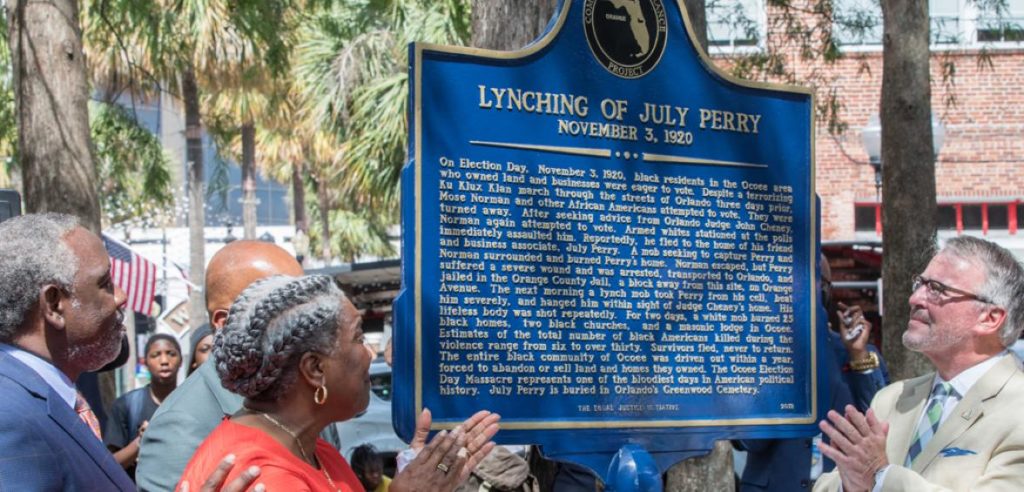

EJI staff joined hundreds of community members, including Mayor Buddy Dyer and Orange County Mayor Jerry L. Demings, in downtown Orlando on Friday for the unveiling of a historical marker honoring July Perry, who was lynched in a violent attack that began on Election Day 1920.

Mr. Perry’s descendants were recognized at the unveiling ceremony at Heritage Square, in front of the Orange County Regional History Center. After the ceremony, EJI director Bryan Stevenson spoke at the Orlando Public Library.

A local coalition led by the Truth and Justice Project of Orange County organized the marker installation in partnership with EJI. Sponsors of the unveiling event include Bridge the Gap Coalition, the City of Orlando, Orange County Government, the Orange County Public Library System, and the Orange County Regional History Center.

EJI announced the winners of our Racial Justice Essay Contest, who were awarded $6000 in scholarships. Evans High School senior Nabiha Nur won first place; in second place was Johana Dauphin, a junior at Boone High School; Ocoee High School seniors Dahila La Pommeray, Samantha Guerrier, and Siana Hayden won third, fourth, and fifth place, respectively.

The Lynching of July Perry

On Election Day, November 2, 1920, Black residents in the Ocoee area who owned land and businesses were eager to vote. Despite a terrorizing Ku Klux Klan march through the streets of Orlando three days earlier, Mose Norman and other African Americans attempted to vote. They were turned away.

After seeking advice from Orlando Judge John Cheney, Mr. Norman again attempted to vote. Armed white men stationed at the polls immediately assaulted him. He reportedly fled to the home of his friend and business associate, July Perry.

A mob seeking to capture Mr. Perry and Mr. Norman surrounded and burned Mr. Perry’s home. Mr. Norman escaped, but Mr. Perry was severely wounded. He was arrested, taken to Orlando, and locked in the Orange County Jail.

The next morning, a lynch mob took Mr. Perry from his cell, brutally beat him, and hanged him within sight of Judge Cheney’s home. His lifeless body was shot repeatedly.

Over the next two days, a white mob burned 25 Black homes, two Black churches, and a masonic lodge in Ocoee. Estimates of the total number of Black Americans killed during the violence range from six to over 30. Survivors fled, never to return. The entire Black community of Ocoee was driven out within a year, forced to abandon or sell land and homes they owned.

The Ocoee Election Day Massacre represents one of the bloodiest days in American political history. July Perry is buried in Orlando’s Greenwood Cemetery.

In the past, few public memorials have addressed the nation’s history of lynching, and most victims have never been publicly acknowledged. “Such acknowledgement is part of a path toward healing,” Amy Lalanne of the Truth and Justice Project said in a statement. “We are working to create a more hopeful, collaborative, and just society for every person in Orange County, Florida.”

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of its effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. EJI believes that by reckoning with the truth of the racial violence that has shaped our communities, community members can begin a necessary conversation that advances healing and reconciliation.

Lynching in America

Thousands of Black people were the victims of lynching and racial violence in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The lynching of African Americans during this era was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching was most prevalent in the South, including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. After the Civil War, violent resistance to equal rights for African Americans and an ideology of white supremacy led to violent abuse of racial minorities and decades of political, social, and economic exploitation.

In an expanded edition of Lynching in America, EJI also documented racial terrorism beyond Southern borders, detailing more than 300 lynchings of Black people in eight states with high lynching rates in the Midwest and the Upper South, including Oklahoma, Missouri, Illinois, West Virginia, Maryland, Kansas, Indiana, and Ohio.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many Black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known, but over 300 documented lynchings took place in Florida alone. Researchers estimate at least 33 in Orange County — the most lynchings of any county in the state.

/

Descendants of July Perry.

/

Hundreds of people gathered for the unveiling ceremony.

/

Orange County Mayor Jerry L. Demmings, Bryan Stevenson, Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer, and Aramis Ayala, State Attorney for Florida’s 9th Judicial Circuit.

/

Mr. Perry’s descendants and local officials applaud marker unveiling.