Lynching in America: Outside the South

More than 300 racial terror lynchings took place outside the South.

Lynching of African Americans was terrorism—a widely supported phenomenon used to enforce racial subordination and segregation. Lynchings were violent and public events that traumatized Black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials.

In Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, EJI documents over 4400 people who were killed in racial terror lynchings in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950.

But racial terror lynchings were not confined to the South.

In 2017, we supplemented the report with racial terror lynchings in states outside the South. We found these acts of violence were most common in Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, and West Virginia.

Sam Bush, Illinois

On May 30, 1893, a white woman claimed she had been assaulted by a Black man in Mount Zion Township, Illinois. On June 2, 1893, Sam Bush was arrested for this alleged offense and placed in jail in Decatur, Illinois. Within hours, a mob of white people began to gather at the local jail.

At 2:00 a.m. on June 3, 25 unmasked white men rushed the jail and began to batter down the door. The 12 guards who were assigned to defend the jail did nothing to resist the mob. After gaining entry, the mob found Mr. Bush, who informed them, “Gentlemen, you are killing an innocent man.” Undeterred, the mob dragged him from his cell and pulled him into the street, where the crowd had grown to 1500 people.

The mob took Mr. Bush down the street to a prominent corner in front of the courthouse, stripped him of his clothes, and placed a rope around his neck. He was given a chance to pray, but the mob became impatient and demanded that he be hanged at once. The mob cut off his prayers and strung him up. He was pronounced dead at 3:07 a.m. His body was cut down shortly thereafter. Members of the mob cut up the rope used to hang him and kept the pieces as souvenirs.

Scott Burton and William Donegan, Illinois

On August 14, 1908, violence erupted just miles from the longtime home of Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, when a mob of white men planning to kidnap and lynch two Black men accused of raping a white woman learned that the men had been moved from the local jail to another city. The white mob descended upon Springfield’s Black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses and stealing almost $150,000 worth of property.

During the riot, which left an estimated seven people dead, hundreds of Black citizens sought National Guard protection at nearby Camp Lincoln and others fled the city. The violence climaxed early the next morning with the public lynching of two Black men who had nothing to do with the original alleged crime. Scott Burton tried to defend himself against the attackers and was shot four times, dragged through the streets, then hung and mutilated until the national guard interceded. William Donegan, an 84-year-old Black man who was married to a white woman, was taken from his home and hung from a tree across the street, where his assailants cut his throat and stabbed him. Mr. Donegan was still alive when militia arrived at the scene but died the next morning.

Police arrested 150 white people suspected of participating in the violence and 117 were indicted. Three people were indicted for murder; one committed suicide and two were acquitted.

In September, Nellie Hallam, the alleged rape victim whose accusations set off the wave of violence, signed an affidavit stating that neither of the Black men initially accused had attacked her. She said her attacker was a white man and she refused to identify him.

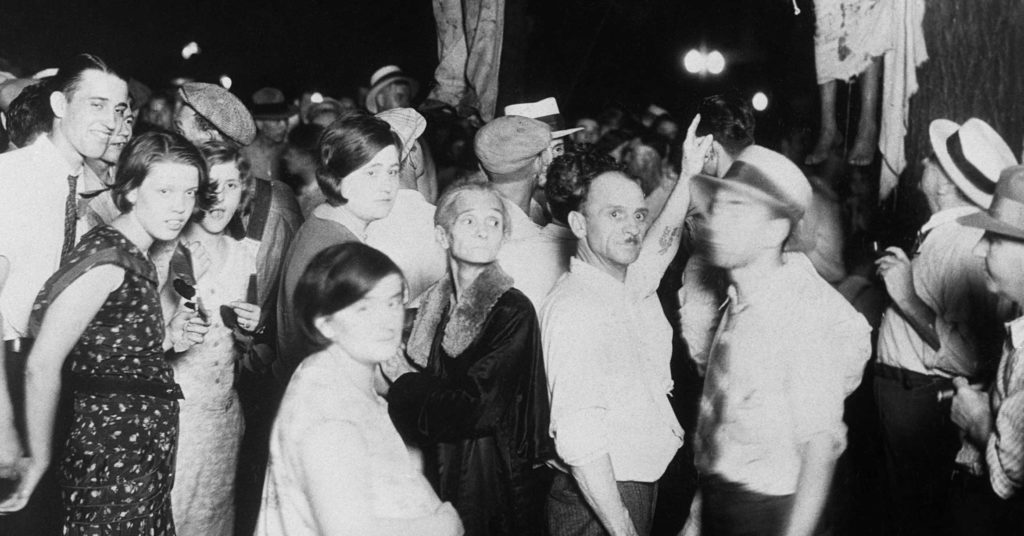

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, Indiana

On August 7, 1930, a large white mob used tear gas, crowbars, and hammers to break into the Grant County jail in Marion, Indiana, to lynch three young Black men who had been accused of murdering a white man and assaulting a white woman. Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, both 19 years old, were severely beaten and lynched, and 16-year-old James Cameron was badly beaten but survived.

The brutalized bodies of Mr. Shipp and Mr. Smith were hung from trees in the courthouse yard and kept there for hours as a crowd of white men, women, and children grew by the thousands. Public spectacle lynchings, in which large crowds of white people, often numbering in the thousands, gathered to witness and participate in pre-planned heinous killings that featured prolonged torture, mutiliation, dismemberment and/or burning of the victim, were common during this time. When the sheriff eventually cut the ropes off the corpses, the crowd rushed forward to take parts of the men’s bodies as souvenirs.

Photographs of the brutal lynching, featuring members of the crowd proudly posed beneath the hanging corpses, were widely shared, but local authorities claimed no one could be identified. Mounting outside pressure eventually led to the trial of two accused mob leaders, each of whom was found innocent by juries of all white men.

The alleged assault victim, Mary Ball, testified years later that she had not been raped.

Bud Rowland, Jim Henderson, and John Rolla, Indiana

On December 16, 1900, a white barber was murdered in Rockport, Indiana. Suspicion immediately fell on two Black men, Bud Rowland and Jim Henderson, who were arrested and placed in the local jail. Within hours of their arrest, a mob of at least 1000 white people came to the jail with sledgehammers, ropes, and guns, to kidnap and lynch these two men. The mob took down a telegraph pole and used it as a battering ram to cave in the wall of the jail.

The mob first removed Mr. Rowland from his cell, placed a rope around his neck, and took him to the east side of the courthouse lawn. Mr. Rowland allegedly implicated Mr. Henderson and a third Black man, “Whistling Joe,” in the murder. The mob then hung him from a tree and fired bullets into his body. The mob returned to the jail, shot Mr. Henderson in his cell, and then dragged his body to the courthouse lawn and hung him from the same tree as Mr. Rowland, and shot bullets into his body as well.

The mob then went after John “Whistling Joe” Rolla, who was employed at a local hotel. The mob was initially turned back because Mr. Rolla’s employer provided him with an alibi, but Mr. Rolla was arrested later that night and taken to neighboring Boonville, Indiana. The following evening, a white mob of 100 Rockport citizens, broke into the jail in Boonville and kidnapped Mr. Rolla, as he pleaded his innocence. The mob took him to the courthouse lawn in Boonville and hung him from a tree. No one in the mob wore a mask.

Fred Alexander, Kansas

In 1899, Fred Alexander returned home to Leavenworth, Kansas, after serving in the Spanish-American War. In 1900, the body of a 19-year-old white woman, Pearl Forbes, was found in a nearby ravine. Though local police believed that Ms. Forbes was killed during a robbery gone awry and a medical examination showed that she had not been sexually assaulted, a coroner’s jury declared without any basis that she had been strangled “for the purpose of rape.” The jury searched for a suspect for months before another white woman, Eva Roth, accused Mr. Alexander of assaulting her. He was quickly arrested for both crimes.

On January 15, 1901, a mob of thousands broke into the jail and attacked Mr. Alexander with a hatchet before dragging him from his cell. In the gruesome lynching that followed, the white mob mutilated Mr. Alexander. They castrated him, likely while he was still alive, and took parts of his body as souvenirs. The mob took the dying man to the ravine, chained him to an iron stake, doused him with 22 gallons of kerosene, and set him on fire before the massive crowd.

The local press helped instigate the violence by using racist stereotypes to stir fear and hatred among the local white community. This public spectacle lynching was was one of 19 recorded terror lynchings in Kansas between 1877 and 1950.

George Armwood, Maryland

George Armwood, a 23-year-old mentally ill Black man, was accused of attacking an elderly white woman, and was arrested. State police moved him to three different jails before he was brought to Somerset County based on reassurances from officials there that he would be safe.

On October 18, 1933, shortly after Mr. Armwood was brought to the county jail, a mob of more than 1000 white people began to form. Several members of the mob reportedly had come to the jail earlier in the day to find out where Mr. Armwood was being held. They broke into the jail using 15-foot timbers as battering rams, placed a noose around Mr. Armwood’s neck, dragged him from his cell, and hung him from a nearby tree.

After Mr. Armwood was dead, members of the mob dragged his body down the town’s main street before hanging his body from a telephone pole near the courthouse and setting it on fire.

The Afro American reported that the mob danced around Mr. Armwood’s charred remains. The report quoted one white man, who said, “It would have cost the state $1000 to hang the man. It cost us 75 cents.”

Public square in Springfield.

Horace Duncan, Fred Coker, and Will Allen, Missouri

Two innocent African American men, Horace Duncan and Fred Coker, were accused of sexual assault in April 1906 in Springfield, Missouri. Whites’ fears of interracial sex extended to any action by a Black man that could be interpreted as seeking or desiring contact with a white woman. Local publications agitated racist sentiments by blaming rising crime in Springfield on Black residents. Though both men had alibis confirmed by their employers, a mob refused to wait for a trial. Instead, the mob used sledgehammers, telephone poles, and other tools of demolition to gain entry into the men’s jail cells.

Just before midnight on April 14, they hanged Mr. Duncan and Mr. Coker from a light tower in the town square and burned and shot their corpses while a crowd of 5000 white people participated. Newspapers later reported that both men were innocent of the rape allegation.

Continuing their string of violence into the early morning of April 15, the mob chased after Will Allen, who had been accused of a recent murder without evidence. He tried to hide from the mob, but was kidnapped and hanged from the same tower in the town square. Police and county officials did not act to prevent any of these lynchings.

William Godley, French Godley and Peter Hampton, Missouri

Whites’ hypervigilant enforcement of the racial hierarchy and wildly distorted fear of interracial sex permeated society at the turn of the century. The mere accusation of rape, even without an identification by the alleged victim, often aroused a mob and resulted in lynching.

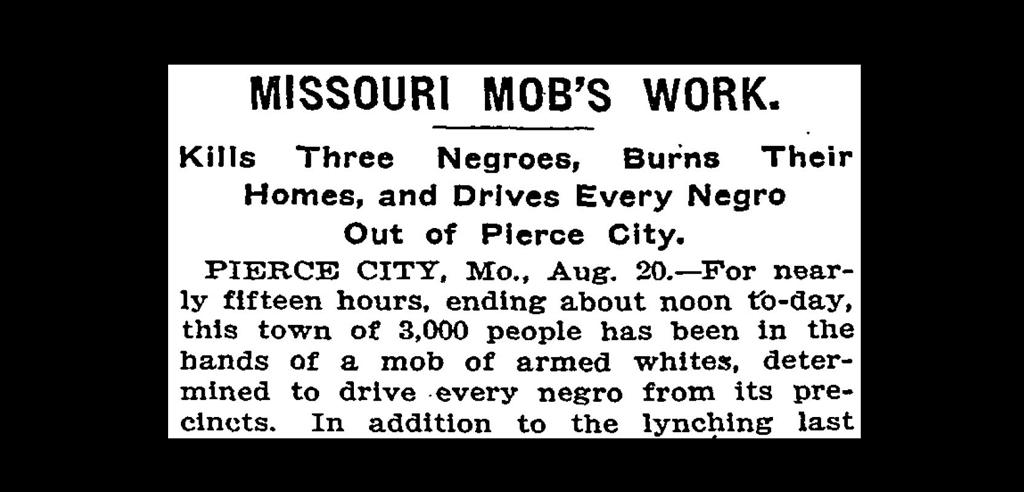

In 1901, the body of a white woman was found in Pierce City, Missouri. The victim had a fractured finger but there was no evidence she had been raped. William Godley, a Black man, was arrested and charged with rape and murder. A conviction ten years earlier for the rape of a white woman, based on a questionable eyewitness identification, had given Mr. Godley a reputation as a sexual aggressor. On August 20, 1901, Mr. Godley was seized from the city jail by a mob of white men and lynched.

Rumors circulated that a Black man had attempted to shoot at the perpetrators during the lynching, and the mob moved from outside the jail to the Black section of Pierce City, where Mr. Godley’s grandfather, French Godley, was shot to death and Peter Hampton was burned alive in his home.

The violence and terror lasted nearly 15 hours. African American residents fled for their lives, and the Black population of Lawrence County declined from 400 at the turn of the century to only 91 people by 1910.

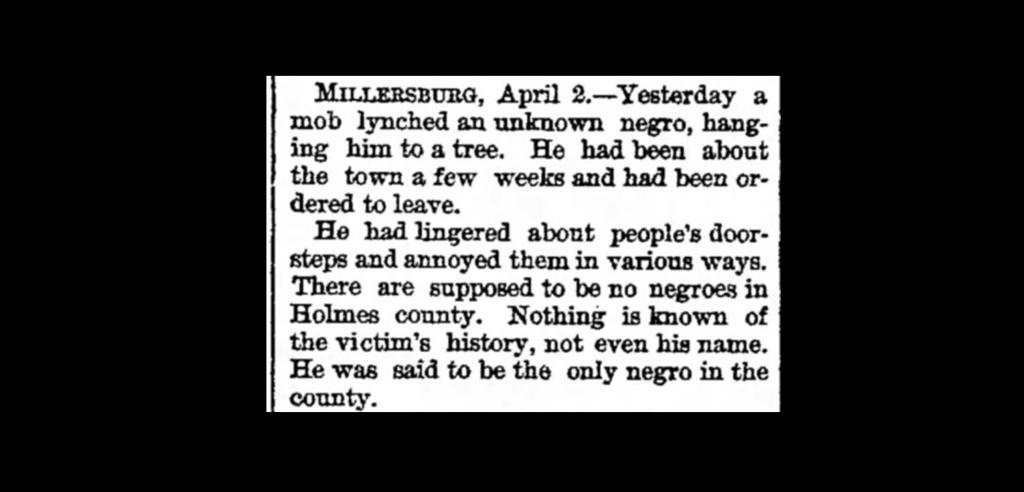

Unknown, Ohio

Lynchings based on minor social transgressions were a tool of racial control designed to enforce social norms and racial hierarchy. Hundreds of African Americans accused of no serious crime were nonetheless lynched for myriad “offenses,” including speaking disrespectfully, refusing to step off the sidewalk, using profane language, using an improper title for a white person, suing a white man, arguing with a white man, bumping into a white woman, insulting a white person, and other social grievances. African Americans were terrorized by the knowledge that they could be lynched if they intentionally or accidentally violated any social more defined by any white person.

In the spring of 1892, a Black man from Mt. Vernon or Wooster, Ohio, whose name remains unknown, was walking in Holmes County, an all-white county. After he had been in town for a few days, a group of white people decided to lynch him because he “lingered about people’s doorsteps and angered them in various ways.” On April 1, 1892, a mob gathered after nightfall, abducted the man, and hanged him from a tree in the public square in front of the county courthouse.

Laura and L.D. Nelson, Oklahoma

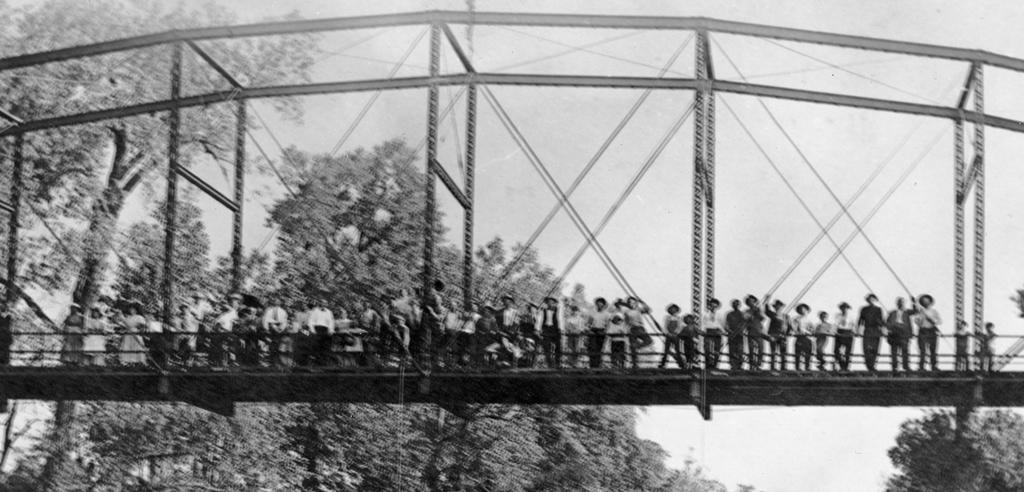

On May 25, 1911, Laura Nelson, an African American woman, and her teenaged son, L.D., were kidnapped from the Okemah County jail in Oklahoma before they could stand trial on murder charges. Ms. Nelson and her son were accused of killing a deputy sheriff while he was searching their cabin for stolen meat, but the prosecution’s presentation at the preliminary hearing raised doubts about whether the State had sufficient evidence for a conviction.

Members of the white mob reportedly raped Ms. Nelson before hanging her and her son from a bridge over the Canadian River, close to the Black part of town. Choosing that site sent a message of terror and intimidation to the entire Black community. The next morning, hundreds of white people from Okemah came to view the bodies. Photographs of the spectacle were later reprinted as postcards and sold at novelty stores.

A special grand jury was called to investigate the lynching. District Judge Caruthers instructed the jurors to be mindful of their duty as members “of a superior race and greater intelligence to protect this weaker race.” No member of the mob was prosecuted.

Tulsa Massacre, Oklahoma

Racial terror lynching is defined as the extrajudicial killing of one or more Black people by white mobs or entire communities with little to no accountability for the perpetrators. The Tulsa Massacre of 1921 led to the deaths of at least 36 Black Tulsans and the destruction of the Black community.

On May 31, 1921, Dick Rowland, a Black 19-year-old shoe shiner, was jailed in the Tulsa County Courthouse after a white woman reported he assaulted her. The charges were dropped, but police kept him in the courthouse to protect him from a growing white mob that sought to lynch him. Members of the Black community also stationed themselves in the courthouse to protect Mr. Rowland from a potential lynching.

Thousands of white people joined the mob. Reports show that local authorities provided firearms and ammunition to the white rioters, who began to shoot at the men protecting Mr. Rowland, forcing them to retreat to Greenwood, a Black neighborhood anchored by a thriving Black business district. The white mob, including city-appointed deputies, followed and terrorized Greenwood, shooting indiscriminately at any Black person they saw and burning homes and buildings. Numerous survivors reported that planes from a nearby airfield dropped firebombs on Greenwood. The Oklahoma National Guard was dispatched the next day to suppress the violence, but they treated the attack as a “Negro uprising” and arrested hundreds of Black survivors. No members of the white mob, local government, or national guard were prosecuted or punished.

Over 10,000 Black people were displaced from their community. Several hundred Black people were likely killed, but there is no reliable account of the casualties because public officials did not keep a record of Black people who had been hospitalized, wounded, or killed.

Robert Johnson, West Virginia

In 1912, Robert Johnson, an innocent Black man from Bluefield, West Virginia, was accused of raping a white girl. While he was being held in nearby Princeton, authorities determined that Mr. Johnson had committed no crime and was not guilty of the sexual assault.

On the afternoon of September 5, 1912, a mob from Bluefield cut telephone lines so that no warning could be called ahead, and then traveled to Princeton to abduct Mr. Johnson from the jail. Officers did not prevent them from rushing the jail. Once they captured Mr. Johnson, they hung him by handcuffs from a telephone pole in Princeton, then shot bullets into his body, took his clothing for souvenirs, and paraded around to terrorize the Black community. Five thousand people reportedly participated in the lynching.

Robert Johnson was one of ten known lynching victims in Mercer County, West Virginia. The perpetrators of his lynching went unpunished.