Judicial Selection

Five states in America—including Alabama—select all of their judges through partisan elections, and 39 states use elections to choose at least some of their judges. In the last two decades, judicial elections have become increasingly expensive, politicized, and dominated by special interest groups.

From 2000-2009, judicial campaign spending totaled $206.9 million—more than double what it had been in the 1990s.1 Alicia Bannon, “Rethinking Judicial Selection in State Courts,” Brennan Center for Justice (2016).

The upward trend in judicial election spending continues: a study by the Brennan Center, a non-partisan public policy institute, found that during the 2013-2014 cycle alone, total spending on our nation’s highest state court races came to $34.5 million dollars across 19 states. Outside spending by special interest groups reached an all-time high of 29% ($10.1 million). Special interest spending proved effective: more than 90% of the contested judicial seats were won by the candidate who spent the most.2 Scott Greytak et al, “Bankrolling the Bench,” Brennan Center for Justice (2015).

Politically Skewed Campaign Contributions

The majority of organizations bankrolling judicial elections are politically conservative: 70% of all expenditures by special-interest groups in the 2013-2014 election cycle went to Republican or conservative candidates. This imbalance is concerning in light of research showing that contributions from interest groups result in the parties associated with those interest groups getting favorable rulings in court.3 Joanna M. Shepherd, “Money, Politics, and Impartial Justice,” Duke Law Journal (2008).

Another concern is that politically skewed campaign contributions will stifle competition and undermine the electoral process. For example, from 2000 to 2009, Alabama led the nation in state Supreme Court candidate fundraising with almost $41 million, nearly doubling the amount raised in second-place Pennsylvania.4 John F. Kowal, “Judicial Selection for the 21st Century,” Brennan Center for Justice (2016). In the 2013-2014 election cycle, Alabama’s candidate fundrasing totaled a mere $41,163 because the judges ran virtually unopposed. The state’s Democratic Party Chair made statements suggesting that Democrats have simply stopped contesting Supreme Court elections, instead devoting their limited resources to other causes.5 Scott Greytak et al, “Bankrolling the Bench,” Brennan Center for Justice (2015).

The Impact On Criminal Justice

Tough on crime rhetoric permeates judicial campaigns. In the most recent election cycle, a record 56% of television advertisements focused on the candidates’ criminal justice records. In addition to accusing each other of being soft on crime, judicial candidates routinely touted their own commitment to punishing criminals.6 Scott Greytak et al, “Bankrolling the Bench,” Brennan Center for Justice (2015).

The persistent emphasis on crime in judicial campaigns affects the rights of those within the criminal justice system. When researchers from the American Constitution Society and Reuters examined over 3000 criminal appeals to state supreme courts in 32 states, they found that in the 15 states where the judges were directly elected, they overturned death sentences in 11% of appeals. In the seven states where judges were appointed, they overturned death sentences in 26% of appeals—more than twice as often.7 Dan Levine and Kristina Cooke, “In States with Elected High Court Judges, a Harder Line on Capital Punishment,” Reuters (Sept. 22, 2015).

As Yale Law School lecturer and defense lawyer Stephen Bright said, “Courts have a responsibility to protect a defendant’s constitutional rights without political pressure, especially when the person’s life is at stake. It’s the difference between the rule of law and the rule of the mob.”

Another study focused on the specific effect of television advertising found that the more television ads air during state supreme court judicial elections, “the less likely justices are to vote in favor of criminal defendants. . . . In a state with 10,000 ads, a doubling of airings is associated on average with an 8 percent increase in justices voting against a criminal defendant’s appeal.”8 Joanna Shepherd and Michael S. Kang, “Skewed Justice: Citizens United, Television Advertising and State Supreme Court Justices’ Decisions in Criminal Cases,” ACS Blog.

Moreover, the study found that the U.S. Supreme Court case Citizens United v. FEC, which prohibited restrictions against independent spending by corporations and other special interest groups, resulted in a 7% decrease in justices voting in favor of criminal defendants in the 23 states where corporate election spending had been previously barred.

This direct connection between campaign spending and legal outcomes is reflected in public opinion: 95% of the public believes that campaign spending impacts judges’ rulings. Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor described this as a “crisis of confidence in the impartiality of the judiciary.” If left unaddressed, she argued, “the perception that justice is for sale will undermine the rule of law that the courts are supposed to uphold.9 James Sample et al, “The New Politics of Judicial Elections, 2000-2009,” Brennan Center for Justice (2010).

Race and Gender in the Judiciary

State-level judicial selection systems that favor those backed by wealthy organizations and corporations perpetuate the underrepresentation of people of color and women in state courts.

A recent study by the American Constitution Society found that 80% of all state court judges are white, while only 7% are Black and only 5% are Latino.10 Tracey E. George and Albert H. Yoon, “The Gavel Gap: Who Sits in Judgment on State Courts?” American Constitution Society.

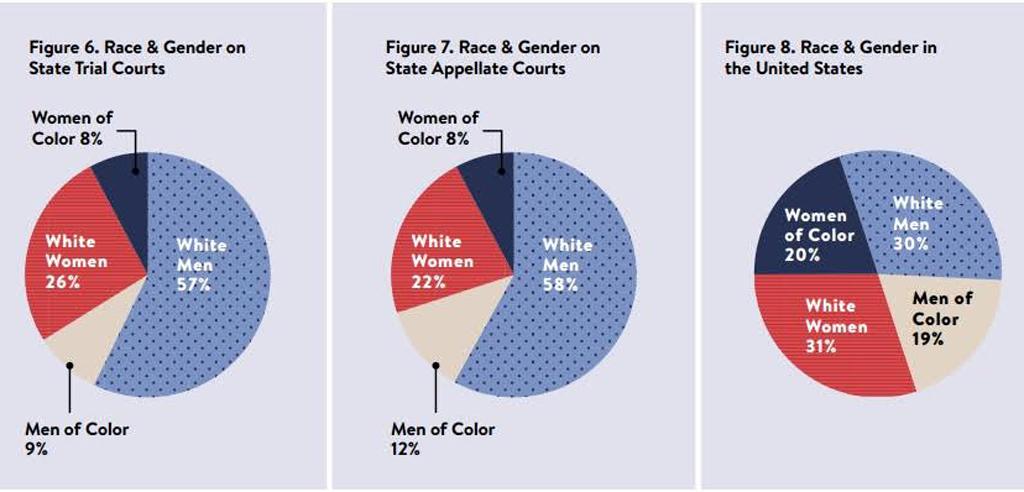

Women are also underrepresented at the state level: they constitute slightly over half of the country’s population, yet they account for less than one-third of the judiciary. Women of color are represented at only 40 percent of their relative numbers in the general population, while the ratio of white men on state benches is nearly double their relative number in the general population.

Source: The Gavel Gap

Given these numbers, it is not surprising that less than one-third of African Americans believe that state courts provide equal justice, compared to 57% of Americans as a whole. The American Bar Association concluded that “lower levels of public confidence in the courts among African American citizens signal a very serious problem that will only get more acute as our population becomes increasingly diverse, unless something is done about it now.”11 Alfred P. Carlton Jr., “Justice in Jeopardy,” American Bar Association Commission on the 21st Century Judiciary (July 2003).

Reform is needed in many state courts across the country. All states should switch to non-political, non-partisan selection of judges in order to remove political pressure and the influence of money from the judicial selection process. These steps are ultimately needed to restore the independence and credibility of the judiciary, and to protect the rights of every person who stands before the law.