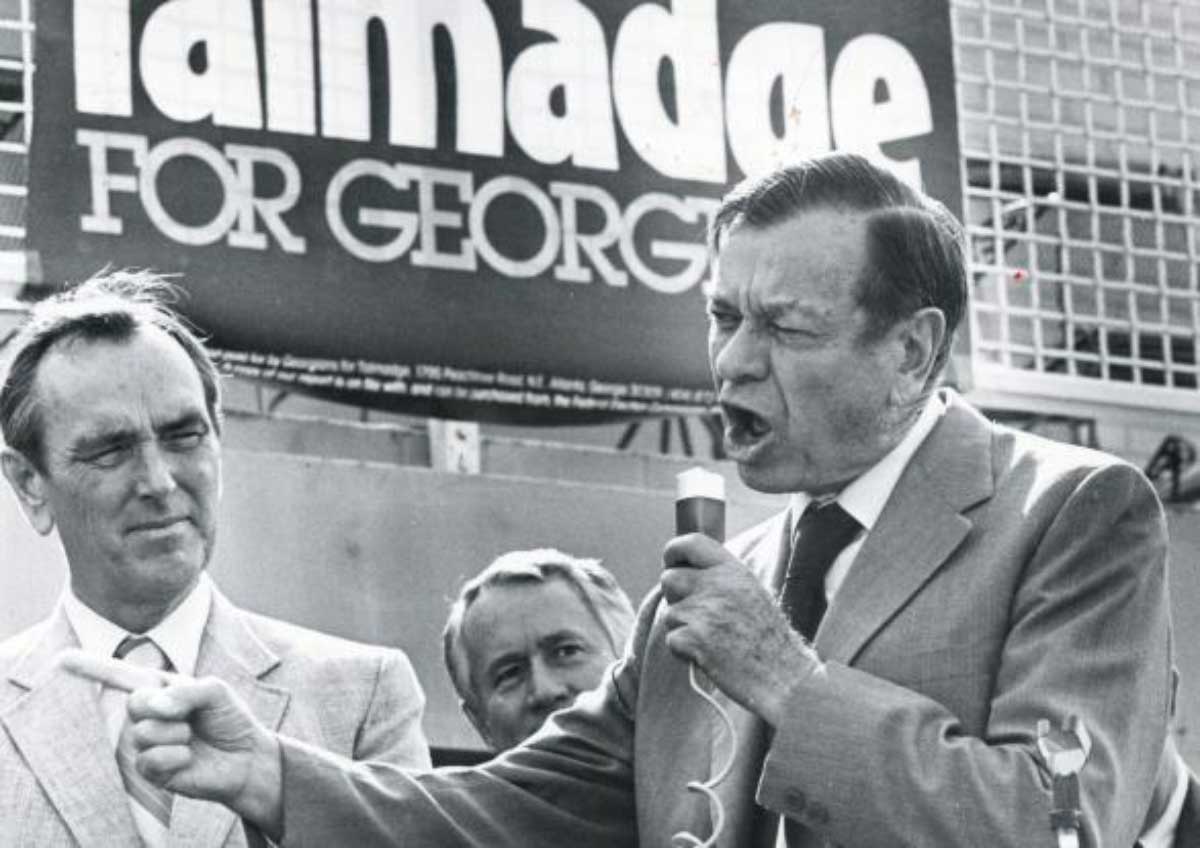

Georgia Gov. Herman E. Talmadge liked to portray himself as a champion of education who had built hundreds of new schools, many of them for Black children. When it came to integration, however, Mr. Talmadge said he would sooner end public education in Georgia than allow Black children to attend school with white children.

“There is only one solution in the event segregation is banned by the Supreme Court,” Mr. Talmadge declared on December 18, 1952, anticipating how the justices would rule in the case of Brown v. Board of Education. “And that is abolition of the public school system.”

Mr. Talmadge was not an outlier. “The mixing of races in the schools will mark the beginning of the end of civilization as we know it,” South Carolina Gov. James F. Byrnes, a New Deal Democrat and former U.S. secretary of state, told a group of white teachers in 1954. Defending that civilization fell to Southerners, he said.

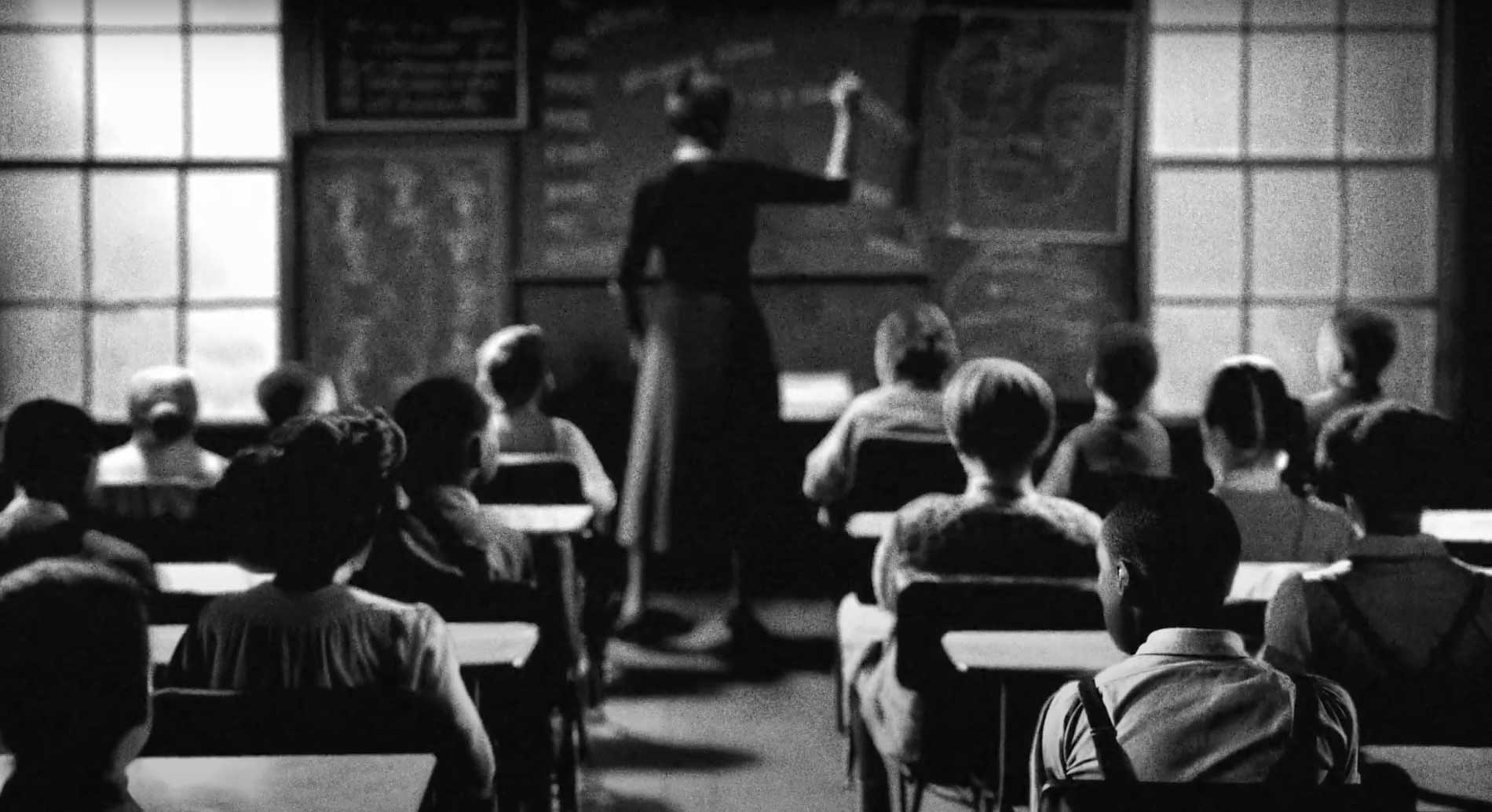

The cornerstone of that “civilization” was the South’s rigid racial caste system, enabled and enforced by the state-mandated segregation that had relegated generations of Black children to vastly underfunded, ill-equipped schools—and in some places even denied those children access to high school.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court invalidated racial segregation in public schools, ruling unanimously in Brown that separate education for white and Black children was “inherently unequal” and unconstitutional. Widely viewed as the beginning of the dismantling of the Jim Crow system, Brown galvanized civil rights leaders and enraged segregationist Southerners.

Launching Massive Resistance

A year later, in a decision known as Brown II, the Supreme Court opted for a gradualist approach, ruling that school integration should “proceed with all deliberate speed.”

The vagueness of the order, however, emboldened segregationists across the South. NAACP attorneys were forced to file hundreds of lawsuits over the next two decades in response to widespread efforts to evade the Supreme Court’s decision.

Even before Brown II was announced, voters in Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi had approved constitutional amendments authorizing their legislatures to abolish public education if they were ordered to integrate.

Opposition to school integration began coalescing into a mass movement of resistance, stretching from the Deep South to Virginia. While its best-remembered images are of white mobs shouting racial slurs at Black schoolchildren in Little Rock, Arkansas, and Birmingham, Alabama, the resistance was powered by a broad swath of segregationists whose tactics included legal maneuvering, school closures, intimidation, and economic reprisals as well as violence. The resistors were bankers and business leaders, Kiwanis and Rotary Club members and clergy, and middle-class members of White Citizens’ Councils who took pains to distance themselves from the Ku Klux Klan—as well as officeholders from local school boards to state capitols to the halls of Congress.

Teenage boys wave Confederate flags during a protest against school integration in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1963. (Flip Schulke/CORBIS/ Getty Images)

“If we can organize the Southern States for massive resistance to this order,” Virginia’s influential, long-serving senator, Harry Byrd, said in February 1956, “I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.”

Massive resistance was endorsed in most Southern editorial pages. In Virginia, one especially influential editor, James J. Kilpatrick of the Richmond News Leader, worked behind the scenes against desegregation with Mr. Byrd and state officials. Mr. Kilpatrick churned out editorials denouncing the Court’s ruling as “an act of usurpation” by “a judicial junta” and arguing that the 19th century doctrine of interposition allowed states to “interpose” themselves between the federal government and their citizenry. Virginia and a number of other states adopted this legal strategy to resist Brown and preserve segregation.

Mr. Kilpatrick would reveal his racial views several years later in an unpublished 1963 article titled “The Hell He Is Equal,” writing that Black people were “an inferior race.”

The Southern Manifesto

The call for resistance was enshrined in “The Declaration of Constitutional Rights,” also known as the “Southern Manifesto.” This document was crafted by Mr. Byrd and other Senators including South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond, Mississippi’s James Eastland, and Arkansas’s J. William Fulbright. Designed to win over moderates and Northerners, the manifesto was cloaked in a reading of the Constitution that invoked Civil War-era theories of states’ rights. Ignoring decades of racial violence, disenfranchisement, and lynching, it said the Court’s ruling was “destroying the amicable relations which have existed between the white and Negro races.”

Harry Byrd of Virginia, who convinced 101 of the 128 congressmen representing the 11 states of the old Confederacy to sign “The Southern Manifesto on Integration.” (Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

Expanding on the interposition argument, the Manifesto urged states to resist Brown. It was signed by 19 senators and 82 representatives, all from former Confederate states.

The support of prominent national figures further emboldened those who fought desegregation on the local level. Amis Guthridge, an attorney and prominent Little Rock segregationist, made note of the Manifesto at a rally in Jacksonville, Arkansas, telling the crowd, “We are not going to have trouble with public office holders.” Mr. Guthridge took that message across the South in speeches that claimed school integration was a Soviet scheme “to mongrelize the white race in America.”

Herman Talmadge had used similar language in his 1955 book You and Segregation, warning that nations “composed of a mongrel race” were easy prey—precisely “what the Communists want to happen to the United States.” The message resonated amid the climate of the Cold War. One year later, voters sent the former governor to the Senate.

Southern legislatures passed more than 450 measures designed to limit, delay, or evade Brown. The laws denied funding to schools that integrated, enabled firing of school employees who supported desegregation, suspended compulsory attendance in desegregating schools, authorized use of public funds to open hundreds of private white academies, and provided tuition grants to white families that encouraged them to pull their children out of public schools.

Herman Talmadge (right) during his 1980 Senate reelection campaign.

In 1955, North Carolina pioneered another tactic: the pupil placement law. Making no mention of race, the law empowered districts to maintain nearly all-white schools by assigning students to schools based on “race-neutral” criteria such as intelligence and psychological readiness. By 1958, every Southern state had a version of the statute.

Lest political pressure, public agitation, novel legislation, and revamped policies fail to stop desegregation, white violence emerged as yet another tactic deployed to nullify the force of Brown. Two Tennessee public schools were bombed in 1956. Four years later a bomb destroyed an Atlanta school, prompting The Atlanta Journal-Constitution editor Ralph McGill to write: “Men and women in high places who organize groups to resist court orders, those who urge pledges of never surrendering, and who encourage those of the Klan mentality, did not toss the explosive at the school. But in a very real sense, their hands were there just the same.”

Even President Dwight D. Eisenhower took no public stance on the merits of Brown but in private he sympathized with white Southerners. At a White House dinner while the case was pending in the Supreme Court, Mr. Eisenhower sat Chief Justice Earl Warren near John W. Davis, the Southern lawyer who had argued for segregation in Brown. The president called Mr. Davis “a great man,” and told the chief justice that Southerners weren’t “bad people…All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big, overgrown Negroes.”

“Our Way of Life”

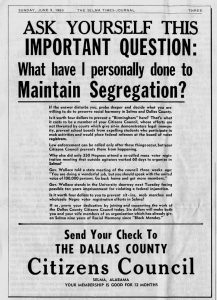

A White Citizens’ Council recruiting pamphlet published in the Selma Times-Journal on June 9, 1963.

Amid this atmosphere in the South, there was no room for moderates. The White Citizens’ Councils, whose numbers reached 250,000 by 1958, saw to it that Brown’s supporters lost jobs, mortgages, credit, and social standing. NAACP activists were labeled “Communist outside agitators.” In South Carolina, where 55 Council chapters were active by July 1956, dozens of Black people were fired or evicted from their farms after the signing of a pro-integration petition in Orangeburg and Clarendon counties.

In Walthall County, Mississippi, after the NAACP submitted a school desegregation petition, officials closed the county’s Black schools for two weeks and fired school employees believed to have aided the desegregation drive. When 53 Black residents of Yazoo County, Mississippi, signed a desegregation petition, the Citizens’ Council published their names in a newspaper ad. Retaliation was swift. Petitioners lost their jobs. A local bank’s president telephoned his customers on the list and told them to “get their money out, that the bank did not want to do business with them any longer.”

Meanwhile, Georgia’s Board of Education barred textbooks from describing discrimination against Black people. “There is no place in Georgia schools at any time for anything that disagrees with our way of life,” the chairman explained.

Showdown at Little Rock

Similar assumptions guided events even in places where desegregation appeared to be working. On September 4, 1957, shy, studious Elizabeth Eckford, 15 years old, was the first of nine Black students to arrive at all-white Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas, on the first day of school. Elizabeth’s family had no telephone. She had not been informed that a group of ministers planned to escort the nine to school.

White protestors surround Elizabeth Eckford as she integrates Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. (Will Counts/AP Photo)

Little Rock officials had agreed on a plan to gradually integrate schools, starting with Central High. Seeing helmeted guardsmen with rifles in front of the school that morning, Elizabeth assumed they were there to protect her. But Gov. Orval Faubus had sent them—not to prevent violence, as he claimed, but to block the nine students from attending school with Central’s 2,000 white students. As Elizabeth approached the entrance, guardsmen crossed their rifles in front of her. They directed her back into the street, toward a white mob shouting racial slurs. “Lynch her!” people yelled. Elizabeth looked imploringly at one gray-haired woman whose expression seemed kind. The woman spat in her face.

At a time when one in four white Southerners told pollsters they “favored violence, if necessary, to prevent school desegregation,” Gov. Faubus was overwhelmingly reelected the following year.

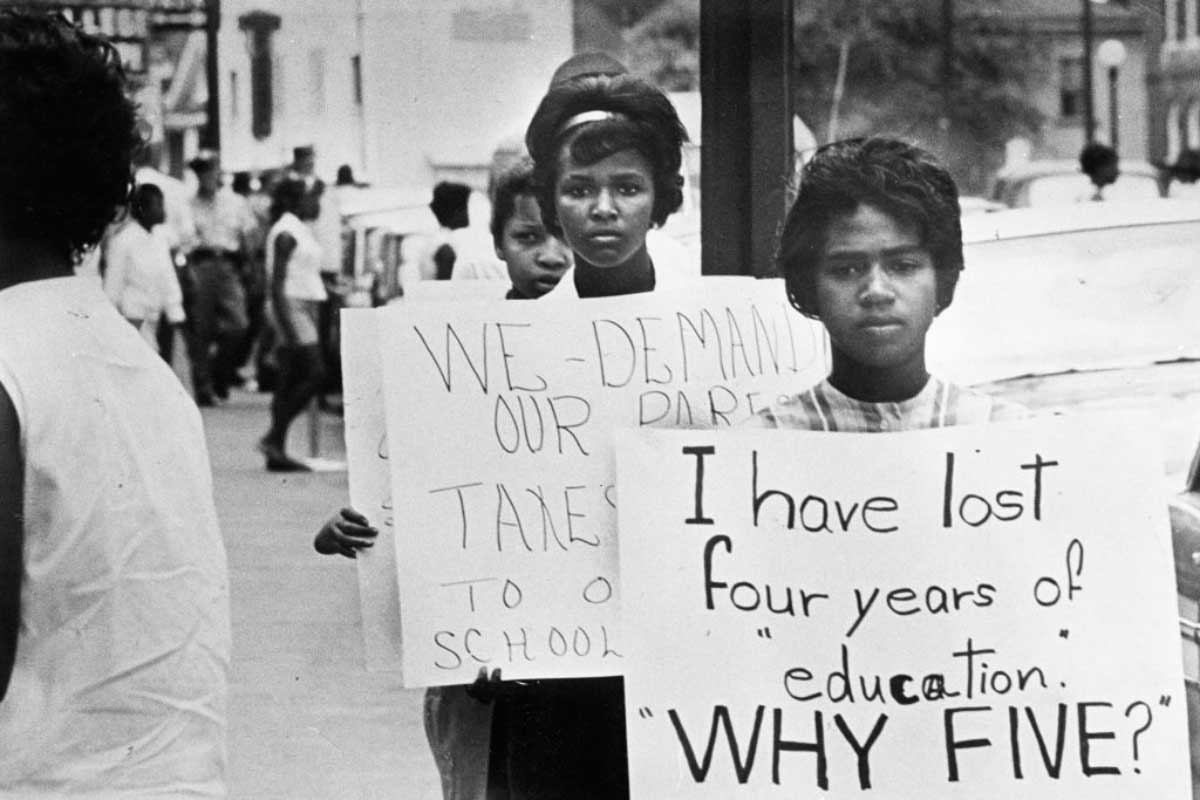

As resistance to desegregation continued, Black children still attended underfunded schools or—when officials closed schools for weeks, months, even years—stayed home. In 1956, Virginia’s governor closed three cities’ schools rather than integrate. The Supreme Court ordered them reopened. In 1959, Prince Edward County, Virginia, closed its public schools for five years, diverting tax monies to build a K-12 private academy for 1,400 white students and allotting their families tuition grants. Some 1,700 Black students were denied public education in the county where their parents worked and paid taxes.

Teenage girls hold signs protesting the closure of public schools in Farmville, Virginia, in 1963. (Hank Walker/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

By the time the Supreme Court reopened those schools in 1964, the county’s 3% illiteracy rate for Black residents ages 5 to 22 had risen to 22%.

Black families who tried to integrate Alabama schools in 1963 faced death threats, white mobs, and school doors blocked by armed police despite federal judges’ integration orders. “We are not fighting against the Negro people,” Gov. George C. Wallace said in a Labor Day speech. “We are fighting for local government and states’ rights.”

A few days later, Sonnie Hereford III, a Black physician and civil rights activist in Huntsville, walked his son to Fifth Avenue Elementary to start first grade. “There was a mob out there, I guess 150, 175 parents and kids,” Dr. Hereford remembered a half-century later. “They called my son and me everything you can think of.” State troopers turned the father and son away, saying Gov. Wallace had closed the school. Similar scenes played out across the state—until President John F. Kennedy federalized Alabama’s National Guard and reopened schools.

Thus did six-year-old Sonnie Hereford IV become the first Black child to integrate an Alabama public school—nine years after Brown.

Dr. Sonnie Hereford III accompanies his six-year-old son, Sonnie Hereford IV, to school on September 9, 1963. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

In fact, a decade after Brown, 99% of Black children in America still attended segregated schools. When federal judges approved token integration plans, and white parents availed themselves of pupil placement laws, “freedom of choice,” and private academies, or moved to the suburbs, little in the racial landscape of education changed.

In 1966, 450 Black students enrolled in Grenada, Mississippi, public schools under a court-ordered integration plan. After parents were threatened with firings and evictions, 200 pupils withdrew.

Civil rights activist Bruce Hartford described what the schoolchildren endured the first morning of classes: “A huge white mob surrounds Grenada’s elementary and high school…Radio-equipped scouts in pickup trucks for Negro students coming to school and direct the mob to attack them.” Police did not intervene.

The New York Times reported how that day ended: “A throng of angry whites wielding axe handles, pipes and chains” attacked Black students leaving school. One pupil, age 12, “ran a gantlet of cursing whites for a full block, his face bleeding, his clothes torn…He finally escaped, limping.”

The Children of Brown

Integration gained momentum after the 1964 Civil Rights Act—which empowered federal officials to enforce desegregation—and other steps by the courts and Congress. By the early 1970s, schools in the South were the nation’s most integrated. Academic achievement increased. The children of Brown went to college and, over time, made substantial gains in income, employment, and health.

Starting in the 1990s, however, the Supreme Court ended hundreds of school desegregation orders and plans across the country. Today, 67 years after Brown, racial and economic segregation are rising sharply among schoolchildren in the South and across the country. The number of “apartheid schools,” where white enrollment is one percent or less, has increased. Growing disparities in funding and other resources are recreating separate and unequal schools for children of color and, according to a 2019 report, “placing the promise of Brown at grave risk.”