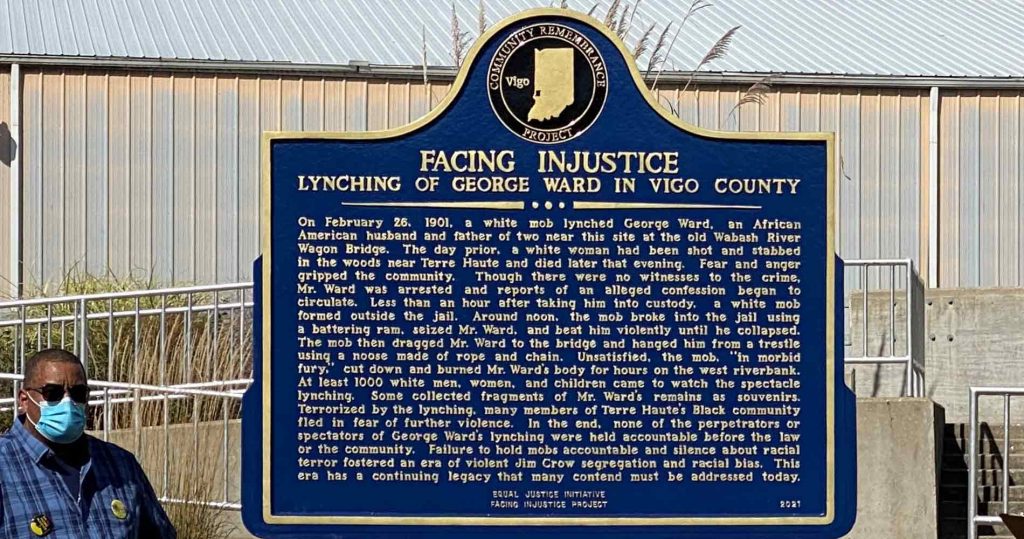

A historical marker in memory of George Ward, a Black man who was lynched by a white mob in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1901, was unveiled and dedicated by the Facing Injustice project of the Greater Terre Haute NAACP Branch in partnership with EJI. The marker is located at 100 Dresser Drive in North Fairbanks Park, near the site of the jail from which Mr. Ward was abducted and the river bridge where he was hanged by the mob.

Over a hundred community members gathered on September 26 to memorialize Mr. Ward, including representatives from local schools, faith institutions, justice organizations, and local officials. Sisters of Providence of St. Mary-of-the-Woods and Girl Scout Troop 10253 greeted guests and invited them to paint rocks that could be left at the base of the marker as a commitment to justice.

More than a dozen descendants of Mr. Ward were in attendance, including his great-grandson, Terry Ward, who spoke on behalf of the family. “You have pierced the dark cloud in this city with a red light of hope,” he said. “Our desire is to open the eyes of the people today to the injustices of the past, so the future will never have to experience these atrocities again.”

State Senator Jon Ford and members of the Indiana Black Legislative Caucus read Indiana State Resolution 72, which was adopted in April 2021 to memorialize George Ward upon the 120th anniversary of his death. “While the past cannot be rectified,” the resolution states, “understanding and recognizing Indiana’s share in the history of lynching is necessary to begin the healing process and prevent similar actions in the future.”

Terre Haute Mayor Duke Bennett also took part in the ceremony, reading the marker language aloud for the crowd alongside Sylvester Edwards, the Greater Terre Haute NAACP President.

The marker was unveiled by Jacqueline Stewart and Ronald Cooper, both descendants of George Ward. Following the marker unveiling, attendees were invited to walk together across the river bridge to the site where Mr. Ward was hanged.

The Lynching of George Ward

On February 26, 1901, a white mob lynched George Ward, an African American husband and father of two, near the old Wabash River Wagon Bridge. The day prior, a white woman had been shot and stabbed in the woods near Terre Haute and died later that evening. Fear and anger gripped the community.

Though there were no witnesses to the crime, Mr. Ward was arrested and reports of an alleged confession began to circulate. Less than an hour after he was taken into custody, a white mob formed outside the jail.

Around noon, the mob broke into the jail using a battering ram, seized Mr. Ward, and beat him until he collapsed. The mob then dragged Mr. Ward to the bridge and hanged him from a trestle using a noose made of rope and chain.

Unsatisfied, the mob, “in morbid fury,” cut down and burned Mr. Ward’s body on the west riverbank. At least 1,000 white men, women, and children came to watch the spectacle lynching. Some collected fragments of Mr. Ward’s remains as souvenirs.

Terrorized by the lynching, many members of Terre Haute’s Black community fled in fear of further violence.

None of the perpetrators or spectators were held accountable before the law or the community. Failure to hold mobs accountable fostered an era of violent Jim Crow segregation and racial bias. This era has a continuing legacy that endures today.

Facing Injustice

In 2019, community members from across Vigo County came together to form Facing Injustice, a group dedicated to remembering and memorializing George Ward. The coalition grew out of the Greater Terre Haute NAACP Branch and is composed of numerous locally engaged community members and activists from various backgrounds, including Mr. Ward’s descendants.

The coalition is helping to advance local remembrance, host community discussions, and raise awareness about the importance of contemporary conversations that address issues of race, poverty, and inequality in Terre Haute and Vigo County.

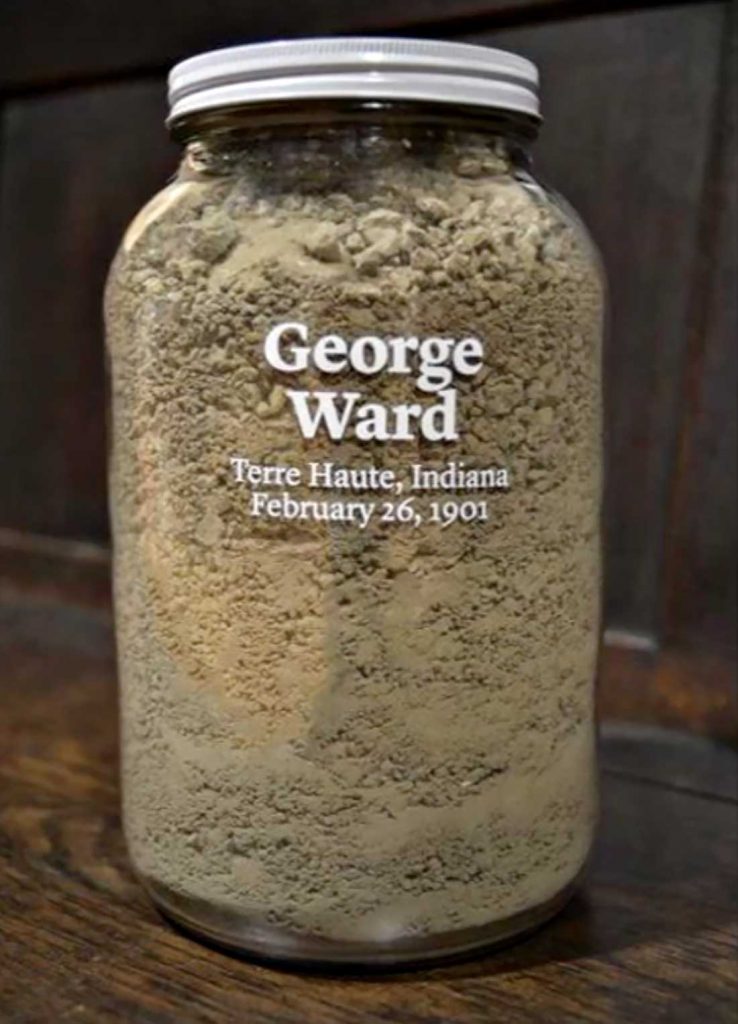

Since its formation, Facing Injustice has hosted numerous public education and engagement events. In March 2020, the coalition conducted a soil collection ceremony in North Fairbanks Park to memorialize Mr. Ward.

/

Terry Ward, whose great-grandfather George Ward was lynched in 1901, speaks during the marker dedication ceremony honoring his ancestor.

/

Terre Haute NAACP President Sylvester Edwards speaks during the marker dedication ceremony honoring George Ward.

Bailey Fay Photography

/

EJI staff, community members, and descendants of George Ward add soil to jars commemorating Mr. Ward.

/

A jar with soil collected in Terre Haute, Indiana, to memorialize George Ward.

/

The newly unveiled historical marker Vigo County, Indiana.

Lynching in America

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. After slavery ended, many white people remained committed to racial hierarchy and used lethal violence and terror against Black communities to maintain a racial, economic, and social order that oppressed and marginalized Black people. Lynching became the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and created a legacy of injustice that can still be felt today.

Many African Americans were lynched after exercising their civil rights, defying racial social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or being accused of crimes, even when there was no evidence to support the accusation. Racial terror lynching was generally tolerated by law enforcement and elected officials who were often complicit in these tragedies. Denied equal protection under the law, lynching victims were regularly pulled from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or police custody by white mobs who faced no legal repercussions.

Many Black people like George Ward were lynched for alleged social transgressions with no allegation of any legitimate crime. Racial terror lynchings often included burnings and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands. Although many victims of racial terror lynching will never be known, at least 11 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Indiana between 1877 and 1950.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. The historical marker in Terre Haute is among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI to date.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.