Community members gathered in Salina, Kansas, on June 18 to dedicate a new historical marker in memory of Dana Adams, a 19-year-old Black man who was lynched by a white mob near the Union Pacific railroad depot in Saline County on April 20, 1893.

Sponsored by members of the Dana Adams Project 1893 in partnership with EJI, the marker was placed between the local library and the courthouse at the Robert Caldwell Plaza. Located at 301 West Elm Street in Salina, the plaza is named after Salina’s first Black mayor.

Over a hundred community members attended the dedication ceremony, including Salina’s mayor Trent Jones, Sheryl Wilson of the Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, representatives of local institutions and faith communities, and members of the Dana Adams Project 1893.

An official proclamation detailing Mr. Adams’s lynching and calling the community to remembrance was read in commemoration of the ceremony’s efforts towards restorative truth-telling.

The Lynching of Dana Adams

On April 20, 1893, a mob of at least 50 white railroad workers lynched 19-year-old Dana Adams in Saline County near the Union Pacific depot. That morning, Mr. Adams and three other Black men were in the waiting room of the train station when a white worker ordered them to leave without justification, leading to an altercation. Police arrested Mr. Adams after the white man accused him of attempted murder.

Accusations lodged against Black people were rarely subjected to serious scrutiny during this era. The mere mention of Black-on-white violence regularly led to criminalization and racial terror violence.

Within hours of his arrest, Mr. Adams was put on trial and, without a lawyer to defend him, he was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison.

Ignoring rumors about plans to lynch Mr. Adams, the police put Mr. Adams on a train headed out of town, but the lynch mob disconnected the train car holding Mr. Adams and abducted him. Police officers allowed the mob to drag him off the train, handcuffed and pleading for his life, and hang him from a telegraph pole at the Union Pacific depot. Several white men stripped the clothes from his body to take as souvenirs.

Although more than 200 spectators attended the lynching, no one was held accountable for lynching Dana Adams.

Racial terror violence was intended to instill fear in the entire Black community, and it was dangerous for Black people to seek accountability after a lynching. Dana Adams’s father nonetheless sued the City of Salina for damages after his son was lynched. The city refused to acknowledge the harm done to the Adams family; it offered only $2 in damages and would not identify or prosecute those responsible for the lynching.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of EJI’s campaign to recognize the victims of lynching and advance honest conversation about the legacy of racial terror by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and inviting community members to visit the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, where the horrors of these racial injustices are acknowledged.

Through the Community Remembrance Project, EJI has joined with dozens of communities to install historical markers where the history of lynching is documented in our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face, from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, and police violence to the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that continues to burden people of color today.

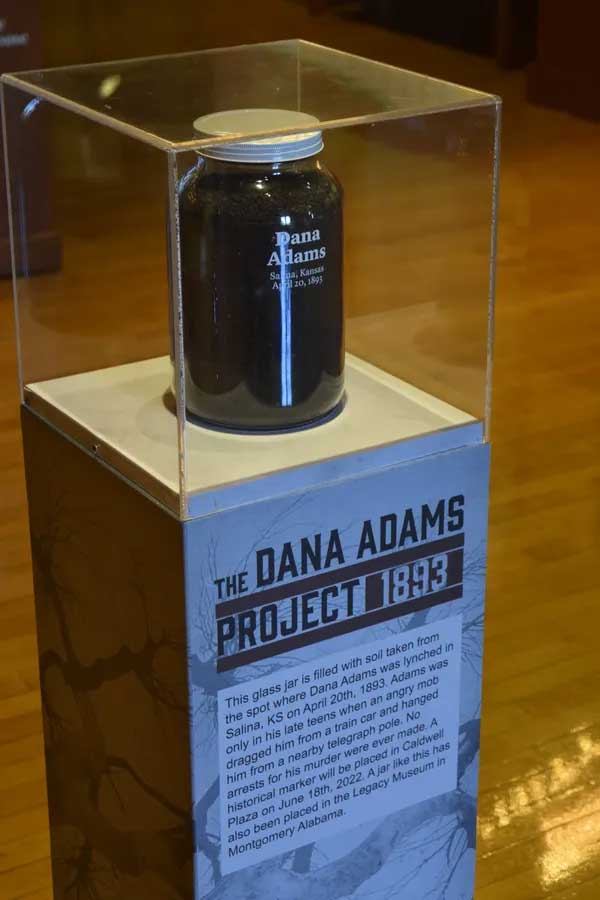

In response to EJI’s call for community remembrance, Saline County community members came together in 2020 to form a coalition in pursuit of memorializing Dana Adams. In October 2021, the coalition hosted a community soil collection event where dozens of community members gathered to learn more about Mr. Adams’s story and its legacy. The soil collected was incorporated into a local exhibit at the Smoky Hill Museum in Salina. A second jar of soil was sent to EJI to be featured in the Legacy Museum’s Soil Collection Exhibit.

The historical marker dedication is the culmination of the coalition’s efforts to have Mr. Adams’s story preserved within the community. Sponsors and partners of the marker dedication include the Salina Branch of the NAACP Unit 4041 K-State Extension Office, Barb Young and North Salina Community Development, City/County Commissioners and building authority, Salina VFW, Salina’s mayor, Dr. Trent Davis, Hutton Construction’s Jason Gillig, Abner Perney, the Great Plains Methodist Conference and Bishop Saenz Jr., Mrs. Ramona Malone, Earl Bane Foundation, Smoky Hill Museum, the Kansas Museum Association, and Saline County residents and community leaders. The coalition hopes to advance further public education about equity and justice in Saline County and is planning new projects to meet the needs of marginalized communities in their area.

/

The Rev. Martha Murchison, Sandy Beverly, and the Rev. Delores “Dee” Williamston, all of whom helped organize the event honoring Mr. Adams, deliver final remarks.

Clay Wirestone/Kansas Reflector

/

A jar with soil collected in memory of Dana Adams sits on display at the Smoky Hill Museum in Salina.

Charles Rankin/The Salina Journal

/

Community members in Salina, Kansas, gather on October 24, 2021, to collect soil memorializing Dana Adams, who was lynched in 1893.

Clay Wirestone/Kansas Reflector

/

Flowers left at Mr. Adams’s grave in the Gypsum Hill Cemetery.

Martha MurchisonLynching in America

Between 1865 and 1950, at least 6,500 Black people were victims of lynchings in the U.S., including at least 22 documented victims of racial terror lynching in Kansas.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, emancipated Black people began migrating to Kansas from Southern states in pursuit of freedom and rights as citizens. As in communities nationwide, many white Kansans opposed equal rights for Black people and participated in intimidation and violent repression in order to maintain white economic, political, and social control.

White lynch mobs displayed a complete disregard for the legal system by seizing Black people from police custody. Law enforcement were armed and charged with protecting Black people in their custody, but they frequently failed to intervene.