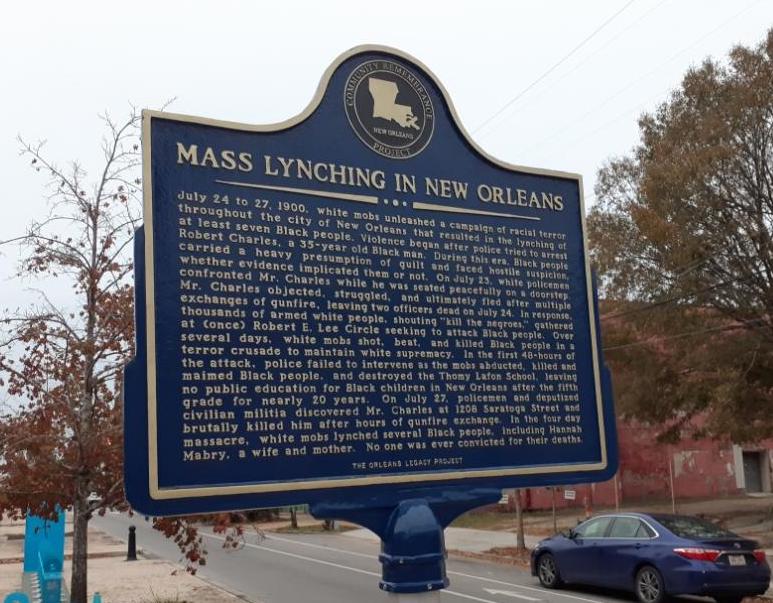

The Orleans Legacy Project partnered with EJI to hold a soil collection community ceremony and install a historical marker last month in remembrance of the July 1900 Mass Lynching in New Orleans, in which countless Black residents were terrorized, maimed, and killed by white mobs over several days. At least seven Black people are documented to have been killed in the mass lynching, including Mrs. Hannah Mabry.

The virtual ceremony celebrated the unveiling of the historical marker at Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in the Central City district of downtown New Orleans and documented the collection of soil, as descendants of Mrs. Hannah Mabry poured soil into jars to memorialize their loved one.

The Kumbuka African Drum and Dance Collective offered song and dance, and in true New Orleans fashion, a virtual second line with Wynton Marsalis and Friends closed out the ceremony. The coalition initially planned to hold a soil collection community ceremony in March, but the ceremony had to be canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Speakers at the virtual ceremony included State Rep. Royce Duplessis, New Orleans Mayor Latoya Cantrell, the Rev. Dr. Torin Sanders of Sixth Baptist Church, co-founder of the Ashé Cultural Arts Center Carol Bebelle, and Councilmember Jay Banks, who presented a Proclamation from the City Council that apologizes for the Mass Lynching of 1900.

Mr. Duplessis acknowledged that, as a member of the Louisiana legislature, he knows that the legacy of America’s history of racial terror and injustice “in many ways still plays out in policies that continue to be adopted and a culture that is perpetuated not only in our criminal legal system but through the injustices that we see in our education system, environmental justice policies, and healthcare system.”

In the past, few public memorials have addressed the nation’s history of lynching, and most victims have never been publicly acknowledged. “It could happen again today,” Queta Beasley Harris, great great great great granddaughter of Mrs. Hannah Mabry, said. “It does happen today. It’s the same thing over and over.”

Referring to the importance of the ceremony and soil collection for Mrs. Hannah Mabry, 11-year-old History Ecclesiastes said, “We’re helping out a soul.”

July 1900 Mass Lynching in New Orleans

From July 24 to 27, 1900, white mobs unleashed a campaign of racial terror throughout the city of New Orleans that resulted in the lynching of at least seven Black people.

On July 23, the violence began after police tried to arrest Robert Charles, a 35-year old Black man who was seated peacefully on a doorstep. Mr. Charles objected to the arrest, struggled, and ultimately fled after multiple exchanges of gunfire that left two officers dead.

Over the next several days, the entire Black community was targeted by thousands of armed white people who shot, beat, and killed Black people across the city. Police failed to intervene for two full days while mobs abducted, maimed, and killed Black people.

Mrs. Hanna Mabry, an elderly Black woman, was shot and killed by a mob of at least 20 white men on the night of July 26. In the weeks following her death, Mrs. Mabry’s son and daughter-in-law, Harry and Nancy Mabry, identified two white men in court as the mob leaders responsible for her death. The case against the two white men collapsed when death threats forced Mr. Mabry to recant his testimony. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to eight months in the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

On July 27, policemen and deputized civilian militiamen discovered Robert Charles in a building at 1208 Saratoga Street. The militia set the building on fire, and when Mr. Charles ran out, they killed him.

In the aftermath of the massacre, white mobs continued their plunder, looting businesses and destroying Black-owned property, including the Thomy Lafon School. As a result, there was no public school for Black children in New Orleans beyond the fifth grade until 1917.

Though the mob numbered in the thousands, no one was ever convicted for the deaths or injuries of countless Black residents, for the lost and destroyed property, or for the terror inflicted on the entire community.

Between 1877 and 1950, at least 15 Black people were lynched in Orleans Parish, Louisiana. Of this estimate, at least seven are documented to have been killed in the New Orleans Massacre of 1900: Robert Charles, Hanna Mabry, August Thomas, Louis Taylor, James Nelson, Joseph Scott, and a Black man whose name was not recorded.

The Orleans Legacy Project

In August 2018, members of the Orleans Legacy Project gathered to begin building their grassroots coalition after several members visited EJI’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Bringing together community activists, faith leaders, and local organizations—including “Take ‘Em Down NOLA,” the People’s Assembly, the Ashé Cultural Center, the St. Charles Center for Faith + Action, Undoing Racism workshop organizers, and representatives of Xavier and Tulane Universities—the coalition has engaged in an ongoing process of restorative truth-telling through facilitated community conversations about New Orleans’s history of racial violence and injustice.

Drawing on the city’s rich traditions of music, dance, and culture, the coalition has creatively deepened community conversations through theatrical plays and art projects that draw connections between the past and present. Following the historical marker and soil collection ceremony, the Orleans Legacy Project will host a Racial Justice Essay Contest for local public high school students in collaboration with EJI. Winners of the contest will be awarded a total of $5,000 in scholarships.

This is the first EJI historical marker installed in New Orleans Parish and the coalition intends to install additional markers for the other eight victims of racial terror lynching in the future.

Lynching in America

In Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. Thousands more Black people have been killed by white mob lynchings whose deaths may never be discovered. The lynching of African Americans was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many Black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known.

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented.

The New Orleans Parish marker is the first historical marker sponsored by EJI in Louisiana.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.