Prison guards have used dogs to attack nearly 300 people in state custody—and more than a dozen prison employees—over the past six years, leaving many permanently disabled, an Insider investigation revealed.

Insider used public records requests, court documents, medical records, and interviews with dozens of bite victims to document at least 295 incidents in which attack-trained dogs bit incarcerated people during the six-year period from 2017 to 2022.

During that period, handlers used attack-trained dogs against people incarcerated in at least 23 prisons in eight states, Insider found.

With 271 of the 295 documented attacks, Virginia is by far the leading user of prison attack dogs. In that state’s six high-security prisons, Insider found that attack-trained dogs are deployed against incarcerated people as a routine use of force.

Prison officials told Insider that attack-trained dogs make prisons safer, but no studies support that claim.

And the dogs are so aggressive that they bit correctional officers or other prison staff at least 13 times between 2017 and 2022, sometimes causing injuries so severe that emergency surgery was required.

“A dog is a loaded pistol,” Carlos Garcia, executive director of Arizona’s correctional officers union and a former canine officer in Arizona prisons, told Insider.

And like a loaded pistol, former Virginia corrections officer Brian Mitchell told Insider, using attack dogs inside the crowded, confined spaces found in U.S. prisons is dangerous for everyone who lives and works there. “The challenge is, in the facilities, especially in the stairwells, it’s a very tight place,” he said. “Everybody’s packed in there. The chances of someone getting bit are really high.”

Indeed, Insider reported that the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined Iowa’s Department of Corrections in 2018 for dangerous working conditions after inspectors found its patrol dogs—which had bitten incarcerated people, corrections staff, and their own handlers—were inadequately trained. As a result, OSHA’s report said, “the likelihood of officer injury from security animals is significantly increased.”

Simply witnessing a dog attack can result in severe and lasting trauma for incarcerated people and prison staff as well, Mr. Mitchell told Insider. “The screaming, the fighting, the blood,” he said. “It’s just not something you forget.”

Victims of attacks by prison patrol dogs suffered not only trauma but deep puncture wounds, lacerations with torn edges, and crush injuries to muscle, nerves, and bones from the pressure of the dog’s bite, which can puncture sheet metal. Many victims are permanently disabled or disfigured.

In at least 18 incidents, medical records showed that bite victims in Virginia were wounded so severely they had to be transferred to outside hospitals to be treated for crush injuries, extensive muscle and tissue damage, or septic infections.

Many victims were bitten on the neck, head, or torso—locations that indicate they may have been lying on the ground when they were attacked, Insider reported. Indeed, several victims told Insider they were compliant, on the ground in handcuffs or leg shackles, when they were attacked.

Rooted in a History of Racial Injustice

Insider identified eight Black men who said prison guards called them the n-word or used other racist language during or immediately after the dog attacks.

Linwood Mathias suffered permanent injuries during a dog attack at Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison in 2017. He told Insider that he is haunted by the memory of the dog’s handler yelling racial slurs during the attack. “Get ’em, boy!” he yelled. “Get that n—.”

When Mr. Mathias returned to Red Onion after 42 stitches and three surgeries over 13 days in a nearby hospital, another corrections officer told him, “I wish I could tie you to my bumper and drag you down the street.”

Some perpetrators of racial terror lynchings did exactly that—chaining or tying their victims’ corpses to cars and dragging them through Black neighborhoods to terrorize the entire Black community.

Michael Watson told Insider that the prison guard who used his dog to brutally attack and severely wound him at Red Onion in 2020 later told him that his dog “loves dark meat.”

Insider reported that an investigation by a state government agency found that corrections officers at Virginia’s Wallen Ridge prison had used racist slurs against incarcerated men and taunted them with songs about lynching.

“Yo, Black boy, you in the wrong place,” one guard told a Black prisoner. “This is white man’s country.”

Enslavers used dogs to track, attack, and sometimes even kill Black people who escaped from labor camps in the American South, Tyler Parry, an assistant professor of African American and African diaspora studies at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, told Insider.

Ever since, attack-trained dogs have been used as a form of “racialized terror” to violently enforce white supremacy, Prof. Parry said.

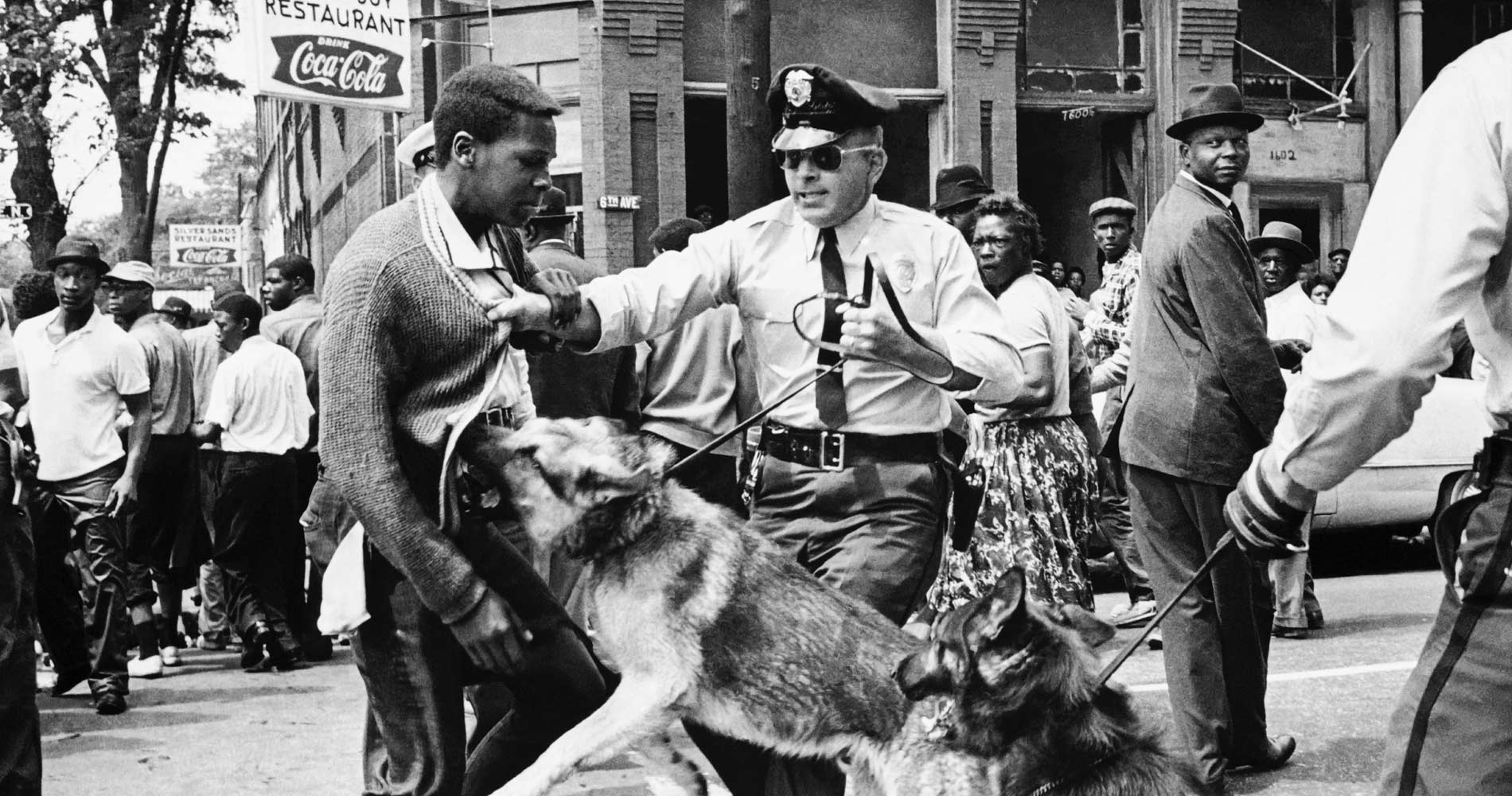

In 1963, white police officers in Birmingham, Alabama, ordered attack-trained dogs to bite Black children protesting against racial segregation. Photo by Bill Hudson.

“To Terrify and Intimidate”

Prison patrol dogs are used in tight, enclosed spaces, where their aggressive barking and lunging “is intended to terrify and intimidate,” according to Human Rights Watch, which describes the use of attack dogs inside prisons as a human rights violation.

Insider’s investigation revealed a direct connection between attack-trained dogs in U.S. prisons and the universally condemned human rights abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in 2003: all eight corrections experts who oversaw construction and trained staff at Abu Ghraib had earlier started, expanded, or administered programs that authorized the use of prison attack dogs in New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

“A dog going into a cell for the purpose of disarming someone or forcing compliance, to me, is a human-rights violation,” Kathleen Dennehy, former corrections commissioner in Massachusetts, told Insider. “The potential is there to do some serious injury.”

She banned the use of attack dogs in the state’s prisons in 2006. “I didn’t see any instances where we should be sending dogs in to potentially rip flesh off of inmates,” she said.

That same year, Dora Schriro, the director of the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reentry from 2003 to 2009, discontinued the use of attack-trained patrol dogs in Arizona prisons. “The idea that you would have to revert to the dog, particularly one that’s trained to attack, is beyond extreme,” she said.

But both states later reintroduced attack dogs.

Today, Insider reports that 12 states authorize the use of attack-trained dogs against people in state custody.