Unreliable Verdicts

Racial Bias and Wrongful Convictions

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

For much of the summer and early fall of 2024, as the State of Missouri prepared to kill him, Marcellus Williams was a topic of national news. Mr. Williams, 55, had consistently declared his innocence throughout more than 20 years on death row for the 1998 murder of a white woman named Felicia Gayle. But now, a media spotlight shone upon the unique collection of allies working to save his life: trial jurors no longer in support of the death sentence; former prosecution witnesses who had since recanted their testimony; and even a county prosecutor willing to impose a sentence of life imprisonment instead.

The legal briefs and newspaper headlines emphasized arguments over improperly withheld evidence, recanted witness testimony, DNA testing, and the morality of capital punishment. But one question with major implications for the reliability of Mr. Williams’s conviction and sentence received comparably little attention: were Black jurors systematically excluded from serving in the case?

At Mr. Williams’s trial, the pool of potential jurors included seven Black people.

State prosecutors rejected six—including one young Black man the State did not want on the jury because the potential juror and Mr. Williams “looked like they could be brothers.”1 Katie Moore, “Man Scheduled for Execution Next Week in Missouri Says his Trial Excluded Black Jurors,” Kansas City Star, Sept. 17, 2024.

As a result, in St. Louis in 2001, a Black man was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by a 12-member jury that included just one Black person.2 Moore, “Excluded Black Jurors.” At the time, St. Louis County was 20% Black.3 “Our Changing Population: St. Louis County, Missouri,” USA Facts, accessed Feb. 7, 2025.

Twenty-three years later, the sitting prosecuting attorney for St. Louis County supported efforts to stop Mr. Williams’s execution and acknowledged that lawyers working for the office in 2001 had displayed racial bias when choosing the jury. Such misconduct, the prosecutor’s filing argued, “undermines confidence” in Mr. Williams’s conviction and death sentence.4 Natalie Neysa Alund, “Marcellus Williams’ Missouri Execution to Go Forward Despite Prosecutor’s Concerns,” USA Today, Sept. 12, 2024.

Marcellus Williams died by lethal injection on September 24, 2024, after reviewing courts and other authorities declined to intervene. Just one day before the execution, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson defended his choice to do nothing.

“The facts are, Mr. Williams has been found guilty, not by the governor’s office, but by a jury of his peers, and upheld by the courts.”5 Sam Levin, “Missouri to Execute Marcellus Williams Despite Prosecutors’ Objections and Innocence Claims,” Guardian (US edition), Sept. 24, 2025.

Like the governor’s statement—which made no mention of the racial makeup of Mr. Williams’s jury or the prosecution’s admission of bias—modern defenses of criminal law, mass incarceration, and the death penalty regularly reference jury decision-making as inherently sound, dignified, and sacred. In 1774, future president John Adams wrote, “Representative government and trial by jury are the heart and lungs of liberty.”6 John Adams, The Revolutionary Writings of John Adams, ed. C. Bradley Thompson (Liberty Fund, 2000), 55. The citizen jury has long been a bedrock of America’s constitutional system, lauded by founding fathers and Supreme Court justices alike.

Of course, “representative” and “jury of one’s peers” have curious meanings when, for much of this nation’s history, the methods used to select juries were strict, narrow, sexist, and racist.

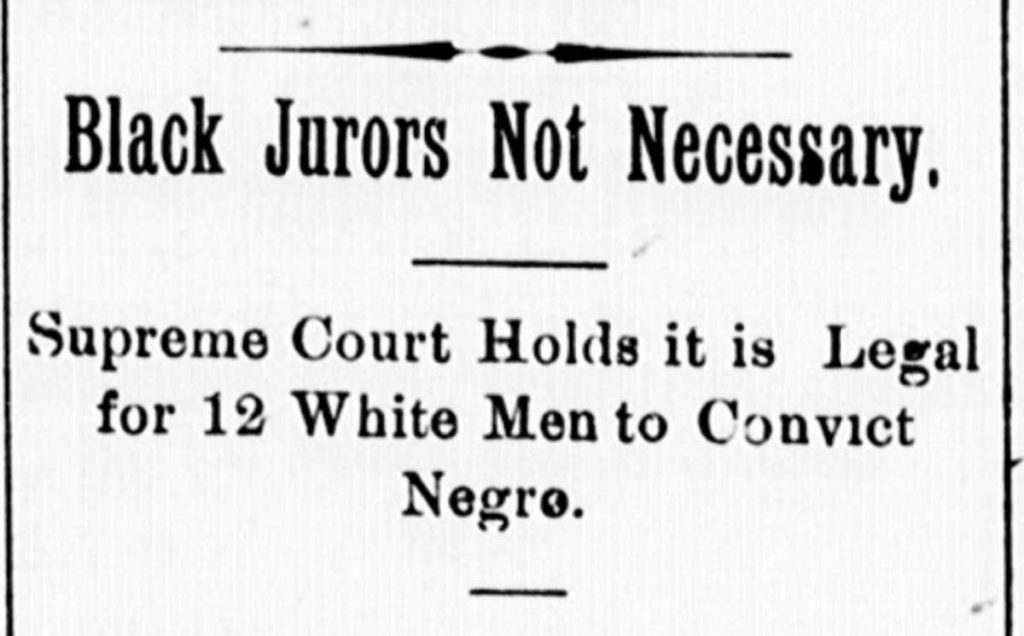

Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th centuries, just as the stereotype of the “Black criminal’’ grew increasingly common and widespread, jury trials were among the primary tools used to enforce criminal law, and a “good jury” was invariably male and white. In 1986, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Batson v. Kentucky established a procedure for courts to intervene when racial bias impacts jury selection.

Nevertheless, jury discrimination remains widespread today.

And though modern research endorses the value of diverse juries, they remain rare and elusive, even in death penalty cases where the risk of error is greatest.

This report briefly reviews the history of jury discrimination and the limited success of efforts to address it through legal procedure over the past 40 years. Next, we examine growing research on the positive impact of jury diversity when it comes to reducing bias and encouraging probing, rigorous deliberation. Then, acknowledging the considerable obstacles to compiling a comprehensive, reviewable dataset, we discuss the pool of documented death penalty exonerations and examine several such cases decided by nondiverse juries.

Finally, we turn to the cases of individuals currently on Alabama’s death row to analyze how often those convictions were reached by nondiverse juries. And we ask—in light of the research and wrongful conviction anecdotes already discussed—should we believe those verdicts reliable enough to justify death?

This report is produced, prepared, and distributed by the Equal Justice Initiative. Senior Attorney and Senior Writer Jennifer Rae Taylor wrote the report and served as lead researcher. Multiple EJI staff assisted with research, editing, layout, design, and distribution.

Chapter 1

What Makes a Juror?

The U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to be tried by a jury of one’s peers as a safeguard against abuses of power by state and federal governments. The jury trial empowers ordinary citizens to play a central role in weighing evidence and, in some cases, deciding the proper sentence. In doing so, juries can help limit and oversee the actions of prosecutors, judges, and even lawmakers.

“Other than voting,” the U.S. Supreme Court explained in 2019, “serving on a jury is the most substantial opportunity that most citizens have to participate in the democratic process.”7 Flowers v. Mississippi, 588 U.S. 284, 293 (2019).

But how a jury functions and what purpose it serves depends in part on who is chosen to serve. Jury service is a right of citizenship—and like voting and holding elected office, Americans’ ability to exercise that right has historically been shaped by racial discrimination.

When the Constitution was formally adopted in 1789, more than 90% of Black people in America were enslaved.8 U.S. Census Bureau, “Black and Slave Population of the United States from 1790 to 1880,” Bicentennial Edition: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (2019), 14. That meant they were denied citizenship, legally classified as property, and in no way included in the legal concept of a jury of fellow citizens. Slavery remained legal in the country for another 76 years and, during that time, even free Black people had a tenuous citizenship status. Most state laws used race as a qualification for serving on juries or receiving a jury trial.9 See, e.g., An Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves (1690), in The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, ed. David McCord, vol. 7 (Columbia: 1840), 343-47; An Act for the More Speedy Prosecution of Slaves Committing Capital Crimes (1692), in Statutes at Large; Being A Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, ed. William Henning, vol. 3 (Richmond: 1823), 102-03; An Act for the Trial of Negroes (1700), in The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801 2, eds. James T. Mitchell and Henry Flanders (Harrisburg: 1896), 77-78 (limiting jury service to freeholders, for trials of Black people); State v. Ben, 8 N.C. 434, 435-36 (1821) (describing North Carolina’s system, which denied enslaved people the right to jury trial); An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing Negroes and Other Slaves in this Province (1755), in The Colonial Records of the State of Georgia, ed. Allen Candler, vol. 18 (Atlanta: 1910), 102, 108-110 (limiting jury service in trials of free and enslaved Black people to freeholders). Other laws prohibited free and enslaved Black people from testifying in court, making exceptions only in cases involving charges against other Black people, where “other evidence proved insufficient,” or where the charges involved conspiracy to harm a white person. See, e.g., An Act For Regulating of Slaves (1702), in The Colonial Laws of New York from the Year 1664 to the Revolution, ed. J.B. Lyon, vol. 1 (Albany, 1894), 519-21; An Act Relating to Servts [sic] and Slaves (1715), in Archives of Maryland, Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly of Maryland April 1715-August 1716, ed. William Browne vol. 30 (Maryland Historical Society, 1910), 283-92; Against Whom Slaves and Other Persons of Colour May Be Witnesses (1777) in An Act Concerning Slaves and Free Persons of Color, Revised Code of North Carolina No. 105 (1855). Though Black jurors were exceedingly rare while slavery persisted, many Black people already understood that jury service would be critical and necessary to achieve true freedom.

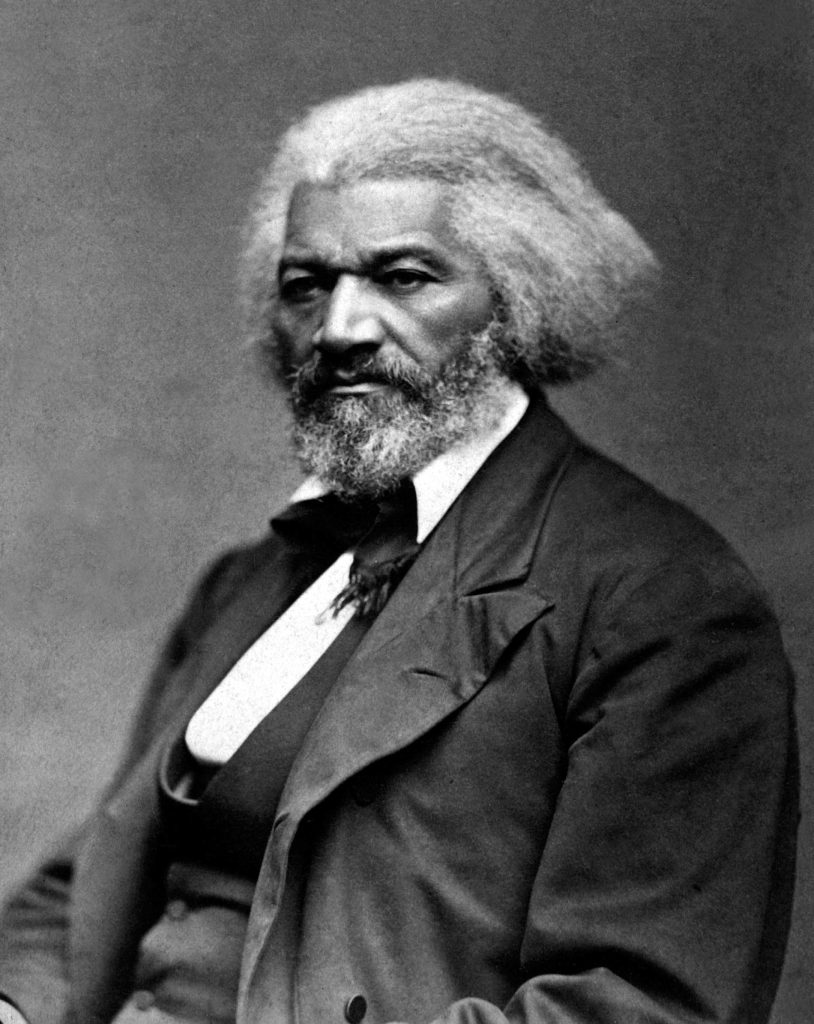

“To guard, protect, and maintain his liberty, the freedman should have the ballot,” Frederick Douglass declared in a memoir discussing his own escape from enslavement in 1838. “The liberties of the American people were dependent upon the Ballot-box, the Jury-box, and the Cartridge-box.”10 Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882, ed. John Lobb (London, 1882), 332-33. For discussion of Black Americans’ fight to serve on juries before the Civil War, see Thomas Ward Frampton, “The First Black Jurors and the Integration of the American Jury,” N.Y.U. Law Review 99 (2023): 515.

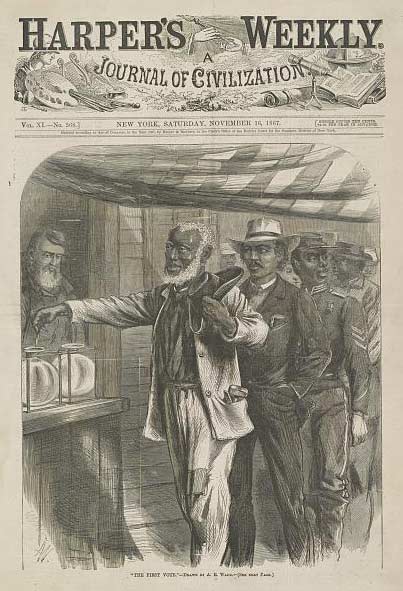

From 1861 to 1865, the United States fought a Civil War sparked by sectional tensions and increasing Southern white anxiety that federal officials would force an end to slavery. The war ended with the rebelling South’s defeat and surrender, and the Reconstruction Era began with changes to the Constitution. In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery.11 The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery “except as punishment for crime.” Soon after, in 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to Black people born in the country and guaranteed all citizens equal civil rights and legal protections. Then, in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment barred states from basing voter eligibility on race.

By the summer of 1867, just two years after the abolition of slavery, 80% of Black male voters living in 10 of the 11 former Confederate states were registered to vote.12 Henry Louis Gates Jr., “The ‘Lost Cause’ That Built Jim Crow,” New York Times, Nov. 8, 2019.

In 1875, Congress passed a Civil Rights Act that formally outlawed race-based discrimination in jury selection.13 The Civil Rights Act of 1875, ch. 114, § 4, 18 Stat. 336 (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. § 243).

But these legal and constitutional reforms did not usher in an immediate and enduring period of fully realized Black citizenship—especially after Reconstruction ended in 1877. As Union forces withdrew from the Southern states, former Confederate leaders whose racial and political views had changed little since the Civil War were again empowered to make and enforce laws. Eradicating Black Americans’ civil rights was their immediate goal.

“What is it that we want to do? Why, it is, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this State,” declared John B. Knox during proceedings to write a new Alabama Constitution after Reconstruction. “But if we would have white supremacy, we must establish it by law—not by force or fraud.”14 Alabama Constitutional Convention (1901), Official Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Alabama: May 21st, 1901, to September 3rd, 1901 (Wetumpka Printing Co., 1940).

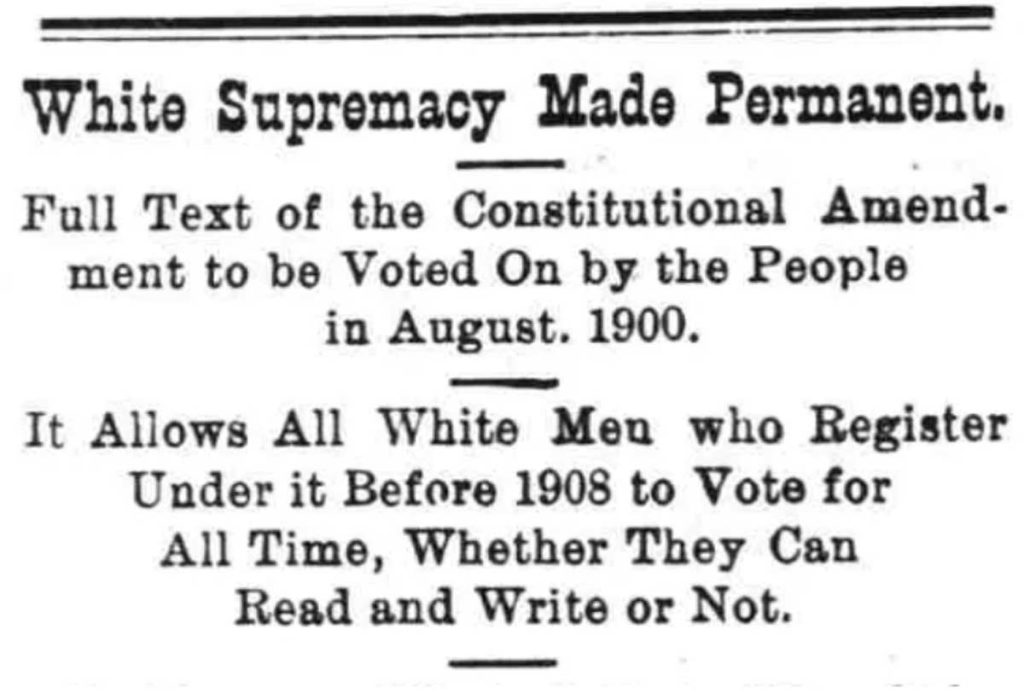

From 1885 to 1908, all 11 former Confederate states rewrote their constitutions to restrict voting rights using poll taxes, literacy tests, and felony disenfranchisement.15 Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disenfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908 (University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 1, 6. Alabama and other Southern states quickly crafted legal ways to evade the Fifteenth Amendment’s ban on race-based voting discrimination. Lawmakers passed “race-neutral” policies deemed legal on paper, then gave white registrars broad discretion to apply the laws in ways that drastically limited Black people’s ability to register and vote.

Coupled with economic intimidation and violent racial terror, Black political rights all but disappeared in the South.16 See Equal Justice Initiative, Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence after the Civil War (2020) (“Just by daring to venture into the light of freedom and opportunity, Black men, women, and children who exercised the rights gained through federal legislation and the Reconstruction Amendments became targets of deadly racial violence wielded by white people determined to ensure freedom would be anything but a joyful story.”).

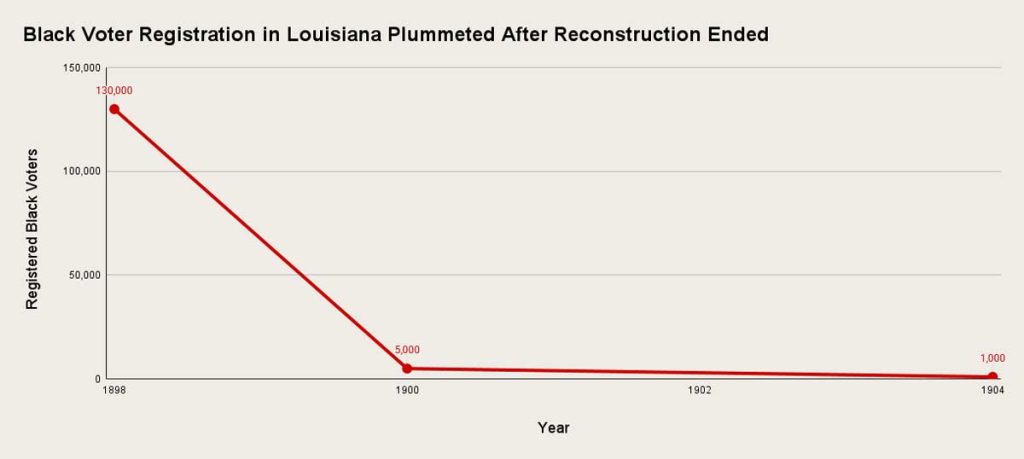

During Reconstruction in Louisiana, 130,000 Black voters were registered to vote. After Reconstruction ended and the state passed “race-neutral” voting restrictions, the number of Black registered voters plummeted to 5,000 by 1900, and just 1,000 by 1904.17 Daniel Brantley, “Blacks and Louisiana Constitutional Development, 1890-Present: A Study in Southern Political Thought and Race Relations,” Phylon 48, no. 1 (1987): 51-61.

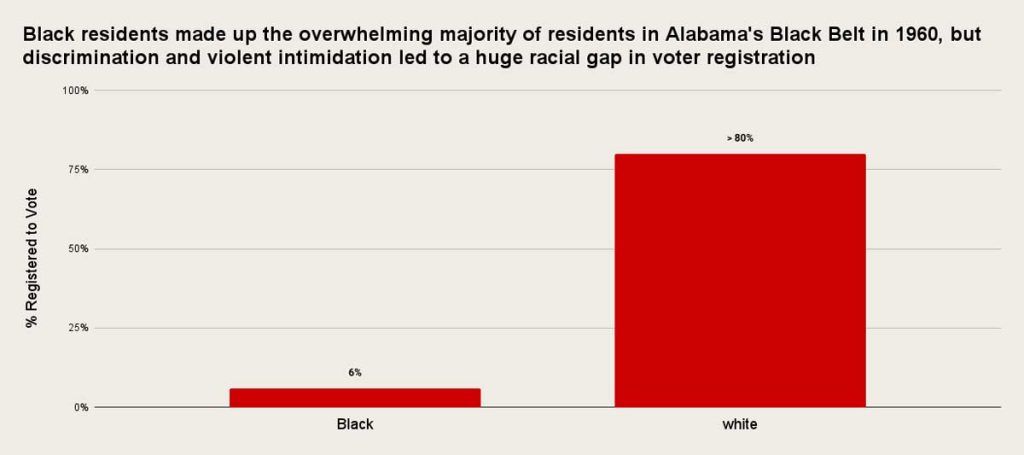

The effects of these restrictions were as enduring as they were dramatic. As late as 1965, only 7% of Mississippi’s eligible Black electorate was registered to vote.18 Richard K. Scher, Politics in the New South: Republicanism, Race, and Leadership in Twentieth Century (Routledge, 1997), 250. In 1960, 18 of Alabama’s Black Belt counties remained home to most of the state’s Black residents, reflecting the region’s history of plantation agriculture dependent on racialized enslavement and sharecropping. Black voter registration in Alabama’s Black Belt counties averaged less than 6% in 1960, compared to an average white voter registration rate well over 80%.19 “Alabama Black Belt Counties Registered Voters in 1960,” in Black Freedom Struggle in the 20th Century: Federal Government Records, “Black and White Voter Registrations Statistics and Voter Registration Programs” (Jan. 1, 1961 to Dec. 31, 1965 (Accession #: 001351-019-0492)). Found in: Civil Rights during the Kennedy Administration, 1961 – 1963, Part 2: The Papers of Burke Marshall, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights. In three Alabama counties where Black residents constituted a racial majority, the documented rate of Black voter registration was zero.20 According to “Alabama Black Belt Counties Registered Voters in 1960,” Lowndes County (5,122 Black residents over age 21) and Wilcox County (6,085 Black residents over age 21) each had zero Black registered voters in 1960, while white registration rates in those counties exceeded 100% (more registered white voters than documented white residents over age 21). In Bullock County, which had 4,450 Black residents over age 21, only five were registered to vote, constituting a rate of 0.1%. In contrast, 92.2% of Bullock County’s 2,387 white residents over age 21 were registered.

The historical failure to protect Black civil rights also impacted jury service. In 1880, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment barred racial discrimination in jury selection.21 Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880). Black people in the South were able to exercise this right of citizenship for a few decades, but political shifts soon left the legal mandate of race-blind jury selection with no enforcement. “Ultimately, the decision proved aspirational at best,” writes legal scholar Alexis Hoag, “as it did little to protect against the subsequent de facto exclusion of Black people from juries.”22 Alexis Hoag, “An Unbroken Thread: African American Exclusion from Jury Service, Past and Present,” Louisiana Law Review 81 (2020): 62.

In summer 1891 in Orange County, North Carolina, for example, when the local newspaper printed the names of jurors selected to serve in the upcoming term, the list included two men listed as “colored”: Ruffin Crisp and Lee Allison.23 Orange County (N.C.) Observer, June 6, 1891, 3. Within that same decade, political factions committed to white supremacy used racist rhetoric and violence to build political influence in the state. In 1898, the movement to restore white control in North Carolina was elected to a majority of seats in the state legislature—and, in the city of Wilmington, carried out a bloody massacre that repressed the Black vote with deadly violence.24 See Equal Justice Initiative, “The Wilmington Massacre of 1898,” Nov. 10, 2024; Equal Justice Initiative, “August 2, 1900: North Carolina Votes to Disenfranchise Black Residents,” accessed Feb. 7, 2025; Sue Sturgis, “Will North Carolina Strike Illegal Voter Literacy Test from its Constitution?,” Facing South, Mar. 26, 2013. Two years later, state lawmakers passed discriminatory literacy tests and other voter qualifications intended to create an all-white electorate and cement their control of government. “By the election of 1904, North Carolina had not just suppressed black voter turnout—it had eliminated it completely.”25 Sturgis, “North Carolina Voter Literacy Test.” This was a common story throughout the South in the decades after Reconstruction.

Jury summonses, regularly compiled using voter registration lists, reflected the same racial exclusion seen in the voting booth.

Just as Black communities came to expect little representation from elected officials who had no need to court their votes, they expected—and found—little justice in courts where trial by [white] jury simply reinforced the racism and subjugation of life under Jim Crow.

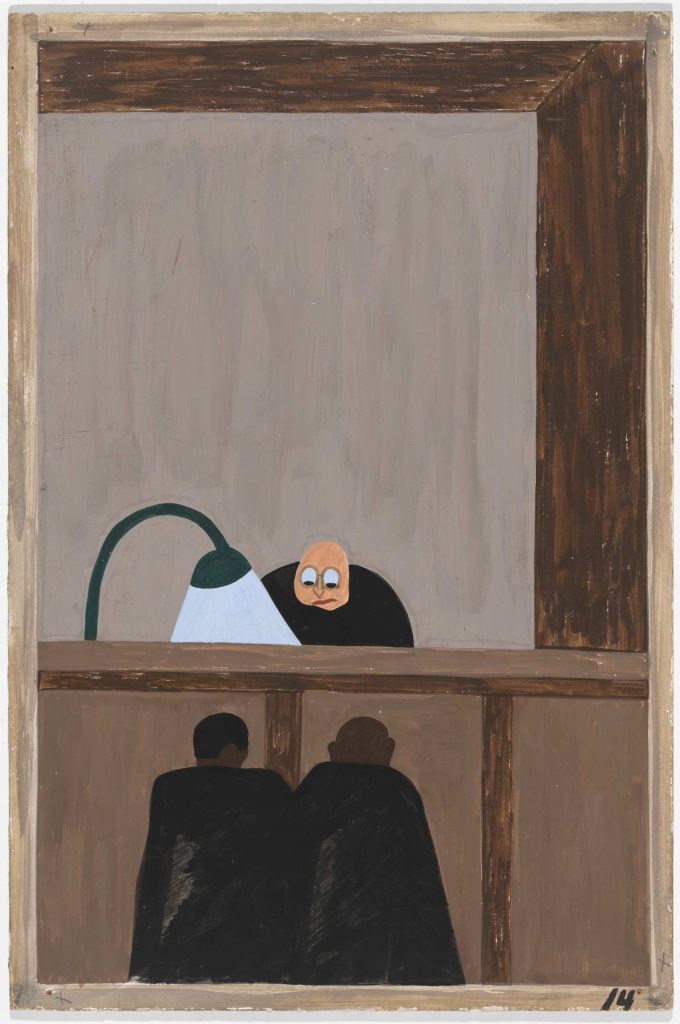

In 1941, Black visual artist Jacob Lawrence completed 60 painted panels that together narrated the Great Migration—a mass relocation of Black people from the American South to urban centers in the country’s North and West. Alongside images depicting the migration journey and the varied conditions that motivated it, the 14th panel of The Migration Series features a white judge sitting high atop his bench and leaning forward to peer down at two nondescript Black people shrouded in black and viewed from behind.

“Among the social conditions that existed which was partly the cause of the migration,” read Mr. Lawrence’s original caption, “was the injustice done to the Negroes in the courts.”26 Jacob Lawrence, “Panel 14,” The Migration Series, 1941. In 1993, Mr. Lawrence updated the Panel 14 caption to read, “For African Americans there was no justice in the southern courts.”

Historians and legal scholars have also recognized that, in the South, “justice” ignored Black victimization, brutally punished even the slightest allegation of Black criminality, and worked hand in hand with racial control’s most sinister tool: lynching.27 See Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (3d Ed. 2017) (“Southern lynching took on an even more racialized character after the Civil War. The act and threat of lynching became primarily a technique of enforcing racial exploitation—economic, political, and cultural.”).

Indeed, many of the era’s most infamous cases of unequal justice required the cooperation of all-white juries poised to punish any Black breach of the racial order—and willing to nullify charges brought against even the guiltiest of white defendants charged with harming Black people.

When nine innocent Black men and boys were accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931, the prosecution’s case was full of holes and their trials were repeatedly reversed due to racial bias. But those facts did nothing to discourage all-white juries from repeatedly convicting the defendants, nicknamed the Scottsboro Boys, and even sentencing some of them to death.28 See James Goodman, Stories of Scottsboro (Vintage Books, 1994); Stephen B. Bright, “Discrimination, Death and Denial: The Tolerance of Racial Discrimination in Infliction of the Death Penalty,” Santa Clara Law Review 35 (1995): 433, 440. In a much lesser-known case out of Thomasville, Georgia, in 1930, a Black man named Lacy Mitchell was lynched for testifying against a white man accused of raping a Black woman; the white defendant was then acquitted and released.29 “Maskers Slay Negro Witness,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 1, 1930; “Masked Band Kills Man Who Testified in Court,” Washington Post, Oct. 1, 1930; “Negro Witness Shot, Four White Men Held,” Atlanta Constitution, Sept. 29, 1930.

In Abbeville, Alabama, in 1944, a Black woman named Recy Taylor was kidnapped and gang-raped by a group of white men. Afterward, an all-white grand jury refused to indict anyone for Mrs. Taylor’s attack, even after one of the suspects confessed to police.30 Albert Deutsch, “Rape of Negress Ignored in South,” York (Pa.) Gazette and Daily, Dec. 8, 1944; see also Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance — A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (Knopf, 2010), xvii-xix.

And in September 1955, in majority-Black Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, an all-white jury acquitted two white men of killing 14-year-old Emmett Till.31 Hugh Stephen Whitaker, “A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Murder and Trial of Emmett Till,” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 8.2 (2005): 189-224. A few months later, for a $4,000 fee, both men gave a detailed magazine interview and confessed to killing the Black boy from Chicago for allegedly whistling at one of the white men’s wives.32 William Bradford Huie, “The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi,” Look Magazine, Jan. 24, 1956; Wicker Perlis, “Rediscovered Arrest Warrant Puts Emmett Till Killing Back in the Spotlight,” Clarion Ledger, July 1, 2022.

After both men died, the FBI re-opened its investigation into Emmett Till’s murder. In a 2006 report, the bureau diagnosed the cause of the unjust acquittal more than 50 years earlier:

“Negro Justice,” an unwritten, de facto, separate legal system, served as the foundation for jurisprudence between Blacks and whites … a system where the gravity of the crime was determined in large part by its impact on whites. The Black community had almost no recourse when … crimes [were] committed against Blacks by whites.33 Federal Bureau of Investigation, Prosecutive Report of Investigation Concerning Roy Bryant – Deceased; John William Milam, a.k.a. J.W. Milam – Deceased; Leslie F. Milam – Deceased; et. al. (Feb. 9, 2006), 8.