In the spring of 1846, Dred Scott and his wife Harriet Robinson Scott thought they had a chance at freedom. They lived in Missouri, a “slave state,” but their enslavers had previously taken them to free states or territories where slavery was outlawed. Other enslaved people had won so-called “freedom suits” in St. Louis courts thanks to Missouri’s “once free, always free” doctrine, which held that once an enslaved person had been taken to free territory, they remained free even after they returned to a “slave state.”

Mr. Scott suffered from tuberculosis and, at close to 50, he was considered old, especially for an enslaved person. Harriet Scott was in her late 20s. The couple had two small children, Eliza and Lizzie. Two sons had died in infancy.

Black families were at the mercy of enslavers who routinely sold and separated family members. Mr. Scott’s first wife had been sold away and sent to a plantation in Arkansas.

The man who enslaved Dred and Harriet Scott and their two children died in 1843, leaving his estate to his widow. Enslavers’ deaths sometimes resulted in children being sold away from Black families at estate sales. Mr. Scott tried to buy his family’s freedom, but the widow turned him down.

After that, the Scotts filed a freedom suit in St. Louis Circuit Court. “This is a case of a family that wants to stay together,” said historian and legal scholar Lea VanderVelde. The Scotts cited the case of a woman identified as Rachel who, like them, had been taken by her enslaver to Fort Snelling, in a free territory where slavery was illegal, before returning to Missouri. She later won her freedom suit.

Enslavers often retaliated against people who filed lawsuits, but researchers have unearthed records of nearly 300 freedom suits—including the Scotts’—filed in St. Louis between 1814 and 1860. More than 100 plaintiffs succeeded in winning their freedom.

Those who risked violent reprisals and separation from their loved ones to sue for their freedom should be celebrated as “America’s first civil rights litigants,” historian David Thomas Konig said.

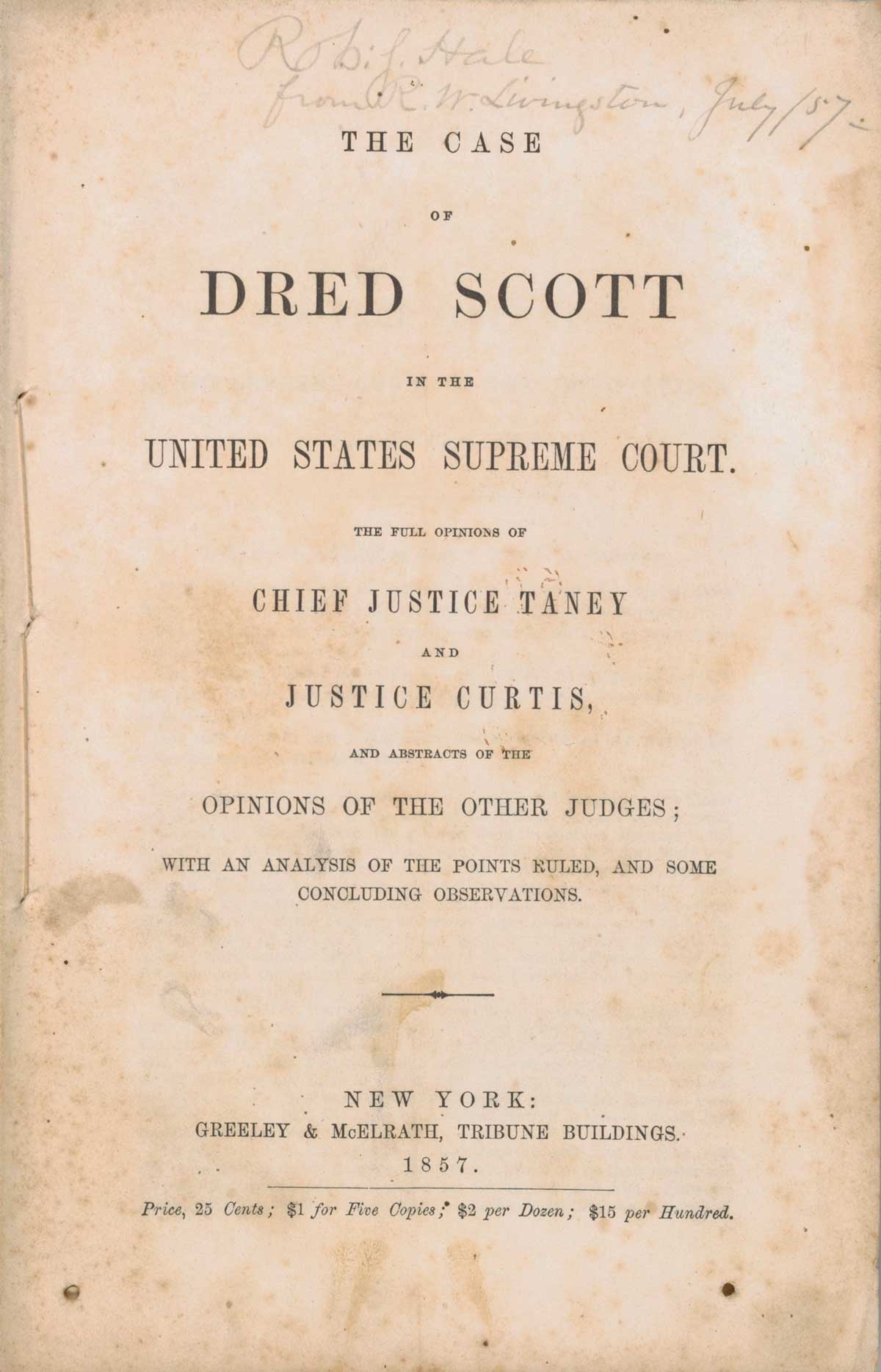

The Decision

The Scotts’ case moved slowly through the legal system, reaching the U.S. Supreme Court in 1856. Most of the justices were from families that enslaved people. Chief Justice Roger Taney, the son of wealthy Maryland tobacco planters, had emancipated the enslaved people he had inherited, but he remained, at 80, a staunch defender of white supremacy—as was Andrew Jackson, the president who had put him on the court. By one account, Justice Samuel Nelson’s tuition at Middlebury College was financed in part by his father selling an enslaved girl.

On the morning of March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Taney read aloud the 7-2 majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford. The Scotts were not, and never could be, American citizens, the Court held, and therefore had no right to sue in federal court. They would remain enslaved.

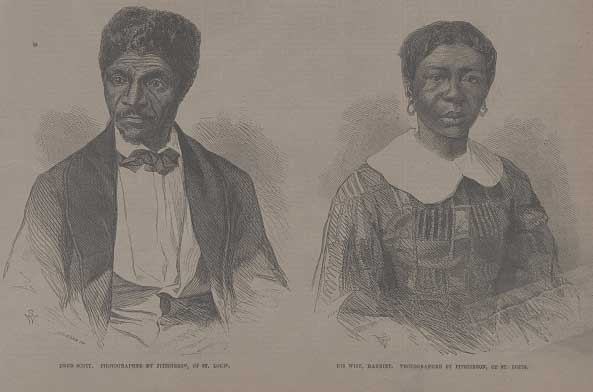

An illustration of Dred and Harriet Scott. (Library of Congress)

The Court’s decision denied citizenship to all Black people in America—to the four million enslaved men, women, and children whose backbreaking, unpaid labor powered the nation’s economy, as well as to the several hundred thousand Black people who were free.

The Court’s ruling validated the doctrine of racial difference and hierarchy that had been used to justify racialized slavery and continues to haunt our nation today The Court described Black people “as beings of an inferior order” and concluded that Black people are “altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations.” The Court also found that Black people are “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”.

The Court viewed the principle in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” through the lens of white supremacy. Those words “would seem to embrace the whole human family,” the Court acknowledged. However, “it is too clear for dispute,” that no one had ever intended such equality to apply to Black people, enslaved or free. By the “common consent” of all “civilized Governments and the family of nations,” the Court said, “the negro race” had been ”doomed to slavery.”

The Court could have limited its judgment to the Scotts’ quest for citizenship. Instead, the Court broadened the ruling to address the bitterly contested question of slavery in the territories.

In 1820, Congress had enacted the Missouri Compromise, which banned slavery in territories north of the Missouri state line. Mr. Scott’s case was based largely on his enslaver having taken him to Fort Snelling, which was located in free territory that is now Minnesota. But the Court held that Mr. Scott was property and the Constitution does not allow the government to deprive a citizen of property without due process of law. With this reasoning, the Court ruled against Mr. Scott and legalized slavery in the territories by overturning the Missouri Compromise. It was only the second time the Court had overturned an act of Congress.

Amid escalating national tensions over slavery, Dred Scott’s obscure “freedom suit” took on monumental significance.

Newly elected President James Buchanan had pressured Associate Justice and fellow Pennsylvanian Robert Grier to persuade other members of the Court to broaden the ruling in favor of expanding slavery. In his inaugural address on March 4, 1857, Mr. Buchanan—knowing how the court was about to rule—predicted that the decision would settle the slavery question and that the country would be “most happy” with the ruling.

Justice Benjamin Curtis, from Massachusetts, wrote a stinging dissent and resigned from the Court shortly afterward, reportedly in part because of the decision.

Abraham Lincoln, then a candidate for U.S. Senate from Illinois, said the Court had turned the Declaration of Independence into a “mangled ruin.”

“The court had lost all moral authority,” historian Eric Foner said, “at least in the northern half of the country.”

“In the spring of 1857,” said historian David Blight, “to be Black in America was to live in the land of the Dred Scott decision, which in effect said, ‘You have no future in America.’”

Black Americans Respond

Black leaders who were already risking their lives to resist slavery and advocate for equality voiced their outrage at the Court in editorials and speeches. A month after the decision, hundreds of Black people gathered at the Israel Church in Philadelphia, four blocks from Independence Hall, to draft protest resolutions. Charles Remond declared that his grandfather had fought for his country in the Revolutionary War. Now, that same country “grinds us under its iron hoof and treats us like dogs,” he said.

Reporting on the Philadelphia meeting in The Provincial Freeman, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, a Black abolitionist who had moved to Canada, implored Mr. Remond and other leaders: “Your national ship is rotten, sinking. Why not…leave that slavery-cursed republic?”

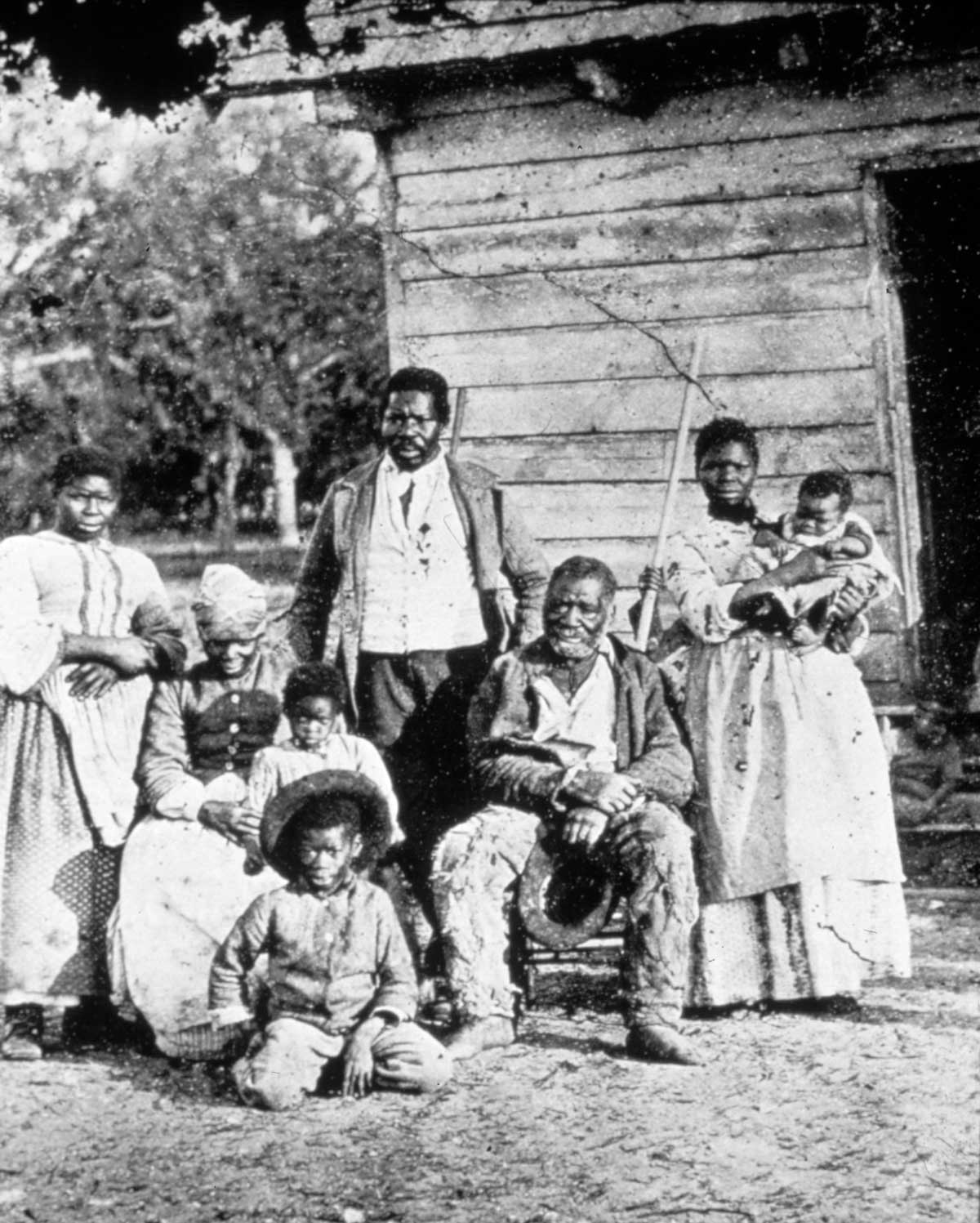

Five generations of an enslaved family in South Carolina, 1862. (Library of Congress)

Robert Purvis, a Black leader who was active in the Underground Railroad, said that Dred Scott meant the government had “deliberately, before the world [declared] one part of its people disenfranchised and outlawed.”

Frederick Douglass declared that “this infamous decision of the Slaveholding wing of the Supreme Court maintains that…slaves are property in the same sense that horses, sheep, and swine are property.”

The Court’s thundering denial of the humanity of Black people drove Mr. Douglass into a depression, historian David Blight wrote, and yet he kept giving electrifying speeches about the promised future of Black people as free and equal Americans. The justices did not have the last word, Mr. Douglass declared, God did. The Court had made America “awake” to the slavery question at last, he said. “My hopes were never brighter than now.”

Mr. Douglass’s former North Star co-editor, Martin Delany, who had been admitted to Harvard Medical School but was forced out after white students complained, responded to Dred Scott—and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850—by writing a novel whose hero escapes bondage and plots an overthrow of slavery. The novel was serially published in The Anglo-African Magazine in 1859.

Before Dred Scott

The role of the Supreme Court in legitimizing slavery and embedding the narrative of racial hierarchy in the legal system long predated Dred Scott and continued long afterward.

In 1842, Margaret Morgan and her six children were seized from their beds in Philadelphia in the middle of the night by Maryland lawyer Edward Prigg and three other white men, loaded into an open wagon, and taken forcibly south to Maryland, where slavery was legal.

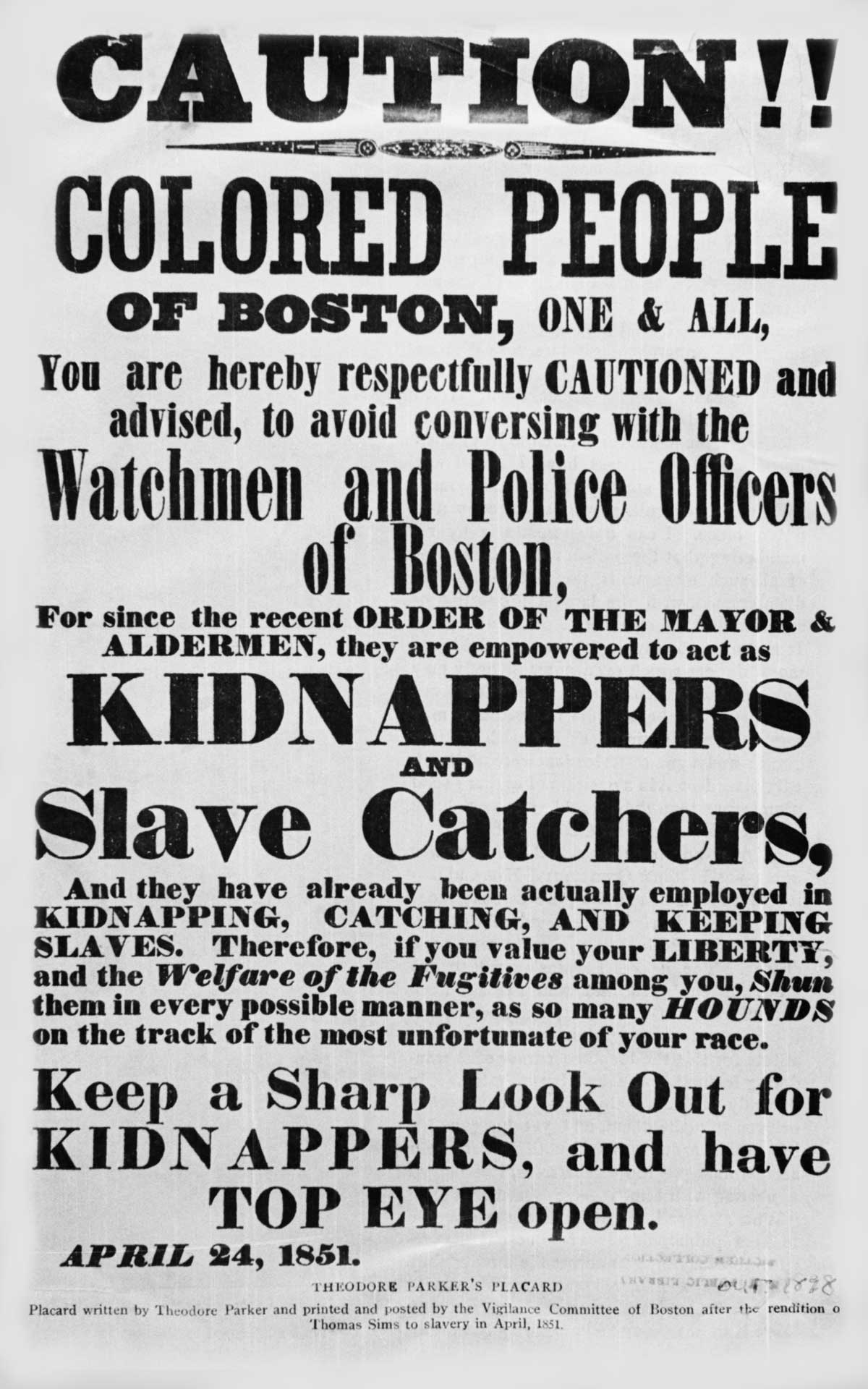

An 1851 placard posted in Boston warns Black residents about local police officers kidnapping and re-enslaving people under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. (Corbis)

Mrs. Morgan had been born in Maryland, where her mother had been enslaved. But the will of her mother’s long-deceased enslaver seemed to free Margaret Morgan. She married a free Black man from Pennsylvania, and in 1832 they moved to Philadelphia. They did not consider themselves fugitives. But the descendants of the man who enslaved Mrs. Morgan’s mother hired Mr. Prigg to “return” Mrs. Morgan and her children to Maryland.

Mr. Prigg and the other men who kidnapped and trafficked Mrs. Morgan and her children to Maryland were convicted of violating a Pennsylvania law that barred profiteering kidnappers from capturing Black people and turning them over to enslavers or auctioneers. But in an 8-1 vote, the Supreme Court struck down that law as unconstitutional. The Court’s opinion pointed to the Constitution’s section enabling enslavers to “retrieve” fugitives from bondage.

In a separate opinion in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, Chief Justice Taney said anyone who prevented enslavers from forcing people back into bondage was “a wrongdoer,” and any state law that interfered was “null and void.”

Prigg was one of several cases in the 1840s and ‘50s where the Taney Court upheld so-called fugitive slave laws designed to aid enslavers. As Andrew Jackson’s attorney general, Mr. Taney had written in 1832 that Black Americans were “a degraded class” and any rights they enjoyed were because of white Americans’ “benevolence.”

Margaret Morgan and her children disappeared into bondage. Mr. Prigg, who went unpunished along with his accomplices, became a sheriff.

The Reconstruction Amendments

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, enacted between 1865 and 1869, effectively reversed Dred Scott by abolishing slavery (except as punishment for crimes), extending citizenship rights to Black Americans (including the right to vote for Black men), and guaranteeing them equal protection of law.

But even as Dred Scott was overturned, white supremacy was not. White people organized a brutal resistance against Black citizenship, deploying violence and terror to crush Reconstruction.

In response, Congress passed a series of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871, the broadest being the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. Southern white leaders called that act an unjustified federal intrusion on state authority.

Adopting the Southern view, the Supreme Court issued opinions that severely undermined the legal architecture of Reconstruction. In case after case, the Court failed to protect Black people from terror, violence, and lynchings. While Black men who tried to vote risked being maimed and murdered, the Court concerned itself with whether laws like the Enforcement Acts might “fetter and degrade the State governments.”

The Court’s dismantling of Reconstruction was orchestrated by John Archibald Campbell, a white attorney and former Supreme Court Justice who had voted with the majority in Dred Scott. Mr. Campbell, an enslaver, had left the bench in April, 1861 to help lead the Confederate States of America. After the Confederacy lost the Civil War, he bitterly opposed Reconstruction.

In 1872, Mr. Campbell represented a group of white New Orleans butchers who claimed that efforts by Louisiana’s Reconstruction legislature to regulate their industry violated their Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. They lost their appeal to the Supreme Court in the 1873 Slaughter-House Cases, but the ruling gave Mr. Campbell and other opponents of Reconstruction what they wanted. The Court severely undercut the Fourteenth Amendment by holding that citizenship rights were enforceable only in state courts, which were dominated by the white ruling class and utterly hostile to claims by Black people in the South.

A Massacre Unpunished

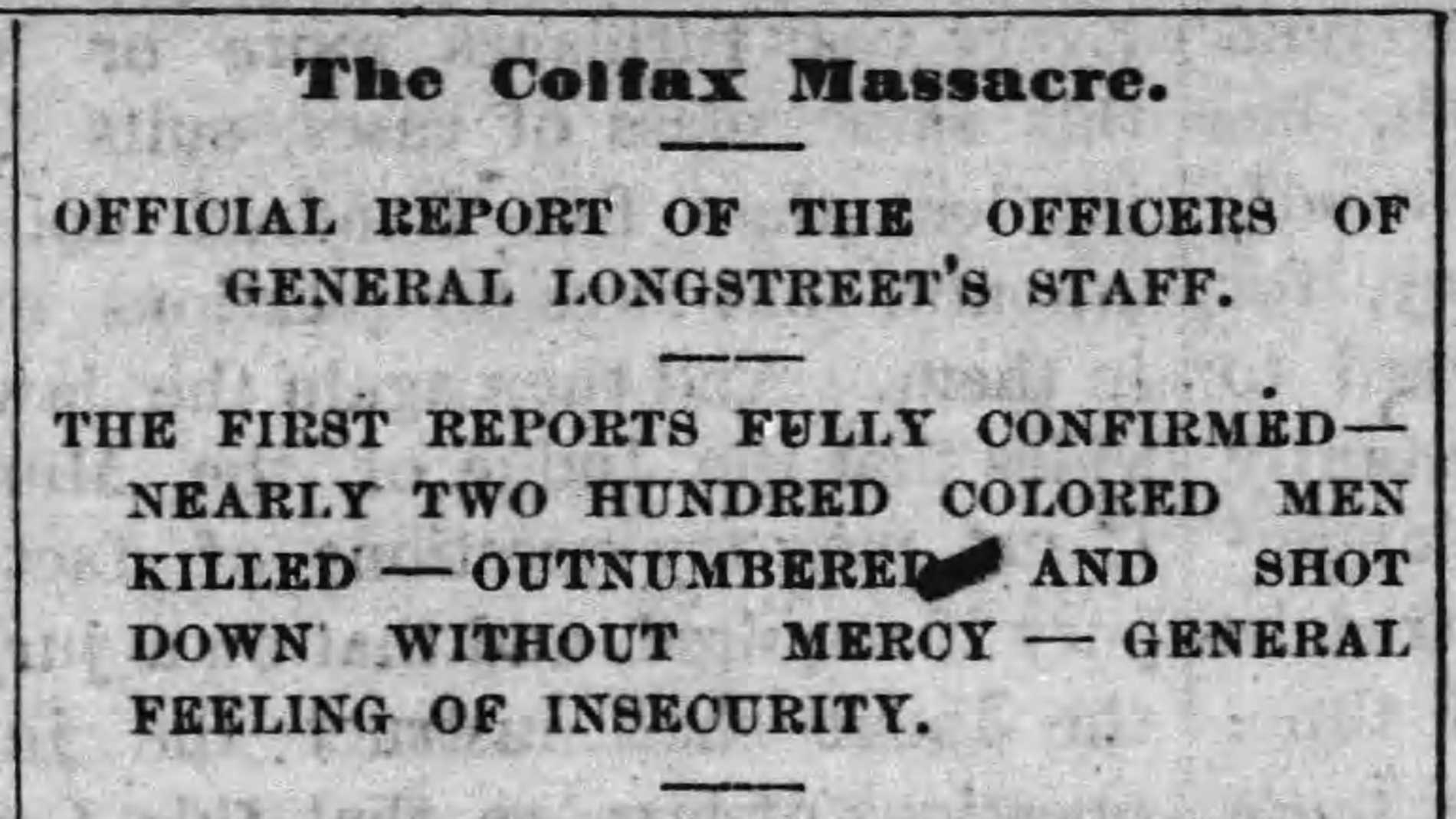

Nearly three years later, in another case that went before the Supreme Court, John Campbell represented white men who had participated in the 1873 massacre of an estimated 150 Black people in Colfax, Louisiana. The bloodbath followed Louisiana’s fiercely contested 1872 gubernatorial election, where supporters of the white supremacist candidate refused to accept his defeat and set out to install their own local officials in Grant Parish. Black citizens surrounded the Grant Parish courthouse and other municipal buildings in Colfax to prevent the takeover. Hundreds of armed white men attacked the courthouse and killed an estimated 150 Black people, many of whom had already surrendered. Three white men died.

Rutland Weekly Herald (Rutland, Vt.), May 1, 1873

Under the 1871 Enforcement Act, federal prosecutors secured convictions of William J. Cruikshank, a cotton planter who had served on the parish governing board, and two other white men. They appealed, and the Supreme Court reversed the convictions, ruling in Cruikshank vs. United States that the Fourteenth Amendment “prohibits a state,” not individuals, from violating people’s rights. Mr. Cruikshank and other perpetrators of one of the bloodiest acts of racial terror during Reconstruction went unpunished.

Legal scholar Leonard Levy wrote that Cruikshank “in effect, shaped the Constitution to the advantage of the Ku Klux Klan.”

The decision eviscerated the Enforcement Acts. The Justice Department dropped 179 Enforcement Act prosecutions in Mississippi alone. Emboldened white men no longer wore masks and increasingly carried out daylight attacks on African Americans.

Fleeting Freedom for Dred Scott

Soon after Dred Scott, descendants of the Scotts’ enslavers “purchased” the Scott family and freed them. Mr. Scott found work as a porter at a St. Louis hotel. He told a local reporter—in some of the few published words ever attributed to him—that the long court fight had given him “a heap [of] trouble,” according to The Anti-Slavery Bugle. If he had known it would take so long, Mr. Scott said, he would not have sued. He wished he could travel the country to “tell who he is.”

But he died of tuberculosis in 1858, before he turned 60. Born enslaved, Mr. Scott lived for only 16 months as a free man.

Harriet Scott, who worked as a laundress into her later years, died in 1876. She was 61.

Descendants gather at Dred Scott’s grave at the Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri, in 2007. (MSNBC)

Roger Taney died in 1864. In 1865, Congress tried and failed to fund a bust of him to be placed in the Capitol along with those of his predecessors. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts argued that a man who had done evil “should not be complimented in marble.”

A few years later, as white attitudes about Reconstruction began to shift, Congress approved the bust of the late chief justice and it was installed in the Capitol.

In 2022, after George Floyd’s murder and amid a movement to remove Confederate monuments along with memorials to those who upheld white supremacy, Congress voted to replace Mr. Taney’s bust with one of Thurgood Marshall, the great civil rights lawyer who in 1967 became the Supreme Court’s first Black justice. In February, 2023, the bust of Mr. Taney was removed from the Capitol.

In September, 2023, through the efforts of Mr. Scott’s great-great-granddaughter, Lynne M. Jackson, a towering memorial was erected at his grave in St. Louis.

Roger Taney’s descendant, Charles Taney III, publicly apologized to Ms. Jackson, and to all African Americans, “for the terrible injustice of the Dred Scott decision” on its 160th anniversary. Ms. Jackson hugged him.

While individual justices, too, have condemned the decision, the Supreme Court has never officially apologized for Dred Scott.