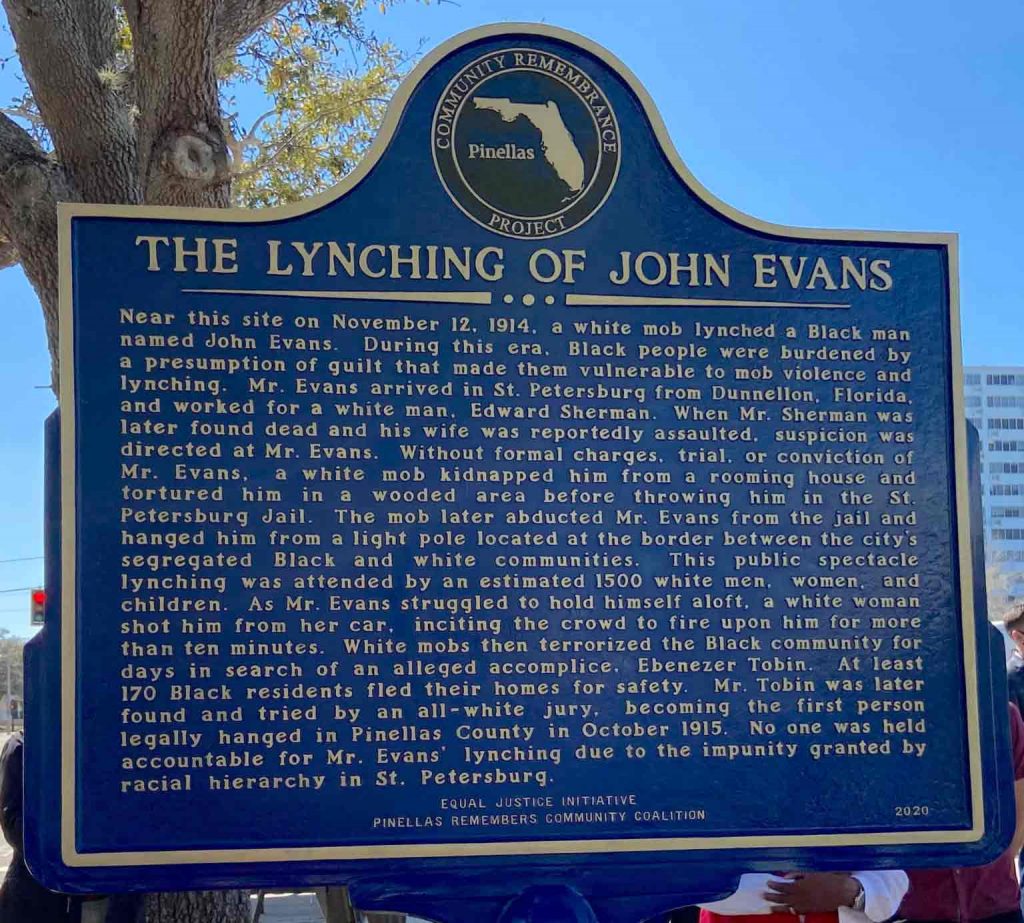

Pinellas Remembers, a Community Remembrance Project coalition, partnered with EJI to install a historical marker for John Evans, a Black man lynched in St. Petersburg, Florida, on November 12, 1914. The marker is located near the site of Mr. Evans’s lynching, at the intersection of Old Ninth Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Street) and Second Avenue South.

The historical marker was unveiled at a dedication ceremony on Tuesday, February 23. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, a small group of Pinellas County residents attended in person while other community members joined via online streaming and social media. Elected officials, faith leaders, and community activists offered remarks about the need to honor the life of John Evans and confront the community’s history of racial violence. Florida State Senator Darryl Rouson attended the dedication ceremony and encouraged the community to understand the purpose of the narrative marker. “Welcome to the memorialization of what should never happen again,” he said.

Mayor Rick Kriseman spoke to the role of local officials in confronting this history as well. “It is incumbent on us as city leaders to call out, not just the injustices of today but to recognize the horrors and injustices of the past as well,” he said.

Jacqueline Hubbard, co-chair of Pinellas Remembers, emphasized what the marker should symbolize to the community:

“It’s a powerful opportunity for the community to do some reflection,” said Kiara Boone, Deputy Director of Community Education at EJI. “Ultimately, it creates a symbolic reminder of the work that communities need to do going forward.”

Members of the Tampa Bay community are encouraged to visit the marker in St. Petersburg.

The Lynching of John Evans

On November 12, 1914, a white mob in St. Petersburg, Florida, lynched a Black man named John Evans. In the U.S., Black people have been burdened by a presumption of guilt that made them vulnerable to mob violence and lynching. John Evans had arrived in St. Petersburg from Dunnellon, Florida, and when his white employer was found dead, suspicion was directed at Mr. Evans. Without formal charges, trial, or conviction of Mr. Evans, a white mob kidnapped him from a rooming house and tortured him in a wooded area before throwing him into the St. Petersburg Jail. The mob later abducted Mr. Evans from the jail and hanged him from a light pole located at the border between the city’s segregated Black and white communities.

This public spectacle lynching was attended by an estimated 1,500 white men, women, and children. As Mr. Evans struggled to hold himself aloft, a white woman shot him from her car, inciting the crowd to fire upon him for more than 10 minutes. White mobs then terrorized the Black community for days in search of an alleged accomplice, Ebenezer Tobin. At least 170 Black residents fled their homes for safety. Mr. Tobin was later found and tried by an all-white jury, becoming the first person legally hanged in Pinellas County in October 1915.

No one was held accountable for Mr. Evans’s lynching due to the impunity granted by racial hierarchy in St. Petersburg. Of the more than 316 racial terror lynchings EJI has documented in Florida between 1877 and 1950, at least three took place in Pinellas County, including John Thomas on December 25, 1905, and Parker Watson on May 9, 1926.

Pinellas Remembers Community Remembrance Project

Pinellas Remembers began organizing together after visiting EJI’s Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opened in April 2018. The coalition is composed of dozens of organizations and individuals who are committed to racial justice. The group subsequently organized trips for others to experience the sites in Montgomery.

In July 2020, coalition co-chairs Jacqueline Hubbard (President of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History St. Petersburg, FL) and Gwendolyn Reese (President of the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, FL, Inc.) went before the City of St. Petersburg Community Planning and Preservation Commission seeking approval to place the historical marker on city property. After the presentation and public comment, the city unanimously approved the marker project. Commissioner Will Michaels said, “These markers are extremely important because they help to tell a story, to make people aware and I think most people in our city are really not aware of the John Evans lynching and all that is associated with it.”

In February 2021, the coalition partnered with Eckerd College, Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, and the Sarasota Manatee Community Remembrance Project to host a virtual panel about the history of racial terror lynching in Florida’s Tampa Bay region.

Pinellas Remembers also worked with EJI to launch a racial justice essay contest for local public high school students this spring semester. Students are asked to connect the history of racial injustice to contemporary issues for the opportunity to win scholarship funds. The Tampa Bay Rays Foundation generously donated to support a local arts contest in which students will use visual and performing arts to confront racial history. Each student will have their work honored with prizes and a public showcase.

/

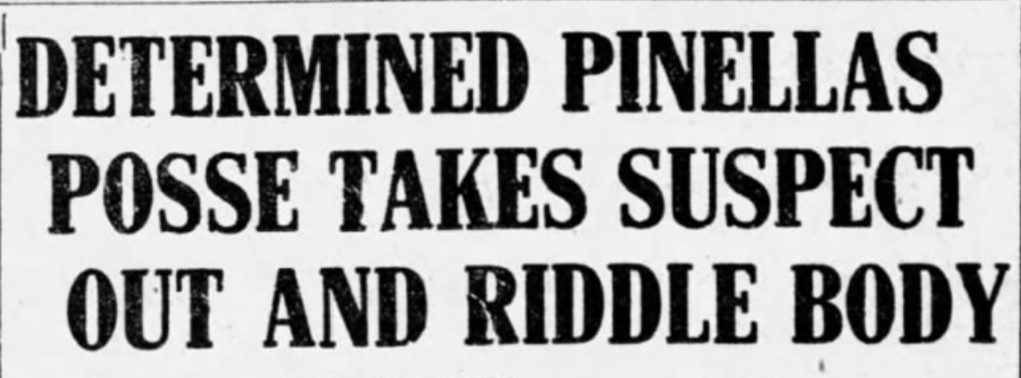

Front of marker memorializing John Evans.

/

Jacqueline Hubbard, co-chair of Pinellas Remembers.

/

Kanika Tomalin, Deputy Mayor for the city of St. Petersburg, Florida.

/

Brian Auld, President of the Tampa Bay Rays.

/

The marker memorializing John Evans is unveiled.

Lynching in America

In Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. Thousands more Black people have been killed by white mob lynchings whose deaths may never be discovered. The lynching of African Americans was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Though terror lynching generally took place in communities with functioning criminal justice systems, lynching victims were denied due process, often based on mere accusations, and pulled from jails or delivered to mobs by law enforcement officers legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented.

The Pinellas County marker is among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI. Visit this page for a list of markers in other communities.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.