovered in the selection of death penalty juries in Alameda County, California.

The nine justices of the United States Supreme Court in 1986.

“In every study that I know of that has been done across the country, looking both in state courts and in federal courts, there has been a universal finding,” attorney Elisabeth Semel told The Washington Post in 2021. “The exercise of racially discriminatory peremptory strikes remains an ever-present feature of the jury selection system. So, you can pick California, you can pick North Carolina, you can pick Connecticut, you can pick the state of Washington, Oregon, on and on. And the results are unremarkably the same.”

Despite decades of limited progress, the struggle to eliminate jury discrimination continues. “The right to a fair trial before an impartial jury of one’s peers is one of the criminal legal system’s most basic principles,” law professor and longtime defense lawyer Stephen Bright wrote in 2024. Advocates have long argued that the appearance of discrimination tarnishes the system’s legitimacy and violates the rights of excluded jurors. Modern research also indicates that jury discrimination skews verdicts.

A 2012 review of a sample of Florida felony trials found that all-white juries convicted Black defendants at a significantly higher rate than white defendants—but adding Black people to the jury pool largely eliminated that racial conviction gap. Similarly, a 2001 study of 340 capital trials found that a greater proportion of white jurors to Black jurors on a trial jury corresponded to a greater likelihood that a Black defendant would be sentenced to death; this was particularly true in cases with white victims. In contrast, studies indicate that racially diverse juries probe evidence more deeply and decide cases more fairly.1 See Dennis J. Devine et al., “Evidentiary, Extraevidentiary, and Deliberation Process Predictors of Real Jury Verdicts,” Law & Human Behavior 40, no. 6 (2016): 670-82; Samuel R. Sommers, “On Racial Diversity and Group Decision-Making: Identifying Multiple Effects of Racial Composition on Jury Deliberations,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (2006): 597-612.

“Although equal access and the attempt to remedy historical injustices are important, and many would say noble considerations,” wrote Dr. Samuel Sommers, a Tufts University professor who has authored several seminal studies exploring racial diversity’s effect on jury decision-making, “the present findings provide evidence for another, often overlooked justification for promoting diversity: In many circumstances, racially diverse groups may be more thorough and competent than homogeneous ones.”

This is precisely the type of decision-making required in matters of life and death.

Getty Images

Exonerated

Since 1973, at least 200 Americans under sentence of death have been exonerated, meaning they have been declared legally innocent and released from death row. “For every nine people who have been executed, we’ve actually identified one innocent person who’s been exonerated and released from death row,” EJI Director Bryan Stevenson has observed. “In aviation, we would never let people fly on airplanes if, for every nine planes that took off, one would crash.” Our society does, however, willingly tolerate the risk of executing an innocent person.

A sign designating a U.S. prison’s death row unit. (Michael Brennan, Getty Images)

The vast majority of criminal convictions today result from plea bargains—agreements in which defendants plead guilty in exchange for reduced charges and/or a negotiated sentence recommendation. But jury trials remain influential because plea negotiations take place in the “shadow of the trial”: prosecutors’ decisions on whether to offer, accept, or reject pleas are shaped by the likelihood of conviction at trial. And that is, in part, dependent on what kind of jury prosecutors believe they can pick.

Compared to the average criminal case, death penalty cases are much more likely to go to jury trial. In some states, including Alabama, even when a defendant pleads guilty to a death penalty charge, a jury must hear the evidence and decide if it is enough to convict. Despite this greater reliance on juries, it is difficult to study jury discrimination and case outcomes—even in death penalty cases—because court transcripts and other case records often fail to document juror characteristics like race. Nevertheless, EJI has recorded more than a dozen cases of exoneration where Black people were underrepresented or wholly excluded from the trial jury.

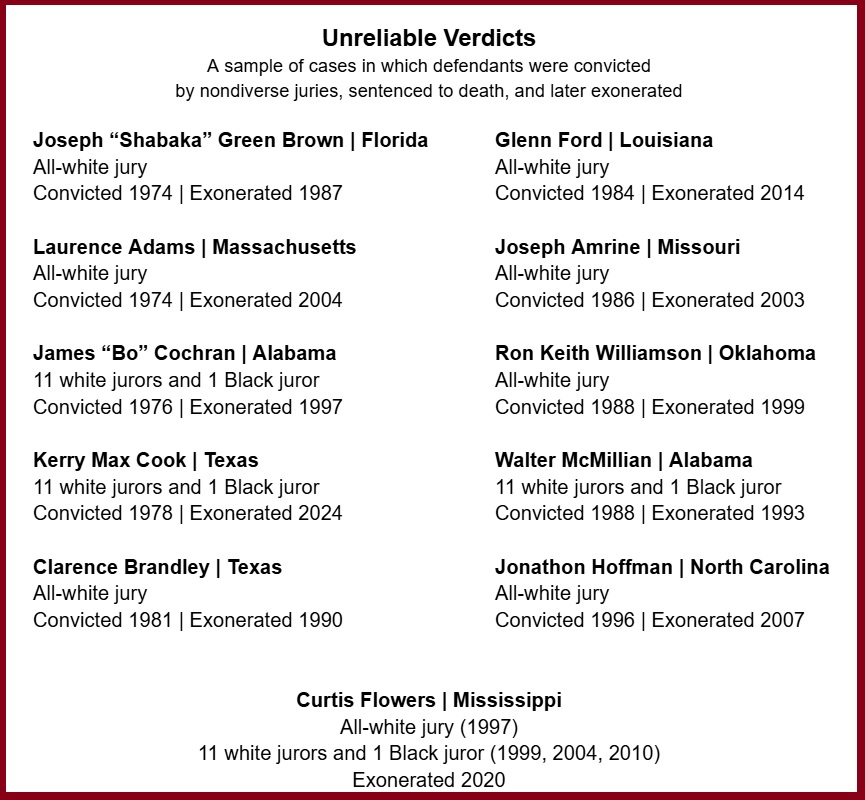

For more information about these cases, explore Unreliable Verdicts: Racial Bias and Wrongful Convictions.

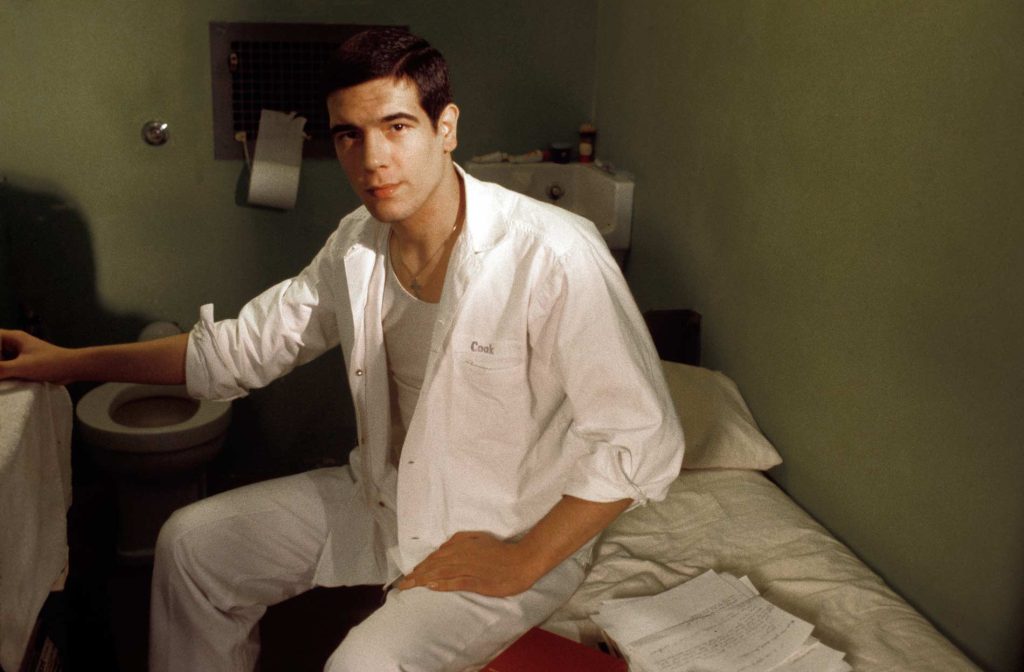

In 1978, Kerry Max Cook was convicted of killing a young white woman in Smith County, Texas. The county was then 22% Black, but Mr. Cook recalls the jury included just one Black member. “I became aware of the race and jury issue while I was on death row,” Mr. Cook told EJI in 2024. “That’s when I learned about Batson. But race plays a huge part in who gets acquitted, and who gets a fair trial. Even when you’re white, and especially when you’re poor.”

After his conviction was reversed in 1996, Mr. Cook accepted a plea deal and immediate release while still maintaining his innocence. In 1999, DNA results cleared him of the murder, and in 2024, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals declared Mr. Cook innocent.

Kerry Max Cook on death row in Texas in 1979. (Associated Press)

In Monroe County, Alabama, in 1988, Walter McMillian was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a young white woman. The trial lasted only a day and a half and, though Monroe County was nearly 40% Black, the jury included 11 white jurors and one Black juror. Mr. McMillan was convicted despite testimony from multiple Black alibi witnesses placing him at a church fish fry at the time of the crime. The State’s key witness later recanted his trial testimony, but it took several years of litigation and media coverage for the State to agree to drop all charges. Mr. McMillian was exonerated and released from death row in 1993.

Walter McMillian, with arm raised, celebrated with family, friends, and attorney Bryan Stevenson after his 1993 release from Alabama’s death row.

The case of Curtis Flowers is perhaps the closest thing to a real-life case study on race, jury selection, and wrongful conviction. From his 1996 arrest to his exoneration in 2020, Mr. Flowers stood trial six times on charges of robbing and killing four people in Winona, Mississippi. He was tried in Montgomery County, where more than 40% of residents are African American.

After an all-white jury convicted Mr. Flowers in 1997, an appellate court found a Batson violation and ordered a new trial. He was convicted by a jury of 11 white jurors and one Black juror in 1999, but that conviction was also reversed. A 2004 retrial, again heard by a jury of 11 white jurors and one Black juror, resulted in another conviction—and another reversal. The fourth and fifth trials featured juries with significantly greater Black representation: five Black jurors in 2007 and three Black jurors in 2008. These juries heard the entirely circumstantial case against Mr. Flowers and could not reach a unanimous verdict; those two trials ended as mistrials.

In the final trial in 2010, a jury of 11 white jurors and one Black juror convicted Mr. Flowers and he was again sentenced to death. On appeal in 2019, a 7-2 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the conviction based on a Batson violation. “The State’s relentless, determined effort to rid the jury of Black individuals,” the Court opined, “strongly suggests that the State wanted to try Flowers before a jury with as few Black jurors as possible, and ideally before an all-white jury.” In 2020, Mississippi officials dropped all charges and Mr. Flowers was released.

After six trials over 24 years, Curtis Flowers was exonerated and released from Mississippi’s death row in 2020. (Associated Press)

As late as July 2018, Mississippi’s Clarion Ledger newspaper observed that there was “no direct evidence against [Mr.] Flowers and no reliable evidence placing him near the scene or linking him to the murder weapon.” Yet in four of six trials—each time Mr. Flowers was tried in a proceeding with one or fewer Black jurors—the jury heard the shoddy evidence, voted to convict, and condemned him to die. In contrast, each time Mr. Flowers was tried by a jury with significant Black representation—including the one time he was tried by a jury with racial proportions nearly matching Montgomery County’s overall population—the evidence proved too weak to support a unanimous verdict. In those proceedings, the juries held the prosecution to its burden, and the resulting mistrials avoided convicting and condemning a man now widely recognized as innocent.

The review of exoneration juries is largely anecdotal because incomplete records make a national review nearly impossible. New research focused on Alabama death sentences has yielded a more comprehensive view.

Cathryn Virginia

Eye on Alabama

Last year, Alabama executed six people—the most of any of the nine states to carry out executions in 2024, including Texas and Florida. The state’s commitment to capital punishment has been largely unshaken, even though courts have reversed at least 170 Alabama death sentences since 1980, at least nine people have been exonerated and released from Alabama’s death row since 1973, and multiple executions carried out in Holman Prison’s death chamber since 2018 have been botched and torturous.

In January 2024, Alabama reached a new level of extremism when it became the first state in the country to execute a person using suffocation by nitrogen gas. As of February 2025, Alabama has used the method four times.2 Alabama used nitrogen gas to execute Kenneth Smith on January 25, 2024, Alan Eugene Miller on September 26, 2024, Carey Dale Grayson on November 21, 2024, and Demetrius Frazier on February 6, 2025. For these reasons, it is particularly critical to interrogate the way Alabama imposes death sentences and selects the juries empowered to play a central role.

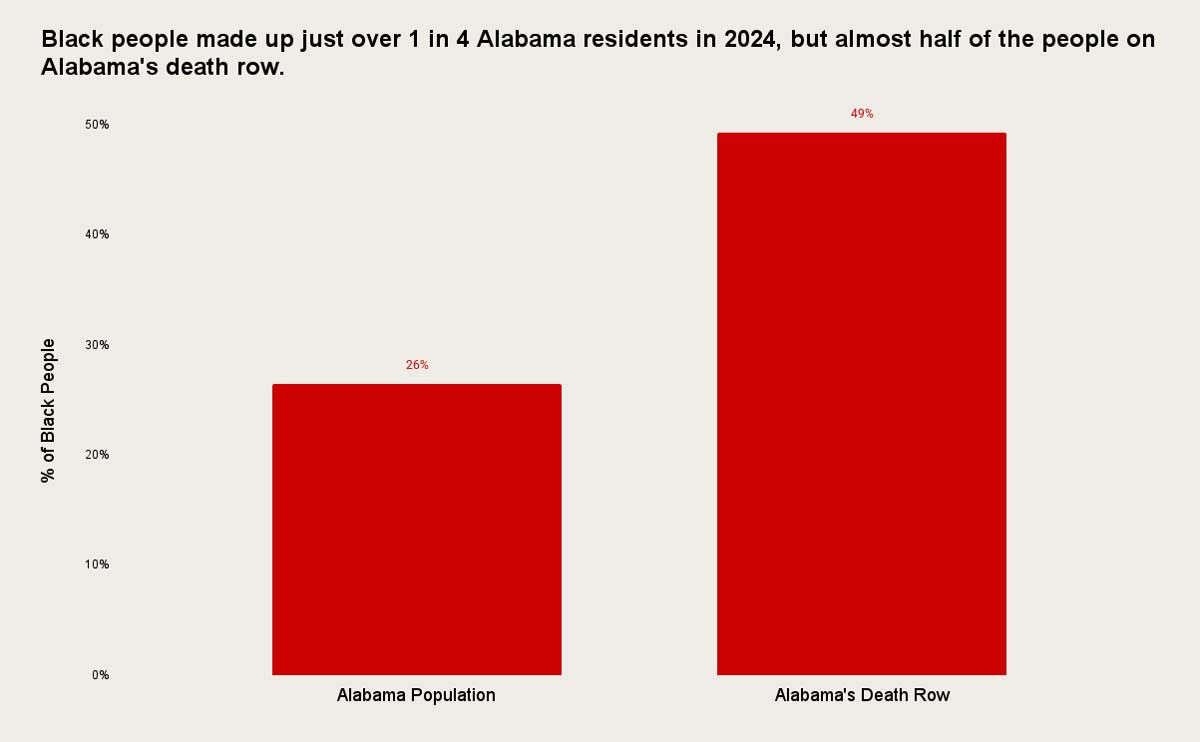

EJI is a nonprofit law office that has handled death penalty appeals in Alabama for more than 35 years. Over several years, we have compiled jury composition records for 122 of the 162 individuals on Alabama’s death row—about three in four.3 As of October 14, 2024, Alabama’s death row held 162 individuals under sentence of death. This group included five women and 157 men; 80 Black people, 80 white people, and two people whose race the State categorized as “other.” The men and women facing execution in Alabama were convicted and sentenced across a span of 40 years, from 1984 to 2024, and many are still in the midst of appealing their convictions and death sentences. The data reveals a state death penalty where Black exclusion from jury service is normal operating procedure.

As detailed in the report, Unreliable Verdicts: Racial Bias and Wrongful Convictions, more than half (64 cases, or 52.5%) of these 122 cases were decided by juries with Black underrepresentation. That means the jury included fewer Black jurors than would be proportional to the county’s Black population at the time of trial. More than a third of these 122 cases (48, or 39.3%) were decided by juries with one or fewer Black jurors: 25 cases (20.5%) had juries with one Black member and 23 cases (18.9%) were heard by all-white juries.

These and other numbers detailed in Unreliable Verdicts describe an Alabama death penalty that relies on the decision-making of juries, but regularly fails to empanel juries that accurately represent the racial makeup of the community. Under this system, the voices and influences of Black people are disproportionately excluded from the decision-making process when applying the state’s harshest penalty—while the proportion of Black people on Alabama’s death row is nearly double their representation in the state as a whole.

“If our legal system treats you better if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent,” says EJI Director Bryan Stevenson, “if we look the other way when convictions and sentences are imposed in clear violation of constitutional requirements and when we tolerate the kind of racial bigotry and exclusion that is found in Alabama’s system of jury selection, we cannot legitimately claim that we have the right to kill people to show that killing is wrong.”

In 2015, after 30 years on Alabama’s death row for two Jefferson County robbery-murders he did not commit, Anthony Ray Hinton was exonerated and released. Later reflecting on his case, Mr. Hinton recalled how the racial realities of the court system were stacked against him from the time of his 1985 arrest.

I said, “Well, you got the wrong person. I ain’t done none of that!” And [a white detective] continued to look at me and he said, “You know, I don’t care whether you did it or didn’t do it. But I’mma make sure you’ll be found guilty of it. And there’s five things that’s going to convict you. He said, “Number one, you’re Black. Number two, a white man is gonna say you shot him. Whether you shot him or not, I don’t care.” He said, “Number three, you gonna have a white prosecutor.” Number four, you gonna have a white judge. And number five, more than likely you gonna have an all-white jury.” And he continued to look at me. And he said, “You know what that spell? Conviction, conviction, conviction, conviction, conviction.”

Anthony Ray Hinton endured 30 years on death row in Alabama for crimes he did not commit. (Rob Liggins)

A New Barrier in Alabama

Since federal courts rejected EJI’s 2011 attempt to sue a district attorney’s office for repeated jury discrimination, appealing criminal convictions remains the primary way to challenge racially biased jury selection. In 2024, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals made that harder to do.

In most criminal cases, to raise an issue on appeal, the defendant must show that the issue was raised or brought up at trial, so the trial judge had a chance to consider and correct it. Alabama’s “plain error” rule has long allowed individuals appealing a death sentence to raise issues even if they were not raised at trial. Appellate courts are required to review those claims and decide if they constitute “plain error”—a big enough mistake for the court to reverse the verdict and/or sentence, to ensure that the death penalty is applied fairly and appropriately. This rule creates heightened review in capital cases and recognizes that, when imposing the state’s harshest and most permanent penalty, courts should minimize procedural barriers to achieving justice and accuracy.

However, on May 3, 2024, the criminal appeals court decided to close that path to relief for claims of racial discrimination in jury selection.

We now hold that, in an exercise of our discretion, this Court will no longer review Batson claims under our plain-error standard when those claims are raised for the first time on appeal. Instead, for a defendant to obtain appellate review of a Batson claim before this Court, even in a death-penalty case, he must raise the claim in the trial court, thereby giving that court the first opportunity to consider the claim and to issue a ruling that may be challenged as erroneous on appeal. Thus, because [the defendant in this case] did not raise a Batson claim at trial, we will not consider his Batson claim on appeal.4 Henderson v. State, No. CR-21-0044, 2024 WL 1946585, at *32 (Ala. Crim. App. May 3, 2024).

Many Batson reversals in Alabama have happened under the plain error doctrine, in cases where glaring instances of jury discrimination went completely unchallenged by trial attorneys and judges alike. The plain error rule has repeatedly served as a safety valve and a needed protection.

Ms. Edith Ferguson (pictured with her son, Charles Morton) was one of 24 Black people excluded from serving on a Dallas County, Alabama, death penalty jury. In 2009, a federal appeals court called the case’s record of jury discrimination “astonishing.”

Notably, while Alabama is increasing the barriers to litigating claims of racial discrimination in jury selection, some states have passed laws to increase courts’ ability to review convictions for racial bias. In 2009, North Carolina lawmakers enacted the Racial Justice Act, which authorized state courts to review death penalty cases, conduct hearings, and reverse death sentences where evidence established that the defendant’s race was a factor in the sentencing decision. Lawmakers repealed the law in 2013, following a political shift in the state legislature, but a 2020 court ruling allowed challenges filed before the repeal to continue. This month, the Johnston County Superior Court granted North Carolina’s fifth reversal after finding that race impacted multiple components of Hasson Bacote’s trial, including the prosecutor’s use of peremptory strikes.

California’s Racial Justice Act, passed in 2020, applies to all criminal convictions and makes it illegal for any state actor to obtain a conviction or sentence on the basis of race. In contrast, if the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals’ decision to exclude Batson claims from plain error review stands, the widespread and ongoing discrimination that leads to the selection of nondiverse juries in Alabama capital cases will be even harder to challenge, and there will be even more reason to question the reliability of death sentences in the state.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg served on the Supreme Court from 1993 to 2020. (Mark Wilson, Getty)

In 2013, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented in Shelby County v. Holder, a decision that struck down the Voting Rights Act’s requirement that counties with histories of voter discrimination be subject to heightened oversight (“preclearance”) when changing their voting rules.

“Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes [to voting laws],” Justice Ginsburg wrote, “is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Similarly, the decision to reduce Alabama appellate courts’ responsibility to review and protect against racial discrimination in jury selection—in a state where such discrimination continues to be well-documented—is hard to reconcile with the goal of a fair and just death penalty. In Alabama, and nationwide, we desperately need to maintain and strengthen our proverbial umbrellas. And perhaps most importantly of all, we must reaffirm our collective commitment to the goal of “not getting wet.”

Too Far From Perfect

Alongside the ideological, moral, historical, and legal reasons to oppose racial discrimination in jury selection, social science research has revealed another compelling reason: diverse juries are better at fulfilling the jury’s central duty to interrogate the evidence, probe the prosecution’s case, and resist bias in its decision-making. Some early arguments against jury discrimination seemed to envision a system of “balanced bias,” in which Black jurors’ alleged pro-Black bias could challenge or cancel out white jurors’ assumed pro-white bias. Research now shows that diverse juries can be a path to a greater prize: increased reliability.

By requiring jurors to engage and discuss case evidence with people who are different from them, diverse juries are less likely to presume agreement or take a shallower dive into the evidence —and that’s a benefit in all cases. While a “balanced bias” framing assumes that an all-white jury only poses a risk to a nonwhite defendant, a system that values jury diversity for its increased reliability recognizes jury discrimination as a threat to everyone.

With this information, we can hold our officials accountable for ensuring more accurate representation among the juries that decide trials in our communities. We can advocate for better recordkeeping to enable data collection and oversight to measure progress on this front. And, when able, we can encourage ourselves and our friends, relatives, and neighbors to readily fulfill the duty of jury service when called to do so.

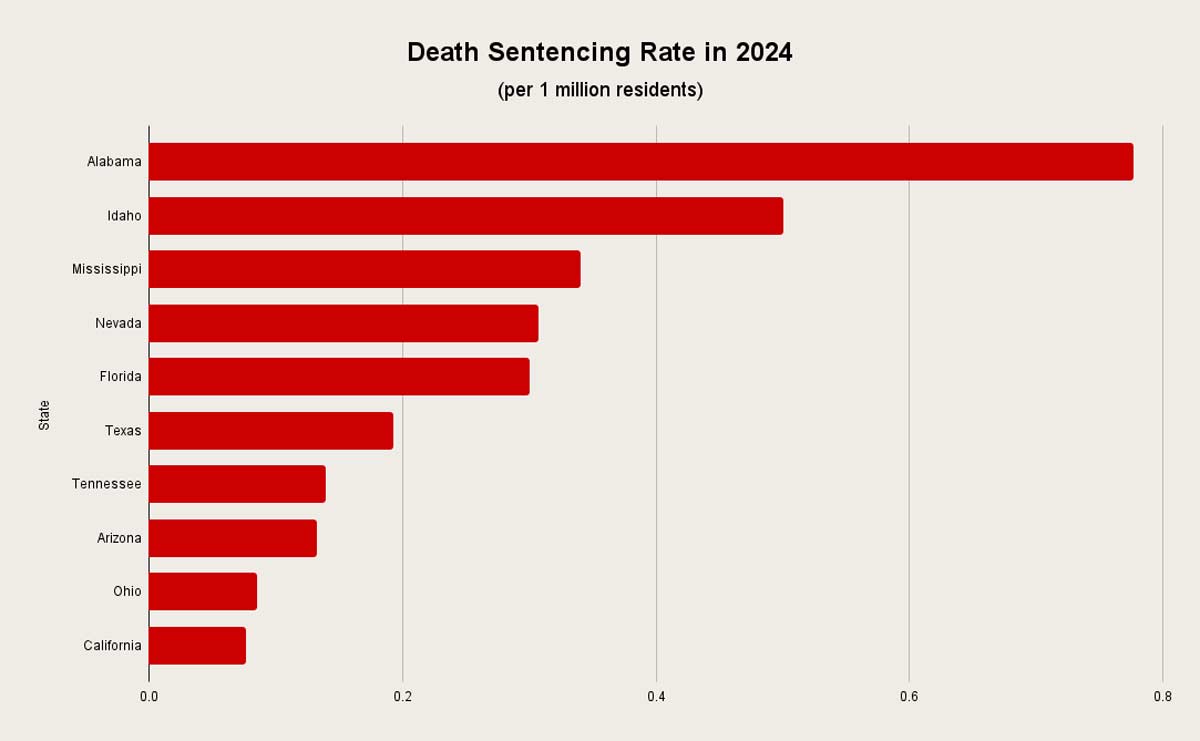

We can hope that, once achieved, these actions will yield a system of criminal law that more reliably metes out justice. Alabama’s example cautions against the consequences of doing far less. Though just 24th in the nation by population size, Alabama ranks sixth for the number of executions since 1976 (79),5 “Executions by State and Region Since 1976,” Death Penalty Information Center, accessed Feb. 7, 2025. fourth for the number of people currently on death row,6 “Death Row Overview: Prisoners on Death Row,” Death Penalty Information Center, accessed Feb. 7, 2025. third for the number of death sentences imposed in 2024 (4), and first for the rate of sentences per capita in 2024. Black people make up about one in every four Alabama residents but one of every two people on the state’s death row. And, in cases with reviewable data, more than half of those awaiting execution in the state were convicted in trials where Black people were underrepresented on the jury.

Despite these troubling figures, in 2024, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals made it more difficult to challenge jury discrimination in death cases7 Henderson v. State, No. CR-21-0044, 2024 WL 1946585, at *32 (Ala. Crim. App. May 3, 2024).—dulling a critical tool at the very time it should be sharpened.

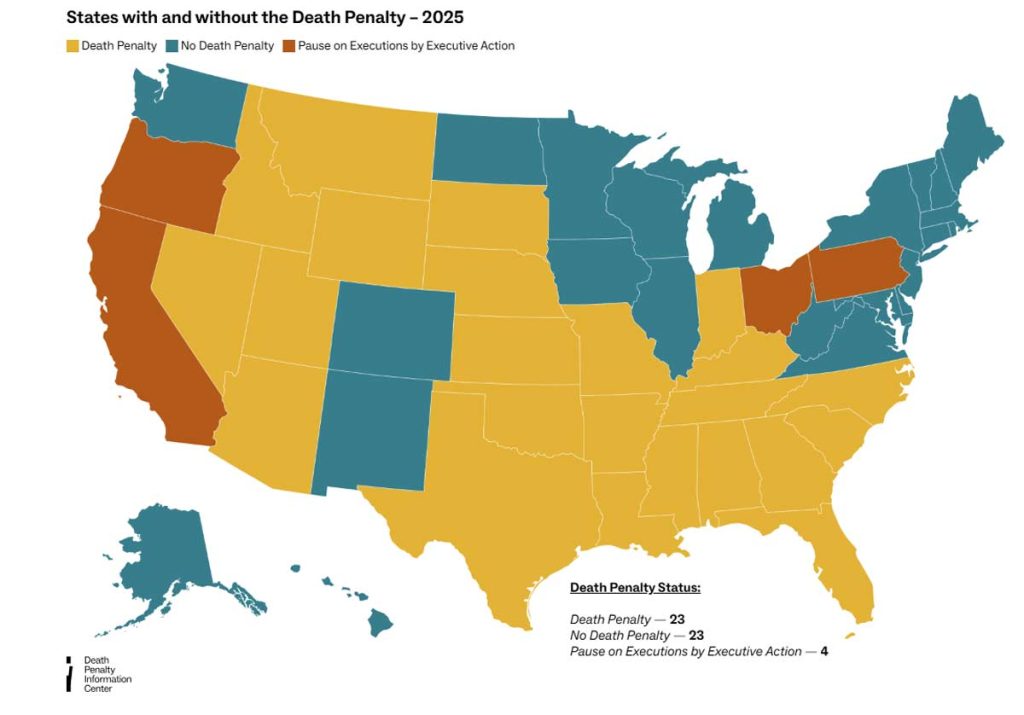

“It is better 100 guilty persons should escape,” Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1785, “than that one innocent person should suffer.” As of 2024, 23 states and the District of Columbia have embraced this call by abolishing the death penalty. In four more states, governors have imposed a hold on carrying out executions. Where the death penalty remains legal and active, increasing the diversity of juries is one tool that can increase reliability and help reduce the risk of wrongful convictions.

(Source: Death Penalty Information Center)

Research reveals that, when juries reflect the racial diversity of our nation and the communities in which they sit, jurors deliberate differently and better. Diverse juries are but one part of a fair justice system; they are not a guarantee of verdict reliability or a shield against wrongful conviction. Jury makeup is just one factor, but it’s an impactful factor, and one we have the power to shape and control. In cases that turn on determinations of credibility and require weighing circumstantial evidence, wrongful conviction is a greater risk. That risk increases with nondiverse juries that are more likely to be biased in favor of conviction and less likely to forcefully hold the State to its burden to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

A system empowered to decide life and death should strive for perfection and shudder to imagine even one inaccuracy.

A system untroubled by the possibility of error should reexamine its humanity—and reconsider its suitability to decide life and death at all.