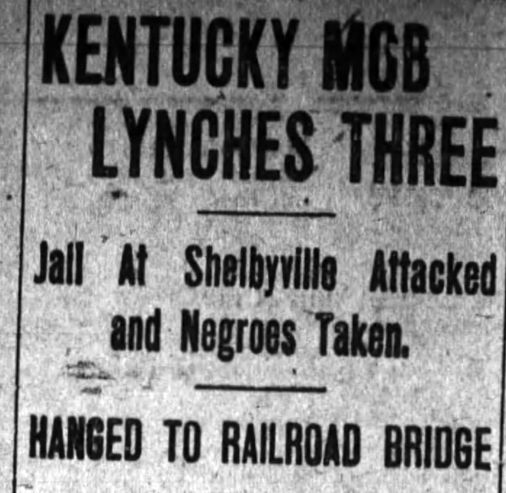

The Shelbyville Community Remembrance Project Coalition partnered with EJI to erect three historical markers that memorialize the lynchings of six people in Shelby County, Kentucky—Reuben Dennis, Sam Pulliam, Wade Patterson, Eugene Marshall, Clarence Garnett, and Jimbo Fields.

The coalition originally planned to install all three markers last fall, but those plans were postponed due to Covid-19.

On April 10, the Shelbyville Community Remembrance Project Coalition and a small number of guests unveiled three historical markers in front of the old Shelby County Jail and Courthouse in downtown Shelbyville. Several members of the coalition and state and local officials were invited to give remarks.

Shelby County Judge/Executive Dan Ison was instrumental in securing authorization to install the markers at the site of the former jail. He spoke about the recently restored 105-year-old courthouse and said that “we must teach history, we must display our history” in response to those who challenged the importance of the markers.

Sister Janice Harris, Chairperson of the SCRPC and President of the Shelbyville chapter of the NAACP, talked about the process of healing that the coalition experienced by facilitating the memorialization efforts. “We were all in this together. We could not bury our hands as many have done over the years. So we talked through the difficult discussions about race. Sometimes it was not so comfortable but we got through it,” she said. “We had some tears, we got emotional, and then we prayed.” She declared that the markers are the start of healing for the entire Shelbyville community.

Other speakers included Secretary to Kentucky Governor J. Michael Brown and Kentucky NAACP President Marcus Ray. Shelbyville Mayor David Eaton offered remarks in video format as he could not be present in person.

The coalition plans to facilitate a Racial Justice Essay Contest for local public high school students this fall.

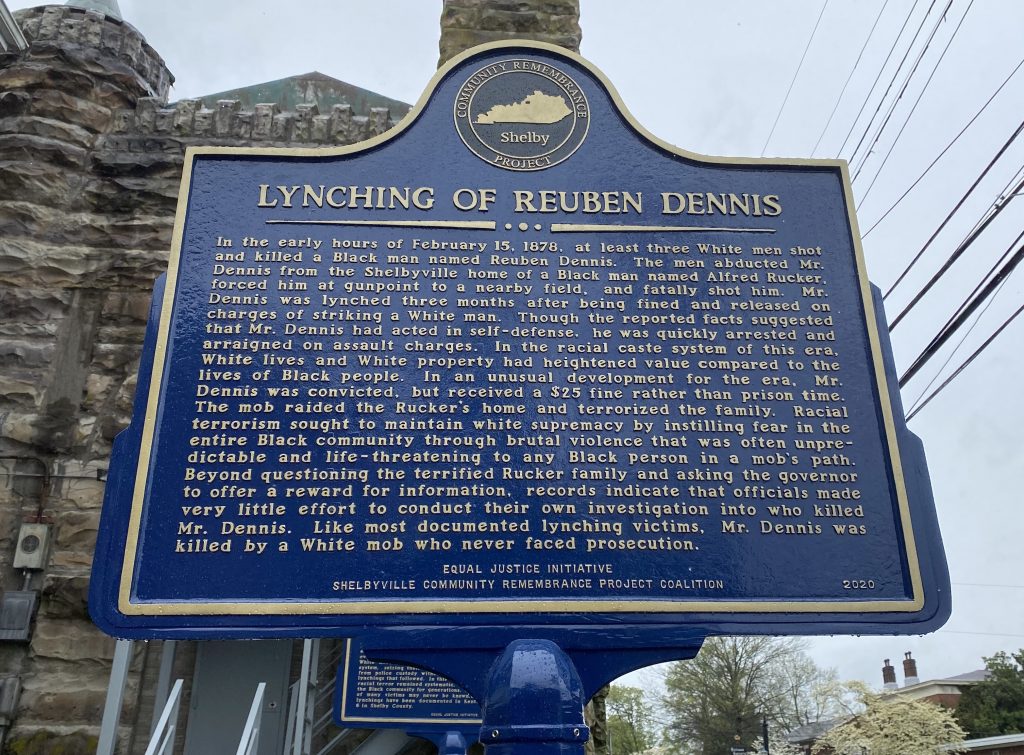

Lynching of Reuben Dennis

In the early hours of February 15, 1878, at least three white men shot and killed a Black man named Reuben Dennis. The men abducted Mr. Dennis from the Shelbyville home of a Black man named Alfred Rucker, forced him at gunpoint to a nearby field, and fatally shot him.

Mr. Dennis was lynched three months after being fined and released on charges of striking a white man. Though the reported facts suggested that Mr. Dennis had acted in self defense, he was quickly arrested and arraigned on assault charges.

In the racial caste system of this era, white lives and white property had heightened value compared to the lives of Black people. In an unusual development for the era, Mr. Dennis was convicted, but received a $25 fine rather than prison time. The mob raided Mr. Rucker’s home and terrorized his family. Racial terrorism sought to maintain white supremacy by instilling fear in the entire Black community through brutal violence that was often unpredictable and life-threatening to any Black person in a mob’s path.

Beyond questioning the terrified Rucker family and asking the governor to offer a reward for information, records indicate that officials made very little effort to conduct their own investigation into who killed Mr. Dennis. Like most documented lynching victims, Mr. Dennis was killed by a white mob who never faced prosecution.

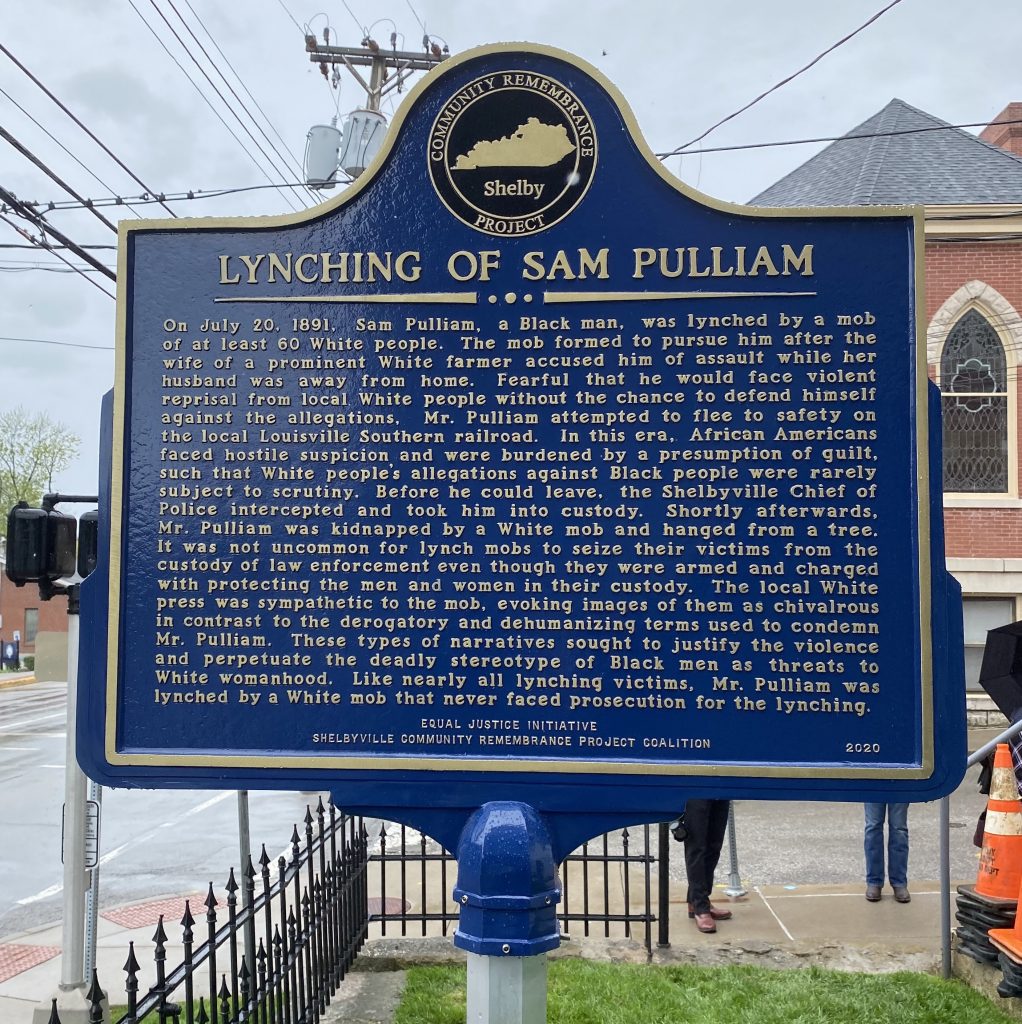

Lynching of Sam Pulliam

On July 20, 1891, Sam Pulliam, a Black man, was lynched by a mob of at least 60 white people. The mob formed to pursue him after the wife of a prominent white farmer accused him of assault while her husband was away from home. Fearful that he would face violent reprisal from local white people without the chance to defend himself against the allegations, Mr. Pulliam attempted to flee to safety on the local Louisville Southern railroad.

In this era, African Americans faced hostile suspicion and were burdened by a presumption of guilt, such that white people’s allegations against Black people were rarely subject to scrutiny. Before Mr. Pulliam could leave, the Shelbyville Chief of Police intercepted him and took him into custody. Shortly afterwards, Mr. Pulliam was kidnapped by a white mob and hanged from a tree. It was not uncommon for lynch mobs to seize their victims from the custody of law enforcement even though they were armed and charged with protecting the men and women in their custody.

The local white press was sympathetic to the mob, evoking images of them as chivalrous in contrast to the derogatory and dehumanizing terms used to condemn Mr. Pulliam. These types of narratives sought to justify the violence and perpetuate the deadly stereotype of Black men as threats to white womanhood. Like nearly all lynching victims, Mr. Pulliam was lynched by a white mob that never faced prosecution for the lynching.

Lynchings of Eugene Marshall and Wade Patterson

In the early morning of January 15, 1911, a white mob abducted three Black men named Eugene Marshall, Wade Patterson, and Jim West from the Shelby County Jail. Although reports indicate that police were aware of the threat of mob violence, law enforcement failed to intervene to prevent the lynching. During this era, police almost never used force to resist white lynch mobs intent on killing Black people, and it was common for mobs to seize their victims from police custody.

The mob dragged the three men to a bridge over Clear Creek and hanged Mr. Marshall and Mr. Patterson. The rope broke as they were hanging Mr. Patterson, so they severely beat him and shot him to death. Mr. West was injured by the mob, but he was able to escape and reportedly fled the county. Later that morning, Mr. Marshall’s body was found hanging from the bridge and Mr. Patterson’s body was found nearby in the creek.

The three men had been accused of separate offenses. Mr. Patterson and Mr. West were accused of offenses against white women at a time when the mere accusation of violence against white women aroused violent mobs. Although Mr. Marshall was accused of killing a Black woman, local accounts indicate he was lynched likely as the result of the mob mistaking his identity.

Soon after the lynchings, local authorities initiated a grand jury investigation. Despite the uncommon calls for accountability, no one was held responsible for the lynchings.

Lynchings of Clarence Garnett and Jimbo Fields

On October 2, 1901, a mob of armed white men hanged 19-year-old Clarence Garnett and 15-year-old Jimbo Fields, African American teenagers, from the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad trestle over Clear Creek. The two young men had been accused of murdering a white man who drunkenly tried to enter Jimbo’s home. Police arrested them and held them at the Shelby County Jail. A white mob intent on lynching both of them entered the unguarded jail, broke down the door, and abducted them.

During this era, African Americans faced hostile suspicion and were burdened by a presumption of guilt, that often resulted in fatal violence before an investigation or trial. After kidnapping Jimbo and Clarence, the mob marched them 500 yards to the site of their deaths. Later, a Black man incarcerated at the jail reported that he knew some of the mob participants but had been threatened into silence. Jimbo’s mother was threatened by the mob to leave town. These types of threats of violent retaliation were meant to intimidate people to ensure the mob would not be held accountable.

Like nearly all victims of racial terror lynching, Clarence and Jimbo were killed by a white mob that never faced prosecution. Memorializing these victims of racial terror lynchings is critical in addressing our nation’s history of racial injustice and in advancing the continuing struggle for equality and the elimination of bias and bigotry.

/

Shelby County residents attend the marker unveiling ceremony on April 10, 2021.

/

/

Members of the Shelbyville Community Remembrance Project, Shelby County community members, and EJI staff at the the marker unveiling ceremony on April 10, 2021.

/

Shelbyville Community Remembrance Project Coalition

The Shelbyville Community Remembrance Project Coalition (SCRPC) formed in 2018 after members organized a trip to EJI’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The core group includes the Shelbyville Area NAACP Branch, the Greater Shelby County Ministerial Coalition, the First Presbyterian Church, First Christian Church, and the Shelby County Historical Society.

After learning about the lynchings of six Black people in Shelby County, the group decided to pursue Community Remembrance Projects to preserve the victims’ memory and advance the work of true justice in their community. The Shelbyville Community Remembrance Project Coalition believes in bringing light to some of the deep, dark tragedies that this community has faced and talking about how to move forward as a community in peace and unity. Their goal is not only to increase awareness of racial terror lynchings in the region, but also to help people learn of the harmful effects on those involved, their offspring, and the community.

On September 28, 2019, the coalition hosted a soil collection ceremony to memorialize Ruben Dennis, Sam Pulliam, Jimbo Fields, Clarence Garnett, Eugene Marshall, and Wade Patterson. The jars of soil are on display at the Shelby County Historical Society and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery. The coalition remained committed to ongoing research and intentional community coalitionbuilding throughout 2020, despite the difficulties of navigating the Covid-19 pandemic.

Lynching in America

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. After slavery ended, many white people remained committed to racial hierarchy and used lethal violence and terror against Black communities to maintain a racial, economic, and social order that oppressed and marginalized Black people. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and created a legacy of injustice that can still be felt today.

Of the hundreds of Black people lynched under accusation of alleged crimes, nearly everyone was brutally killed without being legally convicted of any offense. Many African Americans were lynched for perceived violations of social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or being accused of crimes even when there was no evidence tying the accused to any offense. White mobs regularly displayed complete disregard for the legal system, seizing their victims from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or from police custody without fear of legal repercussions for the lynchings that followed. In this environment of official indifference, racial terror remained systematic, far-reaching, and devastating to the Black community for generations.

Although many victims of racial terror lynching will never be known, at least 169 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Kentucky between 1877 and 1950, with at least six victims in Shelby County.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. The narrative historical markers in Shelbyville are among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI to date.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.