Investigations by the Justice Department and the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations found that, due to a change in reporting requirements, deaths in custody reported to the federal government have been significantly undercounted since 2019.

In announcing the findings, subcommittee chair Sen. Jon Ossoffsaid in a statement, “[W]hat the United States is allowing to happen on our watch in prisons, jails, and detention centers nationwide is a moral disgrace.”

The Death in Custody Reporting Act requires the Justice Department to collect information about people who die while in the custody of local, state, or federal authorities.

The law, which passed with broad bipartisan support in 2000 and again in 2013, was intended to bring a “new level of accountability to our Nation’s correctional institutions” and to “provide openness in government [and] bolster public confidence and trust in our judicial system.”

The Justice Department’s primary statistical agency, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, successfully collected this information from local jails and state and federal corrections systems for nearly 20 years.

But starting in October 2019, the Trump administration shifted responsibility for data collection to the Bureau of Justice Assistance—which provides training and technical assistance and distributes federal criminal justice grant money to state and local law enforcement agencies—and barred the agency from confirming the accuracy of data reported by states by checking it against public data sources or intervening in state data collection plans.

As a result, the subcommittee found, nearly a thousand deaths in custody in 2021 were not counted. The Appeal estimates that more than 5,000 deaths in the past three years were not counted.

The failure to collect accurate data for the past three years represents a “missed opportunity to prevent avoidable deaths,” the subcommittee observed, and it prevents both the government and the public from learning what happens to incarcerated people.

The subcommittee found that journalists and nonprofits collected more accurate and complete information on deaths in custody than BJA did. For example, BJA failed to identify two-thirds of arrest-related deaths identified by The Washington Post and the nonprofit Mapping Police Violence.

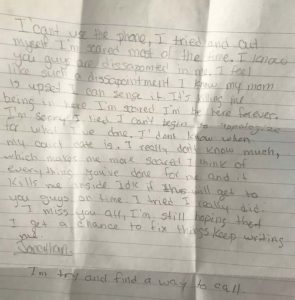

The subcommittee emphasized that accurate and complete data is critical to addressing the “urgent humanitarian crisis ongoing behind bars across the country.” It illustrated this crisis through the statements of witnesses who testified about family members who died in custody and through the writings and voices of those who died.

These examples include the February 2017 death of Jonathan Fano, who died by suicide after he was denied psychotropic medications while being held in custody at Louisiana’s East Baton Rouge Parish Prison awaiting adjudication of misdemeanor charges.

Letter from Jonathan Fano to Vanessa Fano, January 2017.

In another example, a man who died of heart failure in a Georgia detention center after being denied medical attention for weeks had told his mother he was coughing up blood and needed to go to the hospital. He died days after telling his mom, “I’m going to die in here.”

At tomorrow’s hearing I will release the findings from our 10-month bipartisan investigation of deaths in America’s prisons and jails. pic.twitter.com/Js3MPRfVTJ

— Jon Ossoff (@ossoff) September 19, 2022