Today, 121 years after John Henry James was lynched near Charlottesville, Virginia, in Albemarle County, community members and officials are unveiling a historical marker recognizing the lynching. The marker dedication is part of the community’s multi-year engagement with EJI’s Community Remembrance Project.

Last summer, dozens of activists, clergy, historians, elected officials, and students gathered soil during a ceremony in a grove of trees near the railroad tracks where Mr. James was pulled from a train. Three glass jars were filled with soil: one each for display in Albemarle County, the City of Charlottesville, and EJI’s Legacy Museum.

Over 100 Charlottesville residents, including city council members, Mayor Nikuyah Walker (the first Black woman to serve as the city’s mayor), and the mother of Heather Heyer, who died while protesting a white nationalist rally in 2017, then traveled by bus to bring the jar of soil to Montgomery. They honored Mr. James with a ceremony at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, where his name is inscribed, and met with EJI director Bryan Stevenson for a discussion about the importance of recognizing our history of racial injustice.

“Even though it’s complicated,” Mr. Stevenson told the group, “there is something better waiting for us in this country, but we can’t get there if we stay silent about this history.”

Elected officials, community leaders, and residents from Charlotteville and Albemarle County have continued the urgent conversation started last summer. Yesterday, they hosted a panel discussion about how monuments impact public spaces and shape the racial narrative of the community.

Virginia Senator Jennifer McClellan, who introduced a resolution acknowledging racial terror lynchings in Virginia, spoke at the panel discussion last night. Under the resolution, which passed unanimously in February, the state’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources will document each lynching in Virginia, and the state will memorialize the lynchings online and with historical markers. The first marker was unveiled in Charles City County in April, acknowledging the lynching of Isaac Brandon, a 43-year-old father of eight who was seized by a mob from the courthouse jail and hanged from a nearby tree in 1892.

Hundreds of people, including Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, joined local officials, community organizers, residents, and EJI staff for the marker unveiling ceremony today, which featured remarks from Charlottesville Mayor Nikuyah Walker, Albemarle County Supervisor Diantha McKeel, and Jefferson School executive director Dr. Andrea Douglas, and a reading by University of Virginia professor Dr. Jalane Schmidt. Siri Russell, the Director of the Albemarle County Office of Equity and Inclusion, unveiled the marker.

The Lynching of John Henry James

In 1898, John Henry James, an African American man, was working as an ice cream vendor in Charlottesville, Virginia, where he had lived for about five years.

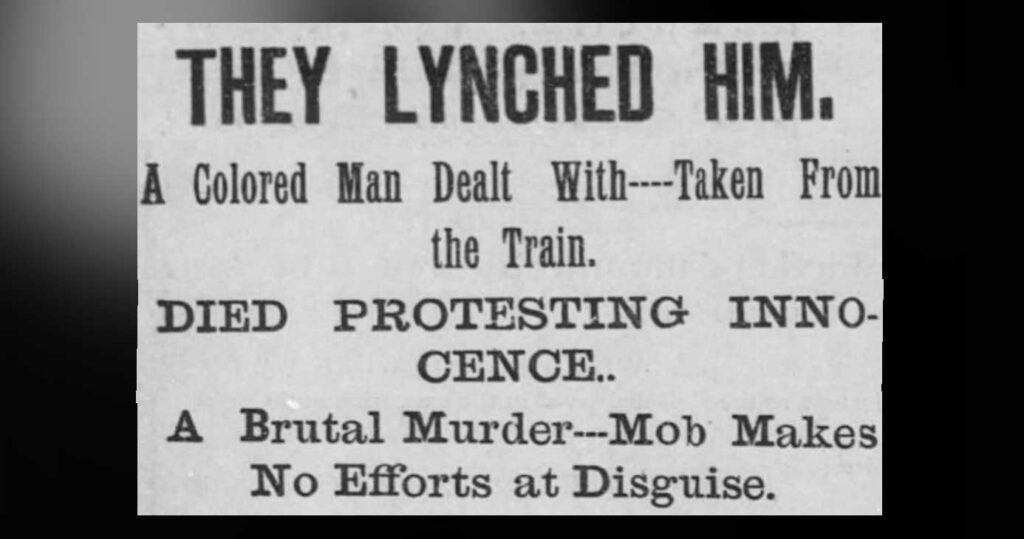

On July 11, he was arrested after being falsely accused of assaulting a white woman. Police took him to Staunton that evening to avoid a potential lynching, but officers escorted him back to Charlottesville the next morning by train. An armed mob of 150 white men stopped the train at Wood’s Crossing in Albemarle County and seized Mr. James. A group of Black men tried to stop the lynch mob but were outnumbered and forced to retreat.

The white mob threw a rope over Mr. James’s neck and dragged him about 40 yards away to a small locust tree. He protested that he was innocent, but the mob hanged Mr. James and fired dozens of bullets into his body.

The Richmond Planet, an African American newspaper, reported that, as his body hung for many hours, hundreds more white people streamed by and cut off pieces of his clothing, his body, and the locust tree to carry away as souvenirs.

A grand jury session was interrupted by news of the lynching and, despite knowing that Mr. James had been killed, it indicted him for assault.

The Charlottesville police chief and Albemarle County sheriff were present at the lynching, but no one was ever charged or held accountable for the murder of John Henry James.

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of its effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. EJI believes that by reckoning with the truth of the racial violence that has shaped our communities, community members can begin a necessary conversation that advances healing and reconciliation.

/

/

/

Lynching in America

Thousands of Black people were the victims of lynching and racial violence in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The lynching of African Americans during this era was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching was most prevalent in the South, including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. After the Civil War, violent resistance to equal rights for African Americans and an ideology of white supremacy led to violent abuse of racial minorities and decades of political, social, and economic exploitation.

In an expanded edition of Lynching in America, EJI also documented racial terrorism beyond Southern borders, detailing more than 300 lynchings of Black people in eight states with high lynching rates in the Midwest and the Upper South, including Oklahoma, Missouri, Illinois, West Virginia, Maryland, Kansas, Indiana, and Ohio.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many Black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known, but EJI has documented 84 racial terror lynchings in Virginia alone between 1877 and 1950.