The Alachua County Community Remembrance Project partnered with EJI to dedicate a historical marker in memory of nine documented victims of racial terror lynching in Newberry, Florida. The marker was unveiled at a dedication ceremony on August 21 at Freddie Warmack Park, the former site of the segregated school for Black children.

The area where the marker stands is known locally as “Lynch Hammock” and “Hangman’s Island” because it was the site of multiple lynchings, including the documented mass lynching of at least six Black men and women on August 18 and 19, 1916, and the lynching of a Black man named Abraham Wilson on January 17, 1923.

Oral history suggests that a Black man named Dick Johnson as well as other unidentified Black victims were also lynched there in August 1916 and that additional undocumented lynchings occurred in this area. Manny Price and Robert Scruggs, two Black phosphate mine workers who were lynched by a white mob on September 1, 1902, are memorialized on the historical marker as well.

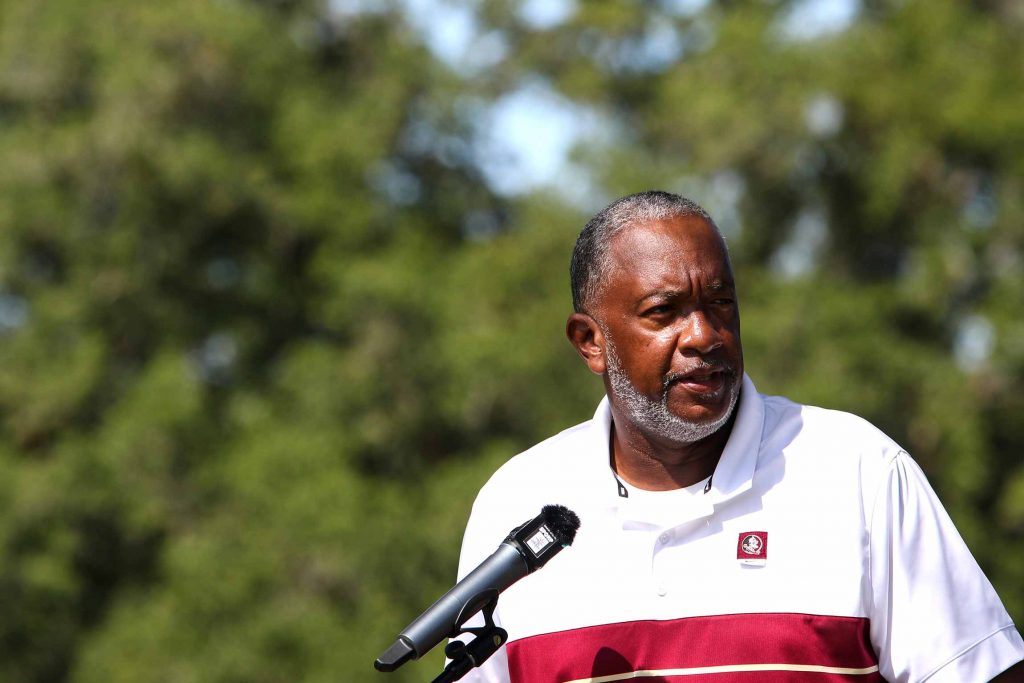

Community members from throughout the county, including faith leaders, educators, artists, local researchers, and youth, gathered to dedicate the historical marker. During the ceremony, Warren Lee, great-great-grandson of James Dennis, who was lynched in Newberry on August 18, 1916, spoke about his grandmother, who recounted the lynchings she witnessed. “She said, ‘Listen, I’m telling you this. I want you to do something with it. You need to talk about it. You need to tell people about it.’” Mr. Lee honored the late Dr. Patricia Hilliard-Nunn, who conducted extensive research on racial terror in Alachua County and encouraged him to participate in oral history interviews about his family’s experience.

Mayor Jordan Marlowe, who spearheads the coalition’s efforts in Newberry, read a proclamation marking the lynchings as the darkest period of the city’s history.

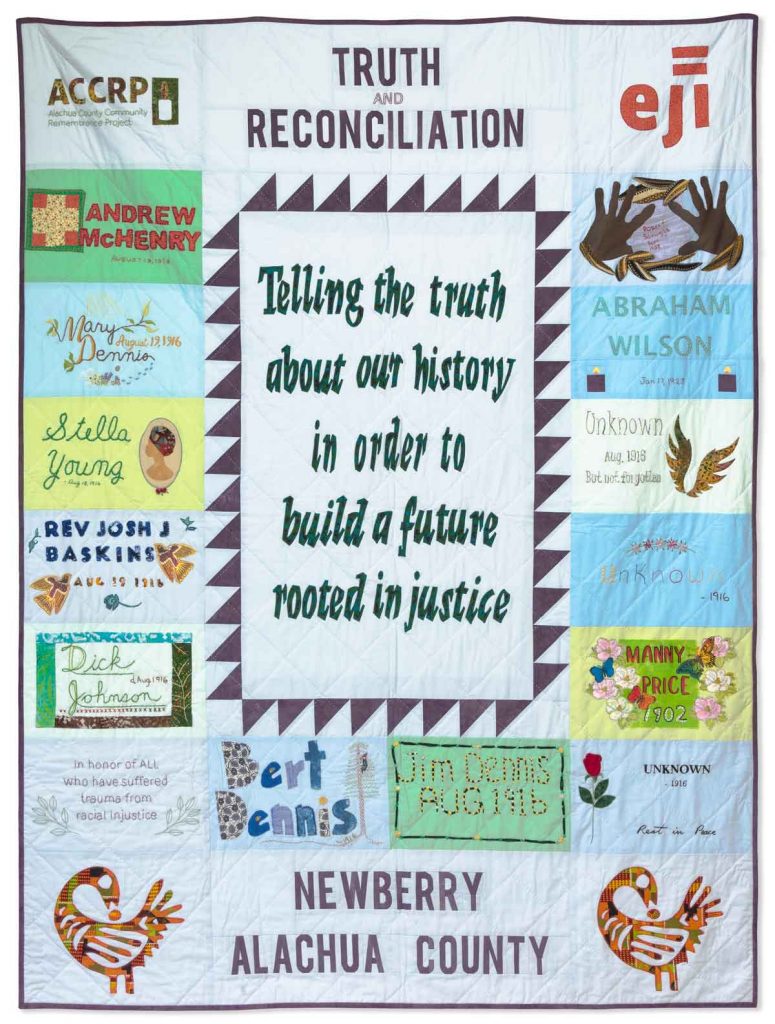

The historical marker dedication also included the unveiling of a new traveling exhibit that contains jars of soil collected from the site of the 1916 lynchings. The exhibit will be displayed at locations throughout the county to continue educating community members about the local history of racial terror. The day before the dedication ceremony, a Black art show featured a quilt made by members of the Alachua County Community Remembrance Project in memory of all documented and undocumented victims of racial terror lynching in Newberry.

Lynchings in Newberry

After the Civil War, emancipated Black people in Alachua County bought their own land and established a rural farming community from Jonesville to Newberry with farms, churches, a school, and local businesses.

Many white residents violently resisted racial equality and terrorized Black people to enforce Jim Crow segregation and racial hierarchy.

On September 1, 1902, a mob of 300 white men seized two Black mine workers, Manny Price and Robert Scruggs, from law enforcement, hanged them, and riddled their bodies with bullets.

Fourteen years later, on August 18 and 19, 1916, white mobs that included a state senator, local sheriff, community leaders, and well-known citizens lynched six Black men and women from Jonesville after a Black farmer was accused of mortally wounding a Newberry constable. A mob abducted Jim Dennis from his home and shot him to death while another mob hanged Bert Dennis, Mary Dennis, Stella Young, Andrew McHenry, and the Reverend Josh Baskins in Newberry. These events are often referred to as “The Newberry Six” lynchings, but oral history suggests that a Black man named Dick Johnson and two unidentified Black victims were also lynched during this bloody weekend.

Seven years later, in January 1923, white mobs killed at least seven Black people in Rosewood, Florida, in neighboring Levy County about 40 miles from Newberry, after a white woman alleged she had been sexually assaulted by a Black man. During the widespread racial terror violence that became known as the Rosewood Massacre, a white mob in Newberry abducted Abraham Wilson, who had been jailed for allegedly stealing cattle, and lynched him on January 17.

No one was held accountable for any of these murders.

Alachua County Community Remembrance Project

In 2019, community members across Alachua County came together to form the Alachua County Community Remembrance Project after the Board of County Commissioners in June 2018 began discussing a truth and reconciliation process to address the local history of racial injustice. Coalition members took a community trip to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and decided to include projects to memorialize the dozens of victims of racial terror lynchings in the county as part of these county-wide truth and reconciliation efforts.

Members of the coalition include local researchers, educators, faith leaders, public officials, community activists, and other concerned citizens who are helping to advance local remembrance efforts. The coalition consists of regional subcommittees throughout the county, including the areas of Newberry, Gainesville, Alachua-Newnansville, Archer, High Springs, Micanope, Hawthorne, Waldo, Monteocha, Gordon, and Lacrosse.

In addition to soil collection ceremonies, the coalition recently hosted an EJI Racial Justice Essay Contest for high school students in Gainesville and is working towards the dedication of multiple historical markers. They continue to host a variety of public education events, including book reads, film screenings, panel discussions, story-telling events, art contests and shows, and oral history projects.

/

Warren Lee, great-great-grandson of James Dennis, who was lynched in Newberry in 1916, speaks during the marker dedication ceremony.

Sam Thomas/The Gainesville Sun

/

Jars with soil collected from the site of the 1916 lynchings now sit in a traveling soil exhibition, which was unveiled along with the historical marker.

Sam Thomas/The Gainesville Sun

/

A quilt made by members of the Alachua County Community Remembrance Project in memory of victims of racial terror lynching in Newberry.

/

Lizzie Jenkins hugs Warren Lee after the marker dedication ceremony.

Sam Thomas/The Gainesville SunLynching in America

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. After slavery ended, many white people remained committed to racial hierarchy and used lethal violence and terror against Black communities to maintain a racial, economic, and social order that oppressed and marginalized Black people. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and created a legacy of injustice that can still be felt today.

Of the hundreds of Black people lynched under accusation of alleged crimes, nearly everyone was brutally killed without being legally convicted of any offense. Many African Americans were lynched for perceived violations of social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or being accused of crimes even when there was no evidence tying the accused to any offense. White mobs regularly displayed complete disregard for the legal system, seizing their victims from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or from police custody without fear of legal repercussions for the lynchings that followed. In this environment of official indifference, racial terror remained systematic, far reaching, and devastating to the Black community for generations.

Although many victims of racial terror lynching will never be known, at least 350 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Florida between 1865 and 1950, with dozens of victims killed in Alachua County.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. The narrative historical marker in Newberry is among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI to date.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.