Community members gathered today in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, to dedicate a new historical marker in memory of Benjamin Hance, a 22-year-old Black man who was lynched by a white mob in Leonardtown on June 17, 1887. Members of the St. Mary’s County Museum Division in partnership with EJI installed the marker at the Old Jail Museum, located at 41625 Courthouse Road, which was the site where the mob abducted Mr. Hance from jail before hanging him to death at a nearby location.

Over a hundred community members attended the dedication ceremony to memorialize Mr. Hance, including representatives from local government, county institutions, schools, faith communities, and the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project. Students attending high school in St. Mary’s County also received scholarship awards for participating in the St. Mary’s County Just Society arts competition.

The Lynching of Benjamin Hance

At approximately 2 am on June 17, 1887, a white mob lynched Benjamin Hance, a 22-year-old African American resident of St. Mary’s County, at the intersection of Newtowne Neck Road and Macintosh Run. The previous month, while running an errand for his employer, Mr. Hance allegedly encountered a white woman named Alice Bailey. When Ms. Bailey later reported an assault, claiming that Mr. Hance made “an improper proposal” to her, he was taken into custody and placed in the Leonardtown Jail.

During this era, accusations that a Black man had assaulted a white woman regularly aroused mob violence and lynching. On June 17, a mob of white men came to the jail intent on lynching Mr. Hance. Battering down the jail doors with axes, the mob dragged him from his cell and carried him outside the jail. A white man who lived near the jail saw the mob abduct Mr. Hance. Rather than intervene, the man asked the mob to carry out the lynching elsewhere so as not to disturb his wife.

The mob took Mr. Hance two miles away and hanged him from a witch hazel tree. His body was later buried in the St. Aloysius Church Old Cemetery. Local law enforcement officials failed to indict, prosecute, or hold anyone accountable for the terror lynching, despite several mob members having been identified by county residents. The historical marker was erected to remember Benjamin Hance in support of justice for all.

St. Mary’s County Community Remembrance Project

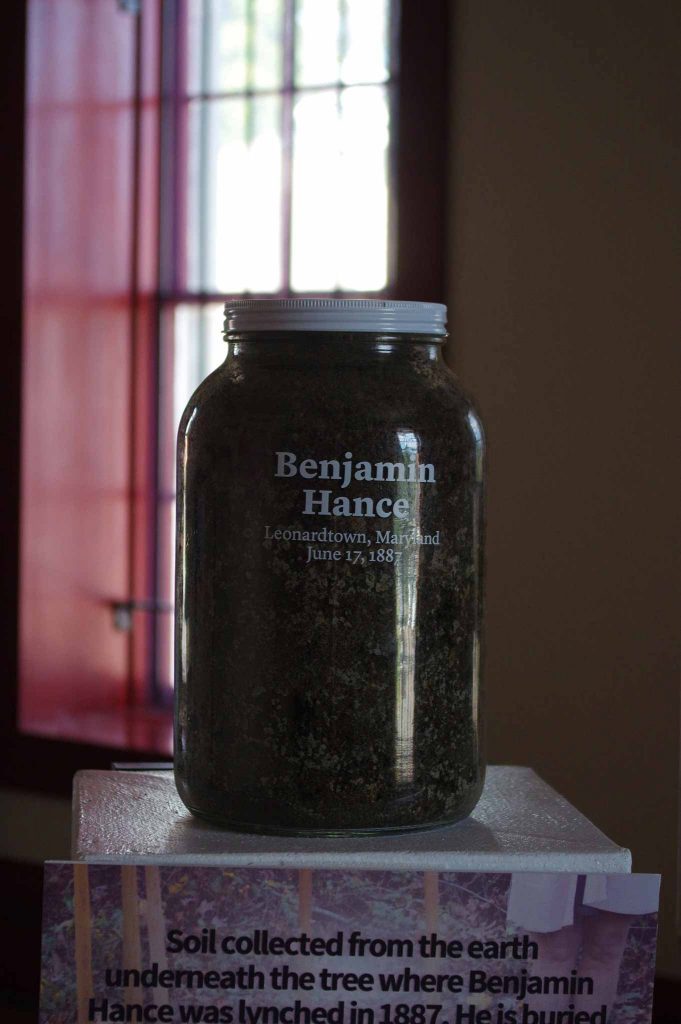

In 2019, St. Mary’s County Museum Division connected with other local partners to form a coalition in pursuit of memorializing the story of Benjamin Hance. On November 1, 2019, the coalition hosted a community soil collection event where dozens of community members gathered to learn more about Mr. Hance’s story and the legacy of his lynching. The soil collected was incorporated into a local exhibit in the Old Jail Museum in Leonardtown and a second jar of soil was sent to EJI to be featured in the Legacy Museum’s Soil Collection Exhibit.

The historical marker dedication was the recent culmination of the coalition’s efforts to have Mr. Hance’s story permanently built into the community. Sponsors and partners of the marker dedication included the Big Conversation Partnership, St. Mary’s County commissioners, the county bar association, Department of Recreation and Parks, county public library, Friends of the St. Clement’s Island and Piney Point Museums, the St. Mary’s County NAACP, the Unified Committee for Afro-American Contributions, and Leonardtown residents and community leaders. The coalition hopes to advance further conversations about equity and justice in Leonardtown and the county.

/

Attendees gather at the Old Jail Museum in Leonardtown to honor Benjamin Hance.

Ron Bailey

/

Dancers from St. Mary’s Ryken High School perform during the marker dedication ceremony.

Ron Bailey

/

Will Shwarz, President of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project, addresses ceremony attendees.

Michael Reid/Southern Maryland News

/

A jar with soil collected to memorialize Benjamin Hance.

Lynching in America

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. After slavery ended, many white people remained committed to racial hierarchy and used lethal violence and terror against Black communities to maintain a racial, economic, and social order that oppressed and marginalized Black people. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and created a legacy of injustice that can still be felt today.

Many African Americans were lynched after exercising their civil rights, defying racial social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or being accused of crimes, even when there was no evidence to support the accusation. Racial terror lynching was generally tolerated by law enforcement and elected officials who were often complicit in these tragedies. Denied equal protection under the law, lynching victims were regularly pulled from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or police custody by white mobs who faced no legal repercussions.

Nearly 25 percent of all lynchings, including the lynching of Benjamin Hance, were sparked by accusations of sexual assault by Black men against white women, at a time when such accusations extended to any action that could be interpreted as merely seeking contact with a white woman. Racial terror lynchings often included burnings and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands. In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South, never to return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Although many victims remain unknown, at least 40 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Maryland, including Mr. Hance’s lynching in St. Mary’s County.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching and advance honest conversation about the legacy of racial terror by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and inviting community members to visit the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, where the horrors of these racial injustices are acknowledged.

Through the Community Remembrance Project, EJI has joined with dozens of communities to install historical markers where the history of lynching is documented in our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face, from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, and police violence to the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that continues to burden people of color today.