New Orleans has always seemed a layered city, where past and present exist within and on top of, rather than before and after. Entangling and conversing across time and space, traversing common streets, alleys, and waterways, comparing music and revelry, violence, and pain. At Canal and Burgundy Streets, 152 years ago this summer, a line of marching Black men beating a drum and hoisting an American flag were a bold and conspicuous and curious scene. The abolition of slavery was barely six months old, Black citizenship was largely new and undefined, and racial tensions were high – yet they marched in a showing of patriotism and hope. And on streets that now form the heart of downtown, their demonstration was met with police brutality and deadly violence.

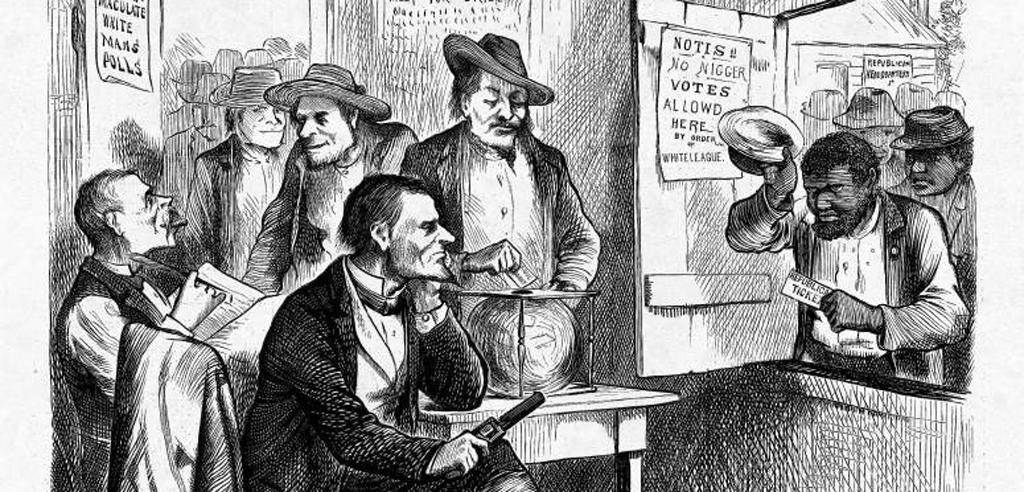

On July 30, 1866, the Civil War was over and former Confederate states were under federal rule. At what is today the Roosevelt Hotel, New Orleans was hosting a convention of white men working to make sure Louisiana’s new constitution would guarantee Black voting rights, and for weeks leading up to the event, local press had denounced the attendees as traitors and invaders. “Within a short time,” warned one newspaper, “we may expect to see the State of Louisiana a member of the Union, with nigger suffrage, nigger Senators, and nigger representatives.” When local Black men staged a march to support the convention, the seething opposition erupted in violence that indiscriminately killed Black people in the area.

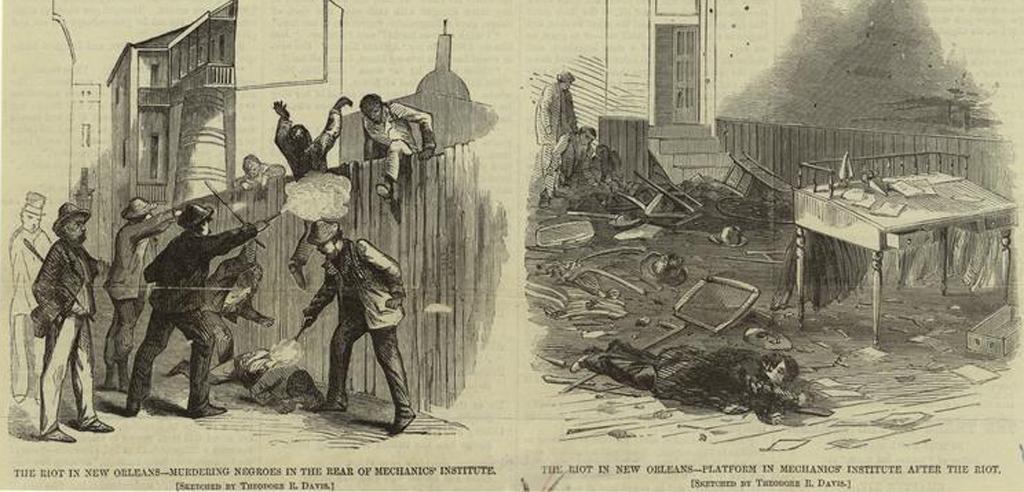

“For several hours, the police and mob, in mutual and bloody emulation, continued the butchery in the hall and on the street, until nearly two hundred people were killed and wounded,” concluded a Congressional committee formed to investigate the massacre. “How many were killed will never be known. But we cannot doubt there were many more than set down in the official list in evidence.”

Nearly two years later, in July 1868, the United States adopted the Fourteenth Amendment, granting citizenship to Black people born in the United States, and in 1870 ratified the Fifteenth Amendment, explicitly prohibiting racial discrimination in voting. But bloody conflicts over voting rights erupted again and again, in the Louisiana communities of Opelousas and Colfax; in Eufaula and Eutaw in Alabama; and throughout the South.

Federal troops abruptly left the region in 1877, and by 1900, Black voters were a rarity. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses reigned for decades until the 1965 Voting Rights Act created federal prohibitions and oversight to eradicate most, but not all, of those suppression tactics. Felony disenfranchisement policies that ban citizens from voting due to past criminal convictions have proved the most enduring and persistent remnant of 19th century voter discrimination efforts – shielded from challenge by the very Fourteenth Amendment recently celebrated for 150 years of ensuring equal justice.

* * *

According to the Sentencing Project, over six million Americans with criminal convictions cannot vote due to a patchwork of laws in 48 of the 50 states. Some disenfranchise only those in prison for a felony, while other states bar from voting anyone on probation or parole. Still others impose waiting periods or other conditions before voting rights can be restored, and a small number permanently prohibit voting after a felony conviction.

Louisiana and Alabama today remain legal and political battlegrounds. The once-controversial question of “Negro suffrage” has given way to debates over the electoral fitness of people with criminal convictions, but the racial results are still striking: 2.2 million Black Americans are disenfranchised – that is one in 13, and four times the rate of all other racial groups combined. In 23 states, including Louisiana and Alabama, at least 5 percent of Black voting-age residents are banned from the ballot box.

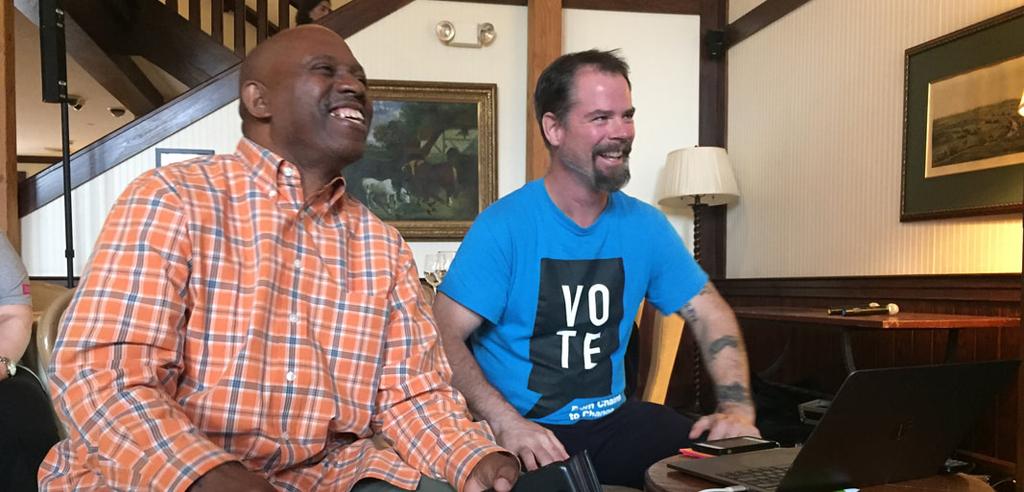

This is also a time of movement. The Louisiana legislature last year enacted reform restoring the vote to those on probation and parole after a waiting period. Voice of the Experienced (V.O.T.E.) helped spearhead this legislative effort over several years, headquartered just two miles from where the New Orleans massacre began. A grassroots organization of formerly incarcerated people, V.O.T.E. built a “people-powered” movement and won an unlikely victory in Louisiana – a state that recently had the highest incarceration rate in the nation.

Just weeks after Louisiana’s governor signed the legislative reform into law, Deputy Director Bruce Reilly described the way V.O.T.E. leveraged its knowledge and connections to directly confront lawmakers with impacted Louisianans’ stories. A transplant from Rhode Island, and himself formerly incarcerated, Reilly recognizes the racial roots of these policies, but also his part in the fight. “A lot of people would see me as a straight, white man who can pass and just leave all this behind,” Reilly said. “I don’t know where I would go to leave this behind. When they run your record and they see that you’re on probation for a Class 1 felony, you’re just back where you started. There’s no opting out of this for me.”

In Alabama, a federal lawsuit scheduled for trial next year is challenging multiple provisions and effects of the state’s disenfranchisement law, while the legislature last year took action to clarify a crucial question long left unanswered: who in Alabama is disenfranchised?

In 1901, delegates convened to write a new Alabama constitution were very clear on whom they wanted to disenfranchise and why. In the words of convention president John B. Knox, the framers aimed, “within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state. If we should have white supremacy, we must establish it by law – not by force or fraud.” The law would have to be less plainspoken, since a racialized disenfranchisement scheme would violate the federal constitution.

The resulting Alabama constitution included a provision declaring that “no person convicted of a felony involving moral turpitude” could vote without having his rights restored. That 1901 Constitution remains in effect today, and the “moral turpitude” language – struck down as intentionally discriminatory in 1985 – was resurrected verbatim in the 1990s. Until this year, the state had never explained its meaning.

“At the time we filed our lawsuit, there was no definition of moral turpitude in the law or issued by the State, so voting rights were subject to arbitrary decision-making by individual registrars,” explained Danielle Lang, deputy counsel at the Campaign Legal Center in Washington, D.C., and a member of the legal team suing Alabama state officials in federal court. “No other state has had as arbitrary and random a system as Alabama had, for as long as it had it. In summer 2017, about nine months after our suit began, the legislature defined moral turpitude for the first time.”

During his 2014 campaign to become Alabama’s secretary of state, John H. Merrill asked county registrars what they needed. The most common request, he recalls, was for help defining moral turpitude and ending the arbitrary, discretionary process that led to varied disenfranchisement decisions from county to county. After his election, Merrill formed a committee to examine the issue and make recommendations, and ultimately drafted a legislative proposal. Passed on its second attempt, the “Definition of Moral Turpitude Act” was signed into law on May 25, 2017.

In a recent interview at the Alabama state capitol, Merrill said that he could not discuss pending litigation, but also noted that he believed the new law may end litigation challenging disenfranchisement in Alabama. Plaintiffs’ counsel Danielle Lang agrees the legislation is “an enormous step forward,” but noted that the new list of “moral turpitude” offenses raises new questions.

“Low-level theft crimes are all included, while bribery, public corruption crimes, many white collar crimes, are not,” Lang explained. “We’re currently analyzing the racial impact of this list, but just on its face – to the extent that disenfranchisement on the basis of criminal conviction is allowed, you would expect that offenses directly related to the democratic system would be among those included if the goal is truly protection of the ballot box.”

Defining the “true goal” remains the heart of the inquiry. No one seems to know precisely how many people the new law enfranchises, or who they are – partly because the former system was so uncertain, but perhaps also due to a lack of state interest. When asked, Merrill said he did not know the law’s numeric effect, and did not care. “My job and my goal as secretary of state is simply to register as many eligible voters as possible, under the law, no matter who they are.”

But when the foundation of a state’s electoral system was explicitly designed to secure white supremacy, it’s not clear that a level playing field is enough to even the score.

“Alabama is no different than basically every Southern state that adopted sweeping disenfranchisement laws during Reconstruction to disenfranchise Black voters,” said Lang. “Felon disenfranchisement is one of the most clear vestiges of Jim Crow that fully survived that era.”

* * *

Within a few years of the massacre in New Orleans, those in favor of full Black citizenship seemed to win the legislative war with passage of the Reconstruction amendments, but Southern white opponents maintained discrimination using racial violence and state legislation.

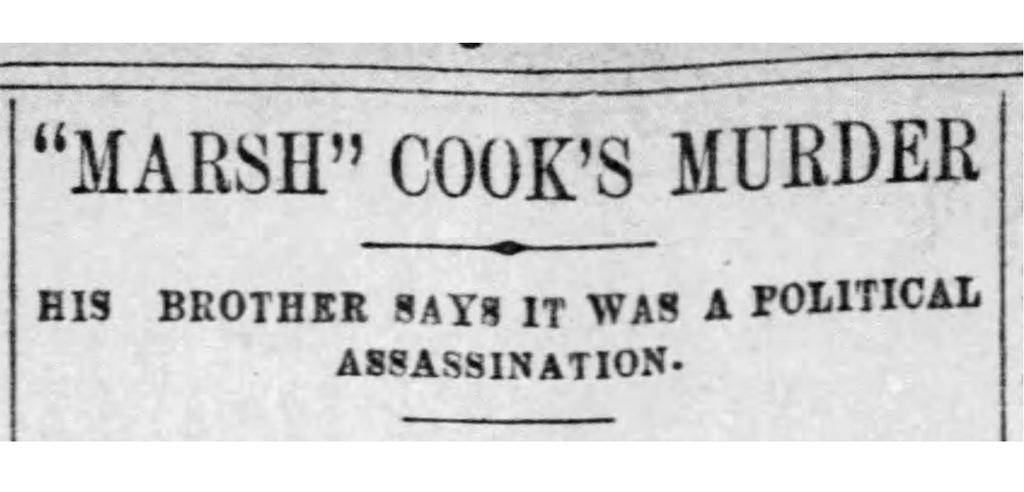

Born into slavery in the 1840s, Jack Turner was an effective organizer of Black voters in Choctaw County, Alabama, before local white political enemies accused him of conspiring to lead a violent attack on local white residents, and lynched him in the Butler town square in 1882. After a Black man named Calvin Mike defied threats and voted in Calhoun County, Georgia, in 1884, white men attacked the family home, killing his mother and two young daughters. And on July 25, 1890, Marsh Cook, a white political candidate who openly advocated for Black voting rights, was shot and killed in Jasper County, Mississippi, by assassins never caught or prosecuted.

“He was considered a firebrand,” one Mississippi newspaper wrote of Cook after his murder, “and after he turned his attention to arraying the Negroes against the whites, few are surprised at his end.”

Upon the 150th anniversary of the Fourteenth Amendment this July, scholars, celebrities, and political leaders lauded its historic and continued promise of “equal protection” and “due process” for all. Few mentioned that, by permitting states to deny the vote for “participation in rebellion or other crime,” Section 2 of the amendment created a gaping constitutional loophole that has maintained felony disenfranchisement as voter suppression’s sturdiest tool.

In Richardson v. Ramirez, a 1977 decision upholding felony disenfranchisement in California, the United States Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly authorizes denying citizens’ voting rights due to criminal conviction – dealing a heavy blow to any hopes of using the Constitution to overturn felony disenfranchisement laws.

“The Fourteenth Amendment is an amendment that was intended to give formerly enslaved people citizenship,” explained Ryan Haygood, a civil rights lawyer who has litigated landmark challenges to disenfranchisement. “But it was also the same amendment that allowed, expressly, for those rights to be withheld if you were convicted of a crime. That conflict is a function of America at once being a place that has very high ideals of freedom and equality, alongside very low practices that undermine the very things that we say we hold dear.”

Ryan Haygood spent 12 years as a litigator with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, where he challenged disenfranchisement laws throughout the country and worked to defend the Voting Rights Act before becoming president of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice in 2015. “I think the Fourteenth Amendment is a mirror reflection of a country that thinks two things at the same time, and has a hard time knowing which one it values more. We’re a place that espouses liberty and justice for all, but we’re also very comfortable not living up to what that means.”

In March 2015, activists with the Formerly incarcerated People’s Movement traveled to Alabama to join events commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery March, and to publicize the continued disenfranchisement of millions of Americans with criminal convictions. (Courtesy of Legal Services for Prisoners with Children)

* * *

When Treva Thompson was convicted of theft of property in Madison County, Alabama, in 2005, Judge Karen Hall’s sentencing order detailed a probation term and suspended imprisonment, but did not mention voting. More than a decade later, Thompson’s sentence is complete but it is uncertain if she will ever vote again. The new list of moral turpitude offenses passed by the legislature last year includes theft, and until Thompson pays the more than $40,000 owed on her case, she cannot even apply to have her rights restored.

“Alabama explicitly hinges your ability to restore your rights on whether you’re able to pay all fines and fees,” said Danielle Lang, legal counsel for Thompson and other plaintiffs challenging the law in federal court. “That goes to the core of voting rights jurisprudence from 1960s onward. Wealth cannot be a determining factor. It is just a vestige of the poll tax.” Even if Thompson were able to overcome the economic hurdle to seek restoration, the process is long and uncertain; in 2014, the most recent year with available data, the state received 2653 applications to restore voting rights, and rejected more than two out of three.

Bruce Reilly of V.O.T.E. became politically active while serving 12 years in prison in Rhode Island, and continued that work after his release. He helped end felony disenfranchisement in Rhode Island with a ballot initiative passed in 2006. Inspired, enfranchised, and a new father, Reilly applied to law school and gained acceptance to Tulane in New Orleans. Cross-country relocation is a daunting task for most, but for Reilly, a move to Louisiana would also mean losing the vote – again.

“I was still on probation at that point. I did five years of parole and then switched over on probation, which I’m still on today for another 15, 20 – I don’t know, a bunch of years,” Reilly recently explained by phone. “I thought it was interesting that a guy that helped win his own re-enfranchisement in one state would lose it by going to law school.”

Though the new Louisiana law will enfranchise Reilly and many others on probation and parole when it goes into effect next year, V.O.T.E. is working with attorneys to litigate a broader challenge to Louisiana’s disenfranchisement law, and trying to help build a political identity among formerly incarcerated people in Louisiana.

Bruce Reilly readily admits he never registered to vote before losing the right at age 20, but now works to restore voting rights for himself and others because he understands the strength of an empowered voting bloc. “I look at the thousands of people who will be able to vote through the new law and I think, how many people are going to know about this or care about this? I was living that life too. I get it. But now I also get, we’re stronger together than apart.”

Attorney Ryan Haygood has spent much of his career defending voting rights, but recalls learning the meaning of political participation firsthand as a child accompanying his mother to vote. “Voting is a learned behavior,” he said. “These laws foster a culture of political non-participation. If your mother or father can’t vote, they don’t teach you to vote, and they’re not passing along that knowledge and identity. That normalizes and encourages inaction.”

Laws that are at once unclear and severe may provide even greater incentive to bypass the ballot box. In a recent case, a Black woman in Texas was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for casting a ballot in the 2016 election while on probation. The woman, who is currently appealing her conviction and sentence, has insisted she did not know she was legally barred from voting.

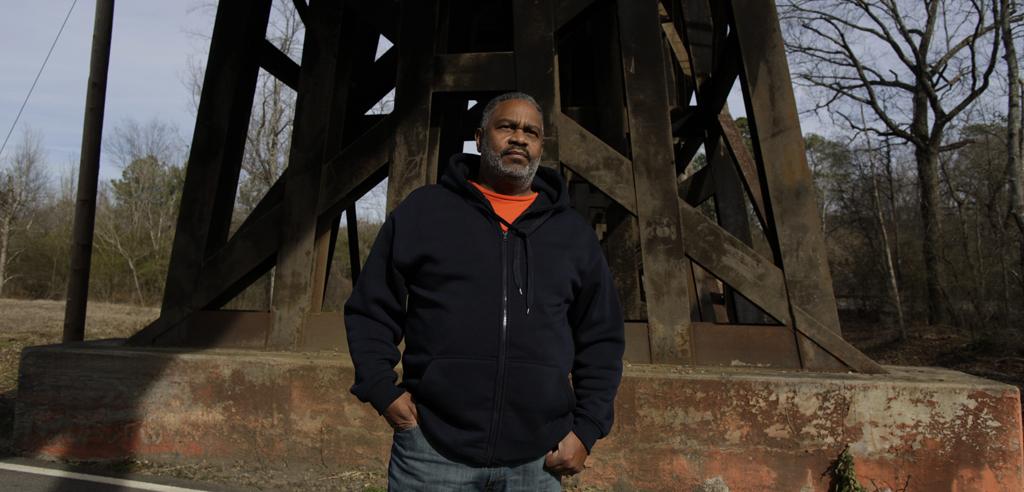

Anthony Ray Hinton, who served nearly 30 years on Alabama’s death row before he was exonerated and released in 2015, registered and voted in the 2016 election, too. Just weeks later, he received written notification from his local registrar that he was barred due to a felony conviction. “I felt heartbroken,” he recalled. “I felt that I had paid a debt I should never have had to pay in the first place, and to be told I couldn’t participate in an election was heartbreaking.”

With legal assistance, Hinton was able to straighten out the discrepancy after paying a fee. “Everybody doesn’t have the privilege that I had, to have a lawyer to go with me to fix this so I could vote. The process is confusing and intimidating and it’s a deterrent. To ask all the questions and make you talk about your conviction over and over, and charge a fee and make mistakes. It’s nerve wracking and most people just walk away. They try to make it hard.”

Danielle Lang wishes the State of Alabama would do more to maximize the impact of the new law clarifying moral turpitude by using its resources and influence to spread the word online and in the text of voter registration forms. “We are fighting an uphill battle because, for decades, the State of Alabama has been telling people with felony convictions that they can’t vote,” she said, “and it is doing nothing to counter that message now.”

In federal court earlier this year, the State argued that disenfranchisement policies impose only “a minor disability” and did not warrant the public education outreach that legal advocates were requesting. The judge ruled for the State, leaving advocates to try to fill what they see as a void in public education efforts.

“It would be easy to better educate people about their rights, but the State has instead been vigorously fighting to make no change,” said Lang. “I don’t see any reason for that other than voter suppression and an effort to keep people in the dark.”

* * *

As long as the Fourteenth Amendment is interpreted to inoculate felony disenfranchisement from constitutional challenge, reform efforts rely heavily on state-by-state strategies. “They can almost pass any law restricting our vote that they want, and if you want to change it, you have to do it through your legislature,” Bruce Reilly explained. “There is no constitutionally guaranteed right to vote for us.”

Recent years have seen a growing reform trend in many states, including Virginia and California. This fall, Florida voters will consider a ballot initiative that would end permanent felony disenfranchisement for many people with felony convictions in the state by automatically restoring voting rights after release from incarceration — except in cases of individuals convicted of murder or sex offenses. Passage of the measure would significantly transform one of the nation’s strictest and most infamous disenfranchisement schemes but still leave some classes of citizens barred from the ballot box.

Floridians for a Sensible Voting Rights Policy, Inc., a Tampa-based organization, maintains a website urging voters to reject the ballot initiative that would allow for automatic restoration of voting rights upon leaving jail or prison. Instead, they advocate “honoring the constitutional ban on felon voting while restoring the right to vote to convicted felons who complete their sentences only after a thorough, case by case review.” An accompanying blog features posts publicizing recidivism rates and highlighting inflammatory criminal cases as examples of people undeserving of restored rights.

Where reforms are won and implemented, the nation gets a glimpse into the consequences of disenfranchisement through the effects of its removal. In December 2017, Alabama held its first statewide election since defining moral turpitude. As private organizations, legal services offices, and activists like Dothan’s Reverend Kenneth Glasgow led efforts to register newly enfranchised voters, conservative outlet Breitbart News reported on the “Soros Army” registering “convicted felons to vote,” and Roy Moore himself tweeted warning that “thousands of felons” were being registered to swing the election. In the end, Democratic candidate Doug Jones defeated Moore, becoming the state’s first Democratic senator in a quarter century. Moore and his supporters may view that result as illegitimate, but others see it as an important move toward legitimacy.

“Any system that disenfranchises six million citizens is not a true democracy, period. And if you then factor in that a disproportionate amount of those disenfranchised citizens are part of a group that has been persistently marginalized, it’s an even greater stain on our democracy,” said Danielle Lang.

* * *

In fall 2016, Alabama Secretary of State John H. Merrill became somewhat infamous in voting rights circles for an interview denouncing automatic voter registration. In the video footage, tall and slim Merrill sits alongside an American flag and ivory fireplace. He recites a list of Black civil rights activists before explaining, “These people fought. Some of them were beaten. Some of them were killed, because of their desire to ensure that everybody that wanted to had the right to register to vote and participate in the process. I’m not going to cheapen the work that they did.”

“Just because you’ve turned 18 doesn’t give you the right to do anything,” he continued. “If you’re too sorry or lazy to get up off of your rear and go register to vote, or go register electronically, you don’t deserve that privilege. As long as I’m Secretary of State of Alabama, you’re gonna have to show some initiative to become a registered voter in this state.”

On Independence Day of 1852, in Rochester, New York, abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass delivered his famed address, “What To The Slave Is The Fourth of July?” One of the most haunting lines is at once a diagnosis and prediction for a nation then not yet one century old: “America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.” A prophecy our present seems to fulfill.

What mental gymnastics must it take to cite Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, and Rosa Parks as if anything about their legacies would be insulted by the implementation of broad and accessible voting systems? What falsehoods are required to believe a nation can, at once, be the world’s greatest democracy of justice and equality, boast the world’s highest incarceration rate, and bar from voting more than six million citizens? And what dissonance must we employ to accept and celebrate the Fourteenth Amendment as a legal foundation for all three?

Increasingly, critiques of felony disenfranchisement reference the racial motivations of those who crafted 19th century laws linking voting rights to criminal convictions. But there is more there. The racial history of felony disenfranchisement is indeed relevant to its present, in part because of the continued burden disproportionately borne by Black Americans and other people of color – and more so, perhaps, because descendants of Africans enslaved in America have long been the most intimately reviled American child, suffering as the perpetual illustration of a lesson the nation refuses to learn.

“Last night, Black voters in Alabama did not vote to save the state or the nation,” Dr. Theodore R. Johnson, a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, tweeted following Senator Doug Jones’s election. “They simply voted for self-preservation. Any ‘saving’ that occurred happened by proxy. But this is the story of Black America – the Union becomes more perfect when Black folks aren’t disenfranchised.”

* * *

In 2002, the New York Times interviewed Southern leaders reflecting on their civil rights era records with hindsight and regret. “Today there is wide consensus that racial segregation is reprehensible and immoral,” the article read. “But 40 years ago, that wasn’t so clear.”

Wasn’t clear to … whom? To the Black Americans and others who risked violence and death to protest segregation, discrimination, racial violence, and systematic injustice? When segregationists, or lynch mobs, or slave owners are excused as products of their time, are we to think of the segregated, the lynched, and the enslaved as “ahead of their time?” Was their knowledge of the injustice they faced some type of supernatural premonition? Or awareness of a truth American political institutions had been designed to ignore?

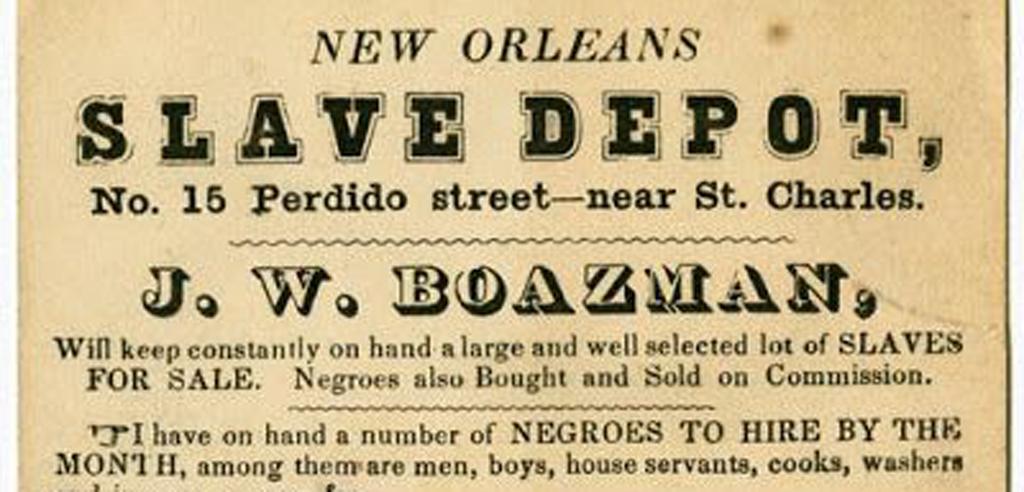

If the enslaved could vote, it would not have taken a civil war to end slavery. The statement is so obvious it seems ridiculous: of course a system could not respect people enough to allow them to vote, and also disrespect them enough to treat them as property to be bought, sold, and abused. But there is more there. If disenfranchisement is a tool of oppression, can enfranchisement be a protection against oppression, that benefits the voter and the system their votes help shape?

Congress would not have needed to pass the Voting Rights Act, Civil Rights Act, and other civil rights legislation; the United States Supreme Court would not have needed to strike down interracial marriage bans and segregation in schools, buses, and parks; and Jim Crow would not have lasted as long as it did if Black people in the South had been able to vote – and that is why they were kept from the ballot box by law and violent intimidation for generations.

Times do change, but not in ways mysterious or unpredictable. If blatant forms of inhumane oppression were seen differently “back then,” it is because disenfranchisement distorts and blinds a nation’s collective view. The ideals of human rights and justice are destroyed and corrupted when whole segments of the population, already disproportionately suffering the effects of inequality, oppression, and exploitation, are also barred from wielding a ballot.

This is “the story of Black America,” to use Dr. Johnson’s phrase, because this has been the position, the plight, and the struggle of Black America. Disenfranchisement maintains an unjust status quo by politically marginalizing the very communities best positioned to testify to the effects of injustice. We should regard disenfranchisement with suspicion and intolerance – not just because Black communities remain heavily burdened, but because centuries of Black lives demonstrate the policies’ heavy toll. Honest engagement with that long history can open our eyes to the consequences of labeling whole communities not quite equal enough to speak.

“The people most impacted by a system are in the best position to think about ways to fix a broken system,” said Ryan Haygood of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, which recently launched a campaign to end felony disenfranchisement in the state. “If you create a system where people with convictions can’t vote to impact policies, you are weakening their voice and the voices of their communities and also undermining the legitimacy of the political and criminal justice systems.”

A denunciation of disenfranchisement is not an ode to democracy. Voting alone will not save us. But the dissonance of idealizing freedom and democracy while maintaining an electoral caste system and the world’s highest incarceration rate will leave us little worth saving.

If in 50 years, the evil of mass incarceration is portrayed as an unknowable injustice – this era’s particular version of a “different time” – our perpetuation of the unjust legacy of disenfranchisement will stand as damning evidence. Our unironic praise of the Fourteenth Amendment, with its criminal exception to voting rights intact, will be our telltale heart. And our layer of history will leave this lesson again unlearned.

Blind spots do not excuse when they are willful. The rest of the story is there if we care to know it.

It always has been.

* * *

In 1828 and 1831, a young man named Abraham Lincoln traveled down the Mississippi River from his home in Indiana to the bustling port city of New Orleans, Louisiana. These trips, the only visits to the Deep South Lincoln would make in his life, helped to form the man who would later be president and lead the nation through civil war.

Twenty years after Congress banned the importation of enslaved Africans from abroad, settlers moving to newly opened territories in Alabama and Mississippi relied on the domestic slave trade to accumulate human property. New Orleans, one of the region’s busiest markets, was home to more than 46,000 people by 1830; over 7500, or about one in six, were enslaved. According to a 1901 biography, in New Orleans in 1831, Lincoln witnessed an auction of enslaved people that left him deeply troubled. Perhaps he encountered the slave market at 216 Baronne Street – just three minutes walk from where the Roosevelt Hotel stands today, and where, in 1866, the New Orleans massacre raged.

Lincoln lived 34 years past 1831. He oversaw the legal abolition of American slavery, employed emancipation as military strategy, proclaimed preserving the Union his one true goal, and endures as one of the nation’s most debated and storied 19th century presidents. He was, at once, product and producer of the time in which he lived – but for at least one moment, before he was any of those things, he was a man who recognized in Black suffering a timeless lesson.

“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master,” Lincoln wrote in a personal journal while living in Springfield, Illinois, in 1858. “This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is not democracy.”

A reflection befitting its era. And ours.

Makaiya Bullitt-Rigsbee provided research assistance for this report.