Race and the Jury

Illegal Discrimination in Jury Selection

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

In too many communities, the fairness, reliability, and integrity of the legal system have been compromised by clear evidence of racial bias in the selection of juries.1 See Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection: A Continuing Legacy (June 2010). Unrepresentative juries not only exclude and marginalize communities of color, they also produce wrongful convictions and unfair sentences that disproportionately burden Black people and people of color. Our failure to remedy this longstanding problem of racial bias imperils the legitimacy of the U.S. legal system.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that an “[e]qual opportunity to participate in the fair administration of justice is fundamental to our democratic system.”2 J.E.B. v. Alabama, 511 U.S. 127, 145 (1994). The Court has insisted that eliminating racial bias in the selection of juries is necessary “to preserve the public confidence upon which our system of criminal justice depends.”3 Foster v. Chatman, 136 S. Ct. 1737, 1760 (2016) (Alito, J., concurring).

In most communities in America, Black people and people of color are significantly underrepresented in the jury pools from which jurors are selected. The law requires that the proportion of Black people in a jury pool must match Black representation in the overall population,4 See Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979); Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975). but courts routinely fail to enforce these requirements. Legal standards created by the courts make it difficult to prove discrimination and have led to a failure to address racially discriminatory practices.

When Black people and people of color do get called for jury service, they are still removed unfairly. There is widespread racial bias in the selection of key leadership roles such as the grand jury foreperson—who has significant power to shape the conduct and outcome of legal proceedings, at least in some jurisdictions.5 Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545 (1979). In criminal trials, prosecutors and judges often remove Black people after unfairly claiming they are unfit to serve on juries.

Even if people of color successfully navigate all of these barriers to jury service, they can be excluded by lawyers who have the right to use “peremptory strikes” to remove otherwise qualified jurors for virtually any reason—or no reason at all.

Courts allowed prosecutors to use peremptory strikes to prevent Black people from serving on juries throughout most of the 20th century. In a landmark case in 1986, the Supreme Court finally changed the legal requirements for proving a peremptory strike is racially biased.6 Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). But the Court’s decision in Batson v. Kentucky did not eliminate racial discrimination.

Representative juries selected without racial bias or discrimination are essential in our democracy. They are especially important because Black people are underrepresented in prosecutors’ offices and in the judiciary. More than 40% of Americans are people of color, but 95% of elected prosecutors are white.7 “QuickFacts: United States,” United States Census Bureau, accessed Nov. 18, 2020; Reflective Democracy Campaign, Tipping the Scales: Challengers Take On the Old Boys’ Club of Elected Prosecutors (Oct. 2019), 2. Similar disparities exist within the judiciary.8 See, e.g., Janna Adelstein and Alicia Bannon, State Supreme Court Diversity — April 2021 Update, Brennan Center for Justice (April 2021).

Courts, lawyers, states, and communities must make a renewed effort to address racial bias in jury selection. This problem can be solved, but it will require a more committed and determined effort than has been seen to date.

Chapter 1

A History of Discrimination in Jury Selection

The right to a jury of one’s peers is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution as a safeguard against abuses of power by state and federal governments.9 See Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 151-53, 156 (1968). Further, the right to a jury trial represents the only individual right enumerated in the 1789 Constitution, and the only right guaranteed in both the Constitution itself and in the Bill of Rights. U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 3 (“The trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury.”); U.S. Const. amend. VI (“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed…”); U.S. Const. amend. VII (establishing right to jury trial in civil cases where value at issue exceeds $20).

A jury made up of ordinary citizens acts as a “bulwark” of liberty for individuals accused of a crime by reining in overzealous or corrupt prosecutors and exposing judges who fail to protect the rights of the accused.10 Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 308 (1880) (describing the right to trial by jury as a “bulwark of [citizens’] liberties”) (quoting William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 2 (San Francisco: 1916), 2584); see also Duncan, 391 U.S. at 156-57; Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 86 (1986) (“The very idea of a jury is a body…composed of the peers or equals of the person whose rights it is selected or summoned to determine; that is, of his neighbors, fellows, associates, persons having the same legal status in society as that which he holds…. The petit jury has occupied a central position in our system of justice by safeguarding a person accused of crime against the arbitrary exercise of power by prosecutor or judge.”).

In addition to shielding individual defendants from government overreach, juries embody and sustain democracy itself by providing an “opportunity for ordinary citizens to participate in the administration of justice.”11 Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 406 (1991).

“Other than voting, serving on a jury is the most substantial opportunity that most citizens have to participate in the democratic process.”

Flowers v. Mississippi, 139 S. Ct. 2228, 2238 (2019).

Jury service empowers ordinary citizens to become “instruments of public justice” in their own communities.12 Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223, 237 (1978) (quoting Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130 (1940)); see also Albert W. Alschuler & Andrew G. Deiss, “A Brief History of the Criminal Jury in the United States,” University of Chicago Law Review 61 (1994): 876 (“Jury trial was a valued right of persons accused of crime, and it was also an allocation of political power to the citizenry.”); see also Powers, 499 U.S. at 406.

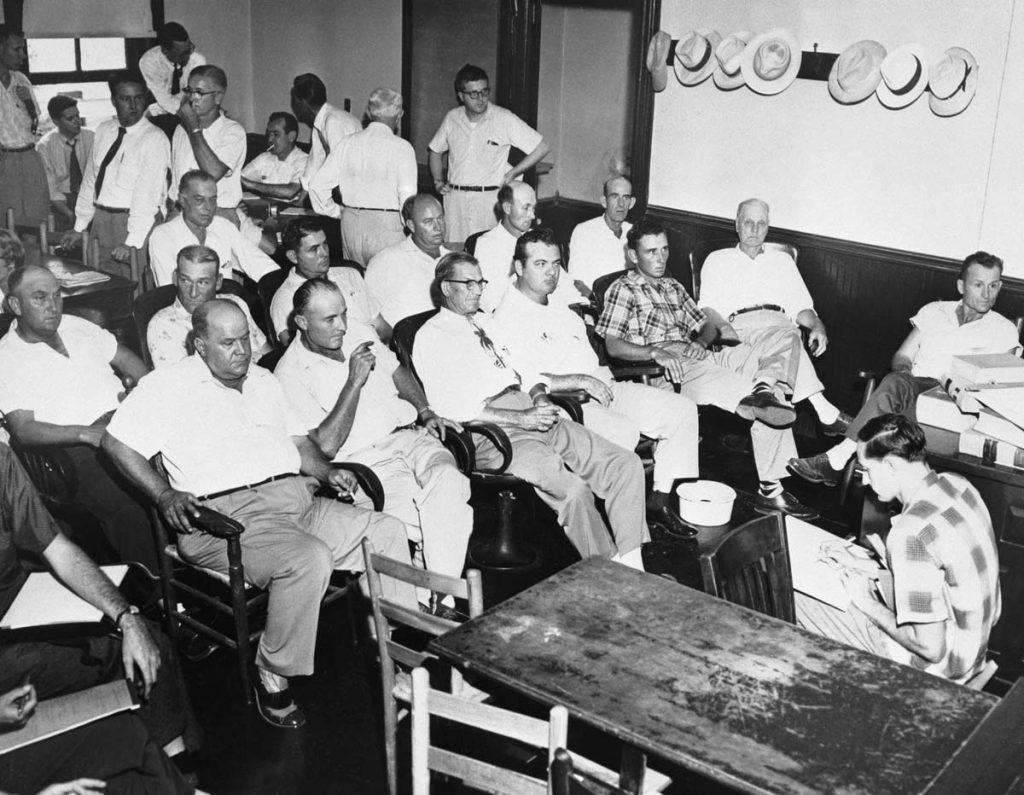

But throughout our country’s history, perpetrators of racial violence, terrorism, and exploitation of disfavored groups have escaped accountability because their criminal behavior has been ignored by all-white juries.

Black people have been excluded from jury service since America’s founding.

To justify the mass enslavement of Black people in a country that espoused freedom and liberty, an elaborate and complex mythology emerged based on the idea that Black people were not fully human and were inherently inferior to white people. This false narrative was woven into the legal system, which became a critical mechanism to enforce white supremacy.

The Constitution denied Black people the right to serve on juries13 At the time of independence, federal law granted individual states the discretion to determine juror qualifications, see Federal Judiciary Act of 1789, An Act to Establish the Judicial Courts of the United States § 29, 1 Stat. 73, 88 (1789) (“[J]urors shall have the same qualifications as are requisite for jurors by the laws of the State of which they are citizens….”) and most states linked jury eligibility to voting. See also Alschuler & Deiss, “A Brief History of the Criminal Jury,” 867, 877-79. by classifying enslaved Black people as property.14 U.S. Const. art. IV, § 2, cl. 3 (“No person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due”). Most states also excluded free Black people from jury service and denied them the right to a jury trial,15 See, e.g., An Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves (1690), reprinted in The Statutes at Large of South Carolina 7, ed. David McCord (Columbia: 1840), 343-47; An Act for the More Speedy Prosecution of Slaves Committing Capital Crimes (1692), reprinted in Statutes at Large; Being A Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 3, ed. William Henning (Richmond: 1823), 102-03; An Act for the Trial of Negroes (1700), reprinted in The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801 2, eds. James T. Mitchell and Henry Flanders (Harrisburg: 1896), 77-78 (limiting jury service to freeholders, for trials of Black people); State v. Ben, 8 N.C. 434, 435-36 (1821) (describing North Carolina’s system, which denied enslaved people the right to jury trial); An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing Negroes and Other Slaves in this Province (1755), reprinted in The Colonial Records of the State of Georgia 18, ed. Allen Candler (Atlanta: 1910), 102, 108-110 (limiting jury service in trials of free and enslaved Black people to freeholders). Other laws prohibited free and enslaved Black people from testifying in court, making exceptions only in cases involving charges against other Black people, where “other evidence proved insufficient,” or where the charges involved conspiracy to harm a white person. See, e.g., An Act For Regulating of Slaves (1702), reprinted in The Colonial Laws of New York from the Year 1664 to the Revolution 1, ed. J.B. Lyon (Albany: 1894), 519-21; An Act Relating to Servts [sic] and Slaves (1715), reprinted in Archives of Maryland, Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly of Maryland April 1715-August 1716 30, ed. William Browne (Baltimore: 1910), 283-292; Against Whom Slaves and Other Persons of Colour May Be Witnesses (1777) in An Act Concerning Slaves and Free Persons of Color, Revised Code of North Carolina No. 105 (1855). leaving African Americans unprotected from abusive prosecutions and unfair convictions and sentences. This exclusion also allowed for the murder, rape, assault, and economic exploitation of Black women and men, because all-white juries refused to hold the perpetrators accountable.

Black citizens made progress toward political equality during the 12-year period after the Civil War known as Reconstruction. Under the protection of federal troops stationed in the South to enforce the newly established rights of formerly enslaved people, many Black men voted and were elected to local, state, and federal government positions, including 16 African Americans who served in Congress.16 Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Collins, 2014), 352-55. (“Despite the overall pattern of white political control, the fact that well over 600 blacks served as legislators…represented a stunning departure in American politics.”).

Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed race-based discrimination in jury selection.17 Currently codified at 18 U.S.C. § 243 (2010) (“No citizen possessing all other qualifications which are or may be prescribed by law shall be disqualified for service as grand or petit juror in any court of the United States, or of any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”). The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, ratified in 186818 National Archives, “Documents for July 9th: 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” and 1870,19 National Archives, “Document for February 3rd: 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” respectively, guaranteed Black men the right to vote and serve on juries and provided legal protections against racial discrimination.20 While the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited the exclusion of Black men from voting, see U.S. Const. amend. XV, it left women of all races disenfranchised until the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, which established the voting rights of American women. U.S. Const. amend. XIX. In practice, the vast majority of Black men and women remained disenfranchised throughout much of the 20th century as a result of racially discriminatory state laws in the South and federal non-enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment. It was not until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that Black voting rights became a widespread reality. See Henry Louis Gates Jr., Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow (New York: Penguin Press, 2019).

Racially integrated juries in some jurisdictions enforced the rights of Black defendants and held white perpetrators of racial violence accountable for their crimes.21 See Douglas L. Colbert, “Challenging the Challenge: Thirteenth Amendment as a Prohibition Against the Racial Use of Peremptory Challenges,” Cornell Law Review 76, no. 1 (1990): 55 (noting twelvefold increase in federal prosecutions of perpetrators of racial violence between 1870 and 1872; in 1872, over 90% of those cases resulted in jury verdicts of guilt). In most of the South, however, the failure to enforce anti-discrimination laws meant that Black people continued to be denied the basic rights of citizenship, including jury service.22 See James Forman, Jr., “Juries and Race in the Nineteenth Century,” The Yale Law Journal 113, no. 4 (2004): 931 (“[A]ccording to black papers of the day, exclusion was the more common phenomenon in most counties.”).

White resistance to racial equality grew increasingly violent during this period.

From 1865 to 1876, more than 2,000 African Americans were the victims of racial terror lynchings.23 Equal Justice Initiative, Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence After the Civil War, 1865-1876 (2020), 44, 48-51. EJI documented 34 mass lynchings during the Reconstruction era. Id. at 5. Racially motivated massacres and public spectacle lynchings were widespread, with thousands of white people participating in public acts of torture.

Perpetrators of terror—who included community leaders, elected officials, and law enforcement officers—committed brutal acts of violence in broad daylight, sometimes “on the courthouse lawn,”24 Sherrilyn Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-First Century (Boston: Beacon Press, 2007). with no fear of prosecution or conviction in an all-white legal system. As a Select Committee of the Senate outlined in the Report on Alleged Outrages in the Southern States in 1871, “In nine cases out of ten the men who commit the crimes constitute or sit on the grand jury, either they themselves or their near relatives or friends, sympathizers, aiders, or abettors.”25 Report on the Alleged Outrages in the Southern States by the Select Committee of the Senate (Washington, D.C.: 1871), 179 (quoting Judge Daniel Russell of North Carolina); Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. 158 (1871) (statement of Senator Sherman quoting the report).

The same all-white juries that refused to hold white people accountable for killing Black people readily convicted Black people and imposed severe punishments for minor crimes, even in cases with little to no evidence.

As one Louisiana paper wrote toward the end of the nineteenth century, hostility to the Black citizen was such that “juries…seem to think that it is their bounden duty to render a verdict of ‘guilty as charged,’ because the accused has black skin.”26 “Prejudiced Verdicts,” Opelousas Courier, Oct. 26, 1895.

The rise of the convict leasing system in the South created an additional incentive to criminalize Black people.27 The abolition of slavery dealt a severe economic blow to Southern states whose agricultural economies relied on the labor of enslaved people. Using a loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment, Southern state legislatures created a system of convict leasing to restore the economic benefits of slavery. After enacting discriminatory “Black Codes,” which criminalized newly freed Black people as vagrants and loiterers, states passed laws authorizing prisoners to be leased to private industries. Through convict leasing, Southern states and private companies derived enormous wealth from the labor of mostly Black prisoners who earned little or no pay and faced inhumane and often deadly work conditions, generations after slavery was formally abolished. See generally “A Different Kind of Slavery,” EJI, July 25, 2018; Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2009). Of growing conviction rates among Black people during this era, abolitionist author Frank B. Sanborn wrote:

[S]o customary had it become to convict any Negro upon a mere accusation, that public opinion was loathe to allow a fair trial to black suspects, and was too often tempted to take the law into its own hands. Finally the state became a dealer in crime, profited by it so as to derive a net annual income from her prisoners…The Negroes lost faith in the integrity of courts and in the fairness of juries.28 Frank B. Sanborn, “Negro Crime” in Some Notes on Negro Crime, Particularly in Georgia, ed. W.E.B. Du Bois (Atlanta: The Atlanta University Press, 1904), 5.

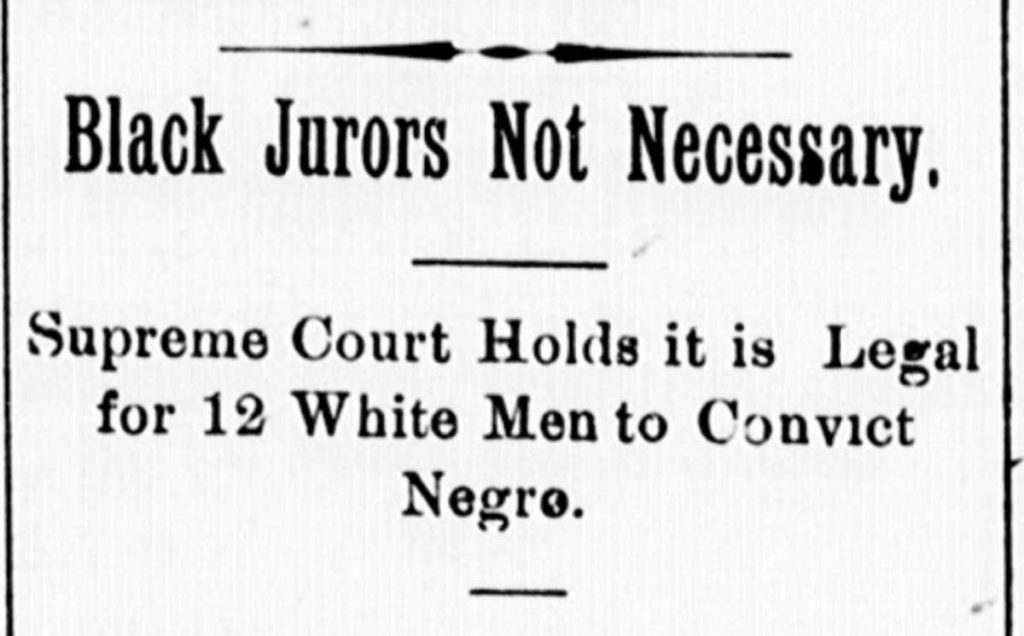

Continued white resistance to racial equality undermined the legal protections enacted by Congress during Reconstruction, while the Supreme Court largely turned a blind eye to racial violence and widespread refusal to enforce federal law.29 In Strauder v. West Virginia, the Court overturned a West Virginia state statute that explicitly restricted jury service to white citizens as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, while endorsing the use of other “qualifications” to restrict jury service. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 310 (1879) (approving laws limiting jury service to certain groups such as “to males, to freeholders, to citizens, to persons within certain ages, or to persons having educational qualifications”). Federal laws required Southern lawmakers and judges to eliminate from state statutes language that expressly excluded Black people from jury service. But they swiftly enacted new laws and practices that had the same discriminatory purpose and the same exclusionary effect.

For example, in 1898, Louisiana lawmakers amended the state constitution to “establish the supremacy of the white race.”30 See Ramos v. Louisiana, 140 S. Ct. 1390, 1394 (2020) (“Louisiana first endorsed nonunanimous verdicts for serious crimes at a constitutional convention in 1898. According to one committee chairman, the avowed purpose of that convention was to ‘establish the supremacy of the white race[.]’”). Oregon also operated under a nonunanimous jury system, see Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972), enacted in 1934 in response to anti-semitism and xenophobia. See Ramos, 140 S. Ct. at 1394 (“Adopted in the 1930s, Oregon’s rule permitting nonunanimous verdicts can be similarly traced to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and efforts to dilute ‘the influence of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities on Oregon juries.’”); see also “Modify the Jury Law,” Statesman Journal, Nov. 26, 1933 (“[T]he vast immigration into America [of people] from southern and eastern Europe…make[s] the jury of twelve increasingly unwieldy and unsatisfactory.”). The new constitution diluted the participation of Black jurors by permitting a felony conviction as long as nine out of 12 jurors voted to convict.31 Ramos, 140 S. Ct. at 1393-94 (Ramos was convicted by a nonunanimous jury with 10 jurors voting to convict him and two jurors voting to acquit). As a practical matter, this meant that if three Black jurors voted to acquit a Black defendant, the other nine white jurors’ votes were still enough to convict the defendant. The law effectively made the participation of Black people on juries meaningless. Despite its explicitly stated purpose to maintain white supremacy, this practice was not struck down by the Supreme Court until 2020.32 Louisiana voters approved an amendment to the Louisiana Constitution that required unanimous jury verdicts in 2018. La. Const. art. 1, § 17, amended by 2018 La. Acts 722. In 2020, the Supreme Court determined that the statute permitting nonunanimous felony convictions violated the Sixth Amendment. Ramos, 140 S. Ct. at 1408.

Throughout the early 20th century, state and local officials continued to use discriminatory tactics to keep Black people out of the jury box. Such tactics were often obvious—many local officials simply removed the names of Black people from jury rolls.33 Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 41-42, 55; Neil Vidmar and Valerie P. Hans, American Juries: The Verdict (Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2007), 71-72. Others were less blatant but no less exclusionary. The “key-man” system, for example, called for prominent white citizens to submit lists of suitable jurors to jury commissioners.34 Randall Kennedy, Race, Crime, and the Law (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), 182-84.

From the end of Reconstruction through the early 1930s, “the systematic exclusion of black men from Southern juries was about as plain as any legal discrimination could be short of proclamation in state statutes or confession by state officials.”35 Benno C. Schmidt, Jr., “Juries, Jurisdiction, and Race Discrimination: The Lost Promise of Strauder v. West Virginia,” Texas Law Review 61, no. 8 (May 1983): 1406.

The Supreme Court was indifferent to this rampant and illegal exclusion of Black people from juries. The Court repeatedly deferred to state court decisions finding no discrimination and rejected complaints about racially biased jury selection, even in cases involving the death penalty.36 See Franklin v. South Carolina, 218 U.S. 161, 168, 172 (1910) (denying relief to Black defendant sentenced to death where Court found no proof that grand jurors were excluded on basis of race: “Under this statute the Supreme Court of South Carolina held that the jury commissioners were only required to select men of good moral character, and that competent colored men were equally eligible with others for such service. We find no denial of Federal rights in this provision of the statute.”); see also Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 565 (1896); Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 592 (1896); Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U.S. 101 (1896); Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213 (1898); Tarrance v. Florida, 188 U.S. 519 (1903); Brownfield v. South Carolina, 189 U.S. 426 (1903); but see Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442 (1900) (reversing where defendant not provided opportunity to prove claim of racially discriminatory jury exclusion); Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U.S. 226 (1904) (same).

In the early 1900s, the Court addressed the total exclusion of African Americans from jury service in multiple cases where an all-white jury sentenced a Black man to death in a Texas county where African Americans comprised 25% of the population.37 Martin v. Texas, 200 U.S. 316, 318, 320-21 (1906) (denying relief to Black defendant sentenced to death for murder where, despite fact that African American population of Tarrant County was 25%, no African American jurors had ever been seated on grand or petit juries); Thomas v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278, 280-81 (1909) (regarding Harris County). Even though not one Black person appeared on a jury in any of these capital cases, the Supreme Court found that no illegal racial discrimination had occurred.38 Martin, 200 U.S. at 320-21; Thomas, 212 U.S. at 281-83.

Not until 1935, in Norris v. Alabama, did the Supreme Court call out local and state officials for illegally excluding Black people from juries because of their race. Norris involved the wrongful convictions and death sentences of nine Black teenagers charged with raping two white women in Scottsboro, Alabama, despite overwhelming evidence of their innocence.39 Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969); “Calls for Defense of Scottsboro Boys,” The Press-Forum Weekly, March 5, 1932; “Release of Negroes Demanded by Group,” The Anniston Star, July 28, 1931. The teens were tried and convicted by an all-white jury; no African American had served on a jury in Scottsboro in living memory.40 Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 596 (1935).

After advocacy organizations including the NAACP launched a campaign on behalf of the nine teenagers that garnered national attention for months, the Supreme Court reversed the convictions and admonished the jury commissioner for excluding all African Americans from the jury pool.41 Norris, 294 U.S. at 598-99. The Court reversed six other convictions on similar grounds over the next 12 years.42 Norris, 294 U.S. at 599; see also Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947); Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942); Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940); Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939); Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U.S. 613 (1938); Hollins v. Oklahoma, 295 U.S. 394 (1935).

But racially discriminatory practices remained widespread even after Norris as state officials used “more covert and less overt” methods of exclusion.43 Flowers v. Mississippi, 139 S. Ct. 2228, 2240 (2019).

Many jurisdictions continued to exclude Black potential jurors by saying that they lacked the requisite “intelligence, experience, or moral integrity”44 Hill, 316 U.S. at 401, 405 (local jury commissioners used purportedly race-neutral requirement that a grand juror must be “a householder” of “sound mind and good moral character” to exclude Black prospective jurors); see also Pierre, 306 U.S. at 359-61 (although half of parish was Black, jury venire did not include a single Black citizen where local officials used statutory qualifications like ability to read and write and “good character” to exclude Black prospective jurors). to serve, and lawyers continued to remove Black jurors using peremptory strikes.45 See, e.g., Thomas W. Frampton, “The Jim Crow Jury,” Vanderbilt Law Review 71, no. 5 (2018): 1620; Vivien Toomey Montz and Craig Lee Montz, “The Peremptory Challenge: Should It Still Exist? An Examination of Federal and Florida Law,” University of Miami Law Review 54, no. 3 (2000): 456 (“Restrictive laws on voting rights and, therefore, juror qualifications were implemented in many states, resulting in the discriminatory use of the peremptory to prevent African-Americans from serving on the petit jury when selective qualification requirements failed to eliminate them from the venire.”); see also April J. Anderson, “Peremptory Challenges at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century: Development of Modern Jury Selection Strategies as Seen in Practitioners’ Trial Manuals,” Stanford Journal of Civil Rights & Civil Liberties 16, no. 1 (2020): 19, 43-45.

Local officials in Georgia printed the names of Black residents on colored paper so they could avoid picking a Black person during the “random” drawing of names for the jury pool. Other officials kept Black people out of jury pools by relying on tax returns that were segregated by race.46 Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, 560-61 (1953) (not a single Black person selected from a jury panel of approximately 60 names drawn from a box containing names of prospective white jurors, printed on white tickets, and names of prospective Black jurors, printed on yellow tickets); Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 548-49 (1967) (noting that prior to 1965, Georgia state tax returns were “white for white taxpayers and yellow for Negro taxpayers,” that the “1964 tax digest, and all digests prior to 1964, were made up from these segregated tax returns,” that the “Negroes whose names were included in the tax digest were designated by a ‘(c)’,” and that the “jury lists for each county are required by law to be made up from the tax digest”).

In 1945, a decade after Norris, the Supreme Court upheld a Texas county’s policy of allowing exactly one African American to serve on each grand jury, even after jury commissioners testified that they had “no intention of placing more than one negro on the panel.”47 Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398, 406-07 (1945).

The Supreme Court addressed racially discriminatory peremptory strikes in Swain v. Alabama in 1965,48 Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965). but its decision made it impossible to prove intentional discrimination even when prosecutors excluded every single African American from the jury.49 Flowers, 139 S. Ct. at 2240 (“But Swain’s high bar for establishing a constitutional violation was almost impossible for any defendant to surmount, as the aftermath of Swain amply demonstrated.”).

Growing criticism finally forced the Court to adjust the legal standard for proving racial bias in jury selection. In 1986, the Court overruled Swain and held in Batson v. Kentucky that a defendant can prove racial discrimination in jury selection based on an assessment of the prosecutor’s strikes at the defendant’s trial.50 Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). But prosecutors soon found ways to avoid Batson’s new standard.