Ohio had barely entered statehood in 1803 when thousands of Black Americans began arriving there from the South. Many were escaping to this “free” state from enslavers in Virginia and Kentucky, just across the Ohio River. Some people even swam across the mile-wide river, or walked across its ice in winter, believing that freedom and opportunity awaited them on the other side. Abolitionism had many supporters in Ohio. Cincinnati, along the river, had a growing Black community. Ohio’s Black population quintupled between 1800 and 1810, from a little over 300 people to nearly 1,900.

But most of the white men who wrote the state’s 1802 constitution and its earliest laws came from Virginia and other “slave” states. Many had been enslavers before moving to the Ohio Territory, where slavery was outlawed. The document they drafted did not change that, but it took away a right Black men had had in the Ohio Territory before statehood—the right to vote. And that was only the beginning.

To stop Black people from moving to the state, the all-white state legislature approved “An Act to Regulate Black and Mulatto Persons” in 1804, and amended it three years later, stripping Black residents of their rights in the courts. Starting April 1, 1807, Black people in Ohio were barred from testifying in any case, civil or criminal, in which one of the parties was white. Ohio’s “Black Laws,” as the measures became known, gave white supremacy priority over justice.

A System of Targeted Laws

Ohio’s discriminatory laws restricted all aspects of daily life for Black residents in the state.

Black residents had to register with the county clerk within two years of arriving in Ohio, pay a fee of 12 1/2 cents, and obtain a court order attesting to their being free. They had to be able to produce this proof of freedom at any time.

White employers who hired unregistered Black workers faced fines of $50 per employee.

If the employee turned out to be a fugitive from slavery, the employer was fined 50 cents for each day of employment—paid to the enslaver. Anyone who harbored alleged “fugitives” or hindered their capture could be fined from $10 to $50.

Ohio’s new system of tax-supported “common” schools—public schools—was for white children only. That part of the law would be reinterpreted several times over the next few decades but never allowed Black children to attend tax-supported schools with white children.

Though Ohio was a “free” state, the law all but made its courts, constables, and sheriffs tools of Southern enslavers. Enslavers or their agents needed little evidence to get Ohio judges or local justices of the peace to order people who were alleged to have escaped from slavery arrested. The law required sheriffs and constables to execute those orders—and enslavers paid them for their efforts.

The law offered Ohioans a cash incentive to inform on their neighbors by alerting local authorities whenever a white employer hired Black workers who had not registered or did not have proof of freedom. Half the fines imposed on employers for each such hiring would be paid to the “informer.”

The 1807 amendments not only closed the courts to Black Ohioans—they made it harder than ever for

Black people to scrape together a living. The fines on white employers for hiring unregistered Black workers were tripled to $150—or about $4,000 today—per employee. (That meant more money for informers, too.) Many employers minimized the risk by refusing to hire Black workers altogether.

The amendments also required newly arriving Black citizens to persuade two white Ohio landowners to put up a $500 “good behavior” bond, agreeing to pay authorities that amount if the Black person got in legal trouble. Abolitionists pointed out that few white Ohioans could afford that—$500 in 1807 would be worth more than $13,000 today. And the law set the bar impossibly high: a Black person needed to recruit those well-off white sponsors within 20 days of arriving in Ohio.

The testimony law barring Black people from testifying against white people meant white criminals could, and did, rob and assault Black people with impunity. It meant unscrupulous white merchants could, and did, defraud Black customers with no fear of being successfully sued for their frauds. Black residents who got swindled out of land could not turn to the courts.

Codifying Racism

The harsher requirements added to the “Black Laws” in 1807 may have been prompted in part by a Virginia law, enacted in 1806, that gave newly emancipated people 12 months to leave that state or else be re-enslaved.

But one thing was certain: the “Black Laws” codified white supremacy in Ohio. So did laws and court rulings that followed—barring Black men from the militia, barring Black adults from juries, barring Black children from learning alongside white children in public schools, and barring racial intermarriage.

Cases in which Black people were scammed, robbed, or even killed evaporated in court because of the testimony law. The Ohio Anti-Slavery Society’s 1835 report told of a Black family whose home had been broken into and looted the year before. The evidence was clear—one perpetrator even confessed—but defense lawyers said the law invalidated the family’s sworn claims to the stolen items, “and the robbers were cleared.” Another judge barred testimony from eight Black men who had witnessed a white man “murdering a colored man…[and] the murderer escaped unpunished.”

Excluded from steady jobs, many Black Ohioans resorted to piece work, which in turn made them vulnerable to more crimes; profiteering kidnappers snatched free Black people off Northern streets and sold them to Southern enslavers. The New York Colored American reported that some offers of short-term work for Black men—moving livestock to or from Kentucky, for example—were ruses that ended with kidnappings.

In 1840, Charles Scott and his brother, free Black men living near Cincinnati, found short-term work driving cattle across the Ohio River—but on the Kentucky side, the white men who had hired them “clapped them in jail, as runaway slaves,” The Liberator reported. Jailed for six weeks before he could prove his freedom, Charles Scott sued the white men for false imprisonment. They demanded he withdraw his suit. When he refused, they came to his cabin on a Saturday night.

Mr. Scott, his wife, and a friend—a light-skinned, mixed-race woman—were singing by the fireplace when the white men arrived. Mr. Scott was “shot dead by his own hearth-stone, while singing to his wife,” The Liberator said. His killers were arrested, but the “Black Laws” barred his widow from testifying against them.

A white judge interpreted the law broadly—perhaps giving priority to justice, not white supremacy. He allowed the Scotts’ light-skinned friend to testify, reasoning that she was more white than Black. The killers were convicted. The Colored American’s editors said the result, if not the reasoning, foretold a day when “the Black Laws will soon give way to make room for just ones.”

In page after page, the Ohio anti-slavery group’s report described how mechanics, carpenters, and other skilled Black tradespeople were denied jobs because of the “Black Laws” and the racist attitudes of many white employers and workers. “This combined oppression of public sentiment and law reduced the colored people to extreme misery,” the report said.

John Malvin, a free Black carpenter who came to the state from Virginia in 1827, later wrote: “I thought upon coming to a free state like Ohio, that I would find every door thrown open to receive me, but from the treatment I received by the people generally, I found it little better than in Virginia…I found every door closed against the colored man in a free state, excepting the jails and penitentiaries.”

Like many other Black citizens, Mr. Malvin was not just trying to make a living. He was also trying to buy freedom for a loved one—his father-in-law, enslaved in Kentucky. The antislavery group’s reports told of Black families in similar straits, such as a girl about 10 years old, working to help purchase her father’s freedom, and a husband who’d negotiated a price of $420 for his enslaved wife, saved up that amount, and headed south to buy her freedom only to learn that her enslaver had raised the price to $450 because she was “in a family way.”

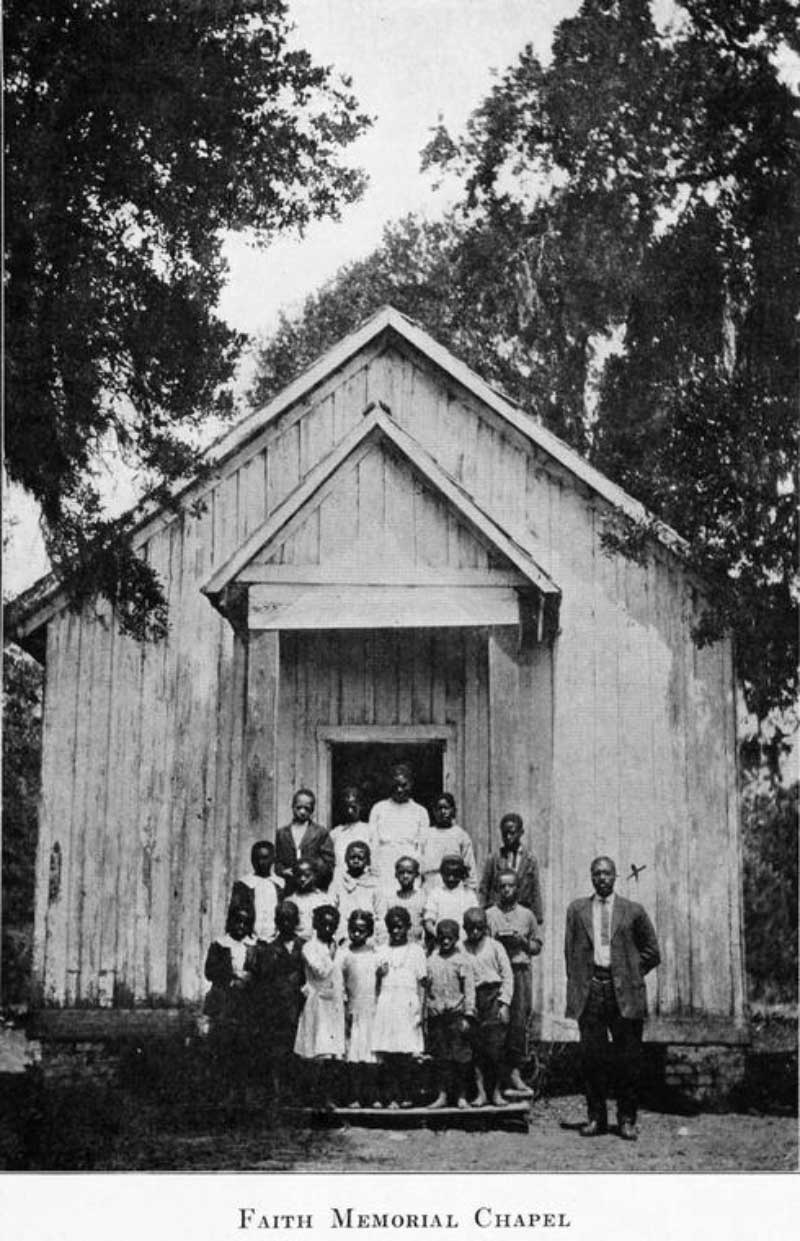

Since Ohio’s public schools were only open to white children, abolitionists started their own schools for Black children—and periodically faced attacks by white citizens. A “vigilance committee” in one town threatened to tar and feather a white Oberlin College senior “and ride her on a rail” if she kept teaching the town’s Black children.

Historians note that in some years, the bond and registration requirements of the “Black Laws” went largely unenforced. In other years they were applied with a vengeance—to entire Black communities.

Enforcement and Violence in Cincinnati

By 1829 Cincinnati’s Black community had grown to about 2,200 people, almost 10% of the city. Black and Irish workers competed for jobs on the docks. On June 30, the city announced it would enforce the “Black Laws” en masse. Within 30 days, registrations would be required, proofs of freedom demanded, and Black residents lacking two white sponsors willing to post the $500 bond would be banished.

Black Cincinnatians persuaded the city to grant them 30 extra days. They dispatched representatives to Canada to ask if they could relocate there. Canadian officials said yes.

But white Cincinnati men were already forming mobs. For several days in August 1829, they terrorized Black neighborhoods, pillaging some homes and torching others. Some residents were beaten, and hundreds fled. Nearly half of Cincinnati’s Black residents eventually resettled in Canada.

Mass Displacement of Black Residents

On January 21, 1831, an announcement appeared in the Portsmouth, Ohio, Courier: “The citizens of Portsmouth are adopting measures to free the town of its colored population.”

A hundred white residents of the southern Ohio town had signed a petition vowing to expel Black neighbors who had not registered and secured the $500 bond. African Americans called that January day “Black Friday.”

Eighty Black residents of Portsmouth packed their belongings and headed north, hoping to resettle in a less hostile part of Ohio.

A year later, when a bill to modify the testimony law (by allowing testimony from a Black man if a white man vouched for him) faced votes in the legislature, a Dayton newspaper asked readers:

“Are you ready for this state of things? We appeal to the laboring portion of our fellow countrymen. Are you ready to be placed on a level with the ‘n____s’ in the political rights for which your fathers contended? Are you ready to share with them your hearth and your house? Are you ready to compete with them in your daily vocations?”

The bill failed on a close vote.

In 1846, after a wealthy white Virginian bequeathed freedom to 383 Black people he had enslaved, the executor of his will prepared to resettle the formerly enslaved people on farmland purchased in Mercer County, Ohio, near the Indiana line. But local white farmers, many of them recently arrived from Germany, issued a warning: “Resolved, that we will not live among negroes, as we have settled here first…that we will resist the settlement of blacks and mulattoes in this county to the full extent of our means, the bayonet not excepted.”

The freedpeople were forced out of Mercer County.

Other States’ “Black Laws”

Southern legislatures imposed barbaric laws on Black residents, whether enslaved or free, for centuries. Ohio was among the first Northern “free” states to legislate white supremacy, but it was not the last.

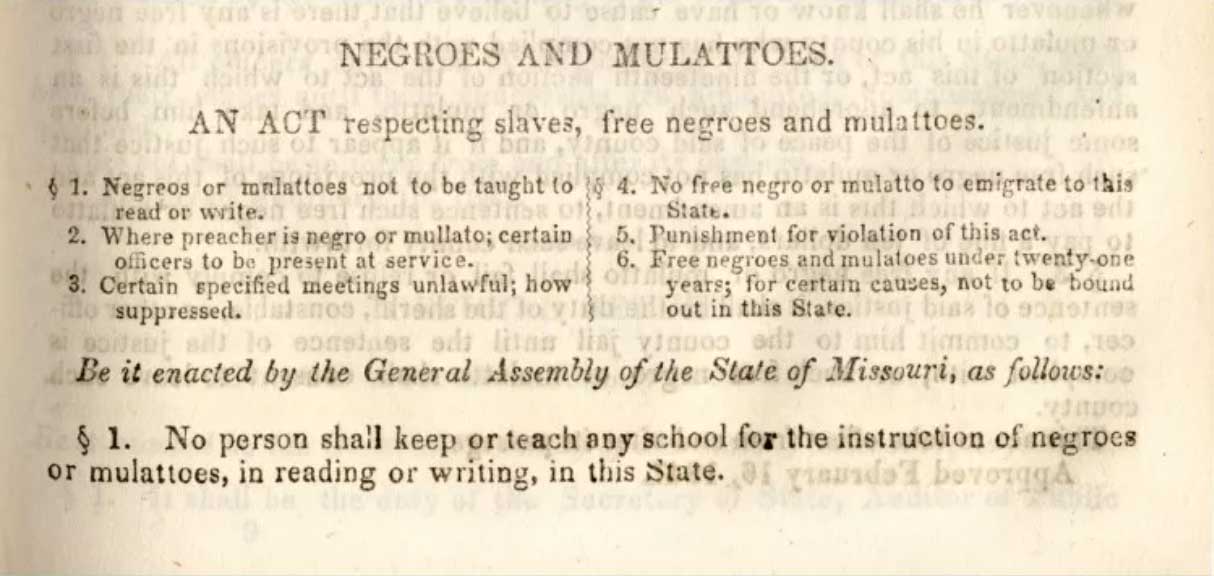

In 1847, Missouri passed a law that prohibited Black people from learning to read or write. (Missouri State Archives)

In 1843, Indiana barred Black children from public schools. Eight years later it closed its doors to African Americans wanting to settle in the state and fined anyone who helped or hired them. In 1847 Missouri outlawed schools that offered “the instruction of negroes or mulattoes, in reading or writing.” California’s 1850 law prohibited Black testimony in white defendants’ criminal cases. Illinois required $1,000 bonds from new Black citizens, barred Black witnesses’ testimony against white people, and prohibited Black people from meeting in groups of three or more.

Faith Memorial Chapel in Ohio, a church and school established after the Civil War for African American children denied public school educations. (New York Public Library)

Repeal and Resistance

Ohio’s “Black Laws” were officially repealed in 1849—or “modified,” as one historian put it. Black citizens could now testify, regardless of litigants’ race. They no longer needed the $500 bond. Their children could attend public school—albeit in separate schoolhouses, away from white children. Black Ohioans still could not be jurors, join the militia, receive public relief if they were in need, or vote.

If the main goal was to drive African Americans away, the laws failed. The nearly 1,900 Black Ohioans in 1810 more than doubled by 1820. The 1860 Census counted nearly 37,000 Black residents. And some of the laws’ victims found ways to fight back.

The 80 Black residents driven out of Portsmouth started their own Ohio town—and made it a station on the Underground Railroad. Their counterparts who had been turned away from Mercer County, too, formed communities elsewhere in Ohio. Mr. Malvin, the carpenter who’d found no Ohio doors open to him, helped start schools for Black children and, in 1865, was a delegate to a convention in Cleveland for a new national group launched by Frederick Douglass and other Black leaders. It was called the Equal Rights League.