Community members, activists from Showing Up for Racial Justice and the Fenix Youth Project, and EJI staff joined together for a pilgrimage along Maryland’s Eastern Shore, collecting soil at the sites where six young men were lynched, as part of EJI’s Community Remembrance Project.

The journey began on October 20 at the site in Somerset County where George Armwood was lynched on October 18, 1933. Mr. Armwood’s descendants, including Tina Johnson, collected soil in a solemn ceremony honoring their ancestor. “You can’t get justice for slavery, but we can give him justice by remembering that this awful thing happened,” Ms. Johnson said. “With this vigil, with this remembrance, we’re giving justice to my ancestor.”

Then, on October 27, a group including students from Salisbury University, local faith leaders and historians, and community organizers gathered in front of the Wicomico County Courthouse in Salisbury, where Garfield King was lynched in a brutal public spectacle lynching on the courthouse lawn in 1898.

Garfield King, an 18-year-old Black man, was accused of shooting a white man during an era when allegations against Black people were rarely subject to scrutiny and often sparked violent reprisals. The deep racial hostility that permeated American society burdened Black people with a presumption of guilt. Mr. King maintained that he was innocent and had shot the man in self-defense, but he was never afforded the dignity of a trial.

Instead, on May 26, 1898, a mob of more than 100 white people broke into the Wicomico County Jail, forced open the cell where Mr. King was awaiting trial, and dragged him out. They tied a clothesline around his neck and hanged him from a tree on the courthouse lawn. The line snapped, and Mr. King dropped to the ground, was jolted out of unconsciousness, and tried to escape. The mob pursued and recaptured him, beat and shot him, and then hanged him a second time, firing dozens of rounds into his dangling body. Some participants reportedly took home bloody pieces of rope as souvenirs.

Mr. King’s mangled body was placed in the old Salisbury engine house, where hundreds of residents came to see it the next day. As with many racial terror lynchings, the violent and public torture was intended not only to inflict brutality on Mr. King, but also to send a message of white dominance to the entire Black community. Mr. King’s lynching inflicted terrible trauma on his loved ones and on all of the Black people who saw his corpse or heard the violent details of his death.

A grand jury heard testimony from more than 50 witnesses to Mr. King’s lynching, each of whom testified he was unable to identify any participant in the lynch mob. The jury concluded that Mr. King was killed by “persons unknown,” and no one was held accountable for his death.

This past Saturday, a volunteer read a description of the lynching of Mr. Garfield before the group collected soil in his honor at a tree outside the Wicomico County Courthouse on East Main Street. A Salisbury University student observed that “in unearthing this soil, we are unearthing history that must never be forgotten.” The group then placed new soil at the collection to symbolize healing, explaining that the new soil signifies an opportunity for new growth and renewed hope.

/

/

/

/

/

/

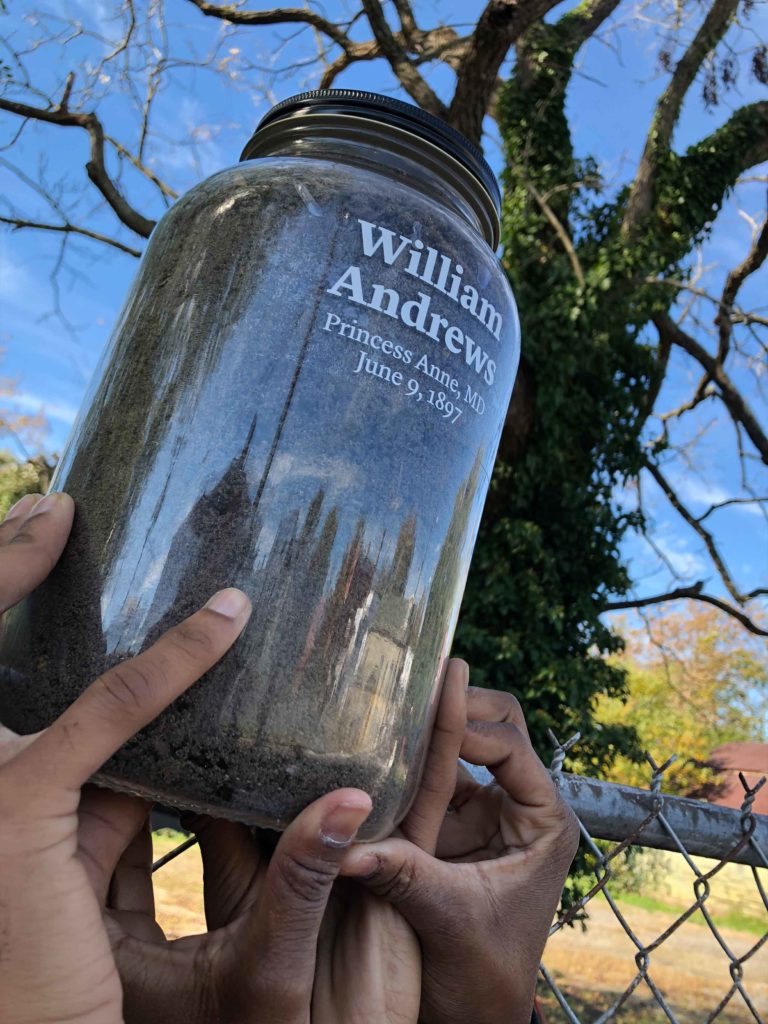

The group then traveled to Princess Anne to collect soil in honor of Isaac Kemp and William Andrews.

In the early morning of June 8, 1894, a white mob broke into the Somerset County Jail in Princess Anne and lynched Isaac Kemp, a 23-year old Black man, as he lay chained to the floor of his cell.

Edward Carver, a white deputy sheriff, had been killed during an altercation at a liquor store, and Mr. Kemp was arrested along with 11 other Black men and accused of involvement in the deputy’s death. Mr. Kemp was accused of being the ringleader of the group and was placed in a separate cell from the other prisoners.

Many African Americans were lynched across the United States under accusation of murder. During this era of racial terror, mere suggestions of Black-on-white violence could provoke mob violence and lynching before the judicial system could or would act. The deep racial hostility permeating American society often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was discovered, whether or not there was evidence to support the suspicion, and accusations lodged against Black people were rarely subject to serious scrutiny.

Once inside the jail, the lynch mob found Mr. Kemp’s cell and shot him three times through the grating of his door. Unsatisfied, the mob searched the jail and found the keys to his cell, opened the door, and “with a hurrah,” fired more than 50 rounds into Mr. Kemp’s body. Chained to the floor of his cell, Mr. Kemp had no chance to flee or defend himself. The lynch mob left Mr. Kemp’s brutalized body in the cell, bid the jailor “good night,” and walked away.

On June 9, 1897, a mob of more than 1000 white people lynched 17-year-old William Andrews near the Somerset County Courthouse. A white woman had accused the teenager of assaulting her on her way home, and he was arrested and taken to Baltimore City amid threats of lynching. William maintained his innocence and explained that the woman had passed him earlier that day while he was picking strawberries and that they had walked by each other a second time that afternoon, but did not speak to each other.

Almost 25 percent of documented lynchings were sparked by charges of sexual assault, at a time when the mere accusation of sexual impropriety regularly aroused violent mobs and ended in lynching. During this era, Black men were taught from an early age to be wary around white people, especially white women, because even the most innocent or accidental interactions, such as bumping into, startling, or being alone with a white woman could spark serious allegations and deadly violence.

The court quickly set a trial date, but as soon as William was returned to Princess Anne, hundreds of white men gathered at the courthouse, calling for William’s blood. After the sheriff falsely claimed that William confessed, and as the lynch mob grew, an all-white jury indicted William in 20 minutes and he pleaded guilty to assault. He was sentenced to death, and the crowd outside erupted in cheers. When police led William from the courthouse, the mob pushed past the judge, who was urging them to refrain from violence, and brutally attacked William.

During this era, it was not uncommon for lynch mobs to seize their victims from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or out of the hands of police. Though they were armed and charged with protecting the men and women in their custody, police almost never used force to resist white lynch mobs intent on killing Black people.

As William pleaded for mercy, the mob knocked him down, beat him in the head with clubs, stabbed his body with penknives and razors, and trampled him on the courthouse lawn. As he lost consciousness, William begged for death. The mob dragged his limp body to a big oak tree on Church Street, about 30 yards from the courthouse, hanged him from a branch with a rope around his neck, and shot at him until their ammunition was spent. The mob soon dispersed, but William’s mutilated body was left hanging until late afternoon.

The court summoned a jury of inquest, but law enforcement officers refused to identify any members of the mob and the jury ruled that William had died from blows inflicted by “persons unknown.”

After collecting soil from under an oak tree near the courthouse, the Community Remembrance group traveled to Crisfield, Maryland, to the site where 22-year-old James Reed was lynched on July 28, 1907, by a mob of hundreds of white people as he was being transported to jail on allegations of killing a white police officer.

When they heard reports that James Reed had allegedly shot and killed a white police officer, local authorities chartered a fleet of small gasoline launchers to pursue him by boat. According to newspaper reports, hundreds of white people congregated in the waterside community of Crisfield in anticipation of the lynching. On the morning of July 28, a search party spotted and apprehended Mr. Reed in a small boat about 10 miles from shore, and the crowd howled with excitement and rushed to the docks.

As Mr. Reed was brought onto shore, members of the mob brutally beat and kicked him to death, crushing his skull. They then dragged his broken body to a telegraph pole and hanged him for public display. According to local news reports, hundreds of white people came to see and photograph Mr. Reed’s body before it was taken down and hastily buried in a marsh later that evening.

During this era, crowds of hundreds or thousands of white people attended public spectacle lynchings, as participants or spectators, and often included elected officials and prominent citizens. White press coverage regularly defended the lynchings as justified, and cursory investigations rarely led to identifications of lynch mob members, much less prosecutions. White men, women, and children fought over bloodied ropes, clothing, and body parts, and proudly displayed these “souvenirs” with no fear of punishment, while buying photograph postcards to mail to distant loved ones without shame.

Unsatisfied even after Mr. Reed was dead, members of the mob returned later that night, dug up his corpse, and fired bullets into it before throwing it on a large bonfire. A crowd congregated around the fire to watch Mr. Reed reduced to ash and purchase souvenirs, including pieces of rope and photographs of the lynching. After burning Mr. Reed’s body, gangs of white people rode through the African American community, pulled Black people out of their homes, and beat them. Several African American men were threatened with death if they did not leave town immediately. In the following days, the city council met and resolved to shut down several Black businesses, and many Black residents were arrested for vagrancy. The practice of terrorizing members of the African American community at random in the wake of a racial dispute was common during this period, as lynchings were used more as a tool of racial oppression than criminal punishment.

The Baltimore Sun reported that the white people who participated in the lynching and subsequent attacks acted boldly and with complete impunity. James Reed was lynched in broad daylight by men who did not wear masks and faced no resistance from law enforcement officials. Like so many racial terror lynchings, James Reed’s horrific death was not the action of a few marginalized vigilantes or extremists; it was a public act that implicated the entire community. Racial terror lynching sent a clear message to African Americans that they were deemed less than human; that their subjugation was to be achieved through any means necessary; and that white lynch mobs need not fear legal repercussions.

The volunteers collected sandy soil in honor of Mr. Reed, and reflected on the legacy of white supremacy and racial violence today. They then returned full-circle to the Wicomico County Courthouse to collect soil for Matthew Williams, who was 23 years old when he was accused of shooting his white employer in Salisbury, Maryland. Mr. Williams had been shot in his leg and shoulder, and news that he had been admitted to Peninsula General Hospital angered many local white people, who gathered on the lawn chanting, “Let’s lynch him!” When the mob stormed the building on December 4, 1931, they faced little resistance. The hospital superintendent reportedly told them, “If you must take him, do it quietly.” The mob dragged Mr. Williams from his hospital bed, beat him and repeatedly stabbed him with an ice pick before hanging him from a tree in front of the Wicomico County Courthouse.

After the hanging, the mob cut down Mr. Williams’s body, dragged it a few blocks from the courthouse, doused it in gasoline, and set it aflame. Mr. Williams’s eyes were removed from their sockets and members of the mob reportedly took pieces of his body as souvenirs. The charred remains were tied to the back of a truck and dragged through Salisbury “so all the colored people could see him.”

Despite the terror this instilled in the entire Black community, Mr. Williams’s family came forward to claim the remains of their loving son. His aunt, Addie Black, told the Afro-American, “I wanted to leave the house for fear that the mob would attack me and my family, but my husband persuaded me not to leave until we made some arrangements for the body.” But after a deputy sheriff who arrived on the scene as Mr. Williams’s burned body was hanging from a lamp post on the corner of Lake and Main streets told the crowd, “We are going to take that body. You’ve had your fun now and you ought to be satisfied,” police dumped Mr. Williams’s corpse in the woods a few miles outside of town and covered it with leaves and burlap.

On March 18, 1932, after hearing from 124 witnesses, the grand jury concluded that it “did not have sufficient evidence to return an indictment” in Mr. Williams’s death.

As the group collected soil from beneath a tree on the courthouse lawn, they were struck by the white community’s decision to place a Confederate marker at the site of Mr. Williams’s brutal murder, observing that the way Black people feel walking by that marker today echoes the terror Black people experienced seeing Mr. Williams’s mangled body hanging for hours on the courthouse lawn in 1933.

In the days following the lynching of Matthew Williams, white mobs roamed the streets of Salisbury — dubbed Maryland’s “Lynch Town” — targeting any unprotected Black person they encountered. On the morning of December 6, 1931, a second victim of the white mob that killed Matthew Williams was found on the corner of College Avenue and Railroad Street. He was found dressed in blood-soaked overalls, a sweater, a brown khaki shirt, and worn Army shoes. He was about 35 years old and weighed about 160 pounds, and police found bacon and half a ham, wrapped in brown paper, near his body. Authorities concluded he had gone to the grocery store on the evening of December 5 and was attacked and murdered by the white mob on his way home. The attack left the man unrecognizable, fracturing his skull and crushing the entire left side of his face, and his name remains unknown.

During this era of racial terror, white mobs sought to maintain white supremacy and dominance by instilling fear in entire Black communities through brutal violence that was often unpredictable and arbitrary. It was common for a lynch mob’s focus to expand beyond a specific person accused of an offense and target family members, neighbors, or any and all Black people unfortunate enough to be in the mob’s path. Many African Americans were lynched not because they were accused of any crime, but simply because they were Black and present after the initial lynching was complete.

“It hurts knowing this was allowed to happen and has been happening for as long as America has been a country,” Steven Williams, a 21-year-old student at Salisbury University told the Delmarva Daily Times. “It’s definitely a very surreal feeling to be able to see these sites and affect them in a way we hope is positive.”

At each site, local organizers facilitated discussions about the lingering impact of the era of racial terrorism in America.

“The conversations that have happened, traveling to these sites has been so profound,” said Amber Green, Executive Director of the Fenix Youth Project. “To see the conversations and to see the different perspectives it’s a sign of healing, it’s also just a sign of bringing communities together. The main goal was to take our journey and our experience [and] share it with the community.”

Lynching in America

In 2007, Sherrilyn A. Ifill outlined the critical need for memorializing the history of lynching in this country. Her powerful book, On the Courthouse Lawn, detailed these Eastern Shore lynchings and persuasively made the case for why public memorials on lynching should be an American priority.

Thousands of Black people were the victims of lynching and racial violence in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The lynching of African Americans during this era was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching was most prevalent in the South. After the Civil War, violent resistance to equal rights for African Americans and an ideology of white supremacy led to violent abuse of racial minorities and decades of political, social, and economic exploitation.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many Black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known, but EJI has documented 29 African American victims of racial terror lynching killed in Maryland during this era.

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project

In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who labored under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.

– EJI Director Bryan Stevenson

EJI collects soil from lynching sites as part of its Community Remembrance Project, a campaign to recognize the victims of lynching that includes erecting markers at lynching sites and creating a national memorial that acknowledges the horrors of racial terror in America. EJI believes that by reckoning with the truth of the racial violence that has shaped our communities, community members can begin a necessary conversation that advances healing and reconciliation.

EJI joined a pilgrimage along Maryland’s Eastern Shore, collecting soil at the sites where six young men were lynched.