Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

The enslavement of human beings occupies a painful and tragic space in world history. Denying a person freedom, autonomy, and life represents the worst kind of abuse of human rights.

Many societies tolerated and condoned human slavery for centuries. But in the 15th century, an expanded and terrifying new era of enslavement emerged that has had a profound and devastating impact on human history.

The abduction, abuse, and enslavement of Africans by Europeans for nearly five centuries dramatically altered the global landscape and created a legacy of suffering and bigotry that can still be seen today.

After discovering lands that had been occupied by Indigenous people for centuries, European powers sent ships and armed militia to exploit these new lands for wealth and profit starting in the 1400s. In territories we now call “the Americas,” gold, sugar, tobacco, and extraordinary natural resources were viewed as opportunities to gain power and influence for Portugal, Spain, Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, and Scandinavian nations.

Europeans first sought to enslave the Indigenous people who occupied these lands to create wealth for foreign powers, resulting in a catastrophic genocide. Disease, famine, and conflict killed millions of Native people within a relatively short period of time.

Determined to extract wealth from these distant lands, European powers sought labor from Africa, launching a tragic era of kidnapping, abduction, and trafficking that resulted in the enslavement of millions of African people.

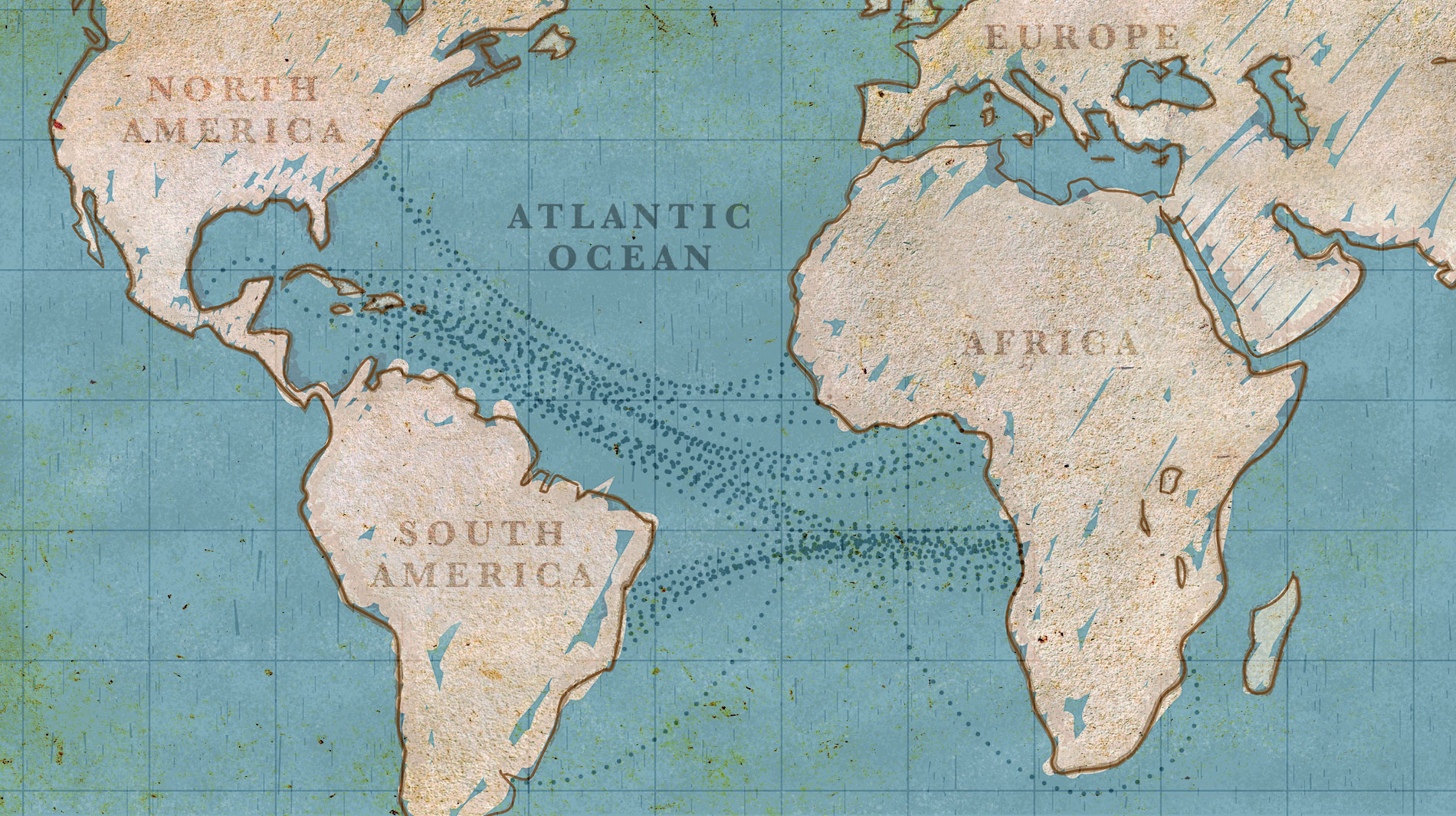

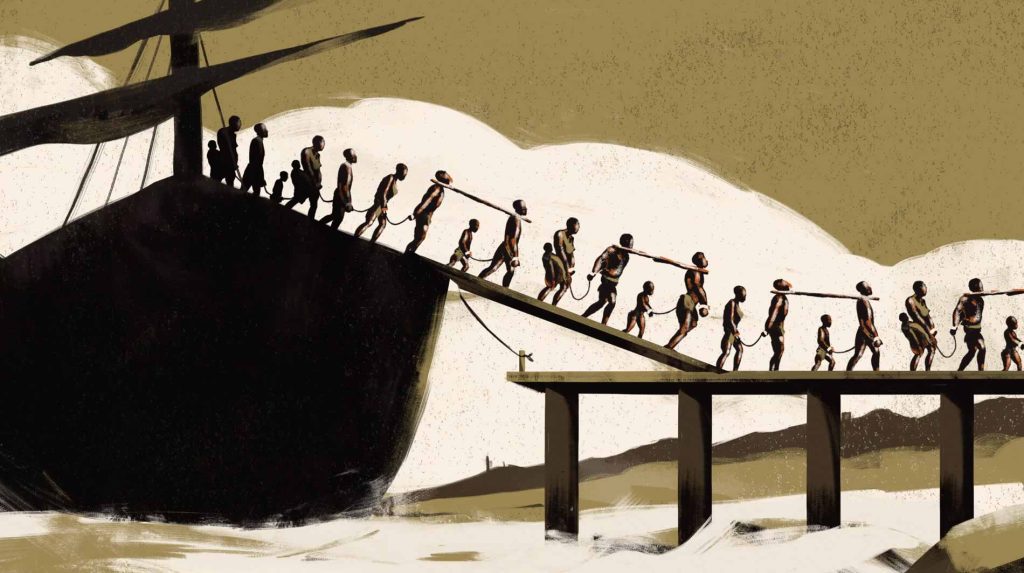

Between 1501 and 1867, nearly 13 million African people were kidnapped, forced onto European and American ships, and trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean to be enslaved, abused, and forever separated from their homes, families, ancestors, and cultures.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade represents one of the most violent, traumatizing, and horrific eras in world history. Nearly two million people died during the barbaric Middle Passage across the ocean. The African continent was left destabilized and vulnerable to conquest and violence for centuries. The Americas became a place where race and color created a caste system defined by inequality and abuse.

In the “colonies” that became the United States, slavery took on uniquely appalling features. From New England to Texas, Black people were dehumanized and abused while they were enslaved and denied basic freedoms. Legal and political systems were created to codify racial hierarchy and ensure white supremacy. Slavery became permanent and hereditary, defined by race-based ideologies that insisted on racial subordination of Black people for decades after the formal abolition of slavery.

Millions of Black people born in the U.S. were subjected to abuse, violence, and forced labor despite the young nation’s identity as a constitutional democracy founded on the belief that “all men are created equal.” Racialized slavery was ignored, defended, or accommodated by leaders while the new nation gained extraordinary wealth and influence in the global economy based on the forced labor of enslaved Black people.

The economic legacy of the Transatlantic Slave Trade—including generational wealth and the founding of industries that continue to thrive today—is not well understood.

New England, Boston, New York City, the Mid-Atlantic, Virginia, Richmond, the Carolinas, Charleston, Savannah, the Deep South, and New Orleans were shaped by the trafficking of African people, but few have acknowledged their history of enslavement or its legacy.

This report is a first step in helping people understand the scope and scale of the devastation created by slavery in America and the Transatlantic Slave Trade’s influence on a range of contemporary issues. It seeks to initiate more meaningful and truthful conversations about the history of slavery in America and how we can effectively address its legacy.

At a time when some believe we should avoid any discourse about our history that is uncomfortable, we believe that an honest engagement with our past is essential if we are to create a healthy and just future.

Bryan Stevenson, Executive Director

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Maya Angelou

Chapter 1

Origins

In this Chapter

In this Chapter

The enslavement of people has been a part of human history for centuries. Slavery and human bondage has taken many forms, including enslaving people as prisoners of war or due to their beliefs,1 See David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (Oxford University Press, 2006), 27, 32; Jack Goody, “Slavery in Time and Space,” in Asian and African Systems of Slavery, ed. James L. Watson (Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980), 25-27, 32-35. but the permanent, hereditary enslavement based on race later adopted in the U.S. was rare before the 15th century.

Many attributes of slavery began to change when European settlers intent on colonizing the Americas used violence and military power to compel forced labor from enslaved people. Indigenous people became the first victims of forced labor and enslavement at the hands of Europeans in the Americas. However, millions of Indigenous people died from disease, famine, war, and harsh labor conditions in the decades that followed.2 Russell Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 42-54.

Committed to extracting profit from their colonies in the Americas, European powers turned to the African continent. To meet their ever-growing need for labor, they initiated a massive global undertaking that relied on abduction, human trafficking, and racializing enslavement at a scale without precedent in human history. Never before had millions of people been kidnapped and trafficked over such a great distance.

The permanent displacement of 12.5 million African people to a foreign land, with no possibility of ever returning, created an enduring legacy and shaped challenges that remain with us today.3 David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), 23.

The European Influence on Africa

Europe had no contact with Sub-Saharan Africa before the Portuguese, seeking wealth and gold, sailed down the western coast of Africa and reached the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana) in 1471.4 Junius P. Rodriguez, ed., The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume I (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1997), 307-08. Initially focused on obtaining gold, Portugal established trading relationships and built El Mina Fort to protect its interests in the gold trade.5 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 89.

The convergence of European powers in Sub-Saharan Africa set in motion a devastating process that fused sophisticated labor exploitation, international commerce, mass enslavement, and an elaborate race-based ideology to create the Transatlantic Slave Trade.6 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 21, 99; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 81-82, 84, 87, 89, 109.

Over the following decades, the Spanish, English, French, Dutch, Danish, and Swedes began to make contact with Sub-Saharan Africa as well. Portugal soon converted El Mina into a prison for holding kidnapped Africans, and European traffickers built castles, barracoons, and forts on the African coast to support the forced enslavement of abducted Africans.

German and Italian merchants and bankers who did not personally traffic kidnapped Africans nonetheless provided essential funding and insurance to develop the Transatlantic Slave Trade and plantation economy.7 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 87-89 Italian merchants were essential in the effort to extend the sugar plantation system to the Atlantic Islands off the west coast of Africa, like São Tomé, and financial capital from Genoa was instrumental in expanding Portugal’s ability to traffic Africans.8 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 84-89, 104, 109.

By the 1600s, every major European power had established trading relationships with Sub-Saharan Africa and was participating in the transportation of kidnapped Africans to the Americas in some way. During this time period, several thousand Africans were kidnapped and trafficked to mainland Europe and the Americas, but the volume of human trafficking soon escalated to horrific proportions.9 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 21, 99; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 81-82, 84, 87, 89, 109.

Led again by the Portuguese, European powers began to occupy the Americas in the 1500s. In the 16th and 17th centuries, using land stolen from Indigenous populations in the Americas, Europeans established plantations that relied on enslaved labor to mass produce goods (primarily sugar cane) for trading and sale.10 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 81, 97. The cultivation of sugar for mass consumption became a driving force in the growing trafficking of human beings from Africa.11 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 103, 107-09.

Europeans initially relied on Indigenous people to supply this labor.12 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 95-100. But mass killings and disease decimated Indigenous populations in what historian David Brion Davis called “the greatest known population loss in human history.”13 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 98.

The Indigenous population in Mexico plummeted by nearly 90% in 75 years. In Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and Dominican Republic), the population of Arawak and Taino people fell from between 300,000 and 500,000 in 1492 to fewer than 500 people by 1542, just five decades later.14 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 98. Without Indigenous workers, plantation owners in the Americas grew desperate for a new source of exploited labor.15 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 95-102.

Driven by the desire for wealth, these European powers shifted from acquiring gold and other goods in Sub-Saharan Africa to trafficking in human beings. Over the following centuries, Europeans demanded that millions of Africans be trafficked to work on plantations and in other businesses in the Americas.16 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 99-102.

Slavery had existed in Africa prior to this point, but this new commodification of human beings by European powers was entirely unique and it drastically changed the African concept of enslavement.17 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 99-102.

Although some African officials and merchants acquired wealth through the export of millions of people, the Transatlantic Slave Trade devastated and de-stabilized societies and economies across Africa. The scale of disruption and violence contributed to long-term conflict and violence on the continent while European powers were able to amass massive financial benefits and global power from this dehumanizing trade.18 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 100.

The Iberian powers of Spain and Portugal and their colonies in Uruguay and Brazil were responsible for trafficking 99% of the nearly 630,000 kidnapped Africans trafficked from 1501 to 1625.19 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 23, tbl. 2. Over the next 240 years, England, France, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, the Baltic States, and their colonies joined the Iberians in actively trafficking Africans. Almost 12 million kidnapped Africans were trafficked from 1625 to 1867.20 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 23, tbl. 2. Ships from Portugal and its colony Brazil alone were responsible for trafficking 5,849,300 kidnapped Africans during this time period.21 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 23, tbl. 2.

Ships originating in Great Britain were responsible for trafficking more than a quarter of all people taken from Africa from 1501 to 1867.22 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 23, tbl. 2. From 1726 to 1800, British ships were the leading traffickers of kidnapped Africans, responsible for taking more than two million people from Africa.23 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 23, tbl. 2.

From 1626 to 1867, ships from North America were responsible for trafficking at least 305,000 captured people from Africa. In the two years before the U.S. legally ended the international slave trade in 1808, a quarter of all trafficked Africans were carried in ships that flew the U.S. flag.24 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 34. Rhode Island’s ports combined to organize voyages responsible for trafficking at least 111,000 kidnapped Africans, making it one of the 15 largest originating ports in the world.25 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 39.

The Barbarity of the Middle Passage

The horrific conditions of the Middle Passage meant that of more than 12.5 million Africans kidnapped and trafficked through the Transatlantic Slave Trade, only 10.7 million survived the journey.26 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 19.

Eighty percent of the people who embarked for the Americas between 1500 and 1820 were kidnapped Africans, who far outnumbered European immigrants.27 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, xvii.

Almost two million Africans died during the Middle Passage—nearly one million more than all of the Americans who have died in every war fought since 1775 combined.28 Department of Veteran’s Affairs, America’s Wars Fact Sheet, May 2021, https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf; Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, xvii, 18-19.

Numbers like this can help to quantify the scope of the harm, but they fail to detail the horrific and torturous experience of those who perished and the trauma that 10.7 million Africans who survived the weeks-long journey carried with them.

Some enslaved people were taken from the coast of West Africa and sold to European slave traders. For most captives the experience of Transatlantic trafficking began weeks, months, or even years before they ever saw the coast. Driven by the increasing external demand from white enslavers and traders, African kidnappers traveled inland and kidnapped people from their villages and towns. In the 18th century, 70% of Africans trafficked in the Transatlantic Slave Trade were free people who had been “snatched from their homes and communities.”29 Sowande M. Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 63. They were most often forced to walk, bound together in a coffle, for dozens or even hundreds of miles until they reached the coast.30 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 63, 136; Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 87.

At the coast, kidnapped Africans were forced into barracoons, slave pens, and dungeons within prison castles to await the ships that would take them across the Atlantic. Kidnapped Africans were forced to board slave trading ships that stayed docked—sometimes for months—until they had loaded enough human cargo to make the passage sufficiently profitable for the enslavers.31 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 67, 99-101; Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, xvii, 160; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 100. Records do not establish an exact death toll, but scholars estimate the mortality rate among those confined in barracoons and on board docked trading ships “equaled that of Europe’s fourteenth-century Black Death,” which claimed at least 40% of Europe’s population.32 Alice M. Phillips, ed., “The Black Death: The Plague, 1331-1770,” John Martin Rare Book Room, Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, University of Iowa, 2017, http://hosted.lib.uiowa.edu/histmed/plague/.

Countless Africans perished before they even began the Middle Passage.33 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, xvii; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 100.

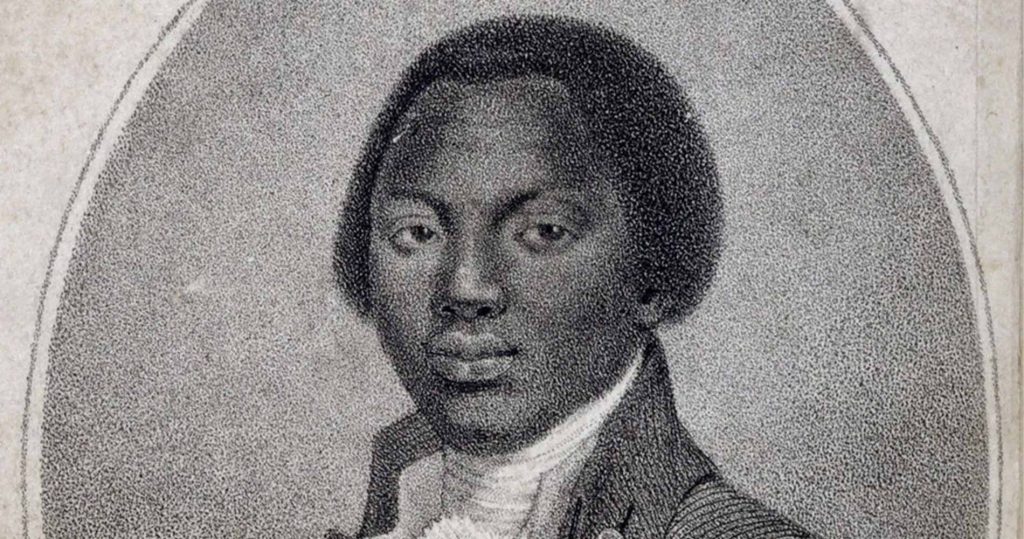

Ottobah Cugoano was a young child when he was “snatched away from [his] native country, with about eighteen or twenty more boys and girls.”34 Ottobah Cugoano, “Narrative of the Enslavement of Ottobah Cugoano, a Native of Africa; Published by Himself in the Year 1787,” in The Negro’s Memorial; or, Abolitionists Catechism; by an Abolitionist (London: Hatchard and Co., Piccadilly, and J. and A. Aroh, Conhill, 1825), 120. The kidnappers brandished “pistols and cutlasses” and threatened to kill the children if they did not come with them.35 Cugoano, “Narrative of Enslavement,” 121. For Ottobah and millions like him, the trauma of familial separation would be inflicted repeatedly in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Ottobah’s “hopes of returning home again were all over”36 Cugoano, “Narrative of Enslavement,” 122-23. as he was marched to the coast and placed in a prison until a white slave trader’s ship arrived three days later. “[I]t was a most horrible scene,” Ottobah later recounted. 37 Cugoano, “Narrative of Enslavement,” 124.

“[T]here was nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow-men. Some would not stir from the ground, when they were lashed and beat in the most horrible manner.”

Ottobah Cugoano

“Narrative of the Enslavement of Ottobah Cugoano,” 124.

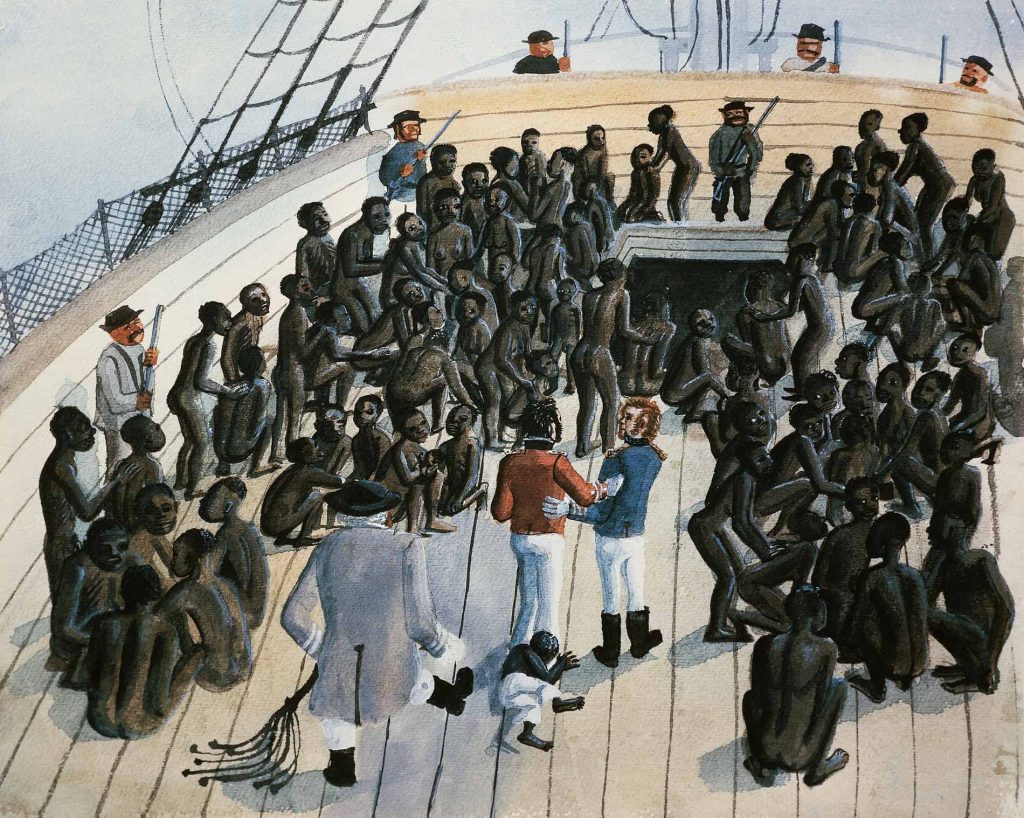

African captives were forced to undergo invasive and dehumanizing examinations before they boarded enslavers’ ships. Women, men, and children were stripped naked, prodded, and molested to determine if they were “prime slaves” capable of performing hard labor and having children.38 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 73-85.

Traders invasively groped the breasts, buttocks, and vaginal areas of women and young girls, allegedly to assess their childbearing ability.39 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 73-78, 85. Men and boys were similarly molested around the groin, scrotum, and anus.40 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 85. One white trafficker later testified the process was similar to what he would do to “a horse in this country, if I was about to purchase him.”41 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 85.

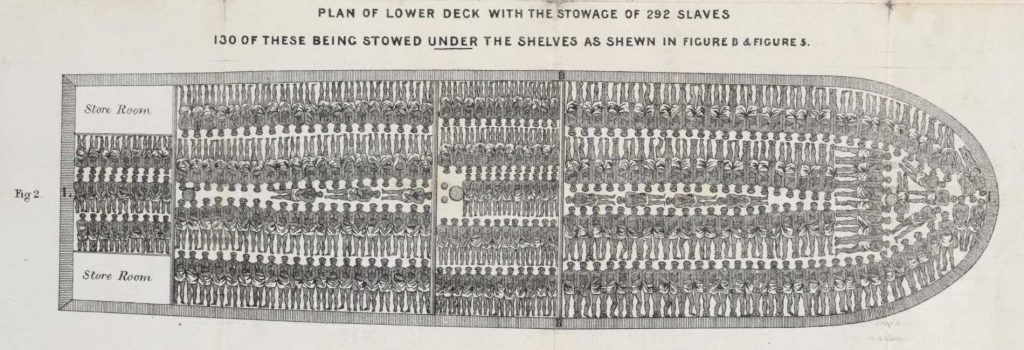

Captives were then assigned a number and loaded onto ships, separated by gender and tightly packed into the holds under conditions that were noxious and extreme. Men were typically “locked spoonways” together, naked and forced to lie in urine, feces, blood, and mucus, with little to no fresh air.42 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 105; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 92-93. Alexander Falconbridge, a white surgeon who participated in the slave trade, later testified that captives “had not so much room as a man in his coffin, neither in length or breadth, and it was impossible for them to turn or shift with any degree or ease.”43 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 105.

Trafficked Africans were forced to lie chained and manacled for weeks during the journey, unable to stretch out or stand except during limited time on deck. The foul conditions were a breeding ground for disease and vermin; some captives suffocated from the lack of air below deck.44 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 103-08; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 92-93. On some ships, the mortality rate was as high as 33%.45 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 92-93; Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 18-19.

About 15% of kidnapped Africans—nearly two million people—died during the Middle Passage.

African women and girls suffered similarly horrific conditions in the hold—and they were uniquely terrorized by the crew. Forced to be naked and segregated from the men, they lived in constant fear of being raped or assaulted by white sailors, who subjected them to sexual violence and flogged those who resisted.46 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 138-48; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 90-93.

Sexual assault of African women was so commonplace that Alexander Falconbridge later testified that sailors were “permitted to indulge their passions among them at pleasure.”47 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 138-44. Young girls were similarly subjected to violence. One surviving account details the experience of “a little girl of eight to ten years” who was repeatedly raped by a ship’s captain over three consecutive nights.48 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 144.

White sailors engaged in sexual violence without any fear of consequences or accountability.49 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 138-48; Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 90-93.

Some African women faced a second level of terror—the inability to protect their small children who were brought on board with them or born during the voyage.50 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 151-54. Many African women were forcibly separated from their infants when they were kidnapped from their homes or when they were sold to white traffickers but some women carried small infants with them. Babies were of little value in the market across the Atlantic, and so abusive sailors used them to manipulate, control, and terrorize their mothers.51 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 151-54. One account details a sailor who “tore the child from the mother, and threw it into the sea” when the newborn would not stop crying.52 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 151.

Another account from a white trafficker reports that a woman and her nine-month-old were purchased and placed onboard a ship. The baby “would not eat,” so the captain “flogged him with a cat o’ nine tails” in front of his mother and other captives on the ship.53 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 152-53. When he noticed that the baby’s feet were swollen, the captain ordered his crew to submerge the baby’s legs in boiling water, causing “the skin and nails [to come] off.”54 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 153. The baby still would not eat, so the captain flogged him at each meal time for several days before finally “[tying] a log of mango, either eighteen or twenty inches long, and about twelve or thirteen pound weight, to the child by a string round its neck,” beating the baby again, and dropping the baby to the ground, killing him.55 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 153. His mother—powerless to save her baby—was beaten until she agreed to throw her baby’s body overboard. This act of terror was intentionally committed in view of other captives to strike fear and maintain control.56 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 153-54.

Cruelty and terrorism were common on trafficking vessels operated by Europeans. Sailors inflicted brutal punishments for even minor offenses as a reminder of their control.57 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 131-37. One account from a white sailor reported that eight to 10 captives were brought to the top deck one night “for making a little noise in the rooms.”58 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 136-37. Sailors were then ordered to “tie them up to the booms [horizontal poles extending from the base of the mast], flog them very severely with a wire cat [a whip with multiple tails of wire], and afterwards clap the thumb-screws upon them, and leave them in that situation till morning.”59 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 136-37. The same sailor said the use of the thumb-screws—a device that crushed fingers via pressure—was so violent and harmful that it resulted in “fevers” and even death on occasion.60 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 136-37.

For more serious offenses, sailors inflicted even greater violence. One captive woman who was accused of aiding (but not actively participating) in an attempted revolt against the kidnappers, was strung up on the deck by her thumbs in view of the other captives. As a warning to them, she was flogged and knifed to death.61 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 158.

The threat of being flogged with a cat o’ nine tails [a multi-tailed whip with lashes often tipped with metal or barbs] or placed in the thumb-screws hung over each captive.62 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 186-87. Consuming more than their meager allotment of food could lead to whipping and torture.63 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 118-24. Captives were forced onto the deck and made to “dance” for exercise under threat of flogging. As one eyewitness observed, “Even those who had the flux, scurvy, and such edematous swelling in their legs, as made it painful to them to move at all, were compelled to dance by the cat.”64 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 92-93. Failure to eat one’s rations likewise resulted in abuse, whipping, or torture in the thumb-screws until the kidnapped African agreed to eat.65 Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea, 118-24, 186-87.

These excruciating conditions lasted for weeks and sometimes for months. A typical voyage took five or six weeks; some took two or three months.66 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 160. Longer voyages led to higher mortality rates among the kidnapped Africans on board.67 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 160.

When the ships landed in ports across North and South America, the kidnapped Africans who survived the Middle Passage were subjected to a renewed round of examinations and molestation by enslavers before they were sold again and forced to do hard labor that often resulted in their untimely deaths.68 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 92-93, 107-17; Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 6, 16, 159-61. Around 80% of kidnapped Africans transported across the Middle Passage were forced to work on sugar plantations under incredibly dangerous conditions that led to high mortality rates.69 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 6.

Slavery in the Americas

Of the enslaved men, women, and children who survived the Middle Passage, approximately 90% arrived in the Caribbean or South America.82 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, xix. The Portuguese, Spanish, French, British, and Dutch controlled slavery in the Americas, and each followed different political, legal, and cultural practices.83 Eltis and Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 21-23. Due in part to these differences, the evolution of slavery in the Americas varied across the region, as did the social construction of race and racial hierarchy.

There is no value in comparing the relative “harshness” of slavery across the Americas; the brutality and inhumanity of slavery was universal. Moreover, conditions in the South American and Caribbean colonies were horrific—the vast majority of enslaved people in these colonies worked on sugar plantations, which were notoriously harsh environments. Work on these plantations was “life-consuming,” with long hours of gang labor—often beginning at 5 a.m. and working until dusk—and extremely hazardous work conditions. Plantations in Brazil had higher mortality rates and lower life expectancies than plantations in the U.S.84 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 92-93, 107-119.

Factors specific to each European power and its colonies distinguished the experiences of enslaved men and women across the Americas. In the North American colonies and later the U.S., white people were in the majority everywhere except in South Carolina and Mississippi.85 Kathryn MacKay, “Statistics on Slavery,” Weber State University, accessed September 2, 2022, https://faculty.weber.edu/kmackay/statistics_on_slavery.htm. But in South America and the Caribbean, nonwhite people regularly exceeded 80% of the population.86 Steven Mintz, “Historical Context: American Slavery in Comparative Perspective,” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, accessed September 6, 2022, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teaching-resource/historical-context-american-slavery-comparative-perspective; Robert J. Cottrol, The Long Lingering Shadow: Law, Liberalism, and Cultures of Racial Hierarchy and Identity in the Americas (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013), 39.

When the Haitian revolution started in August 1791, white Europeans made up just 7% of the population and there were roughly as many free people of color as there were Europeans.87 Franklin W. Knight, “The Haitian Revolution,” American Historical Review 105, no. 1 (February 2000): 108. Iberian control in South America was challenged by the growing number of enslaved people, who often demanded their freedom in exchange for fighting Indigenous people who resisted European colonizers.88 Cottrol, Long Lingering Shadow, 34. In these colonies, the threat of rebellion against the minority white population was critical in shaping society.

In contrast, the exceptionally large white majority in North America meant that rebellions by enslaved people, while far more common than most people realize today, did not represent as great a threat to white rule.89 Cottrol, Long Lingering Shadow, 60, 86. As a result, while the fear of rebellions profoundly shaped the legal and cultural landscape of North America,90 See, e.g., Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013), 14, 18-21, 33 (discussing the impact of the Deslondes rebellion in Louisiana). British colonists rarely were forced to make legal or political concessions to enslaved people.

Geographic and demographic variations also distinguished how race and racial hierarchy developed in North America. For example, during the first century of Portuguese colonization in Brazil, there were very few Portuguese or white women,91 D. Wendy Greene, “Determining the (In)Determinable: Race in Brazil and the United States,” 14 Mich. J. Race & L. 143, 150 (2009). which meant that despite anti-miscegenation laws passed in Portugal, there were high rates of interracial sex between white men and women of African descent in Brazil.92 Greene, “Determining the (In)Determinable,” 150. By 1822, more than 70% of Brazil’s population “consisted of blacks or mulattoes, slaves, liberto, and free” people of color.93 Greene, “Determining the (In)Determinable,” 151.

Today, Brazil is home to the largest population of African descendants outside the African continent.94 Greene, “Determining the (In)Determinable,” 150.

In most South American and Caribbean colonies, large populations of free people of color emerged and “elaborate human taxonomies” based on race and caste were developed.95 Herbert S. Klein and Ben Vinson III, African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2d. ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 200-12. A different racial hierarchy evolved in North America, where free people of color represented a very small fraction of the population.96 Aaron O’Neill, “Black and Slave Population of the United States from 1790 to 1880,” Statista, June 21, 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1010169/black-and-slave-population-us-1790-1880/. There, a single, rigid color line separated two racial groups: Black and white.97 Klein and Vinson, African Slavery in Latin America, 195.

Finally, the legal codes that governed enslaved peoples’ lives—laws on manumission, the status of enslaved people as humans or property, marriage and family formation, and racial classification—varied by region and the colony.98 Klein and Vinson, African Slavery in Latin America, 207-14. These laws demonstrate the complex racial hierarchies in the region.

Throughout the region, racial discrimination was codified in laws that barred free Black people from “hold[ing] political office, practic[ing] prestigious professions (public notary, lawyer, surgeon, pharmacist, smelter) or enjoy[ing] equal social status with whites.”99 Ann Twinam, Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015), 52. But in 1795, the Spanish Crown made it possible to purchase whiteness—people of color with mixed ancestry could “apply and pay for a decree” that converted their legal status to white.100 Ann Twinam, “Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America,” Not Even Past, September 1, 2015, https://notevenpast.org/purchasing-whiteness-race-and-status-in-colonial-latin-america/. These laws sparked “vigorous and serious debate concerning the civil rights of those of mixed descent” in some countries. The 1812 constitution of the Spanish Empire further expanded opportunities for mixed-race citizens, including desegregating universities a century and a half before the U.S.101 Twinam, “Race and Status.”

In French colonies, the “Code Noir” passed by Louis XIV in 1685 shaped an entirely different landscape. The code mandated execution for an enslaved person who struck their enslaver,102 Article XXXIII, “The Code Noir (The Black Code),” LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, accessed October 17, 2022, https://revolution.chnm.org/d/335. but it also granted free people of color the same rights as any “persons born free,”103 Articles LVIII and LIX, “The Code Noir.” prohibited enslaved parents from being sold separately from their children,104 Article XLVII, “The Code Noir.” deemed free the child of a free woman and an enslaved man of color,105 Article XIII, “The Code Noir.” and fined an enslaver who had a child with an enslaved woman unless he married and freed the woman and her child.106 Article IX, “The Code Noir.”

Critically, under the Code Noir, free people of color dramatically increased their numbers. In Louisiana, which spent decades under French control, there were 18,647 free Black people by 1860—almost 3,000 more than in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi combined.107 Laura Foner, “The Free People of Color in Louisiana and St. Domingue: A Comparative Portrait of Two Three-Caste Slave Societies,” Journal of Social History 3, no. 4 (Summer 1970): 407 n.1 (citing U.S. Bureau of the Census, “Negro Population in the United States, 1790-1915” (Washington, 1918), 57).

The British and their descendants in North America made race the central aspect of laws governing slavery and the lives of enslaved and free Black Americans.108 Klein and Vinson, African Slavery in Latin America, 203 (“Especially following the Haitian Revolution, British, French, Dutch, and North American legislation became ever more hostile to freedmen.”). A stark “black-white binary” reflected and reinforced the centrality of race in all areas of American life.109 Klein and Vinson, African Slavery in Latin America, 201.

As a result, while the particular experience of slavery depended on region and time period, enslavement in the U.S. became a rigid, racialized caste system that inexorably tied enslavement to race.

The system of enslavement that emerged in North America was legitimated by an elaborate set of laws enforced through terror and violence and used to justify and codify the permanent, hereditary, and unending slavery of Black people for generations.

From the first arrival of kidnapped Africans in the English colonies that would become the United States, the institution of enslavement was foundational to the economy of every major city on the Eastern Seaboard. The history of these regions cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the role enslavement played in creating their economies, laws, and political and cultural institutions and the innumerable ways this legacy shapes these communities today.