Hundreds of people joined the Lee County Remembrance Project on June 12 for a ceremony to celebrate the unveiling of a historical marker in historic downtown Opelika’s Courthouse Square. The marker memorializes the lynching of four Black people—John Moss, George Hart, Charles Humphries, and Samuel Harris. LCRP also plans to memorialize Charles Miller, the county’s fifth documented lynching victim.

The ceremony took place at First United Methodist Church and included remarks from coalition members, community members, the local NAACP chapter, and local officials. To conclude the program, attendees walked to the square, where coalition members Ashley Brown, Olivia Nichols, Patricia Butts, Jean Madden, and Harriette Huggins unveiled the marker.

The Lynchings of John Moss, George Hart, Charles Humphries, and Samuel Harris

Between 1877 and 1950, white mobs lynched at least 361 African Americans in Alabama. At least five Black people were lynched in Lee County.

During this era, Black people faced a presumption of guilt that made them vulnerable to accusations of crime and mob violence, often without investigation. In 1886, cousins John Moss and George Hart were part of a search party that found the body of a missing white man in Waverly. Rather than being celebrated for their efforts to locate the missing man, race-based suspicion soon turned to John Moss and George Hart. Hearing that a lynch mob accused them of the murder, the cousins attempted to get to safety. On November 3, the white mob kidnapped Mr. Moss. Despite his pleas of innocence, the mob tortured him, hanged him, and burned his body.

Montgomery Advertiser, November 7, 1887

Mr. Hart was seized in a “citizen’s arrest” and taken to the Montgomery jail to avoid mob violence. On November 1, 1887, he was returned to Opelika for trial. News soon broke that the evidence against Mr. Hart was not strong enough for a conviction. On November 5, over 60 armed white men kidnapped him from the Opelika jail.

Although legally required to protect people in their custody, police were often indifferent to or ineffective at protecting Black people. The white mob hanged Mr. Hart from the same tree as John Moss and pinned a placard to his back. It read: “This negro was hung by 100 determined men; whoever cuts him down will suffer his fate.”

Local officials, including local law enforcement, were complicit in each of these lynchings. No one was ever held accountable.

On November 3, 1902, an armed white mob seized Samuel Harris, a Black man who was picking cotton in a field when two white women reported a robbery and assault nearby in Salem. Hours later, despite having no evidence that implicated Mr. Harris in the crime, over 125 men shot him to death. His pregnant wife, Beatrice, was arrested as an accomplice. Newspapers did not report what happened to Mrs. Harris after her arrest.

On March 18, 1900, a white mob lynched Charles Humphries. The previous day, a white teenager reported being startled when she saw Mr. Humphries, a young Black employee of her father, in her room. The mob went to Mr. Humphries’s home near Phenix City and shot him more than 40 times.

During this era, white people’s fears of interracial sex extended to any action by a Black man that could be interpreted as seeking contact with a white woman.

White communities were often supportive of violence against Black people, and the lynchings of many victims were not recorded and remain unknown. Lynching inflicted lasting traumatic wounds for Black people in the South and thousands fled the region as refugees from racial terrorism.

Lee County Remembrance Project

The Lee County Remembrance Project began its work under the leadership of Ashley Brown, Olivia Nichols, and Patricia Butts in 2018. The coalition planned an in-person Soil Collection Ceremony for March 2020 but had to postpone due to Covid-19. On November 5, 2020, LCRP hosted a hybrid virtual and in-person Soil Collection Ceremony that included videos honoring each victim, music from the Auburn Gospel Choir, a dramatic presentation by Mosaic, and a responsive lament.

The work of LCRP also includes the creation of an educational booklet about each of the lynchings in the county. The coalition is engaged in ongoing research to uncover additional undocumented lynchings in Lee County.

Racial Justice Essay Contest

LCRP partnered with EJI to host a Racial Justice Essay Contest open to all public high school students in the county. Students attending public high school in Lee County, were invited to compete for prizes totaling $6,000. LCRP hosted panels and workshops during the essay contest period to support students in their research and learning.

The five winners and three honorable mentions were honored at the marker ceremony, and first place winner Mary Ellen Lancaster read her essay during the ceremony. The winners included Caderria Thomas (2nd Place), Braxton Harris (3rd Place), Jireh Ray (4th Place), Jahunna Neston (5th Place), and Miles Hunt, Clara Ragan, and Dayzjah Walton (Honorable Mentions).

In collaboration with LCRP, the local NAACP chapter has agreed to provide financial support to continue the contest annually.

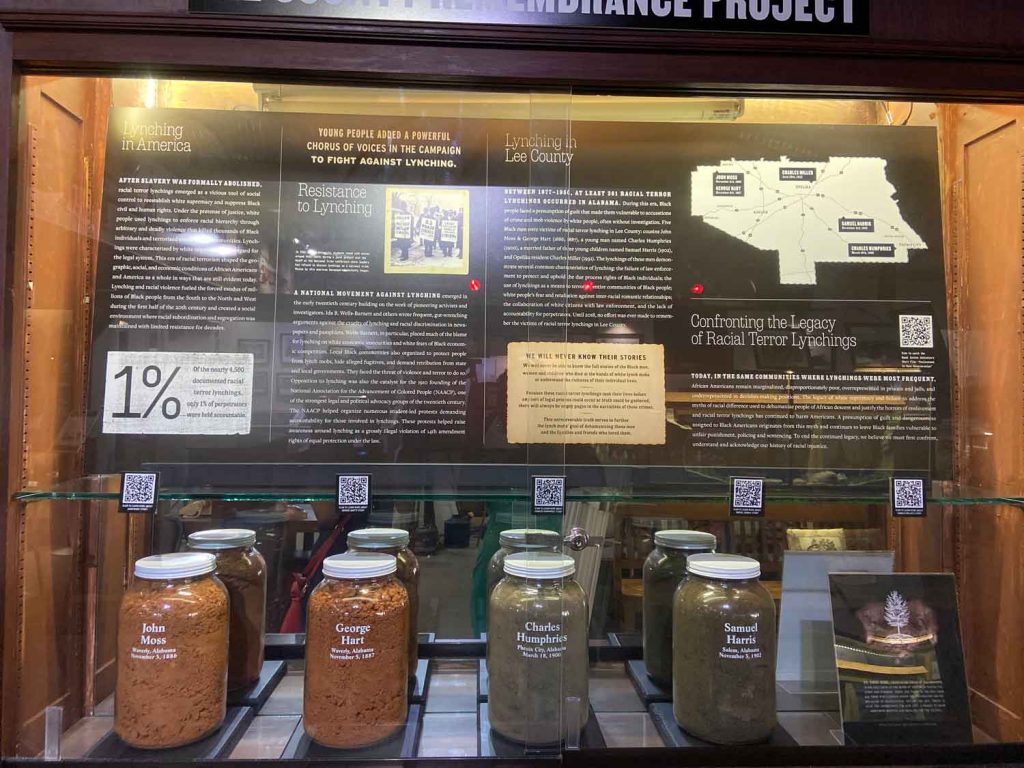

Local Exhibit at the Museum of East Alabama

As part of its public education work, LCRP used its educational booklet about each of the lynchings in the county to curate a local exhibit of soil at the Museum of East Alabama. The exhibit includes soil jars from the coalition’s Soil Collection Ceremony as well as information about each of the five documented lynching victims in the countym – John Moss, George Hart, Charles Humphries, Samuel Harris, and Charles Miller. The coalition invites people to visit the exhibit.

/

Members of the Lee County Remembrance Project unveil the historical marker honoring John Moss, George Hart, Charles Humphries, and Samuel Harris.

G. Robert Noles

/

Bill Allen, coalition co-liaisons Ashley Brown and Olivia Nichols, and Laticia Khalif-Smith, holding a proclamation of support from the Lee County NAACP.

The Fifty Fund

/

Lee County Remembrance Project members and EJI staff stand in front of the newly dedicated historical marker.

The Fifty Fund

/

Jars memorializing victims of racial terror lynchings on display in a soil exhibit in Lee County, Alabama.

Lynching in America

Before the Civil War, millions of African people were kidnapped, enslaved, and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas under horrific conditions that frequently resulted in starvation and death. Over two centuries, the enslavement of Black people in the U.S. created wealth, opportunity, and prosperity for millions of white people in all regions of the country while traumatizing and devastating enslaved Black people who were denied any legal rights or autonomy.

By 1860, enslaved people were 45% of the state population in Alabama. When chattel slavery ended in 1865, racial terror lynching emerged as a lawless and tragic form of violence against Black people used to maintain racial hierarchy. Black people accused of violating social customs, seeking economic and political autonomy, or committing alleged crimes—even when there was no evidence tying the accused to the offense—were often victims of racial terror lynching.

Based on EJI’s Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America research, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. Millions of Black Americans were victimized by this violence, many of whom fled to the urban North and West. Some 360 lynchings of Black people by white mobs have been documented in the state of Alabama.

Community Remembrance Project

The Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of our effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented. The narrative historical marker in Opelika is among dozens of narrative markers sponsored by EJI to date.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.