Nathan Bryan Whitfield enslaved hundreds of men, women, and children over four decades at his family’s plantations in Alabama and North Carolina. He not only forced them to do the backbreaking labor of planting and picking cotton, but he also made scores of them walk 700 miles from North Carolina to Demopolis, Alabama, where white enslavers in the 1830s were, in his words, “getting rich rapidly.”

He named his 1,280-acre Demopolis plantation Gaineswood. In addition to stooping over rows of cotton amid sweltering heat, snakes, and insects, people enslaved at Gaineswood were forced to do the dangerous underground work of excavating a mile-long drainage canal. They were also forced to dig an artificial lake for the Whitfield family’s enjoyment and construct the Greek columns that framed the Whitfields’ opulent home. They cooked and served the Whitfields’ meals, scrubbed their floors, cared for their children, and emptied their slop jars.

Mr. Whitfield used his vast wealth, generated by two plantations in Alabama and one in North Carolina, to support the Confederacy. He turned Gaineswood into a temporary headquarters for one of its generals. He made enslaved people build fortifications around Demopolis to stop “the Abolitionists,” as he referred to advancing Union troops.

Today, a display at Gaineswood, which is now a state-owned museum, calls Mr. Whitfield “The Jefferson of Alabama.” Gaineswood’s website calls him “a Renaissance man.” So does the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The museum website gives no hint that he was a large-scale enslaver, saying only that Gaineswood’s builders “included skilled African Americans (both enslaved and free).” The existing portrayals of Mr. Whitfield focus on his wealth, architectural ingenuity, and ambition—a man who set out to make his drawing room “the most splendid room in Alabama.”

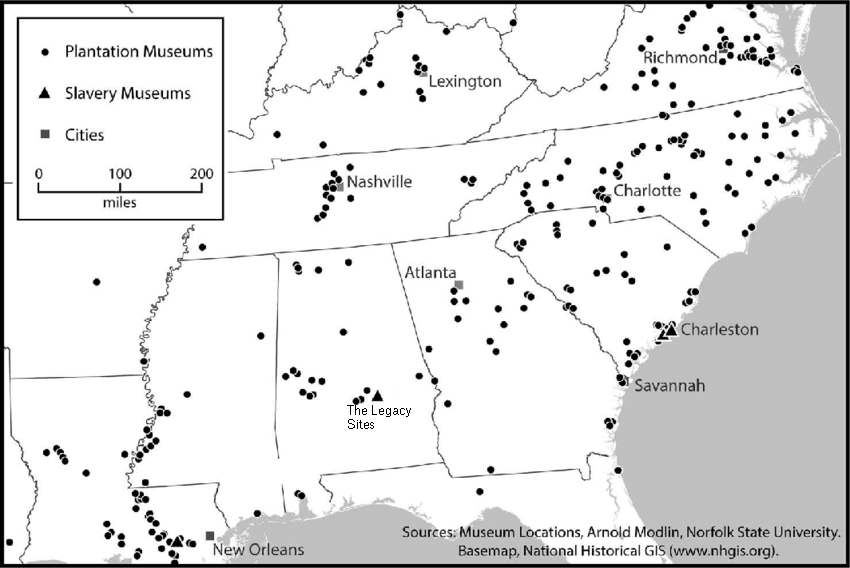

Gaineswood is one of about 375 publicly or privately owned plantation sites scattered across 19 states in the U.S. All told, they draw millions of visitors every year. In the Charleston area alone, heavily marketed sites like Boone Hall Plantation & Gardens, Magnolia Plantation & Gardens, and Middleton Place attract more than half a million visitors a year.

Compiled by Stephen P. Hanna, published in Potter, Hanna et al, Remembering Enslavement: Reassembling the Southern Plantation Museum (2022), with EJI’s Legacy Sites in Montgomery, Alabama, added.

Today’s plantation landscape reflects the nation’s reluctance to confront the true history of slavery and its legacy of racial injustice. Amy Potter, who studies plantation tourism and is a professor at Georgia Southern University, says telling the truth about this history is a moral imperative, especially now, when there is a movement across the country to limit the teaching of our history. A “plantation edutainment complex” has emerged, according to a 2018 National Science Foundation-funded study of 15 plantations in Virginia, South Carolina, and Louisiana led by Ms. Potter. Commercialized plantation sites tout luxury inns, Halloween ghost tours, wine and bourbon tastings, strawberry festivals, and plantation weddings, their biggest moneymaker. The owner of one site, Houmas House, transformed a Louisiana sugar cane plantation, where 800 Black people were enslaved, into what he calls a “Disneyland for adults.” All the entertainment, says Ms. Potter, undercuts efforts to tell truthful history.

Houmas House Plantation near New Orleans

Canadian documentary filmmakers Alex Bezeau and Lauren Cudmore—Cudmore is also an archaeologist and public historian—reached similar conclusions from interviews conducted in 2023 at 20 U.S. plantation sites for their forthcoming documentary, Vacation Plantation. One of those sites is Rosedown, a former Louisiana cotton plantation where hundreds of enslaved people were held in bondage and suffered under cruel working conditions. At Rosedown, now state-owned, staff have recently begun telling a piecemeal history of slavery, but the gardens and the restored big house remain the main attractions and “the entryway to telling the big story,” as Louisiana’s parks program manager Raymond Berthelet told the filmmakers.

Asked about the challenges of telling the slavery history truthfully, Mr. Berthelet voiced concern that if they do, families may choose not to visit the sites. Berthelet said, “If you say, ‘We’re doing a program on the enslaved,’ there is that factor—on a Saturday afternoon, do you take the wife and kids?…For a lot of folks, it might be a negative topic. It was a horrible institution, there’s no sugarcoating it.”

Tracing the Myth of “Moonlight and Magnolias”

Plantation tourism originated after the Civil War, when cash-strapped former enslavers began opening their opulent homes to paying visitors. By the early 20th century, plantations were tourist attractions that, like the film Gone with the Wind, glorified the Lost Cause myth of a South that fought the Civil War to preserve not slavery and white supremacy but a “genteel” way of life.

In this false narrative, white enslavers were always caring, and enslaved Black people were content and dependent. The “moonlight and magnolias” plantation experience, as it was called, gained popularity in the 1960s and ‘70s when many who opposed the civil rights movement wanted to indulge in fantasies of a South that never existed.

A Reckoning after Dylann Roof

Dylann Roof inside a dwelling at Boone Hall Plantation in Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina

Calls for truth-telling at plantations intensified after Dylann Roof’s 2015 massacre of nine Black people at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston. In the months before the killings, Mr. Roof, who espoused white supremacist views, visited four South Carolina plantations, taking selfies at slave dwellings and in front of a mansion.

Though plantations were places where enslaved people were tormented, could not legally marry, and Black families were torn apart, wedding promoters today connect these sites to visions of “love, laughter, and happily ever after,” as said on a sign at an Alabama antebellum plantation home that hosts weddings.

For years, many have campaigned against the plantation wedding industry. “Plantations are former forced labor camps,” a 2019 Color of Change petition said. “They are not party spaces.” The campaign gained momentum after the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

Several major wedding planning websites announced steps to limit the promotion of plantation weddings. The Knot International urged wedding venues to “avoid language that romanticizes the history of slavery” on its website. Zola pledged not to promote “any wedding venue with a history of slavery.” The New York Times stopped publishing announcements of weddings at plantations.

Yet people are still getting married at plantations. It is a multimillion-dollar industry. At Boone Hall, the minimum cost of one wedding, including rental fees, caterers, photographers, and other expenses, has been estimated at $25,000. Boone Hall has said it hosts an average of 130 weddings a year.

Many plantations are owned by the original owners’ descendants and still provide income and profit to families who gained wealth through enslaved labor. Advertisements rarely disclose this history and instead tout the spaces as idyllic and romantic.

Mixed messages on the plantations themselves abound. In South Carolina, Boone Hall houses a Black history exhibit in restored slave dwellings while also promoting weddings on the “historic Cotton Dock.” Middleton Place offers an extensively researched presentation on the more than 2,800 people enslaved by the Middleton family—and, for prospective brides and grooms, “an unforgettable setting for one-of-a-kind weddings,” with 10 locations on the former plantation to choose from.

Besides hosting weddings, Houmas House, on the Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, offers three restaurants, a bar, an inn, and tours of the house and gardens—but guides avoid mentioning the site’s history of mass enslavement. “If you want a tour of slavery,” owner Kevin Kelly told an interviewer in 2021, “you go someplace else.” Viking Cruises and two other cruise lines offer stops at the former plantation.

Mr. Kelly once staged a lavish “wedding” of his two dogs at Houmas House, with 2,000 invited guests. He has said that talking about the site’s enslavement history would be like “trying to tell the story at Disneyland of how poorly the employees at Disney are treated.”

Wrestling with the “Moral Imperative”

When it opened in April 2015 on James Island, just south of Charleston, McLeod Plantation Historic Site set itself apart from other plantation sites by centering the stories of enslaved people and their descendants. McLeod also promoted itself as a wedding venue, as a way to support the educational mission, according to the Charleston County Park & Recreation Commission, which owns and operates the site.

Instead, as Amy Potter found in her research, for many, weddings at McLeod undermined the “larger moral imperative” of the mission. In her 2022 book, Remembering Enslavement, Reassembling the Southern Plantation Museum, Ms. Potter quotes one interpreter at McLeod on the dissonance staff and visitors experienced in trying to focus on the suffering of enslaved people while hearing members of a bridal party preparing for a wedding:

People are downstairs reading these banners about slavery and asked to consider what their lives were like, what the lives of all the tenants, all the occupants of this house were. . . . And then there are six women up here giggling and spraying hairspray and playing music, and you can hear it all over the house. It’s unavoidable. So it’s disturbing.

That dissonance sharpened after the Charleston massacre. Dylann Roof, who had subscribed to the Lost Cause mythology, visited McLeod on its opening day, April 25, 2015—two months before he entered the church in Charleston and started shooting Black people praying at a Bible study group.

“[Dylann Roof] changed everything,” public historian Shawn Halifax, a former McLeod director of cultural interpretation, said at a 2020 International Coalition of Sites of Conscience webinar discussion about whether places that tell the history of atrocities should hold weddings and other events. “It changed our approach and our understanding of this site and the placement of historic context. It altered how we thought about the site and the kinds of activities that should be here.”

In 2019, after joining the Coalition of Sites of Conscience, Mr. Halifax said, McCleod announced it would stop hosting weddings (those already scheduled were grandfathered in).

The speaker who followed Mr. Halifax was Henrike Claussen, director of the Memoriam Nuremberg Trials. The Memoriam hosts an exhibition above the courtroom where, after World War II, Nazi leaders were tried for their crimes. It would be unthinkable to host weddings in such a space, Ms. Claussen said. “I’m sure there’s no one who would like to get married in front of [convicted Nazi war criminals] Göring and Hess and Streicher.”

Two young girls at The Oaks Plantation in Goose Creek, South Carolina, 1903

Confronting the Truth

There has been an effort to modify the narrative about slavery in some spaces. There is a section at Gaineswood titled “Contributions of Enslaved People” with descriptions of enslaved people doing work at the plantation. Yet, an annotated guide to the Whitfield papers that is displayed in the main exhibit room highlights correspondence between Mr. Whitfield and his agent involving an enslaved man. “William needed a doctor after a serious injury (his thigh bone came out),” the guide recounts, “but the doctor’s bill would be ‘worth more than the negro.’’’ Those five words, the guide says, “reveal that at the end of the day, Whitfield was making business decisions, not necessarily humanitarian [ones].”

Multiple people enslaved by the Whitfields risked their lives seeking freedom by escaping. Whitfield family papers reveal that men named Isaac and Dick escaped the Whitfields’ North Carolina plantation in 1826, but were captured 150 miles north—halfway to freedom. Also captured was Fanny, a woman who had escaped four months after Nathan Whitfield enslaved her.

Enslaved people’s escapes from plantations in Alabama’s Black Belt were so commonplace that a white resident of Jefferson, the town where the Whitfields had their second Alabama plantation, advertised himself in 1861 as a “negro hunter” equipped with a “pack of trained hounds.”

Since the end of the Civil War, many Americans have sought to romanticize and legitimate slavery. “There is no acceptable or humane way to torture someone in bondage, to commit mass murder or genocide, to engage in sexual assault and abusive violence. There is similarly no acceptable way to enslave another human being,” said EJI executive director Bryan Stevenson. “Confronting this reality is going to be essential in overcoming the legacy of slavery and the multiple ways it has fueled racial injustice that still persists. Recovering from horrific eras of extreme abuse requires transitional justice. Models exist in South Africa, Germany, and Rwanda.”

In thinking about how plantations tell the history of slavery, Amy Potter also points to Germany and its teaching of the Holocaust. “They’re openly talking about that history, engaging with that history,” she said. But many Americans still sugarcoat slavery or avoid the topic. “We ran from it and romanticized it,” she said. Plantations have become central to many of the distortions.