As the nation contemplates the meaning of politically motivated violence, insurrection, and resistance to leaders elected to advance civil rights, it is useful to remember that in 1894, former Confederates in North Carolina lost governing power to an interracial political coalition. Four years later, they successfully carried out an insurrection against the duly elected government and murdered as many as 100 Black people.

Reconstruction in America and Wilmington

The 1898 coup in Wilmington, North Carolina, was an attempt to extend the racial order of enslavement into the post-emancipation era and maintain white supremacy.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, a 12-year period of Reconstruction began. During this time, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution were passed in order to create and strengthen Black citizenship.

The Fifteenth Amendment and federal laws requiring states to respect the voting rights of Black men enabled unprecedented numbers of African Americans to cast votes and hold elected office in the South. Black voters overwhelmingly supported candidates who were allied with the vision of President Abraham Lincoln and other leaders who advocated for Black civil rights.

Black political participation flourished during Reconstruction. For the first time throughout the country and in former slaveholding states, Black men were elected to office by their communities, who hoped they would implement meaningful reforms.

White Southerners bitterly resented Black voters’ growing political influence after the Civil War, which they saw as an obstacle to restoring their self-governance, and they blamed Black voters for white supremacist candidates’ repeated losses.

In his 1867 annual message to Congress, President Andrew Johnson declared that Black Americans had “less capacity for government than any other race of people.” They would “relapse into barbarism” if left to their own devices, he said, and giving them voting rights would result in “a tyranny such as this continent has never yet witnessed.” President Johnson also pushed to pardon former Confederates in exchange for their pledged loyalty to the Union.

This rhetoric and behavior from the president empowered white people to destroy politically-empowered Black voting blocs, especially in the South where the vast majority of African Americans lived.

Violence against newly freed Black people spread throughout the former Confederate states during Reconstruction, often in response to political organizing or exercising basic rights. EJI’s Reconstruction in America report documents dozens of massacres against Black people, including in New Orleans and Eufaula, Alabama, in 1868 and Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1874.

Due to Black political organizing and participation in Wilmington, African American political and economic prospects improved during Reconstruction and after its official end in 1877. By the 1890s, Wilmington was home to a thriving African American community composed of formerly enslaved Black people who entered Wilmington’s workforce and economy as skilled seamen, artisans, professionals, and government employees. By 1897, over one thousand African Americans owned property in the city. African American churches, schools, and cultural organizations flourished.

These gains were threatening to white supremacists, who rejected the idea of Black political and economic independence. Wilmington’s white elites, including elected officials and business leaders, sought to reestablish their local dominance, once enforced through enslavement but now achievable through political violence and racial terror. As was true throughout the South, Black people in Wilmington had no federal protection and were at the mercy of the same white officials who waged a war to keep them in bondage.

The Campaign to Undermine Democracy

For months ahead of the 1898 election, a coalition of political leaders, media outlets, and white supremacist groups conspired to enact their agenda and win at all costs. In March, Furnifold Simmons, a leading politician in the party championing white domination, developed a strategy to undermine the outcome of the November election across North Carolina. He called for an organized coalition of “men who could write, men who could speak, and men who could ride” to use “the unification of newspapers, traveling campaign speakers, and violent bands of men” to restore the rule of white supremacy. Wilmington became a focal point for Simmons’s campaign.

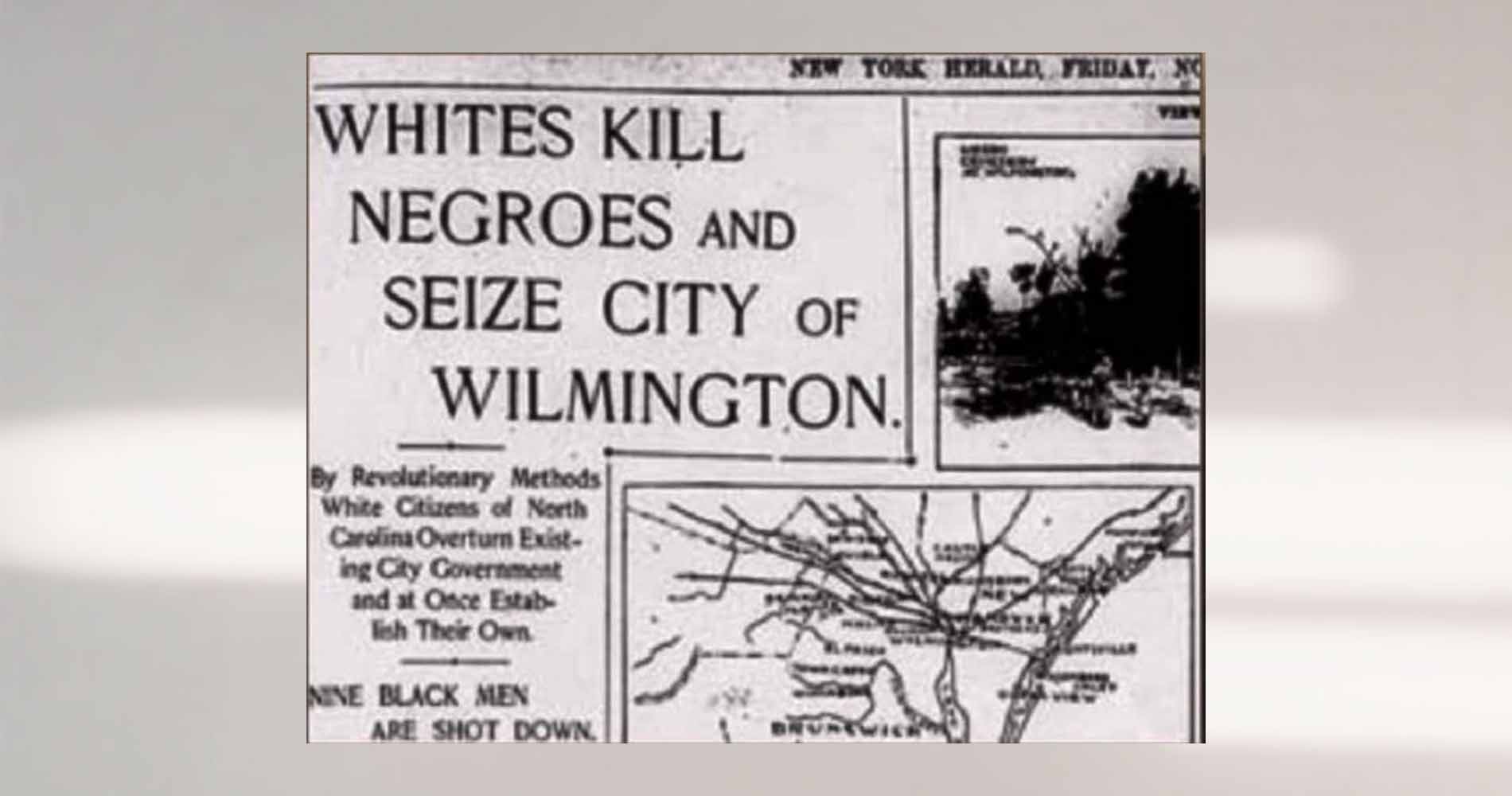

The first tactic—writing—involved working with the press to spread false propaganda about the upcoming election. Former Confederates sought to undermine the interracial governing coalition by arguing that Black officeholders were corrupt and unable to reduce crime or manage city services effectively. They ran op-eds, reports, and cartoons that stoked white fear by suggesting that Black people were inherently dangerous. Newspaper headlines explicitly called for “White Supremacy” and cartoons about the threat of “Negro rule” were commonplace.

Many white-owned newspapers willingly propagated these hostile narratives of racial difference. The dominant media narrative encouraged suspicion of Black people and created an environment of hostility, setting the stage for one of the nation’s most violent massacres and its only successful political coup.

The second tactic was speaking. Party leaders like Alfred Moore Waddell gave incendiary speeches in settings akin to contemporary political rallies to stir racial resentment. Weeks before the massacre began, Waddell gave a speech in which he stated that if violence erupted, he “trust[ed] that it [would] be rigidly and fearlessly performed.” He concluded by encouraging white people to “choke the current of the Cape Fear with [Black] carcasses” in order to win the election. This speech and others by elected officials who supported white supremacy stoked violence in the white community.

Riding—the third campaign tactic—involved intimidation by white supremacist groups. The White Government Union, a secret white supremacist political club, registered white voters and spread propaganda ahead of the 1898 election. The Union also had a paramilitary arm known as the Red Shirts, who were similar to the Ku Klux Klan. But rather than wear hoods and robes to hide their identities, Red Shirt members wore bright red tunics during their rallies and terror campaigns.

Both the White Government Union and the Red Shirts held armed marches through public areas and Black communities to intimidate African Americans leading up to election day. Party officials and businessmen sought to maintain white dominance through political and legal means, while members of the White Government Union and the Red Shirts worked alongside them with more direct tactics including intimidation, violence, and ultimately, bloodshed.

Despite the threats of violence surrounding the election, more Black residents of Wilmington registered to vote in the election than white residents. African Americans remained determined to exercise their right to participate in democracy.

The Wilmington Massacre: Election Day Racial Terrorism

On Election Day, November 8, 1898, a months-long white supremacist agenda of voter suppression culminated in violence and fraud at the polls. Armed men patrolled Wilmington to intimidate African American voters and their allies. White supremacists threatened poll workers as they counted ballots, and in at least one precinct, stuffed ballot boxes to secure their party’s victory. Less than 72 hours later, the insurrection would be complete.

The day after the election, white citizens held a mass meeting at the New Hanover County Courthouse. Alfred Moore Waddell and other leaders read and finalized the White Declaration of Independence—despite evidence that they had won the election. The declaration read: “We, the undersigned citizens of the City of Wilmington and County of New Hanover, do hereby declare that we will no longer be ruled, and will never again be ruled by men of African origin.” The declaration demanded the resignation of duly elected local officials, including the mayor and police chief.

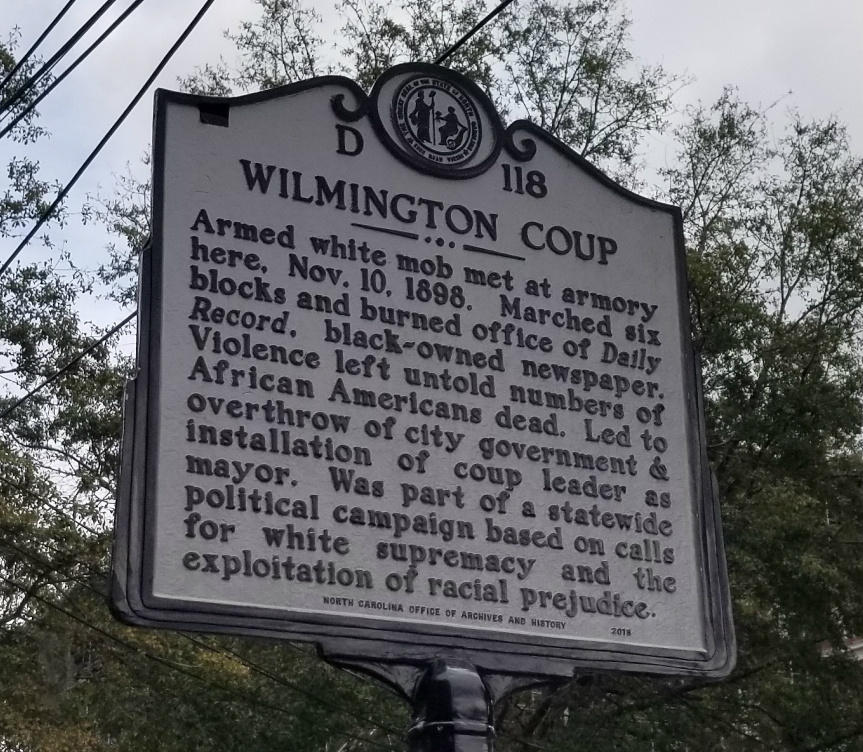

That evening, the white leaders who co-signed the declaration met with the Committee of Colored Citizens (CCC), representatives of the African American community, to issue their demands. The CCC were ordered to reply to the demands by 7:30 the next morning. At around 8 a.m., Waddell and a mob of white men impatient to hear from the CCC assembled at the armory building of the Wilmington Light Infantry, a local militia unit.

They marched from Market Street to Seventh Street to The Daily Record building, a Black-owned newspaper that became a target of the mob because it had openly challenged narratives of racial difference. When the mob reached the building, they broke in and set the Black media outlet ablaze. The mob then blocked the all-Black fire company that attempted to put out the flames.

The campaign of stoking white resentment was the kindling, and the burning of The Daily Record building was the final spark for the massacre and coup. Soon after the building burned, the mob took Wilmington by force.

From Thursday, November 10, until Saturday, November 12, mobs of up to 2,000 armed white men occupied the corner of Fourth and Harnett Streets. They unleashed terror, indiscriminately shooting at Black men, women, and children in the street. Black residents had no meaningful government protection. Contemporary estimates suggest anywhere from 30 to 100 Black people were killed during the massacre.

The Political Coup and Aftermath of the Massacre

While Black people were being massacred in the streets, a mob of over 100 white men occupied city hall and forced city officials under the threat of violence to resign from office on November 10. The white supremacists appointed Waddell, leader of the mob, as Wilmington’s new mayor.

The slate of men who supported the coup in Wilmington was re-elected to office in March 1899 by white Wilmington residents, making the event the first and only successful coup d’état in U.S. history.

In the weeks following the massacre, many African American political leaders and businessmen were banished from town. White allies of the Black community also became targets. Under order of the new white supremacist leaders, the Wilmington Light Infantry arrested political targets, detained them in jail, and upon release, demanded that they leave North Carolina and never return.

Traumatized Black families gathered their belongings and fled to cities in the North and West. The demographics of the U.S. were shaped by this era of racial terror, as African Americans left the South en masse following lynchings and ubiquitous violence. They traveled as refugees in their own country searching for safety and freedom.

Meanwhile, white people in Wilmington and across the state celebrated in the aftermath of the massacre. On Sunday, November 13, white ministers gave sermons praising the violence. One minister preached that the “whites were doing God’s service.” Parades and celebratory gatherings were held in Wilmington and Raleigh. White communities created an atmosphere of terror for African Americans by celebrating the racial violence.

President William McKinley declined to intervene or provide assistance to Wilmington’s Black residents. Members of the mob and elected leaders alike acted with total impunity. In the end, no one was held accountable.

Photo taken on January 6, 2021, during the violent riot at the U.S. Capitol.