Reconstruction In America

Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876

Introduction

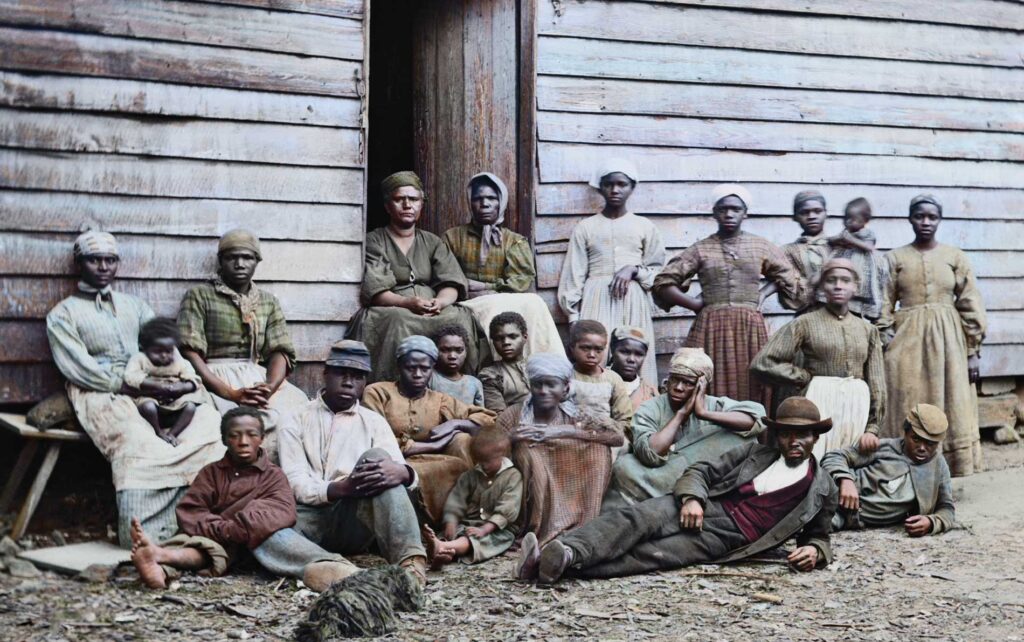

In 1865, after two and a half centuries of brutal enslavement, Black Americans had great hope that emancipation would finally mean real freedom and opportunity. Most formerly enslaved people in the United States were remarkably willing to live peacefully with those who had held them in bondage despite the violence they had suffered and the degradation they had endured.

Emancipated Black people put aside their enslavement and embraced education, hard work, faith, and citizenship with extraordinary enthusiasm and devotion. By 1868, over 80 percent of Black men who were eligible to vote had registered, schools for Black children became a priority, and courageous Black leaders overcame enormous obstacles to win elections to public office.

The new era of Reconstruction offered great promise and could have radically changed the history of this country. However, it quickly became clear that emancipation in the United States did not mean equality for Black people. The commitment to abolish chattel slavery was not accompanied by a commitment to equal rights or equal protection for African Americans and the hope of Reconstruction quickly became a nightmare of unparalleled violence and oppression.

Between 1865 and 1877, thousands of Black women, men, and children were killed, attacked, sexually assaulted, and terrorized by white mobs and individuals who were shielded from arrest and prosecution. White perpetrators of lawless, random violence against formerly enslaved people were almost never held accountable—instead, they frequently were celebrated. Emboldened Confederate veterans and former enslavers organized a reign of terror that effectively nullified constitutional amendments designed to provide Black people equal protection and the right to vote.

In a series of devastating decisions, the United States Supreme Court blocked Congressional efforts to protect formerly enslaved people. In decision after decision, the Court ceded control to the same white Southerners who used terror and violence to stop Black political participation, upheld laws and practices codifying racial hierarchy, and embraced a new constitutional order defined by “states’ rights.”

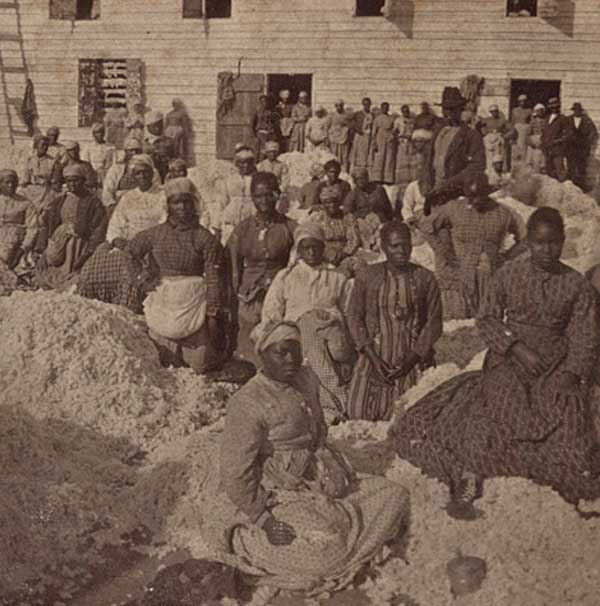

Within a decade after the Civil War, Congress began to abandon the promise of assistance to millions of formerly enslaved Black people. Violence, mass lynchings, and lawlessness enabled white Southerners to create a regime of white supremacy and Black disenfranchisement alongside a new economic order that continued to exploit Black labor. White officials in the North and West similarly rejected racial equality, codified racial discrimination, and occasionally embraced the same tactics of violent racial control seen in the South.

It was during Reconstruction that a century-long era of racial hierarchy, lynching, white supremacy, and bigotry was established—an era from which this nation has yet to recover.

Most Americans know very little about the Reconstruction era and its legacy. Historians have frequently overlooked this critical 12-year period that has had profound impact on life in the United States. Our collective ignorance of what happened immediately after the Civil War has contributed to misinformed stereotypes and misguided false narratives about who is honorable and who is not and has allowed bigotry and a legacy of racial injustice to persist.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative issued a new report that detailed over 4,400 documented racial terror lynchings of Black people in America between 1877 and 1950.

We now report that during the 12-year period of Reconstruction at least 2,000 Black women, men, and children were victims of racial terror lynchings.

Thousands more were assaulted, raped, or injured in racial terror attacks between 1865 and 1877. The rate of documented racial terror lynchings during Reconstruction is nearly three times greater than during the era we reported on in 2015. Dozens of mass lynchings took place during Reconstruction in communities across the country in which hundreds of Black people were killed.

Tragically, the rate of unknown lynchings of Black people during Reconstruction is also almost certainly dramatically higher than the thousands of unknown lynchings that took place between 1877 and 1950 for which no documentation can be found. The retaliatory killings of Black people by white Southerners immediately following the Civil War alone likely number in the thousands.

EJI presents this report to provide context and analysis of what happened during this tragic period of American history and to describe its implications for the issues we face today. We believe our nation has failed to adequately address or acknowledge our history of racial injustice and that we must commit to a new era of truth-telling followed by meaningful efforts to repair and remedy the continuing legacy of racial oppression. We hope this report sparks much needed conversation and encourages communities to join us in the important task of advancing truth and justice.

Bryan Stevenson, Director

Chapter 1

Journey to Freedom

Emancipation and Citizenship

“Just before the war, a white preacher, he come to us slaves and says: ‘Do you want to keep your homes where you get all to eat, and raise your children, or do you want to be free to roam around without a home, like the wild animals? If you want to keep your homes you better pray for the South to win. All that wants to pray for the South to win, raise your hand.’ We all raised our hands ‘cause we was scared not to, but we sho’ didn’t want the South to win.”1 “William M. Adams, Fort Worth, Texas.” Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 16, Texas, Part 1, Adams-Duhon. 1936.

Mr. William M. Adams

Formerly enslaved in Texas

In this Chapter

In this Chapter

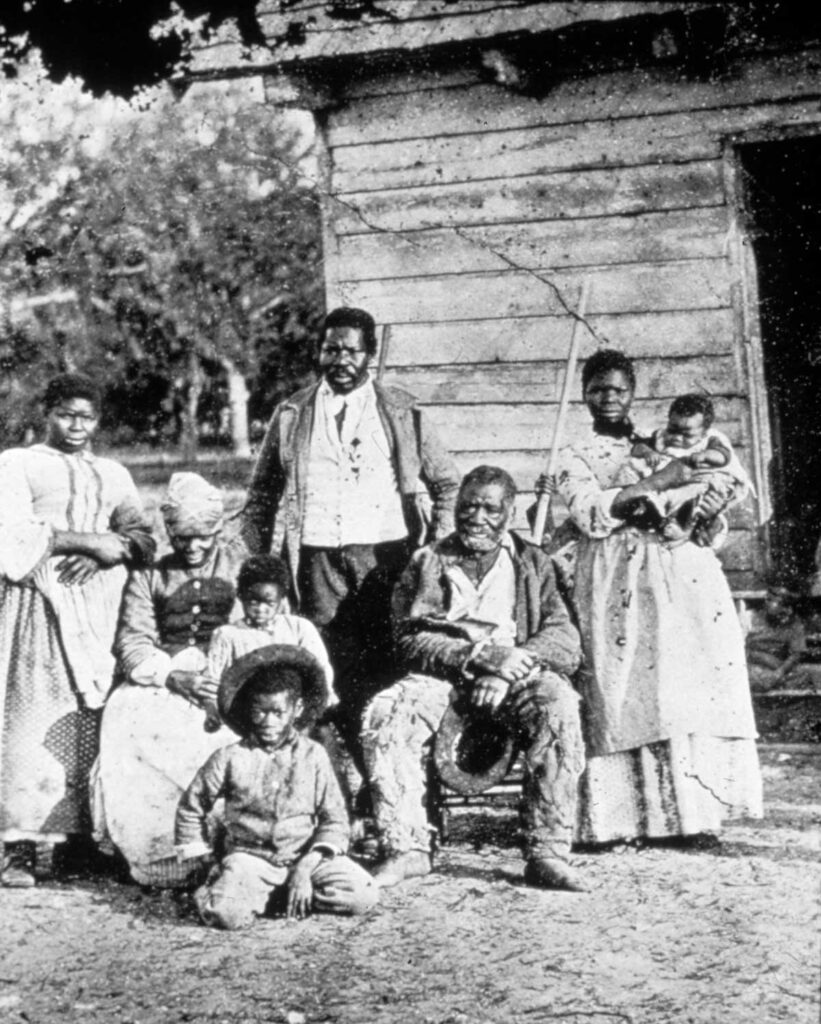

During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, an estimated 10.7 million African men, women, and children were kidnapped and sold into captivity in North America, South America, or Central America.2 David Eltis & Paul F. Lachance, Estimates of the Size and Direction of Transatlantic Slave Trade (2010). An estimated two million more people died during the brutal voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.3 Ibid. Though enslavement existed in other parts of the world, the unique system that developed in the United States became a racialized caste system rooted in a false but violent and persistent idea of racial difference.4 Frank Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas (New York: Vintage Books, 1947), 65. Chattel slavery in this country permanently deprived the enslaved of any legal rights or autonomy and permitted their violent economic exploitation.

Enslavement in the English colonies persisted after the Revolutionary War and the creation of the United States. Indeed, as the United States laid the foundation for its experiment in freedom and democracy, it also oversaw and benefitted from the kidnapping, human trafficking, lifelong bondage, and complete dehumanization of African people—a system of enslavement repeatedly enforced by the nation’s courts, political institutions, core documents, and most revered founders.

“I don’t believe in the colored race being slaves ‘cause of their color, but the war didn’t make time much better for a long time. Some of them had a worse time.”5 “Liney Chambers, Brinkley, Arkansas.” Federal Writer’s Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 2, Arkansas, Part 2, Cannon-Evans, 1936.

Ms. Liney Chambers

Formerly enslaved in Tennessee

In 1808, Congress banned the international slave trade and halted the trafficking of African people to the country6 Adam Rothman, “The Domestication of the Slave Trade in the United States,” in The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 40; Frederic Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press,

1996), 67. but did nothing to end enslavement within the nation’s borders. This resulted in a large unmet demand for enslaved Black people, especially in territories like Mississippi and Alabama that were gaining statehood and attracting white settlers with agricultural ambition.

The Domestic Slave Trade emerged to fill the void. The potential profit to be made from selling Black people already enslaved in the country skyrocketed. Though less well known than the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the domestic sale of enslaved Black people from the Upper and Eastern South resulted in the trafficking of millions—including many free Black people kidnapped and sold into enslavement7 See Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade (Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative, 2018), 39.—and fueled a massive increase in the Deep South’s enslaved population over the next 50 years.8 David L. Lightner, Slavery and the Commerce Power: How the Struggle Against the Interstate Slave Trade Led to the Civil War (Chelsea, MI: Sheridan Books, 2006), 6; Steven Deyle, “The Domestic Slave Trade in America: The Lifeblood of the Southern Slave System,” in The Chattel

Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 93; James Benson Sellers, Slavery in Alabama (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1950), 147.

In 1860, just a year before the start of the Civil War, enslavement was an entrenched and growing system, far from dying out or fading on its own.

Over four million Black people were enslaved in the United States—more than at any point in the nation’s history9 William C. Davis and William Marvel, National Park Civil War Series: A Concise History of the Civil War (Ft. Washington, Pennsylvania: Eastern National, 2007).—and unprecedented numbers of Black people in this country were trapped in brutal, inhumane conditions.10 Both the Southern and Northern economies remained tied to and dependent upon the labor of enslaved Black people, as Northern merchants traded in cotton and other agricultural products produced by enslaved people, and Northern banks accepted enslaved human “property” as collateral for securitized loans. See Sven Beckert, “Slavery and Capitalism,” Chron. of Higher Educ., December 12, 2014; see also Edward E. Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 2016). Even as growing political support for the abolition of slavery pushed the country closer to war, few white people who supported a legal end to the institution expressed a commitment to eradicating the harmful ideas of racial difference created to defend it.11 Davis and Marvel, A Concise History of the Civil War.

Inequality After Enslavement

On the question of racial equality, there was often little distinction between slavery’s white supporters and detractors. “God has made the negro an inferior being not in most cases, but in all cases,” leading pro-slavery New Yorker John H. Van Evrie wrote in the 1850s.12 Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From The Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Bold Type Books, 2016), 198. Even New England abolitionist Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe openly expressed the view that Black people were naturally inferior to white people. He tried to drum up support for abolition by assuring white people that Black people would “dwindle and gradually disappear from the peoples of this continent” if freed.13 Ibid. at 228. Clearly an end to enslavement alone would not emancipate Black people from racism. But first things would have to come first.

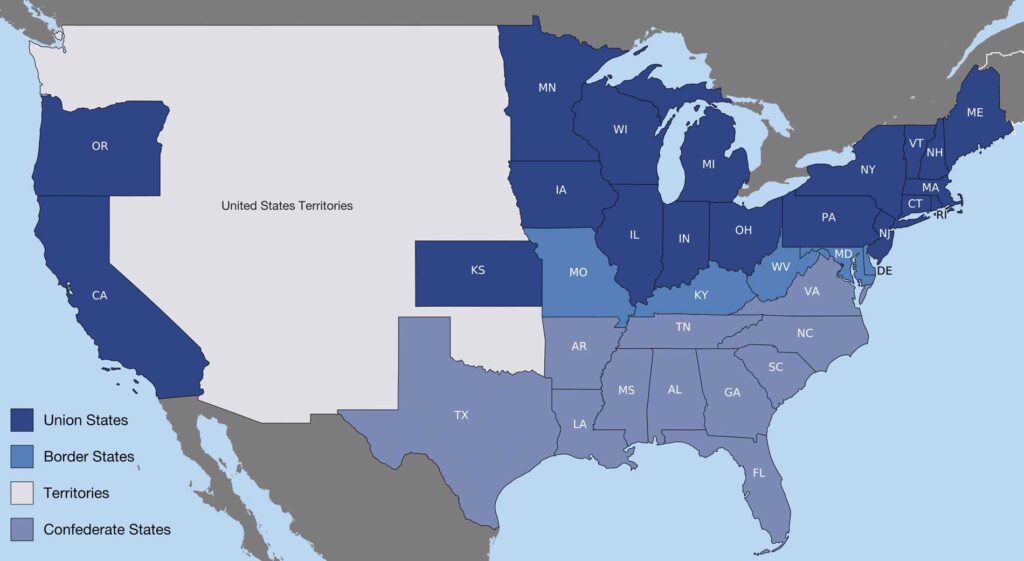

Beginning in 1861, 11 Southern states determined to maintain enslavement seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America.

In South Carolina, the first state to secede, legislators declared that “[a]n increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery” was a primary catalyst for their action.14 Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (Dec. 24, 1860). As Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee followed, the Confederacy developed a platform of “states’ rights” and “home rule” that aimed to preserve white supremacy and enslavement.

Even before the war’s end, Confederate hatred for Black autonomy and power led to brutal attacks. Black soldiers in the Union Army symbolized the height of Black “disobedience” and became immediate targets for violence that exceeded even the bounds of war.15 Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 182, 194-96.

When an outnumbered “colored” unit of the Union Army surrendered Fort Pillow, Tennessee, to Confederate forces on April 12, 1864, the rules of war required the Confederates to take the 262 Black soldiers as prisoners. Instead, the Confederates massacred the Black men, along with nearby Black civilians. A later federal investigation concluded: “It is the intention of the rebel authorities not to recognize the officers and men of our colored regiments as entitled to the treatment accorded by all civilized nations to prisoners of war.”

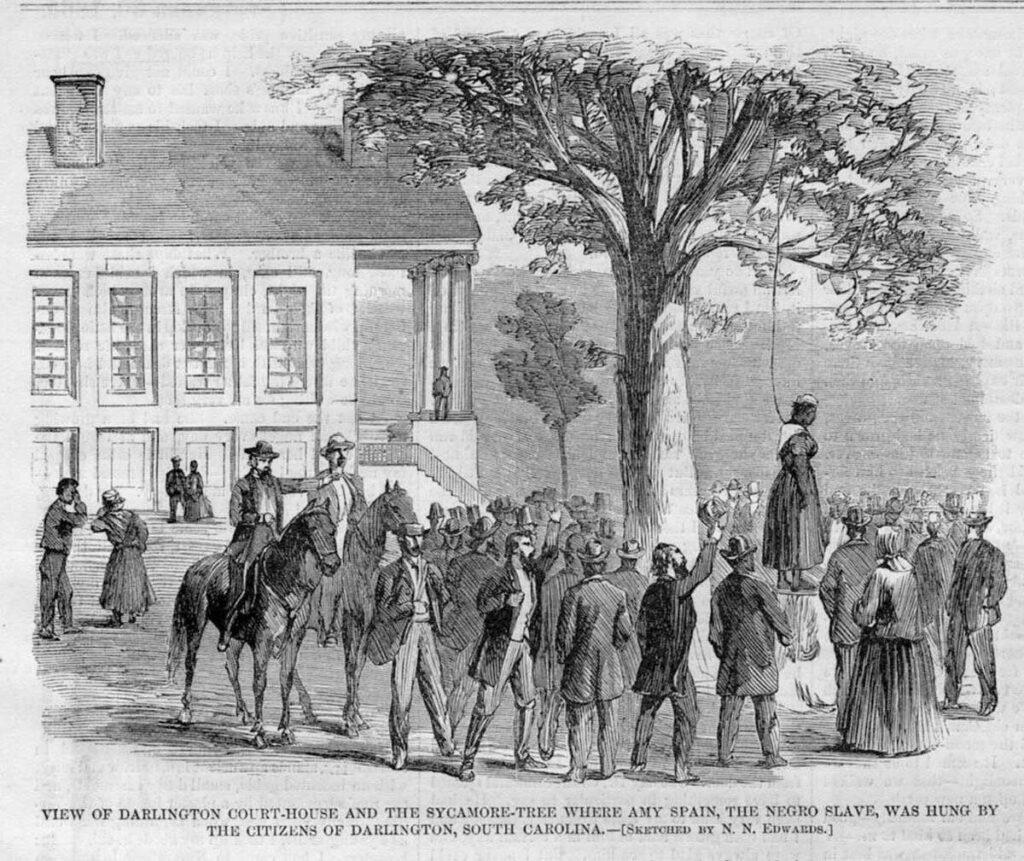

On March 10, 1865, Confederate soldiers in Darlington, South Carolina, hanged a young Black woman named Amy Spain from a sycamore tree on the courthouse lawn. Accused of “treason and conduct unbecoming a slave” for aiding Union forces who had briefly occupied the town, Ms. Spain was killed just weeks before the end of the Civil War.16 Harper’s Weekly, “The Hanging of Amy Spain,” September 30, 1865; The Woodstock Sentinel (Ill.), “Amy Spain,” October 11, 1865; Eugene Fallon, “A Day Darlington Would Like to Forget: Confederate Forces Hanged Amy Spain 94Years Ago,” The Augusta Chronicle-Herald (Ga.), May 10, 1959.

By the time the war ended with Confederate surrender to the Union on April 9, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln had issued an Emancipation Proclamation abolishing slavery in the rebel territories and Congress had advanced a constitutional amendment that aimed to abolish slavery nationwide. “Slavery is dead,” read an editorial in The Cincinnati Enquirer published days after the surrender. “The negro is not; there is our misfortune.”17 Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning, 13, 214.

If the end of the war led the United States government to abandon the millions of Black people still living in the war-torn South amidst a beaten Confederacy, those emancipated people’s futures in freedom would be bleak and short-lived. In a November 1865 letter to Major General Steadman of the Union Army, 125 freedmen in Columbus, Georgia, begged federal troops to stay in the city:

We wish to inform you that if the Federal Soldiers are withdrawn from us, we will be left in a most gloomy and helpless condition. A number of Freedmen have already been killed in this section of country; and . . . we have every reason to fear that others will share a similar fate.18 “Request of the Freedmen of Columbus, Ga. to Maj. Gen. Steadman not to withdraw the Federal Troops and leave them unprotected,” Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865 – 1869. M798 Roll 36.

Formerly enslaved Black people understood that federal intervention was necessary to require white Southerners to honor their rights as Americans. Their letter ended by pleading for federal troops “not to leave us to the tender mercy of our enemies—unprotected.”19 Ibid.

Decades later, in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois described the reality Black people faced. “Not a single Southern legislature stood ready to admit a Negro, under any conditions, to the polls,” he explained.

Not a single Southern legislature believed free Negro labor was possible without a system of restrictions that took all its freedom away; there was scarcely a white man in the South who did not honestly regard Emancipation as a crime, and its practical nullification as a duty.20 W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Atlantic, March 1, 1901.

After the Confederacy’s defeat, the United States was preserved but devastated, and faced an uncertain future. Many of the day’s most pressing questions asked: what would happen to the entrenched institution of slavery? And what fate would befall the millions of Black people who had been enslaved at the war’s start?

The 1863 Emancipation Proclamation left these questions unanswered. How the nation would travel from war to peace depended on how it would chart Black Americans’ path from slavery to freedom. Reconstruction became that path, but its initially hopeful promise proved to be short-lived, dangerous, and deadly.

Emancipation by Proclamation—Then by Law

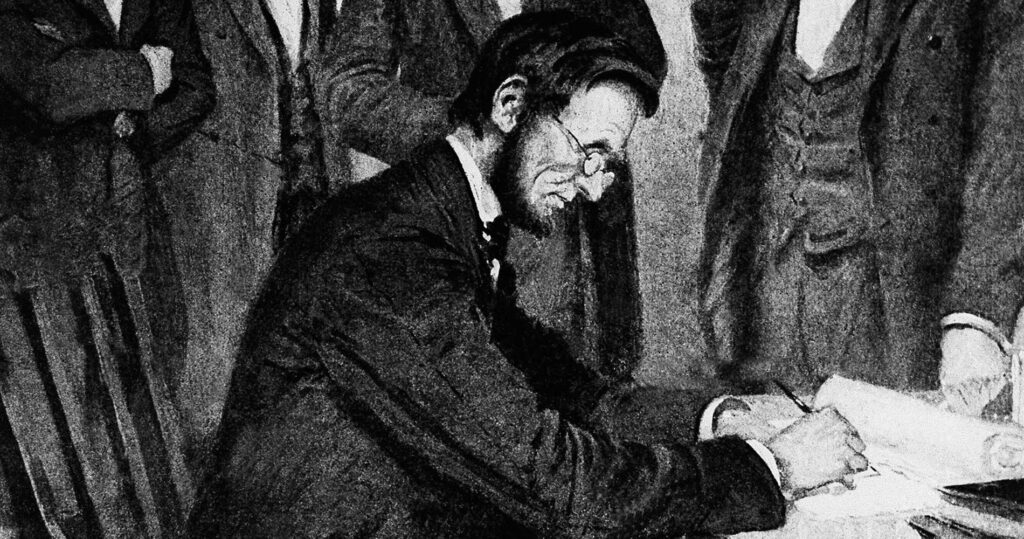

In September 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation announcing that, by executive order, he would declare the freedom of millions of Black people enslaved within the Confederacy—effective the following January. Enslavement was the core catalyst and conflict of the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation brought that conflict to a head.

For years before the Civil War, white people in the South had grown increasingly worried that federal authorities would try to force abolition upon the South, and increasingly certain that the resulting social and economic upheaval would destroy them all.

“Can [white people] without indignation and horror contemplate the triumph of negro equality, and see his own sons and daughters in the not distant future associating with free negroes upon terms of political and social equality?” Alabama official Stephen F. Hale asked in a 1860 letter to the governor of Kentucky.21 “Stephen F. Hale to Beriah Magoffin, December 27, 1860,” reproduced in full in Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Cause of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 91-103. If slavery was abolished, Hale warned, “the two races would be continually pressing together,” and an “amalgamation or the extermination of the one or the other would be inevitable.”22 Ibid.

That fear and anxiety largely fueled the Confederate states’ secession movement. After Alabama seceded from the Union a year later, Hale represented the state in the Confederate Congress as one of many voices in a pro-slavery chorus. Hale died from battle wounds in 1862,23 Encyclopedia of Alabama, “Stephen F. Hale.” months before Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation, but the Confederate reaction largely mirrored his views.

“They call Mr. Lincoln an ‘ape,’ a ‘fiend,’ a ‘beast,’ a ‘savage,’ a ‘highwayman,’” read an October 1862 issue of Harper’s Weekly, reporting on Southern reaction to Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation.

[The Confederate] Congress is resolved into a dozen committees, each trying to devise some new form of retaliation to be inflicted upon United States citizens and soldiers, if we dare to carry the proclamation into effect, and tamper—to use the words of the Richmond Enquirer—with “four thousand millions” worth of property!24 Harper’s Weekly, “The President’s Proclamation in Secessia,” October 18, 1862.

The Confederate Congress responded to the preliminary proclamation with a resolution denouncing Lincoln’s act as “a violation of the usages of civilized warfare, an attack on private property, and an invitation to servile insurrection” and vowing to resist enforcement.25 Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, Vol. II (Washington: Gov. Printing Office, 1904), 375-375, 393. But the proclamation did not enjoy uniform or widespread support in the North, either.

In the 1862 midterm elections, candidates challenging Lincoln’s political allies warned that Emancipation would bring an influx of free Black people into Northern states. “The general theme in the campaign, from New York to Iowa, was ‘Every white laboring man in the North who does not want to be swapped off for a free nigger should vote the [anti-Lincoln] Democratic ticket.’”26 Ibid. at 57. Indeed, many Northern states already had laws restricting emigration of free Black people, and had little more commitment to racial equality than their counterparts in the South. By the time election results were tallied, the anti-Emancipation message had won in Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania and vaulted Horatio Seymour—the fiercely pro-slavery “white man’s candidate’—to the governor’s office in New York.27 William Nester, The Age of Lincoln and the Art of American Power, 1848-1876 (Lincoln, Nebraska: Potomac Books, 2014), 169; Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, “Horatio Seymour,” October 8, 1869.

For all the opposition it inspired, the Emancipation Proclamation—more war measure than humanitarian act—stopped far short of ending slavery in the United States when it took effect on January 1, 1863.

On its face, the order declared the freedom of only those enslaved people held in states in rebellion against the United States, namely South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Texas, Arkansas, and North Carolina. The proclamation exempted Tennessee, as well as Union-occupied portions of Virginia and Louisiana, and left slavery wholly intact in the border states of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri.28 Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team Of Rivals: The Political Genius Of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 464.

Many Southern planters attempted to hide the news from enslaved people, using threats and violence to force silence and attacking those who dared attempt to flee.29 Ibid. at 182-83. Where federal troops were present, however, many enslaved people courageously fled bondage and sought protection and freedom in Union camps.30 See Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). For the many more enslaved people living where federal forces were absent or unreachable, Lincoln’s declaration did nothing, and the hold of enslavement lasted well beyond 1863.31 Litwack, Been In The Storm So Long, 172-74. Up until the war’s end in 1865, local newspapers in Montgomery, Alabama, continued to advertise auction sales of enslaved people and publish ads seeking the return of “runaways.”32 “Slave trading in Montgomery thrived well into the mid-1860s, even as the Civil War raged. As late as 1864, T.L. Frazer & Co. opened a new “slave market” in Montgomery on the south block of Market Street (present-day Dexter Avenue) between Lawrence and McDonough streets. In April 1864, a new firm of slave dealers announced plans to establish an office in Montgomery and promised to ‘‘keep constantly on hand a large and well selected stock such as families, house servants, gentlemens’ body servants, seamstresses, boys and girls of all descriptions, blacksmiths, field hands.” Tellingly, even after Robert E. Lee’s surrender, the Montgomery Daily Advertiser continued to run “reward” advertisements posted by slave owners seeking their runaway ‘property.’” Equal Justice Initiative, Slavery in America, 35.

In an August 1864 letter, a Black woman named Annie Davis living in Maryland asked Lincoln himself to clarify whether she remained in bondage. “Mr. President,” she began,

It is my Desire to be free. To go to see my people on the Eastern Shore. My mistress wont let me. You will please let me know if we are free and what I can do. I write to you for advice. Please send me word this week. or as soon as possible and oblidge [sic].33 “Annie Davis to Mr. President, 25 Aug. 1864,” D-304 1864, Letters Received, series 360, Colored Troops Division, Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 94, National Archives.

Ms. Davis’s letter survives at the National Archives among correspondence received by the Colored Troops Division. There is no evidence she ever received a reply.

If abolition was to become permanent and widespread, what began with the limited Emancipation Proclamation would have to become broader, national law. In December 1863, as the war continued and the Confederate states remained in rebellion, Congress proposed a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. It passed the Senate in April 1864 and, after extended debate and initial defeat, passed the House in January 1865. Ratification required approval by 27 of the 36 states, including in the South where states were still fighting a war to secede.

Within months, the Confederacy had surrendered, President Lincoln had been assassinated, and new federal laws required the rebel states to ratify the abolition amendment to be readmitted to the Union. The former Confederate states reluctantly complied. In early December 1865, Georgia became the 27th state to ratify, and the Thirteenth Amendment was adopted soon afterward. Several states nonetheless continued to resist ratification in symbolic defiance, even after legal abolition had been achieved—Delaware,34 Delaware ratified the Thirteenth Amendment in 1901. See Samuel B. Hoff, “Delaware’s Long Road to Ratification of the 13th Amendment,” Delaware Online, December 7, 2015. Kentucky,35 Kentucky ratified the Thirteenth Amendment in 1976. See The Indianapolis News, “Kentucky Ratifies 13th Amendment,” March 24, 1976. and Mississippi36 Mississippi did not officially ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until 1995, and did not formally file the ratification paperwork until February 7, 2013. See AP News, “130 Years After Civil War, Mississippi Senate Votes to Ban Slavery,” February 16, 1995; NPR.org, “After Snafu, Mississippi Ratifies Amendment Abolishing Slavery,” February 19, 2013. did not officially ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until the 20th century.

Perhaps more importantly, ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment did not reflect or require a commitment to racial equality or an agreement that enslavement should end.

The Thirteenth Amendment’s adoption meant that the Constitution banned racialized chattel slavery—it did not mean that white Southerners recognized Black people as fully human or that Southern officials would enforce their new legal protections absent federal oversight.

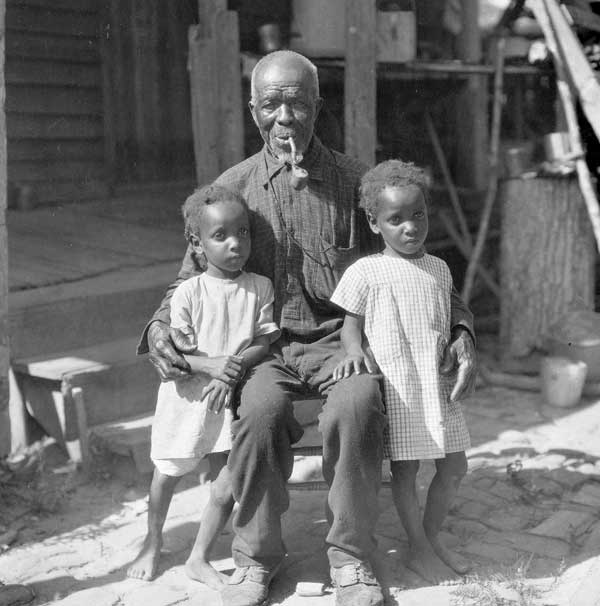

George King, a Black man in Oklahoma, recalled in 1937 how freedom was explained to him when he was emancipated in South Carolina decades earlier: “The Master he says we are all free,” Mr. King said, “but it don’t mean we is white. And it don’t mean we is equal.”37 “George King,” Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 13, Oklahoma, Adams-Young, 1936.

Following the war, Black autonomy expanded but the white American identity remained deeply rooted in white supremacy. Southern white communities rejected the notion that federal law recognized their former property as people, and they resented the Union troops still stationed in the region to enforce this new reality. This Southern white resistance to Black legal rights required the law to go further in order to make Black freedom truly meaningful.

The year after the war’s end, a U.S. Congress still operating without representation from most Confederate states passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, declaring Black Americans full citizens entitled to equal civil rights.38 Act of April 9, 1866 (Civil Rights Act), Public Law 39-26, 14 STAT 27, which protected all persons in the United States in their civil rights and furnished the means of their vindication.

President Andrew Johnson, who took office following Lincoln’s death, was a Tennessee native sympathetic to Southern sentiments. He vetoed the bill and vocally questioned “whether, where eleven of the thirty-six states are unrepresented in Congress at the time, it is sound policy to make our entire colored population, and all other excepted classes, citizens of the United States.”39 Andrew Johnson, “Veto of the Civil Rights Bill,” March 27, 1866. But Johnson also objected to the act’s substance:

The bill, in effect proposes a discrimination against large numbers of intelligent, worthy and patriotic foreigners and in favor of the negro, to whom, after long years of bondage, the avenues to freedom and intelligence have just now been suddenly opened. He must of necessity, from his previous unfortunate condition of servitude, be less informed as to the nature and character of our institutions than he who, coming from abroad, has to some extent, at least, familiarized himself with the principles of a Government to which he voluntarily entrusts life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.40 Ibid.

In April 1866, Congress—still celebrating the Union’s Civil War victory and persuaded by passionate rhetoric insisting rights legislation was needed to make that bloodshed meaningful—enacted the Civil Rights Act, overriding a presidential veto of a major piece of legislature for the first time in United States history.51 Foner, Reconstruction, 250-51.

Lawmakers next successfully passed the Fourteenth Amendment, which declared Black people’s citizenship and established the civil rights of all citizens. This proposal also found a foe in President Johnson. In his message to Congress announcing that the amendment had been sent to the states for consideration, Johnson questioned the legitimacy of the process and made clear his administration’s disapproval.

I deem it proper to observe that the steps taken by Secretary of State, as detailed in the accompanying report, are to be considered as purely ministerial, and in no sense whatever committing the Executive to an approval or a recommendation of the amendment to the State legislatures or to the people.52 A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Vol. 5 (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of National Literature, 1897), 3590.

Before the Fourteenth Amendment could become an enforceable part of the Constitution, 28 of the 37 states had to ratify it. Likely emboldened by Johnson’s defiant message of opposition, Southern legislatures refused—10 of the 11 former Confederate states rejected the amendment with overwhelming majorities and Louisiana did so unanimously.53 Foner, Reconstruction, 269. The amendment fell short of the required state ratifications and could not yet be adopted.

In response, and again over President Johnson’s veto, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, imposing military rule on the South and requiring states seeking readmission to the Union to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment.54 Ibid.

The Reconstruction Acts also established voting rights for African American men, dramatically altering the South’s political landscape. By July 1868, enough states had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment and it was adopted. The United States Constitution now declared all persons born in the country were citizens, regardless of race, and thus entitled to the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship, due process, and equal protection under the law.55 U.S. Const. amend. XIV. Two years later, in 1870, the United States ratified the Fifteenth Amendment, explicitly prohibiting racial discrimination in voting56 U.S. Const. amend. XV.—but leaving women of all races disenfranchised for another 50 years.57 The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified and adopted on August 18, 1920, established the voting rights of American women. In practice, the vast majority of Black men and women remained disenfranchised well into the 20th century due to racially-discriminatory state laws and policies in the South, and federal non-enforcement of the 15th Amendment. Black voting rights did not become widespread reality in America until, nearly a century after the 15th Amendment’s passage, and in response to mass movements led by a new generation of Black civil rights activists and organizers, Congress in 1965 passed the Voting Rights Act. See Henry Louis Gates Jr., Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy and the Rise of Jim Crow(New York: Penguin Press, 2019). Together, these legal developments established the meaning of citizenship for Black people who, just a few years earlier, had been denied that status by the nation’s highest court.

In Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857, the Supreme Court declared Black people born in the United States ineligible for national citizenship and unable to claim the rights and immunities guaranteed by the Constitution.

Now, little more than a decade later and following the national upheaval of civil war and political reconstruction, the nation for the first time beheld a new legal creation: the Black American. Throughout the country, Black men, women, and children—some of whom had been free for generations and others who were enslaved until very recently—were for the first time legally protected from racialized enslavement, recognized as United States citizens, and legally guaranteed the rights of that status.

Political participation, education, and economic advancement soon emerged as the immediate goals and most powerful symbols of freedom. Those also proved to be the earliest targets of overwhelming post-Emancipation racial violence.

Acknowledgments

This report is written, researched, designed, and produced by the Equal Justice Initiative. It is a part of a series of reports researched, written, and produced by EJI on the history of racial inequality in America. We would like to specially thank Jennifer Taylor for research, writing, editing, and photo research. Special thanks to Aaryn Urell for layout and editing; Kiara Boone for research, writing, and photo research; Jonathan Gibson for research, writing, photo research, photography, and data visualization; Adam Murphy, Sade Stevens, Kayla Vinson, Trey Walk, Sumita Rajpurohit, and Breana Lamkin for research and writing; John Dalton and Keiana West for editing; Gabrielle Daniels, Kari Nelson, Menna Elsayed, Jesse Chung, Alison Ganem, and Abigail Gellman for research; Jose Vazquez for photography and image research; Bryan G. Stevenson for photography; and Michaela Clark for photo research. We are also grateful to Josh Cannon, Elizabeth Woodson, Randy Susskind, Sonia Kapadia, and Emily Lumpkin for project support, production, and memorial assistance. We are also thankful to Jamiel Law, Matt Rota, and Dola Sun for illustrations.