Today, the Community Remembrance Project of Greenville County, South Carolina, in partnership with EJI, dedicated a new historical marker in memory of Tom Keith, an older Black man who was lynched by a white mob on August 16, 1899, in Greenville. The marker was installed near Mt. Sinai Baptist Church, located at 1101 Roe Ford Road, on property owned by Furman University. Local research indicates that Mr. Keith was likely captured along Roe Ford Road by the white mob who lynched him and threw his body in the Saluda River.

At least 160 community members attended the dedication ceremony to memorialize Mr. Keith, including representatives from the city council, Furman University, and local institutions and faith communities. Loretta Holloway, South Carolina’s Official First Lady of Song, wove together themes of remembrance, tragedy, and working to overcome injustice through a unique rendition of Strange Fruit and a stunning performance of Dream the Impossible Dream. Speakers at the ceremony focused on the importance of recognizing the legacy of racial injustice in Greenville and underscored that hope for a more just and equitable community requires looking honestly at the past to better understand and respond to present challenges.

The Lynching of Tom Keith

On the night of August 16, 1899, a white mob lynched an elderly African American man named Tom Keith after he was accused of falling asleep in the same room with white children. Mr. Keith, who was described in news reports as “old and trusted,” lived in the home of his white employer, J. B. Hawkins Jr., and worked as a long-time employee on Hawkins’s farm in Greenville.

On August 16, news spread that Mr. Hawkins had found Mr. Keith asleep in the same room as his daughter and son. He reportedly struck Mr. Keith on the head with a gun, waking him violently. Mr. Keith explained that he must have wandered into the room by accident after drinking the night before. When he was told to pack his things and leave town or else Hawkins “would kill him,” Mr. Keith left.

When the story reached Mr. Hawkins’s white neighbors, they became enraged and organized a mob of white men to find Mr. Keith. Available reports do not confirm exactly where the mob found Mr. Keith, but it likely captured him somewhere along or near what is now Roe Ford Road. The mob tied Mr. Keith to a tree, shot him multiple times, and weighed down his body with stones, and threw him into the Saluda River.

Many Black people were lynched based on unconfirmed suspicions of wrongdoing before they ever had a chance to stand trial or defend themselves. No one who participated in the mob was held accountable for Tom Keith’s lynching.

Community Remembrance Project of Greenville, South Carolina

In 2019, members of the Diversity Leaders Institute of the Riley Institute at Furman University reached out to EJI to launch a Community Remembrance Project effort in Greenville. After learning more about the work and its goals, those members helped to build a broader local community coalition that became the Community Remembrance Project of Greenville, South Carolina.

To date, the coalition has advanced soil collection experiences and public education events in memory of four lynching victims documented in Greenville County between 1877 and 1950—George Green, Tom Keith, Ira Johnson, and Robert Williams.

Mr. Keith’s marker is the first marker dedicated to victims of racial terror lynching killed in Greenville County, and the coalition plans to advance additional markers to memorialize Mr. Green, Mr. Johnson, and Mr. Williams. The coalition is also participating in EJI’s Racial Justice Essay Contest. Public high school students are invited to discuss the history of racial injustice and the impact of that history today.

/

Dr. Feliccia Smith, Co-Chair of the Community Remembrance Project of Greenville County, speaks during the marker unveiling ceremony.

Jessica Gallagher/Greenville News

/

Attendees at the marker unveiling ceremony honoring Tom Keith, who was lynched in 1899.

Jessica Gallagher/Greenville News

/

EJI Project Manager Gabrielle Daniels speaks during the ceremony marker dedication ceremony.

Jessica Gallagher/Greenville News

/

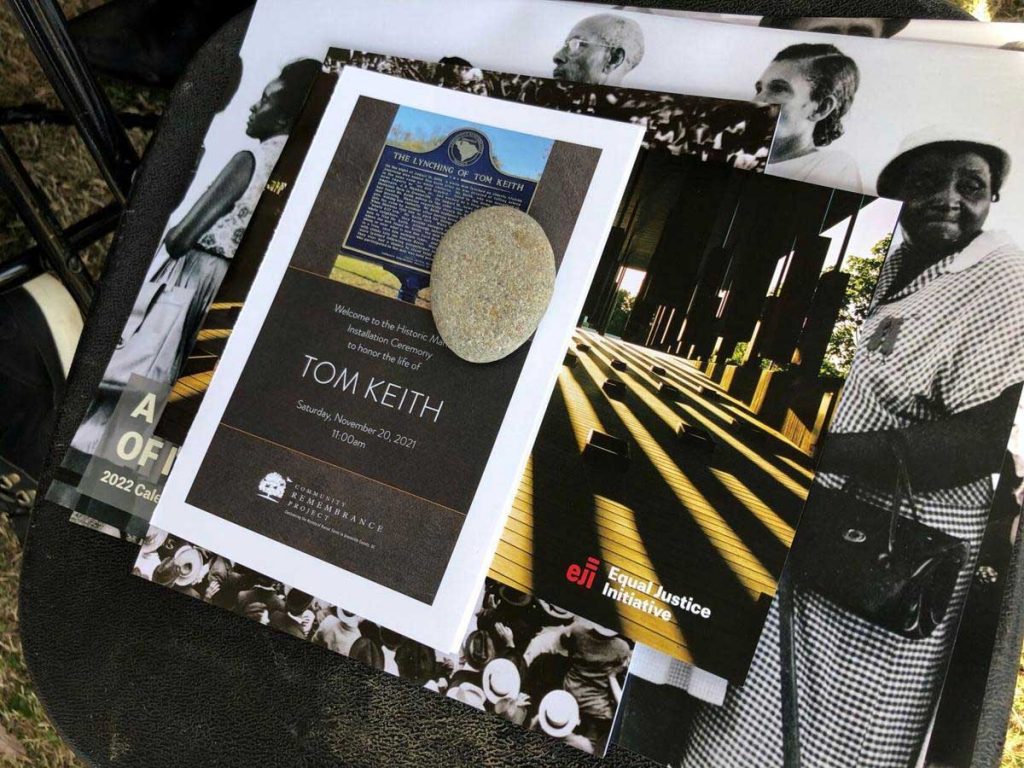

Materials distributed during the marker dedication ceremony honoring Tom Keith.

Freeman Stoddard/Fox Carolina

/

Loretta Holloway, South Carolina’s First Lady of Song, performs during the ceremony memorializing Mr. Keith.

Jessica Gallagher/Greenville NewsLynching in America

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. After slavery ended, many white people remained committed to racial hierarchy and used lethal violence and terror against Black communities to maintain a racial, economic, and social order that oppressed and marginalized Black people. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and created a legacy of injustice that can still be felt today.

Many African Americans were lynched after exercising their civil rights, defying racial social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or being accused of crimes, even when there was no evidence to support the accusation. Racial terror lynching was generally tolerated by law enforcement and elected officials, who were often complicit in these tragedies. Denied equal protection under the law, lynching victims were regularly pulled from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or police custody by white mobs who faced no legal repercussions.

Racial terror lynchings often included burnings and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands. In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South, never to return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Although many victims remain unknown, at least 189 racial terror lynchings have been documented in South Carolina.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching and advance honest conversation about the legacy of racial terror by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and inviting community members to visit the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, where the horrors of these racial injustices are acknowledged.

Through the Community Remembrance Project, EJI has joined with dozens of communities to install historical markers where the history of lynching is documented in our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face, from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, and police violence to the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that continues to burden people of color today.