On Friday, nearly 100 people attended an emotional unveiling ceremony outside the Douglas County Courthouse in Omaha, Nebraska, to dedicate a historical marker memorializing George Smith, who was lynched by a white mob outside the courthouse in 1891.

The new marker stands across from a second marker that acknowledges the lynching of Will Brown on the courthouse lawn in 1919 and was unveiled last year.

The placement of the two markers, which requires visitors to the courthouse to walk between them, “speaks to the importance of reconciliation,” Brenda Council, a former Omaha City Council member and Nebraska state senator, told the World-Herald at Friday’s unveiling.

“It contains a tragic but real story of the role that racial injustice played in the City of Omaha,” she said. “It’s a new day, and we need to move forward — not ignore the wounds, but acknowledge them and seek to heal from them.”

EJI worked with the Omaha Community Council for Racial Justice and Reconciliation on the markers, as well as a community soil collection at the site of the lynchings.

At Friday’s dedication ceremony, community members and state and local officials confronted their history of racial terror lynching and its legacy through song, poetry, prayer, and speakers who emphasized the healing and hope that comes from sharing the truth about our history.

/

Franklin Thomas, director of the Omaha human rights and relations department, adds soil to a jar memorializing George Smith during a ceremony on October 15, 2020.

Brendan Sullivan/Omaha World-Herald

/

Marion Burse, along with other attendees, sings “Lift Every Voice and Sing” during a marker dedication ceremony on October 7, 2022, honoring George Smith.

Eileen T. Meslar/Omaha World-Herald

/

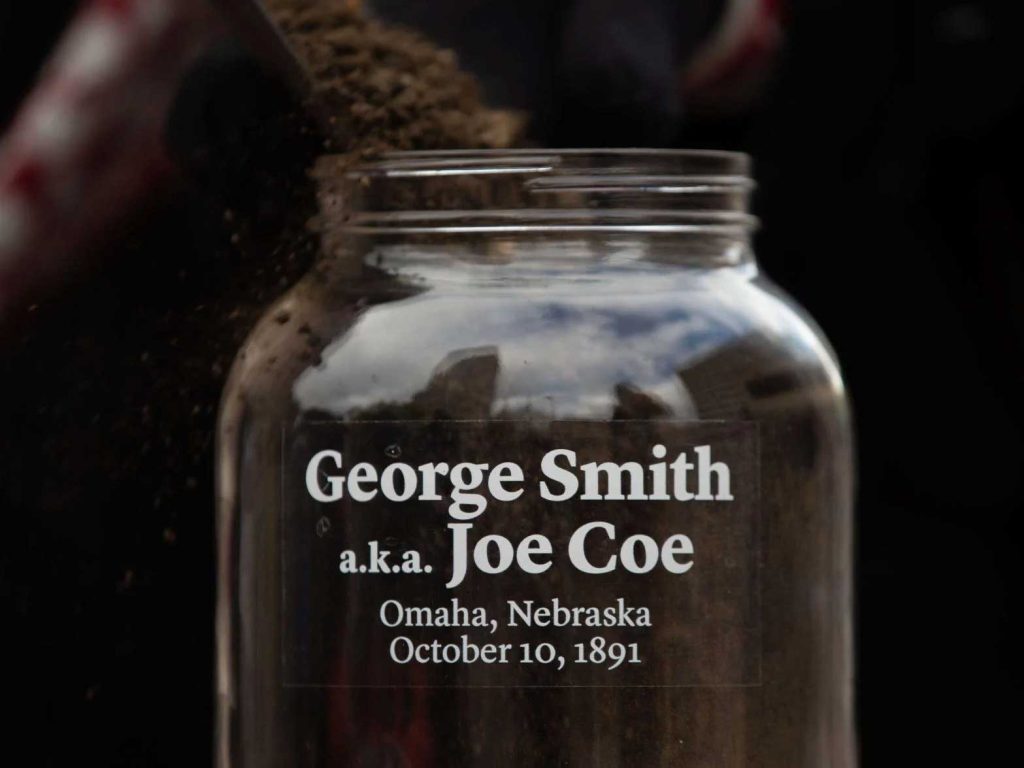

A jar of soil collected in honor of George Smith, who was lynched in 1891.

Lily Smith/Omaha World-Herald

/

The new marker honoring George Smith now sits outside the Douglas County Courthouse in Omaha, Nebraska.

Eileen T. Meslar/Omaha World-HeraldThe Lynching of George Smith

In the early hours of October 10, 1891, a mob of white people from Omaha and the surrounding counties gathered at 18th and Farnam Streets to lynch George “Joe Coe” Smith, a 20-year-old Black man.

Two days earlier, local newspapers falsely reported that a white girl died after being assaulted by a Black man. The next day, police arrested Mr. Smith—even though he had an alibi and no evidence tied him to the alleged offense.

Within hours, thousands of white men, women, and children shouting “Bring the n—-r out!” marched on the Douglas County Jail and Courthouse, calling for Mr. Smith to be hanged. White men used crowbars, sledgehammers, and chisels to break into the steel jail cell and abduct Mr. Smith.

After capturing him from armed law enforcement officers, the mob placed a rope around Mr. Smith’s neck and pushed him through the window into a crowd of over 10,000 white spectators below. They beat, kicked, and trampled Mr. Smith so severely that, by the time his body was hanged at 17th and Harney Streets, it was already lifeless. White people collected pieces of the telegraph pole used to lynch Mr. Smith as souvenirs.

Mr. Smith, a waiter at a local hotel, was survived by his wife and young daughter, who lived a block away from this site near 10th and Izard. In the end, the local coroner concluded that Mr. Smith had died of “Fright.” No one was ever held accountable for the lynching of George Smith.

Lynching in America

Between 1865 to 1950, thousands of African Americans were victims of mob violence and lynching across the U.S.

Following the Civil War, fierce resistance to equal rights for African Americans and an ideology of white supremacy led to fatal violence against Black women, men, and children. Lynching emerged as the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism, intended to intimidate Black people and reinforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Many African Americans were lynched for exercising economic freedoms, perceived violations of social customs, and accusations of crimes. Accusations against Black men by white women regularly aroused mob violence and lynching. A white person’s allegation against a Black person was rarely subject to scrutiny and often sparked violent reprisal, even when there was no evidence tying the accused to any offense.

Although many victims of racial terror lynching will never be known, more than 300 racial terror lynchings have been documented in states outside the South, including at least five in Nebraska.