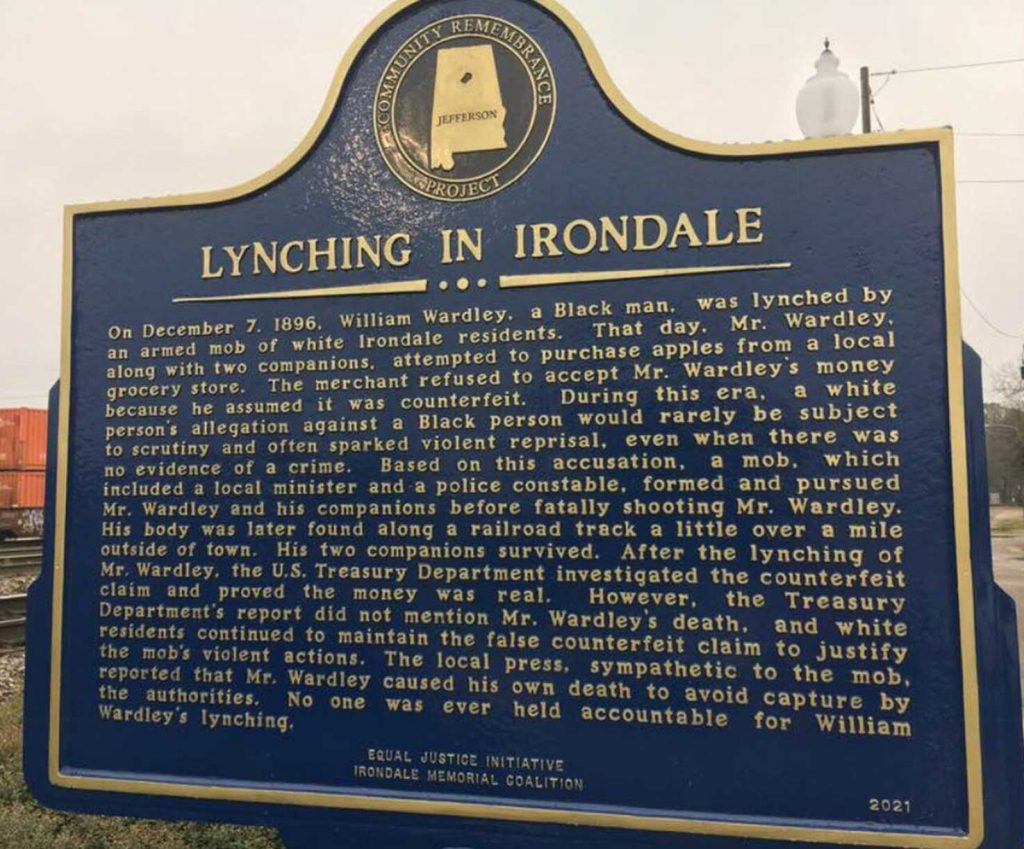

The Irondale Memorial Coalition partnered with EJI and the Jefferson County Memorial Project to unveil a historical marker for William Wardley, a Black man lynched in Irondale, Alabama, on December 7, 1896. The marker is located near 1900 First Avenue North, by the railroad tracks where Mr. Wardley’s body was found.

The historical marker was unveiled at a dedication ceremony on Tuesday, February 23. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, a small group of Irondale and Jefferson County residents attended in person and other community members joined via online streaming and social media.

Lynching in Irondale

On December 7, 1896, William Wardley, a Black man, was lynched by an armed mob of white Irondale residents. That day, Mr. Wardley, along with two companions, attempted to purchase apples from a local grocery store. The merchant refused to accept Mr. Wardley’s money because he assumed it was counterfeit.

During this era, a white person’s allegation against a Black person would rarely be subject to scrutiny and often sparked violent reprisal, even when there was no evidence of a crime.

Based on this accusation, a mob that included a local minister and a police constable pursued Mr. Wardley and his companions before fatally shooting Mr. Wardley. His body was later found along a railroad track a little over a mile outside of town. His two companions survived.

After the lynching of Mr. Wardley, the U.S. Treasury Department investigated the counterfeit claim and proved the money was real. However, the Treasury Department’s report did not mention Mr. Wardley’s death, and white residents continued to maintain the false counterfeit claim to justify the mob’s violent actions. The local press, sympathetic to the mob, reported that Mr. Wardley caused his own death to avoid capture by the authorities. No one was ever held accountable for William Wardley’s lynching.

Irondale Memorial Coalition

In response to the community outreach of the Jefferson County Memorial Project (JCMP), community members in Irondale began meeting to discuss how to document and memorialize the history of the racial terror violence in their community. Alex Melonas, an educator at the Altamont School, and Pastor Michael McClure of Revelation Church Ministries served as the co-chairs of the effort. They wanted to create a platform for the Irondale community to explore the historical context of racial injustice and the ways that legacy manifests today. The coalition includes local churches, schools, elected officials, and community leaders.

As part of the JCMP Fellows program, a local student, Margaret Weinberg, conducted additional research about William Wardley and served on the coalition. Her research coupled with the work of other students was published by JCMP to provide more information about the more than 30 victims of racial terror lynching documented in Jefferson County.

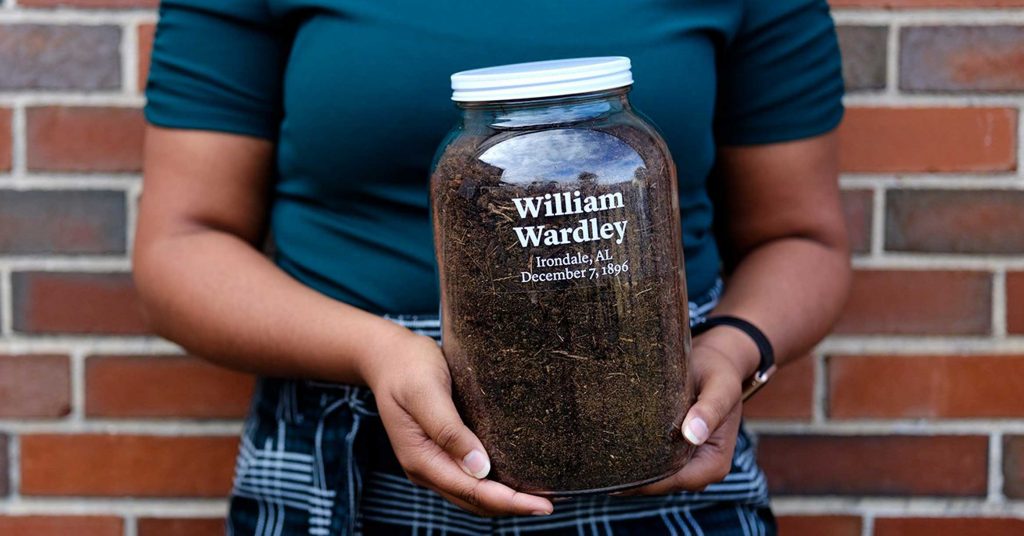

In November 2019, the coalition hosted a community soil collection ceremony in remembrance of Mr. Wardley at Revelation Church Ministries. Following the ceremony, the coalition and University of Alabama at Birmingham faculty and students partnered with the Irondale public library to host public education events, including a memory box exhibit in honor of Mr. Wardley.

/

Irondale and Jefferson County residents collected soil in memory of William Wardley, a Black man who was lynched in Irondale, Alabama, on December 7, 1896.

UAB Bloom Studio

/

The coalition hosted a community soil collection ceremony in remembrance of Mr. Wardley at Revelation Church Ministries in November 2019.

UAB Bloom Studio

/

Irondale and Jefferson County residents holding A History of Racial Injustice calendars at the soil collection ceremony.

UAB Bloom Studio

/

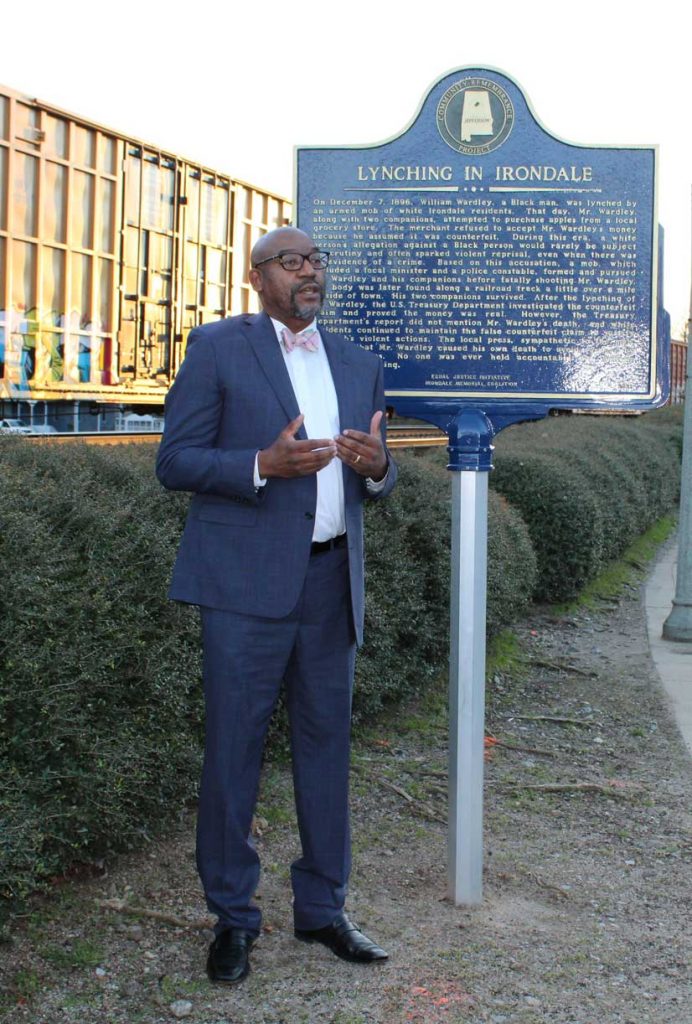

Irondale and Jefferson County residents attend the marker unveiling ceremony on February 23, 2021.

Irondale Memorial Coalition

/

Irondale Mayor James D. Stewart Jr. speaks at the marker dedication ceremony.

Irondale Memorial Coalition

/

The marker honoring Mr. Wardley memorializes the history of lynching in Irondale.

Greg Garrison/AL.comLynching in America

In Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. Thousands more Black people have been killed by white mob lynchings whose deaths may never be discovered. The lynching of African Americans was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

After emancipation, white Southerners remained committed to an ideology of white supremacy and used fatal violence and terror against Black communities to perpetuate the racial hierarchy and exploitative practices established during slavery. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and was generally tolerated in communities with functioning criminal justice systems. White mobs targeted Black women, men, and children who exercised their civil rights, defied racial social customs, or were accused of crimes.

Denied due process and equal protection under the law, often based on mere accusations, lynching victims were regularly pulled from jails or delivered to mobs by law enforcement officers required to protect them. Race, rather than the alleged offense, most often contributed to the fates of lynching victims like William Wardley. Of the more than 360 documented racial terror lynchings that took place in Alabama, at least 30 have been documented in Jefferson County.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of its effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented.

The narrative historical marker in Irondale is among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.