On Saturday, March 18, EJI joined local government officials, church leaders and community members in unveiling a historic marker in LaGrange, Georgia to commemorate the lynchings of African Americans in Troup County. The permanent marker stands at Warren Temple United Methodist Church at 416 E. Depot Street in LaGrange.

Over one hundred community members, including relatives of lynching victims Austin Callaway and Henry Gilbert, attended Saturday’s ceremony. The program, which marked the first public acknowledgement of both men’s violent murders, included remarks from EJI founder Bryan Stevenson, LaGrange Mayor Jim Thornton, Rev. Vincent Dominique of Warren Temple, leaders from the LaGrange First Baptist Church, Troup Together, Troup NAACP, and the families of the late Gene Bowen and Rev. L.W. Strickland.

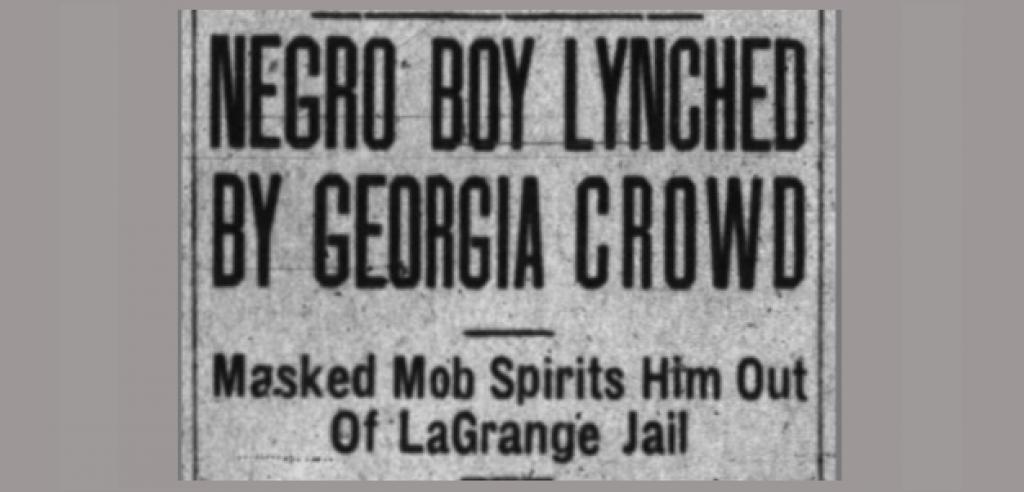

Mayor Thornton apologized on behalf of local authorities and law enforcement for their complicity in past racial terror lynchings. This past January, as the result of community activism and dialogue, the chief of police, mayor and other city leaders formally apologized for the lynching of Austin Callaway.

Lynching in America

Thousands of Black people were the victims of lynching and racial violence in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The lynching of African Americans during this era was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching was most prevalent in the South. After the Civil War, violent resistance to equal rights for African Americans and an ideology of white supremacy led to violent abuse of racial minorities and decades of political, social, and economic exploitation.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many Black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known, but EJI has documented nearly 600 lynchings in Georgia alone.

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project

EJI erects historical markers at lynching sites as part of its Community Remembrance Project, a campaign to recognize the victims of lynching that includes collecting soil from lynching sites and creating a memorial that acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice in America. EJI believes that by reckoning with the truth of the racial violence that has shaped our communities, community members can begin a necessary conversation that advances healing and reconciliation.