Related Work

Community Remembrance Project

EJI works with communities to confront their histories by collecting soil from lynching sites and installing historical markers.

124 results for "Prison"

EJI has been challenging racial injustice in criminal and civil cases for over 30 years.

EJI believes we need a new era of truth and justice that starts with confronting our history of racial injustice.

American history begins with the creation of a myth to absolve white settlers of the genocide of Native Americans: the false belief that nonwhite people are less human than white people. This belief in racial hierarchy survived slavery’s abolition, fueled racial terror lynchings, demanded legally codified segregation, and spawned our mass incarceration crisis.

The dehumanizing myth of racial difference endures today because we don’t talk about it.

EJI is working to change that. We’re exposing the myth and its toxic legacy in our reports and videos—and on this page. Our Community Remembrance Project is empowering communities to change the physical landscape to honestly reflect our history. And we’re using the power of place to inspire people to visit Montgomery, Alabama, to learn and reflect in our Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

American port cities from New England to New Orleans were shaped by the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Between 1501 and 1867, nearly 13 million African people were kidnapped, forced onto European and American ships, and trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas, including the British, French, and Spanish colonies that would later comprise the United States.

Two million people died during the barbaric Middle Passage.

The global trafficking that separated millions of women, men, and children from their homes, families, and cultures destabilized African countries and left them vulnerable to conquest, colonization, and violence for centuries.

And in the Americas, a caste system based on race and color emerged in tandem with legal and political systems to codify white supremacy and enshrine enslavement as a permanent and hereditary status. That racial hierarchy continues to haunt our nation today.

Coastal communities across the U.S. were permanently shaped by the trafficking of African people. Local economies in New England, Boston, New York City, the Mid-Atlantic, Virginia, Richmond, the Carolinas, Charleston, Savannah, the Deep South, and New Orleans were built around the enslavement of Black people.

Kidnapping, trafficking, abusing, and dehumanizing African people and their descendants created generational wealth for Europeans and white Americans across occupations and industries, from early European colonists to priests and popes, shipbuilders to rum and textile producers, bankers to insurers.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade generated the capital that was used to build some of America’s greatest cities and most successful companies. Many families, businesses, and institutions continue to benefit today from the enormous wealth produced by enslavement, but few have acknowledged or honestly confronted this history.

Slavery in America did not end. It evolved.

Beginning in the 17th century, millions of African people were kidnapped, enslaved, and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas under horrific conditions. Nearly two million people died at sea during the agonizing journey.

For the next two centuries, the enslavement of Black people in the United States created wealth, opportunity, and prosperity for millions of Americans. As American slavery evolved, an elaborate and enduring mythology about the inferiority of Black people was created to legitimate, perpetuate, and defend slavery. This mythology survived slavery’s formal abolition following the Civil War.

In the South, where the enslavement of Black people was widely embraced, resistance to ending slavery persisted for another century after the 13th Amendment passed in 1865. Today, 150 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, very little has been done to address the legacy of slavery and its meaning in contemporary life.

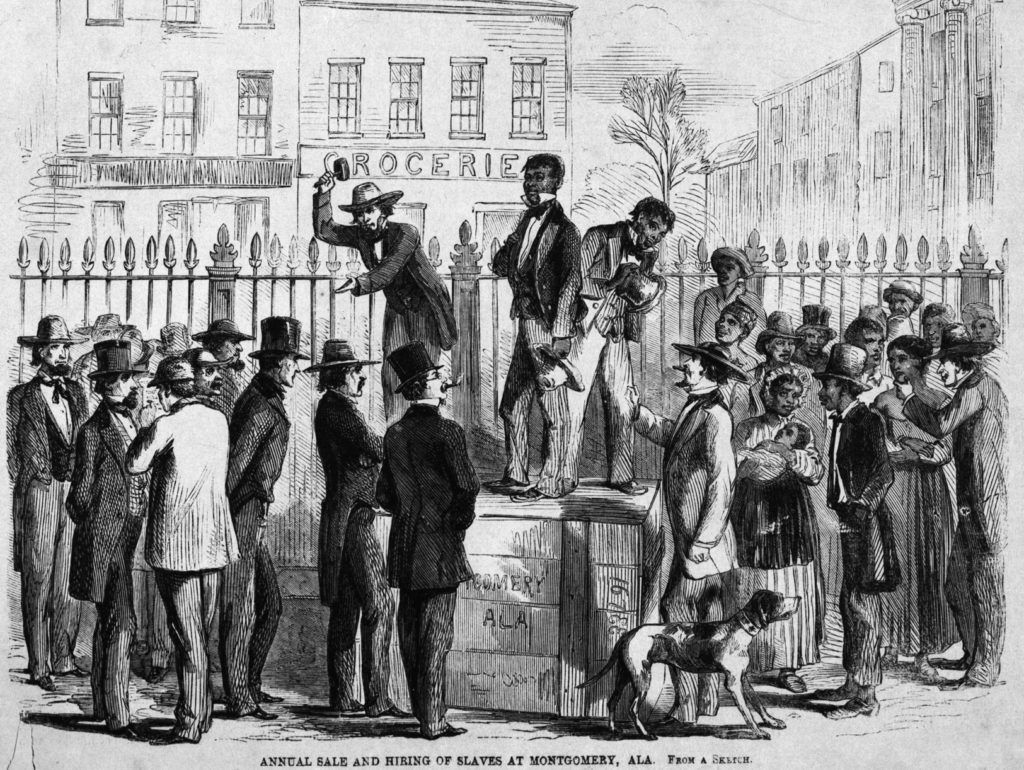

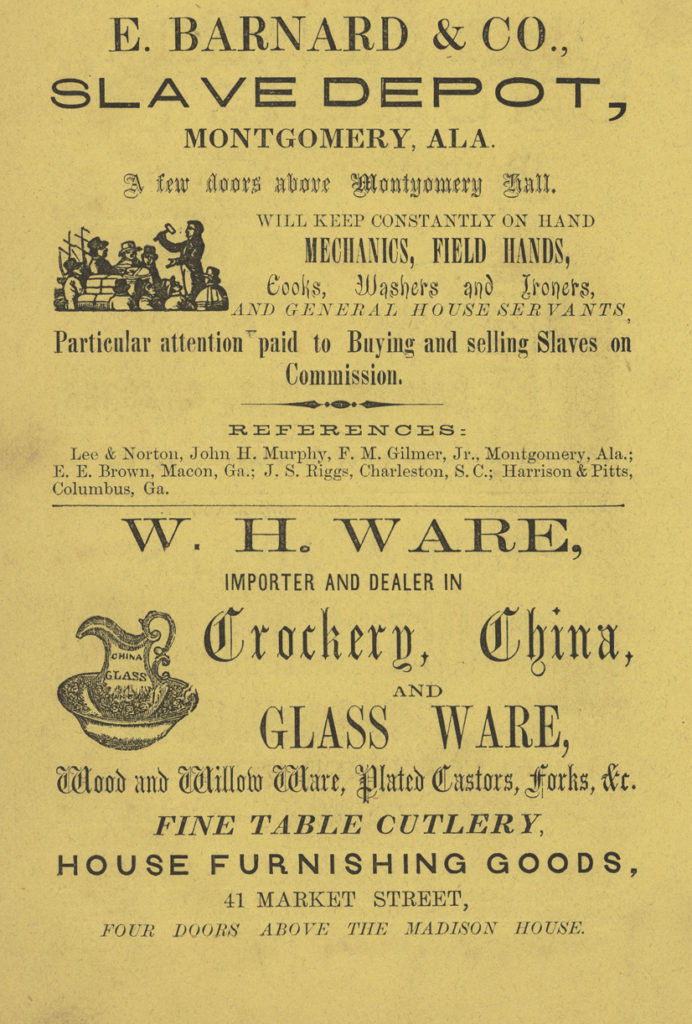

In many communities like Montgomery, Alabama—which by 1860 was the capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama—there is little understanding of the slave trade, slavery, or the longstanding effort to sustain the racial hierarchy that slavery created. In fact, an alternative narrative has emerged in many Southern communities that celebrates the slavery era, honors slavery’s principal proponents and defenders, and refuses to acknowledge or address the problems created by the legacy of slavery.

/

Imprisoned men at Maula Prison in Malawi are forced to sleep “like the enslaved on a slave ship.”

Joao Silva/The New York Times/Redux

/

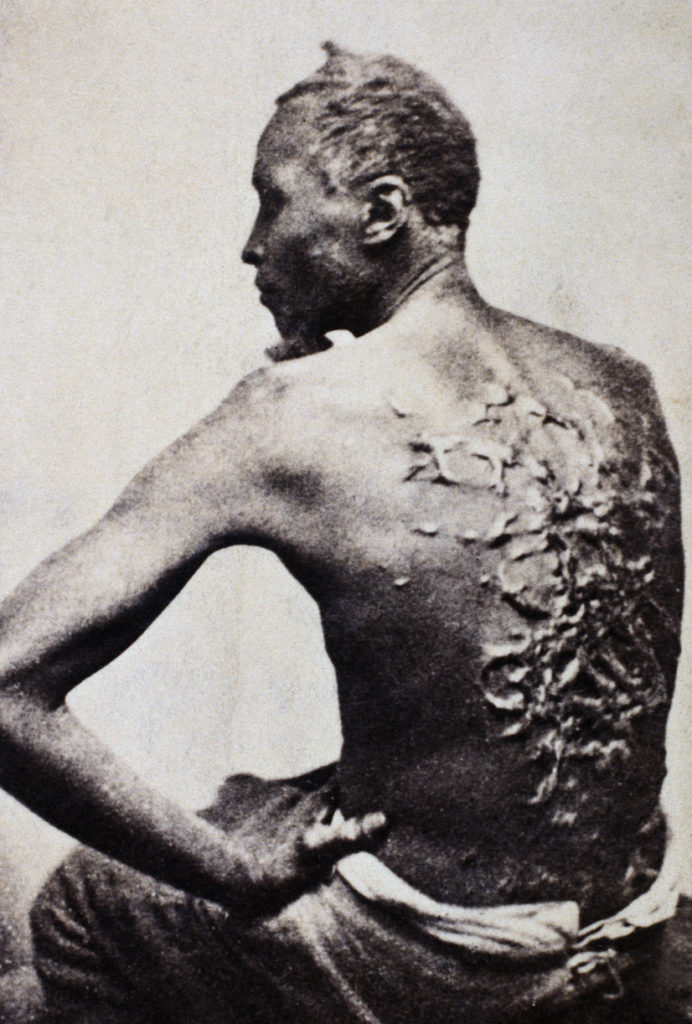

An enslaved man, Private Gordon, was beaten so frequently that the multiple whippings left graphic scars depicted in this 1863 photograph.

Donated by Corbis

/

By 1860, Montgomery was the capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama, one of the two largest slave-owning states in America.

/

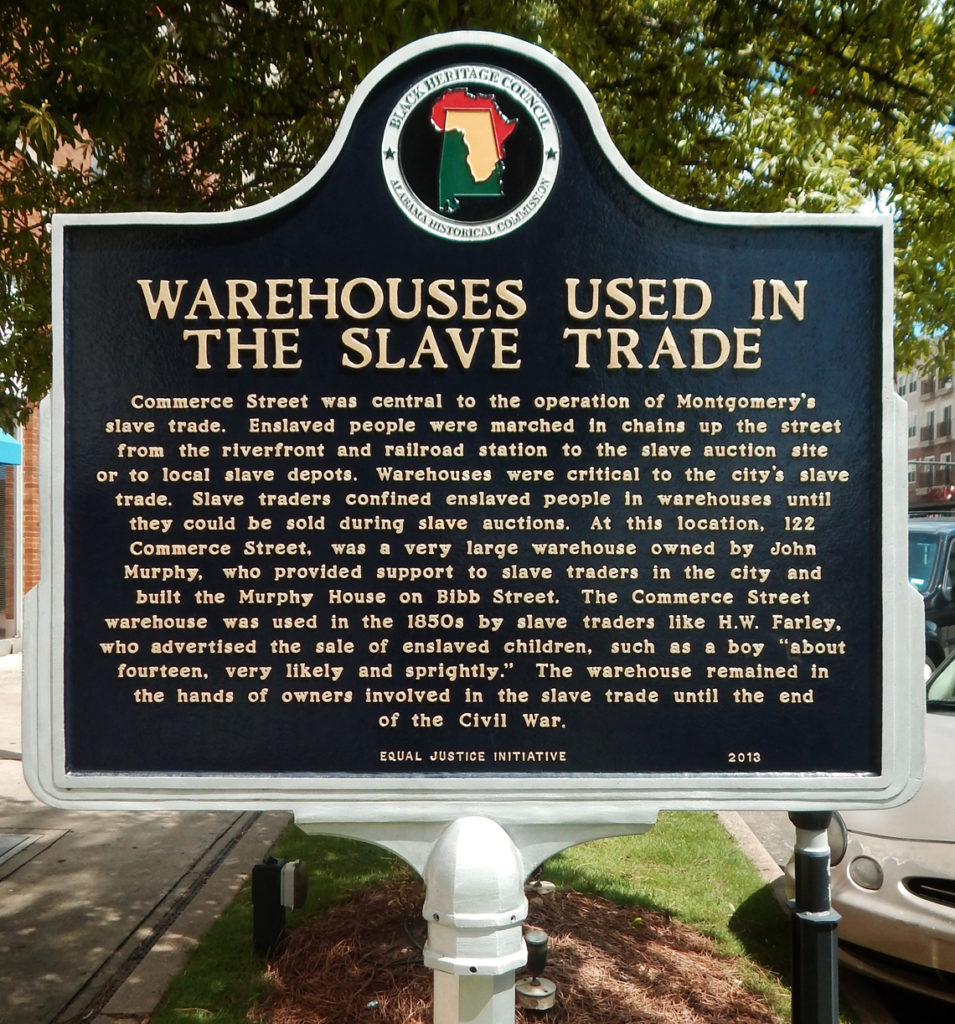

From 1848 to 1860, the probate office granted licenses to 164 slave traders in Montgomery. EJI’s Legacy Museum was built on a site where enslaved people were warehoused.

/

In 2013, with support from the Black Heritage Council, EJI erected three markers in downtown Montgomery documenting the city’s prominent role in the 19th century Domestic Slave Trade.

/

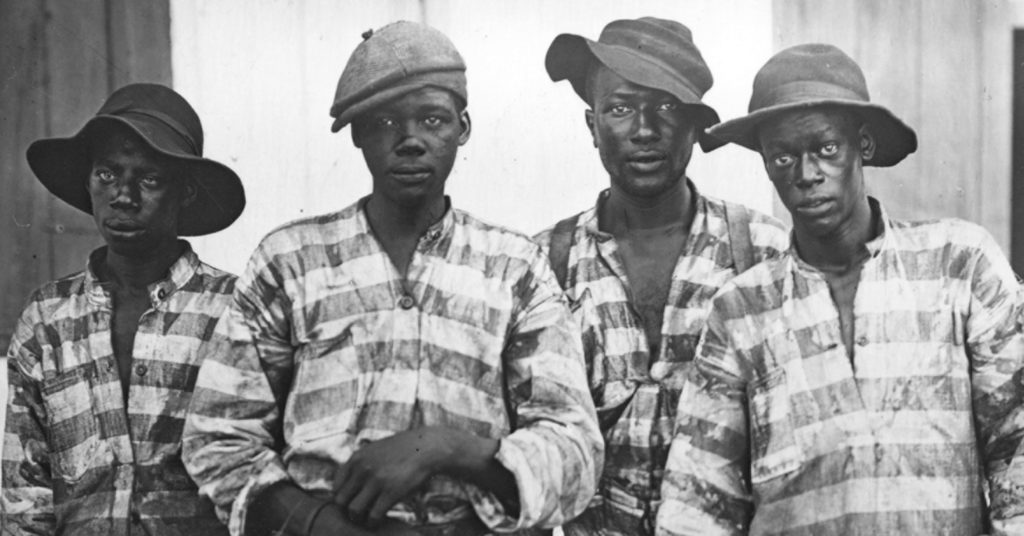

Convict leasing re-enslaved thousands of African Americans by using selectively enforced criminal codes to convict and then lease Black people to planters, mines, and other businesses.

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

/

Invocation of Confederate pride and identity accompanied white resistance to civil rights and racial equality during and following Reconstruction, at the height of the civil rights movement, and into the 21st century.

After the Civil War, Confederate veterans, former enslavers, and other white leaders organized a reign of terror to enshrine white supremacy, nullify Black voting rights, and exploit Black labor.

During Reconstruction, the 12-year period following the Civil War, lawlessness and violence perpetrated by white leaders created an American future of racial hierarchy, white supremacy, and Jim Crow laws—an era from which our nation has yet to recover.

EJI has documented nearly 2,000 more confirmed racial terror lynchings of Black people by white mobs between 1865 and 1876. Thousands more were attacked, sexually assaulted, and terrorized by white mobs and individuals who were shielded from arrest and prosecution.

White perpetrators of lawless violence against formerly enslaved people were almost never held accountable—instead, they were often celebrated. Emboldened Confederate veterans and former enslavers organized a reign of terror that effectively nullified constitutional amendments designed to provide Black people with equal protection and the right to vote.

In a series of devastating opinions, the Supreme Court blocked Congressional efforts to protect formerly enslaved people. The Court ceded control to the same white Southerners who used terror and violence to stop Black political participation, upholding laws and practices that codified racial hierarchy and embracing a new constitutional order defined by “states’ rights.”

Within a decade after the Civil War, Congress began to abandon the promise of assistance to millions of formerly enslaved Black people. Violence, mass lynchings, and lawlessness enabled white Southerners to create a regime of white supremacy and Black disenfranchisement alongside a new economic order that continued to exploit Black labor.

White officials in the North and West similarly rejected racial equality, codified racial discrimination, and occasionally embraced the same tactics of violent control seen in the South.

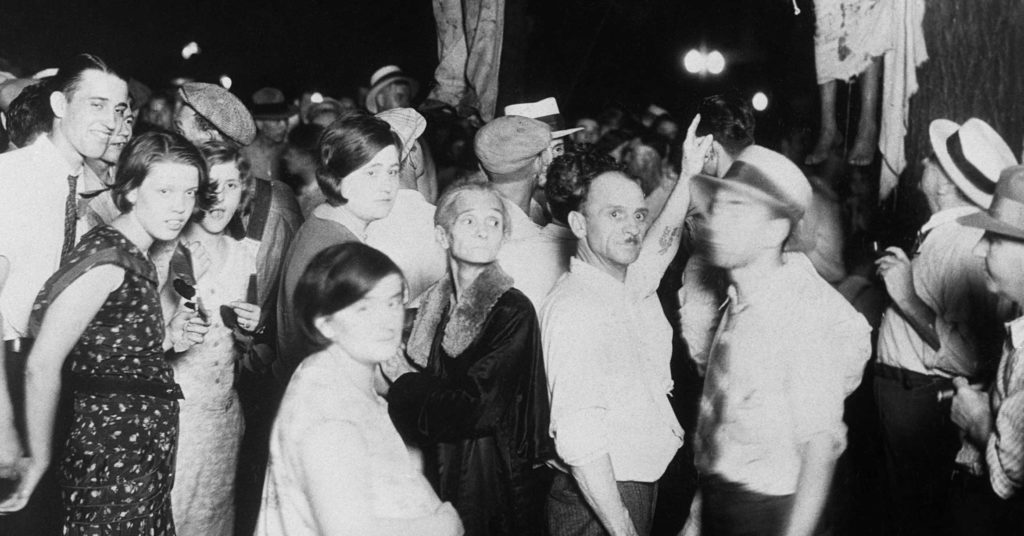

Lynching of African Americans was terrorism, a widely supported phenomenon used to enforce racial subordination and segregation.

Lynching emerged as a vicious tool of racial control in the South after the Civil War. Lynchings were violent and public events designed to terrorize all Black people in order to re-establish white supremacy and suppress Black civil rights.

This was not “frontier justice” carried out by a few vigilantes or extremists. Instead, many African Americans were tortured to death in front of picnicking spectators for things like bumping into a white person, wearing their military uniforms, or not using the appropriate title when addressing a white person.

Lynch mobs included elected officials and prominent citizens. White people were celebrated—not arrested—for torturing and killing Black people. Spectators bought body parts as souvenirs and posed with hanging corpses for picture postcards to mail to their loved ones.

EJI has documented 4,084 racial terror lynchings in 12 Southern states between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950, which is at least 800 more lynchings in these states than previously reported. EJI has also documented more than 300 racial terror lynchings in other states during this time period. In addition, for all the documented lynchings covered in newspaper reports, many racial terror lynchings went unreported and their victims remain unknown.

Lynching shaped the geographic, political, social, and economic conditions that African Americans experience today. Critically, racial terror lynching reinforced the belief that Black people are inherently guilty and dangerous. That belief underlies the racial inequality in our criminal justice system today. Mass incarceration, racially biased capital punishment, excessive and disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color reveal problems in American society that were shaped by the terror era.

EJI believes it is critically important to confront America’s history of racial terror lynching. Our Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and creating a national memorial that acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

/

Howard University students protest outside the National Crime Conference in Washington, D.C., 1934.

Bettmann/Getty Images

/

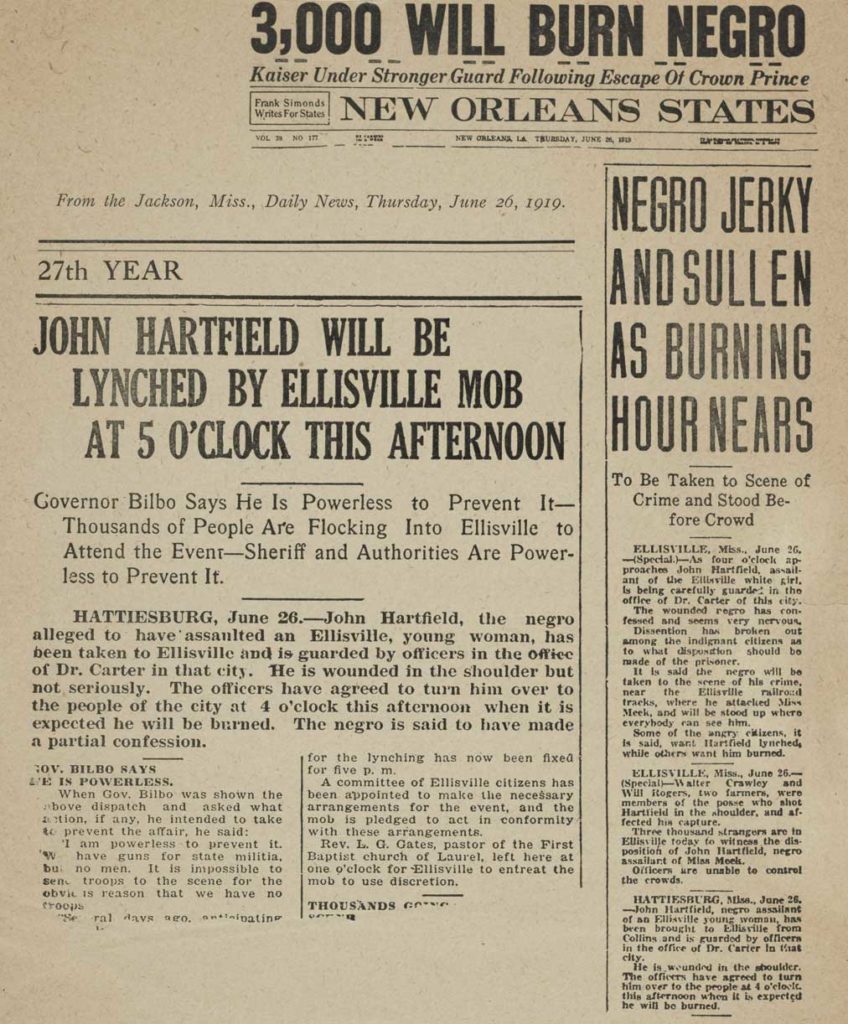

Mamie Lang Kirkland was seven when her family fled Ellisville, Mississippi, because her father and his friend, John Hartfield, were threatened by a lynch mob.

/

John Hartfield later returned to Ellisville, Mississippi, and was lynched before a crowd of 10,000 men, women, and children who traveled from across the state to watch.

/

Lynching victims George Dorsey and Dorothy Dorsey Malcolm are buried by the Black community, Monroe, Georgia, 1946. Mr. Dorsey, a World War II veteran who had served in the Pacific for five years, had been home for only nine months. Black veterans were targeted for racial terror.

Bettmann/Getty Images

/

On August 7, 1930, a large white mob in Marion, Indiana, beat and hanged 19-year-olds Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. EJI has documented more than 300 racial terror lynchings of Black people that took place outside the South.

Bettmann/Getty Images

/

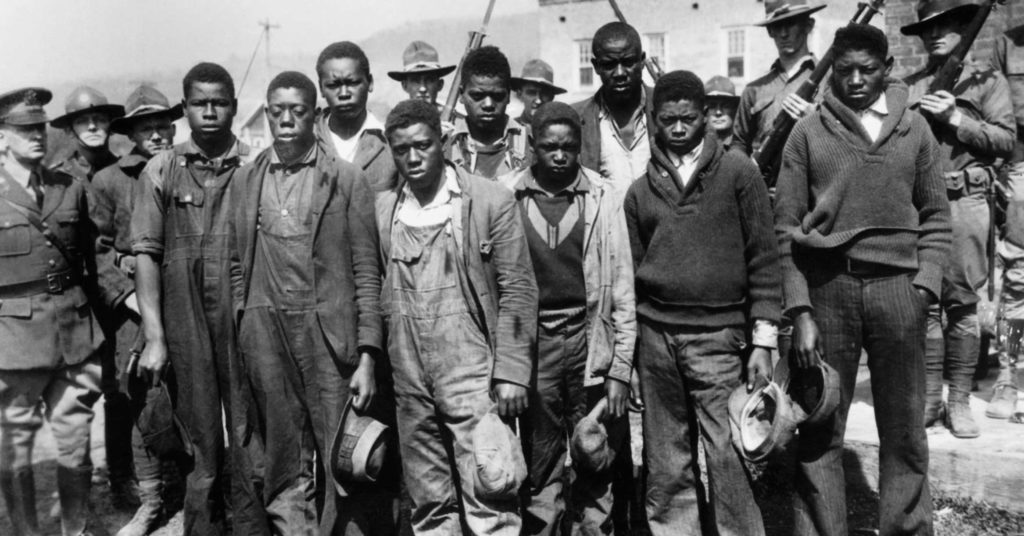

Nine young African Americans charged with raping two white women in Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931, were convicted by all-white, all male juries within two days as mobs converged outside; all but the youngest were sentenced to death. The death penalty is a “direct descendant of lynching.”

In response to demands for equal rights, millions of white Americans made clear their determined, unwavering, and committed opposition to racial equality, integration, and civil rights.

The story of the American civil rights movement is incomplete. We appropriately honor the activists who bravely challenged segregation, but we don’t talk about the widespread and violent opposition to racial equality.

Opposition to civil rights and racial equality was a mass movement. Most white Americans, especially in the South, supported segregation. Millions of white parents voted to close and defund public schools, transferred their children to private, white-only schools, and harassed and violently attacked Black students while their own children watched or participated.

Over the last 50 years, our political, social, and cultural institutions embraced elected officials, journalists, and white leaders who espoused racist ideas and supported white supremacy. White segregationists were not banished—they were elected and re-elected to prominent offices for decades after the civil rights movement.

Today more than ever, we need to acknowledge that most white Americans supported segregation—only a small minority of white Americans actively dissented from this widespread opposition to civil rights.

EJI’s online experience and our Legacy Museum use video footage from the segregation era to show how millions of white Americans arrested, beat, bombed, and terrorized civil rights demonstrators, including children. We profile the senators, governors, judges, writers, and ministers who led the movement to maintain segregation. And we expose the use of Confederate iconography to rally the opposition to racial equality with an interactive map showing thousands of Confederate monuments that were erected to maintain white supremacy long after the Civil War.

/

Young children wave Confederate flags at a White Citizens’ Council meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana, on November 16, 1960.

Bettman/Getty Images

/

Teenage girls scream obscenities at Black students entering their high school in Montgomery, Alabama.

Flip Schulke/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

/

After Brown v. Board of Education, many states authorized the closing of public schools to avoid integration.

Flip Schulke/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

/

White landowners in the South evicted thousands of African American sharecroppers who engaged in activism during the Civil Rights Movement.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

/

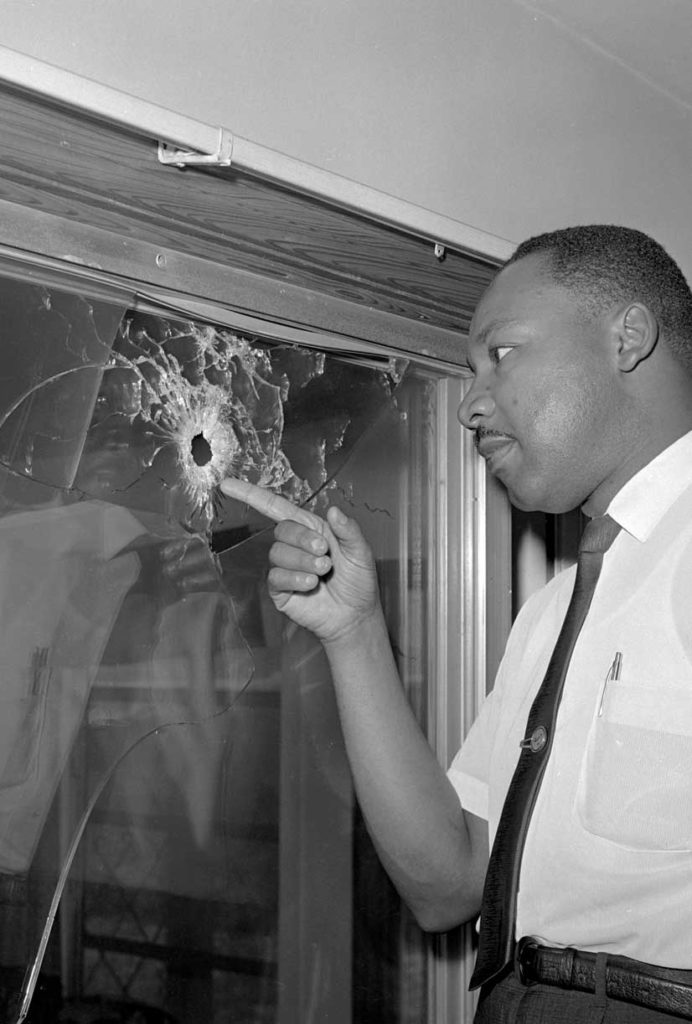

During anti-segregation demonstrations and marches in St. Augustine, Florida, more than 200 white residents chased and beat protestors, injuring 50 and sending 15 to the hospital. Dr. King inspects a bullet hole in the glass door of his rented house in St. Augustine on June 5, 1964.

AP

/

Officials who opposed civil rights systematically and strategically framed their rhetoric as “calls for law and order, arguing that Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of civil disobedience was a leading cause of crime.”

Spider Martin/Birmingham News

/

A large crowd gathers in South Boston to protest federal busing orders on September 12, 1974. A 2016 poll reported 38% of white Americans agreed the nation has already made the changes necessary to achieve equal rights while only 8% of Black Americans said the same.

Spencer Grant/GettyRacial disparities in our criminal justice system are a legacy of our history of racial injustice.

Black men are nearly six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men; Latino men are nearly three times as likely. Native Americans are incarcerated at more than twice the rate of white Americans.1 Jennifer Bronson, Ph.D., and E. Ann Carson, Ph.D., “Prisoners in 2017,” Bureau of Justice Statistics (April 2019). The Bureau of Justice Statistics projected in 2001 that one of every three Black boys and one of six Latino boys born that year would go to jail or prison if trends continued.

These racial disparities are rooted in a narrative of racial difference—the belief that Black people were inferior—that was created to justify the enslavement of Black people. That belief survived the formal abolition of slavery and evolved to include the belief that Black people are dangerous criminals.

During the decades of racial terror lynchings that followed enslavement, white people defended the torture and murder of Black people as necessary to protect their property, families, and way of life from Black “criminals.”

The presumption of guilt and dangerousness assigned to African Americans has made minority communities particularly vulnerable to the unfair administration of criminal justice. Numerous studies have demonstrated that white people have strong unconscious associations between Blackness and criminality.2 For example, Jennifer L. Eberhardt et al, “Seeing Black: Race, Crime, and Visual Processing,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (2004). Implicit biases have been shown to affect policing and all aspects of the criminal justice system.

So deeply entrenched is the presumption that people of color are dangerous and guilty that studies have found that Americans’ support for harsh criminal justice policies correlated with how many African Americans they believed were in prison: the more Black people they believed were incarcerated, the more they supported aggressive policing tactics and excessively punitive sentencing laws.3 Rebecca C. Hetey & Jennifer L. Eberhardt, “Racial Disparities in Incarceration Increase Acceptance of Punitive Policies,” Psychological Science (Aug. 5, 2014).

Understanding how today’s criminal justice crisis is rooted in our country’s history of racial injustice requires truthfully facing that history and its legacy. EJI is challenging the presumption of guilt and dangerousness in our work inside and outside the courtroom to reform the criminal justice system.

/

By criminalizing civil rights activists, opponents of civil rights shifted the public debate from segregation to crime.

Charles Moore/Getty Images

/

All of the 13- and 14-year-olds condemned to die in prison for nonhomicide offenses were children of color.

Richard Ross

/

Walter McMillian was wrongly sentenced to death for murder of a white woman despite alibi testimony from dozens of Black people.

Bernard Troncale

/

Compared to white students, Black students are 3.8 times as likely to be suspended and 2.2 times as likely to be referred to law enforcement.

Justin Bonaparte/Getty Images

/

The failure to hold police officers accountable perpetuates the national tolerance for violence against people of color.

Reuters/Jonathan Backman

/

The presumption of guilt and dangerousness contributes to negative outcomes in education, juvenile justice, and child welfare for Black girls as young as five.

John EarleEJI is engaging with communities and encouraging all Americans to confront our history of racial injustice and its legacy.