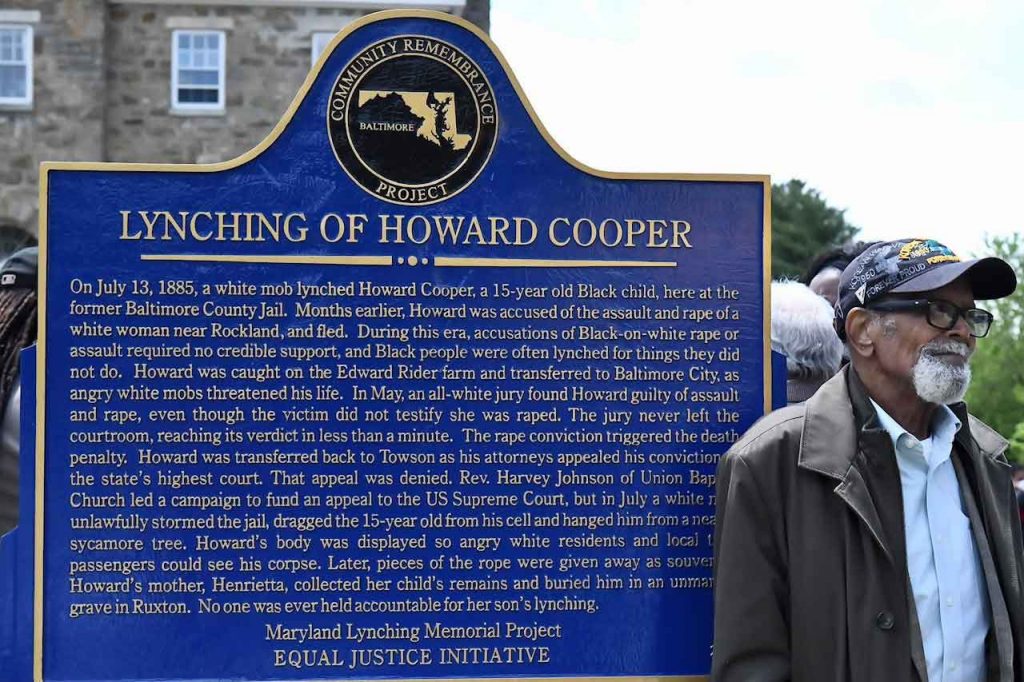

On May 8, the Baltimore County Committee of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project, in partnership with EJI, dedicated a historical marker in remembrance of Howard Cooper, a 15-year-old child who was brutally lynched in Baltimore County in 1885.

Situated in front of the old Baltimore County Jail, the historical marker stands roughly a block away from the Baltimore County Courthouse.

More than a century later, over a hundred people gathered both virtually and in-person at the old Baltimore County Jail to attend the marker dedication ceremony.

The Lynching of Howard Cooper

On July 13, 1885, a white mob lynched Howard Cooper, a 15-year-old Black child, at the old Baltimore County Jail. Months earlier, Howard had been accused of assaulting and raping a white woman near Rockland, and he fled in fear.

During this era, accusations of Black-on-white rape or assault required no credible support, and Black people were often lynched for things they did not do.

The young teen was captured on the Edward Rider farm and transferred to Baltimore City as angry white mobs threatened his life.

In May, an all-white jury sentenced Howard to death, even though the victim never testified that she was assaulted. The jury never left the courtroom, reaching its verdict in less than a minute. The rape conviction triggered the death penalty. Howard was transferred back to Towson as his attorneys appealed his conviction to the state’s highest court. That appeal was denied.

The governor scheduled his execution date for July 31 as the Rev. Harvey Johnson of Union Baptist Church led a campaign to fund an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the early morning hours of July 13, a white mob of at least 75 men unlawfully stormed the jail, dragged the 15-year-old from his cell, and hanged him from a nearby sycamore tree. Howard’s body was displayed so that angry white residents and local train passengers could see his corpse.

A member of the mob reportedly stood atop a barrel and declared, “Boys, the fruit of that tree shows that the men of Baltimore County will protect their wives and daughters. I wish we had [Mr. Cooper’s defense lawyers] swinging up there too.”

Later, pieces of the rope were given away as souvenirs.

Howard’s mother, Mrs. Henrietta Cooper, collected her child’s remains and buried him in an unmarked grave in Ruxton. No one was ever held accountable for her son’s lynching.

Racial Terror Lynching in Maryland

At least 6,500 Black people were the victims of racial terror lynching in the U.S. between 1865 and 1950. The names of many victims of racial terror lynchings will never be known, but EJI has documented at least 29 lynchings in Maryland between 1877 and 1950.

Maryland did not join the Confederacy, but in 1860 more than 87,000 Black people were enslaved in the state, where slavery remained legal. The Emancipation Proclamation did not authorize freedom for enslaved Black people in states outside the Confederacy, like Maryland. Resistance to emancipation by white enslavers in these states was often strong as they believed they should be rewarded for not joining the South’s rebellion.

After the Civil War, violent resistance to equal rights for Black people and an ideology of white supremacy led to fatal violence against Black women, men, and children, who were often falsely accused of violating social norms or crimes.

Racial violence and lynching emerged post-emancipation as a form of terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and reinforce racial hierarchy and segregation. Burdened by presumptions of guilt, thousands of Black people were lynched for resisting exploitation, violating social customs, or being falsely accused. Such “offenses” could be something as trivial as arguing with or insulting a white person. Millions of Black people were forced to flee their homes and lands for more secure communities in the North or West.

As in the case of 15-year-old Howard Cooper, the mere accusation of sexual impropriety, even without an identification by the alleged victim, often aroused a mob and resulted in lynching. Many African Americans were lynched not because they were accused of any crime, but simply because they were black and present when the preferred party could not be located by the white mob.

/

/

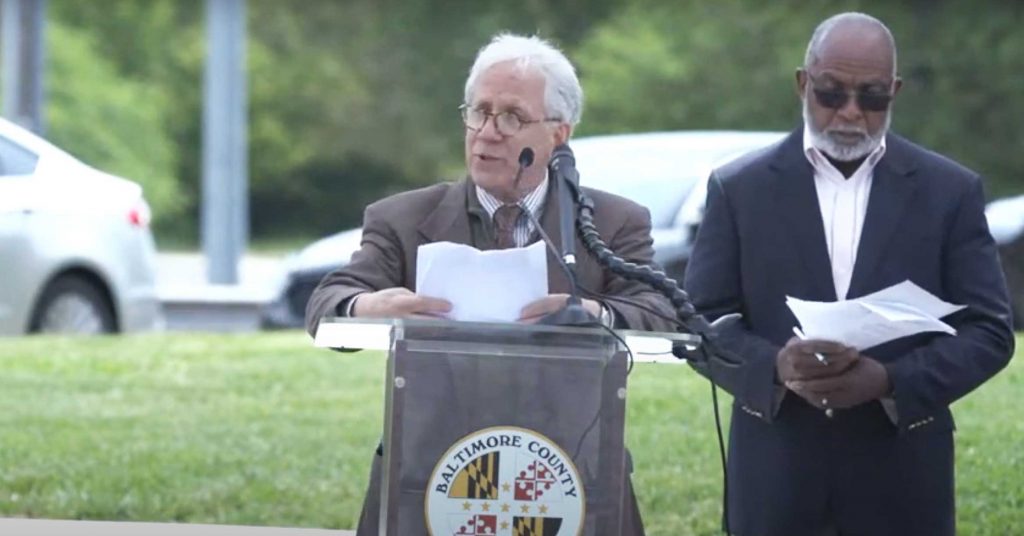

Will Schwarz, President of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project, speaks at the marker unveiling ceremony.

/

Historian Louis Diggs stands next to the marker memorializing Howard Cooper.

/

Tyrell Taylor accepts the first place award for the Racial Justice Essay Contest.

/

Amy Millin and Carol Brooks stand next to the historical marker honoring Howard Cooper.

Maryland Lynching Memorial Project

Following a soil collection community ceremony commemorating Howard Cooper in February 2018, the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project (MLMP) was established. Dedicated to publicly documenting the history of racial terror lynchings across the state, MLMP works to honor and dignify the lives of the victims.

Since the first soil collection in 2018, MLMP President Will Schwarz has mobilized a diverse coalition of people, bringing together hundreds across the state of Maryland to engage in the process of community remembrance. Of the 18 counties where lynchings are documented to have taken place, 14 are partnered with MLMP. The Baltimore Committee of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project has partnered with local cultural sites, faith institutions, and schools committed to sustained outreach and public education efforts about the legacy of racial injustice.

In 2019, Maryland established a statewide commission on racial terror lynchings, acknowledging that at least 40 Black people are documented to have been lynched in Maryland.

“These crimes far exceeded any notion of ‘justice,’ just retribution, or just punishment, but were intended to terrorize African American communities and force them into silence and subservience to the ideology of white supremacy,” the act states.

Aided by the Office of the Attorney General, the commission has been tasked with publicly documenting and memorializing the victims and investigating the role of state, county, and local government and the press in these racially motivated attacks. After three years, the commission will submit its findings and recommendations to the governor.

In conjunction with this 2021 historical marker, the Baltimore County Committee of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project hosted a Racial Justice Essay Contest in collaboration with EJI and awarded a total of $5,000 in scholarships. The winners were Tyrell Taylor (First Place), Fiona Sinphavong (Second Place), Avery Butler (Third Place), Cianna Franklin (Fourth Place) and Aniah Johnson (Fifth Place). Honorable Mentions included Breana Clarke, Leslie Mbiakop, and Luxel (James) Moliko Djouba.

“We may get a little bit further in front of this battle against racism, but it has somehow found a way to ambush African Americans when it is least expected,” said Tyrell Taylor, a ninth grader at Woodlawn High School who read his winning essay entitled “It is More Than Just a Vote.”

To date, this historical marker is the second marker installed in Maryland. In September 2019, EJI partnered with Connecting the Dots Anne Arundel County to install a marker commemorating the lynchings of five Black men: John Simms (1875), George Briscoe (1884), Wright Smith (1898), Henry Davis (1906), and King Johnson (1911). All were killed without trial and many under false accusations. The perpetrators of this violence were often known to law enforcement, and no one was ever convicted of a crime for these acts of racial terror.

Lynching in America

In Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America, EJI has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings in America between 1865 and 1950. Thousands more Black people have been killed by white mob lynchings whose deaths may never be discovered. The lynching of African Americans was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate Black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many Black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of Black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known.

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project

EJI’s Community Remembrance Project is part of our campaign to recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites, erecting historical markers, and developing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice.

As part of its effort to help towns, cities, and states confront and recover from tragic histories of racial violence and terrorism, EJI is joining with communities to install historical markers in communities where the history of lynching is documented.

We believe that understanding the era of racial terror is critical if we are to confront its legacies in the challenges that we currently face from mass incarceration, excessive punishment, police violence, and the presumption of guilt and dangerousness that burdens people of color today.