Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

Beginning in the 16th century, millions of African people were kidnapped, enslaved, and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas under horrific conditions that frequently resulted in starvation and death. Nearly two million people died at sea during the agonizing journey. Over more than two centuries, the enslavement of Black people in the United States created wealth, opportunity, and prosperity for millions of Americans. As American slavery evolved, an elaborate and enduring mythology about the inferiority of Black people was created to legitimate, perpetuate, and defend slavery. This mythology survived slavery’s formal abolition following the Civil War.

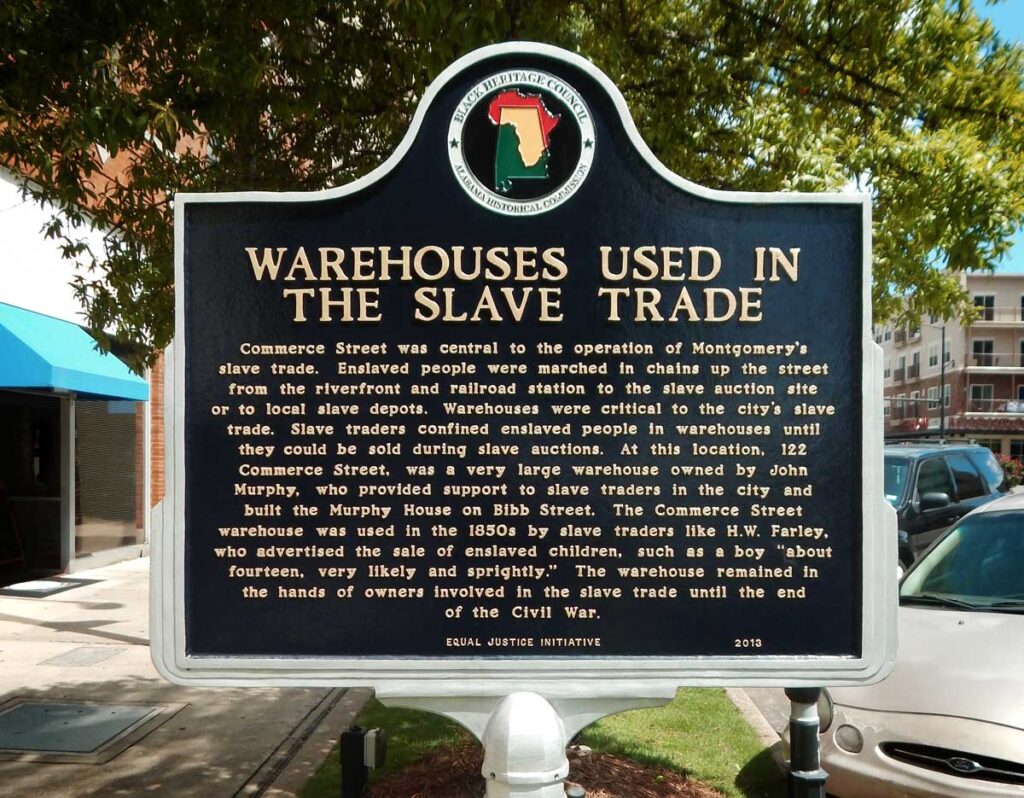

In the South, where the enslavement of Black people was widely embraced, resistance to ending slavery persisted for another century following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Today, more than 150 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, very little has been done to address the legacy of slavery and its meaning in contemporary life. In many communities like Montgomery, Alabama—which had a prominent role in the Domestic Slave Trade and was a primary site for human trafficking and facilitating slavery—there is little understanding of human trafficking, enslavement, or the longstanding effort to sustain the racial hierarchy that slavery created.

In fact, an alternative narrative has emerged in many Southern communities that celebrates the slavery era, honors slavery’s principal proponents and defenders, and refuses to acknowledge or address the problems created by the legacy of slavery. The enslavement of 10 million Black people had a profound impact on the legal, cultural, social, and economic character of the United States, but there is an absence of authentic and historically significant places in America that explore the lives of enslaved people and the history of slavery and its legacy.

We created three Legacy Sites in downtown Montgomery, Alabama, as sacred spaces for people to gather, learn, and reflect on this history. The Legacy Museum, located on the site of a cotton warehouse where enslaved people were forced to labor in bondage, tells the story of slavery in America and its legacy, using technology including holograms and videos that allow visitors to “listen” to the voices of enslaved people. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice features the names of more than 4,400 Black people killed in racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950. And on the banks of the Alabama River, near railroad tracks on which enslaved people were trafficked during the 19th century, Freedom Monument Sculpture Park is an exploration of the institution of slavery that is centered on the lives of enslaved people and designed to help people understand both the brutality of slavery and the humanity of the enslaved.

Reconciliation with a difficult past cannot be achieved without truthfully confronting history and finding a way forward that is thoughtful and responsible. We invite you to join us in this effort by exploring and sharing this report on American slavery, visiting the Legacy Sites in Montgomery, reflecting on the bonds between historic and contemporary racial inequality in America, and confronting the injustice in your own community. We hope that more information fosters greater knowledge and honest dialogue, and deepens our collective commitment to a just society. EJI believes that we have within us the capacity to transcend our history of racial injustice. But we shall overcome only if we engage in the important and difficult work that lies ahead.

Bryan Stevenson, Director

Chapter 1

Slavery in America

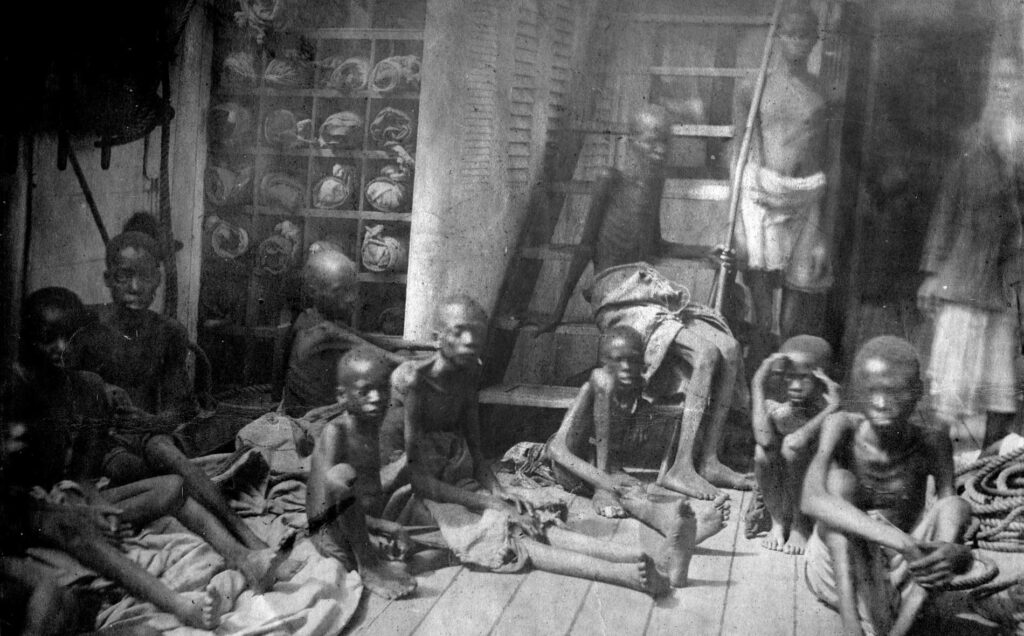

Nearly 13 million African people were kidnapped, forced onto European and American ships, and trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean to be enslaved, abused, and forever separated from their homes, families, ancestors, and cultures.

The enslavement of Black people in the United States lasted for more than two centuries and created a complex legal, economic, and social infrastructure that can still be seen today. The legacy of slavery has implications for many contemporary issues, political and social debates, and cultural norms—especially in places where enslavement or human trafficking was extensive.

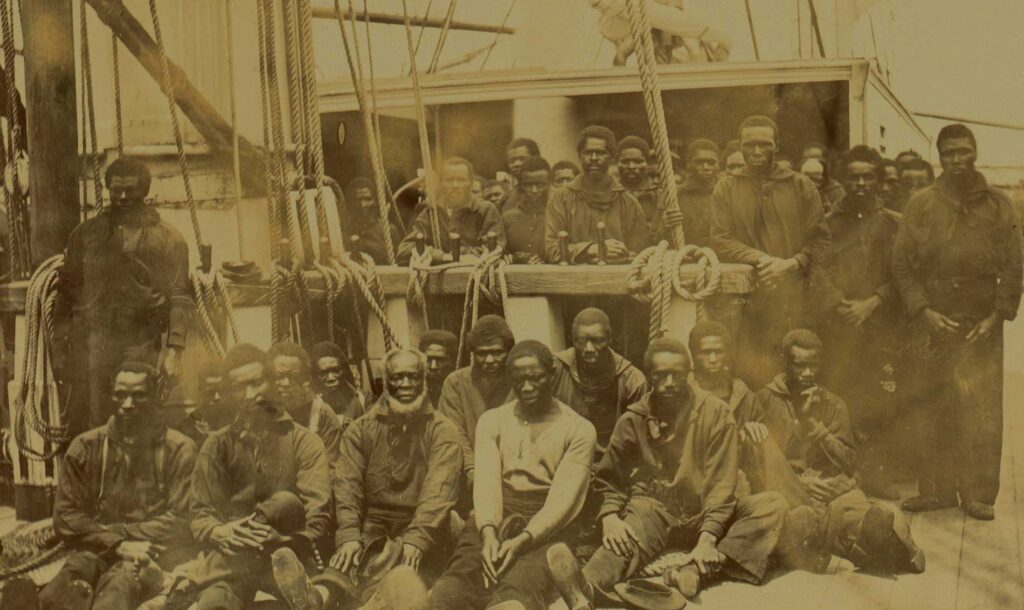

In the Transatlantic Slave Trade, kidnapped Africans were “bought” by traffickers from Western Europe in exchange for rum, cotton products, and weapons like guns and gunpowder.1 Transatlantic Slave Trade, UNESCO.org. As historian John Blassingame described, the captured Africans were then shipped across the Atlantic Ocean in cramped vessels under horrific conditions:

Taken on board ship, the naked Africans were shackled together on bare wooden boards in the hold, and packed so tightly that they could not sit upright. During the dreaded Mid-Passage (a trip of from three weeks to more than three months) . . . [t]he foul and poisonous air of the hold, extreme heat, men lying for hours in their own defecation, with blood and mucus covering the floor, caused a great deal of sickness. Mortality from undernourishment and disease was about 16 percent. The first few weeks of the trip was the most traumatic experience for the Africans. A number of them went insane and many became so despondent that they gave up the will to live. . . . Often they committed suicide, by drowning or refusing food or medicine, rather than accept their enslavement.2 John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 7.

Nearly 13 million African men, women, and children were kidnapped, forced onto European and American ships, and trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean to South America, Central America, or North America.3 David Eltis & Paul F. Lachance, Estimates of the Size and Direction of Transatlantic Slave Trade (2010). Nearly two million people perished during the brutal voyage.4 Ibid.

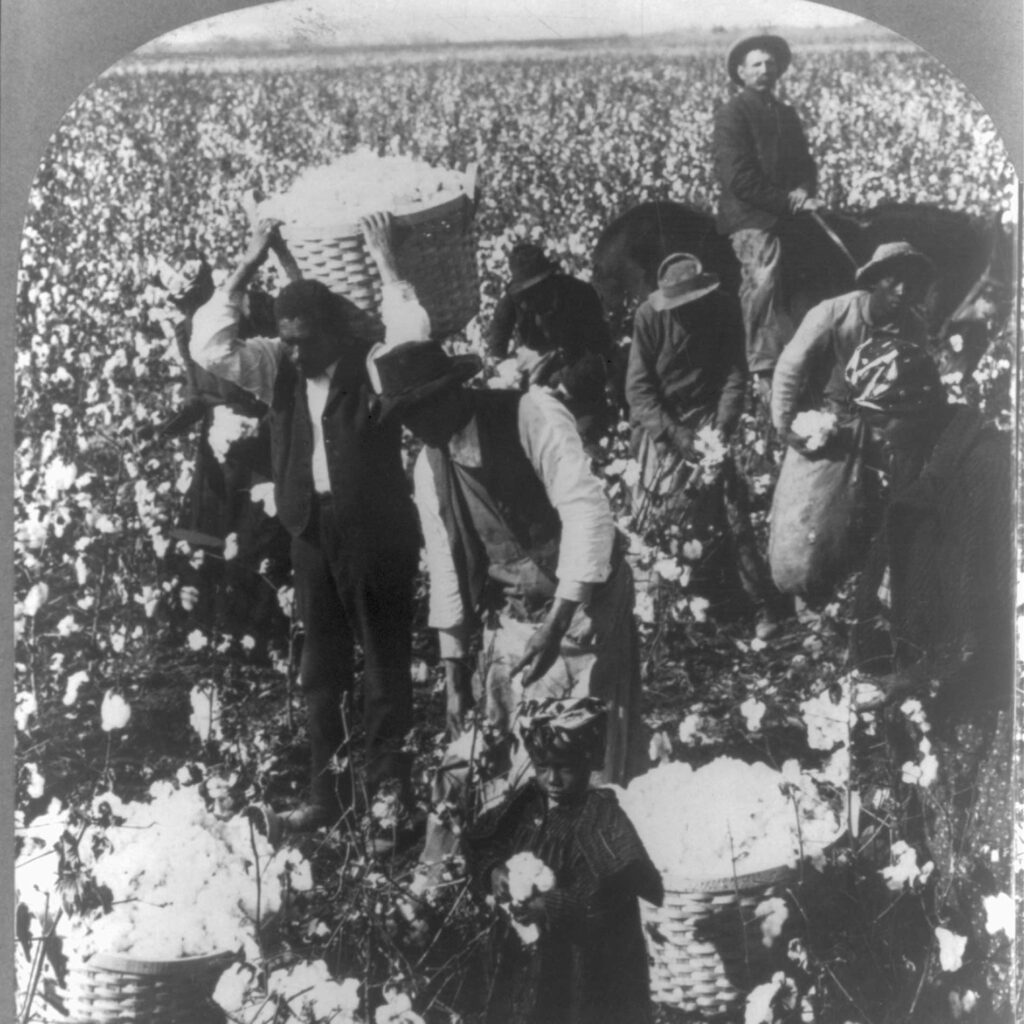

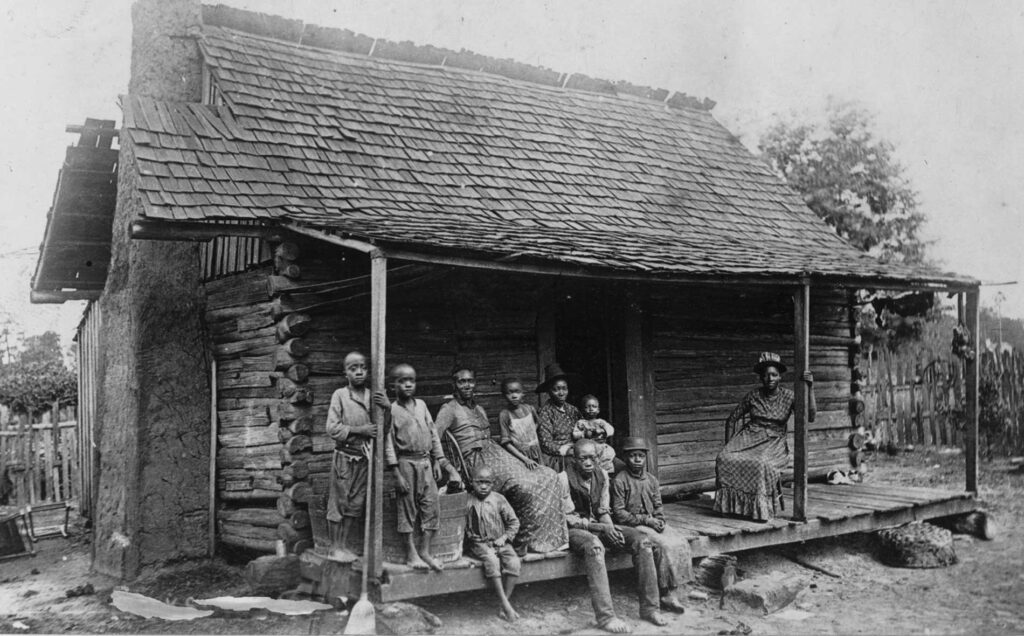

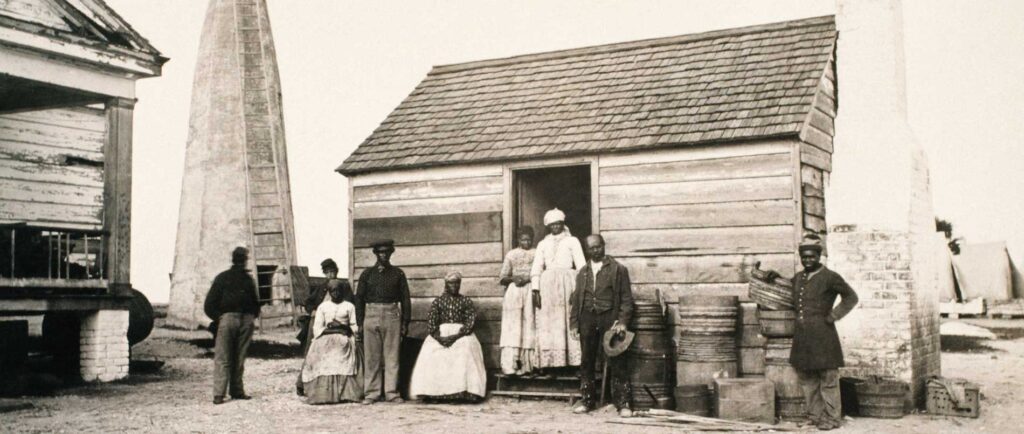

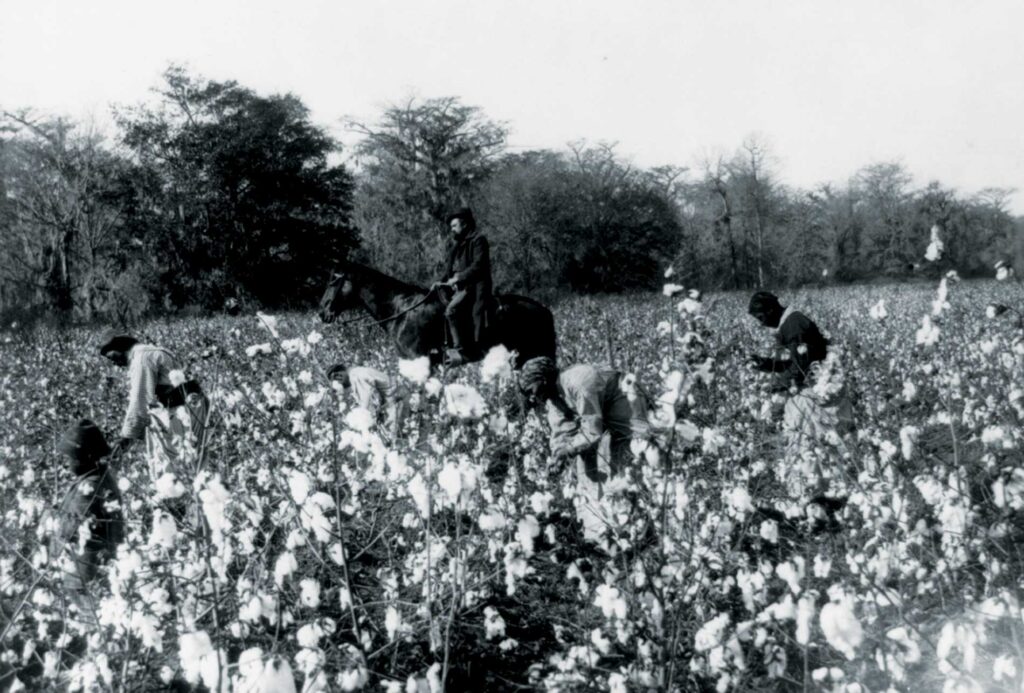

For the millions of Africans who would face enslavement in the United States—at the end of a transatlantic journey from Africa or from birth as the descendants of Africans transported to the country in bondage—the particular experience of American slavery took different forms based on region and time period. Those enslaved in the northeastern states were not as confined to agricultural work as those in the South and many spent their lives in bondage laboring as house servants or in various positions of unpaid, skilled labor.5 Slaves in New England, Medford Historical Society. The less diverse Southern economy, primarily centered around cotton and tobacco crops, gave rise to large plantations dependent on the labor of enslaved Africans, who toiled in the fields and ran the enslavers’ homes.6 Blassingame, The Slave Community, 249-83.

In many states where slavery was prevalent, most white people rejected emancipation and used violence, terror, and the law to disenfranchise, abuse, and marginalize Black Americans for more than a century.

Largely for this reason, slavery in the two regions diverged. Slavery became less efficient and less socially accepted in the Northeast during the 18th century, and those states began passing laws to gradually abolish slavery. In 1804, New Jersey became the last Northern state to commit to abolition. In contrast, the system of slavery remained a central and necessary ingredient in the Southern plantation economy and cultural landscape well into the 19th century.7 There were strenuous arguments in favor of increasing enslaved populations in the South in order to meet the “absolute necessity” of increasing the region’s labor supply in the face of growing demand for cotton. See, e.g., DeBow’s Review, “The South Demands More Negro Labor,” November 1858). By 1860, in the 15 Southern states that still permitted slavery, nearly one in four families owned enslaved people.8 U.S. Census Bureau, “Census of Population & Housing, 1860.” The South so desperately clung to the institution of slavery that, as the national tide turned toward abolition, 11 Southern states seceded from the United States, formed the Confederate States of America, and sparked a bloody civil war.

In December 1865, just eight months after Confederate forces surrendered and the four-year Civil War ended, the United States adopted the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as punishment for crime.” This meant freedom for more than four million enslaved Black people living in the United States at the time. However, in many states where slavery was prevalent, most white residents rejected emancipation and used violence, terror, and the law to disenfranchise, abuse, and marginalize Black Americans for more than a century after emancipation.

Inventing Racial Inferiority: How American Slavery Was Different

The racialized caste system of American slavery that originated in the British colonies was unique in many respects from the forms of slavery that existed in other parts of the world.9 For example, in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of South America, freed Black people did not retain a stigma of inferiority after slavery ended there the way they did in the United States. Frank Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas (New York: Vintage Books, 1947), 65. In the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, for example, slavery was a class category or form of indentured servitude, an “accident” of individual status that could befall anyone and could be overcome after a completed term of labor or assimilation into the dominant culture.10 Roman law, which remained influential in countries like Spain and Portugal in the 17th and 18th centuries, viewed slavery as a mere accident, of which anyone could be the victim. As such it tended to forestall the identification of the Black man with slavery “thus permitting the Negro to escape from the stigma of his degraded status once he ceased to be a slave.” Carl Degler, “Slavery and the Genesis of American Race Prejudice,” Comp. Stud. in Soc’y & Hist. (Oct. 1959): 50. “Yet, of course, ancient [Roman] slavery was fundamentally different from modern [American] slavery in being an equal opportunity condition—all ethnicities could be slaves—and in seeing slaves as primarily a social, not an economic, category.” Phillip D. Morgan, “Origins of American Slavery,” OAH Mag. of Hist. (July 2005): 51.

American slavery began as such a system. When the first Africans were brought to the British colonies in 1619 on a ship that docked in Jamestown, Virginia, they held the legal status of “servant.”11 “The status of the Negroes was that of servants, and so they were identified and treated down to the 1660s.” Oscar & Mary Handlin, “The Origins of the Southern Labor System,” William & Mary Q.(Apr. 1950): 203. But as the region’s economic system became increasingly dependent on forced labor, and as racial prejudice became more ingrained in the social culture, the institution of American slavery developed as a permanent, hereditary status centrally tied to race.12 “Slavery was not an isolated economic or institutional phenomenon; it was the practical facet of a general debasement, without which slavery could have no rationality. (Prejudice, too, was a form of debasement, a kind of slavery in the mind.) Certainly the urgent need for labor in a virgin country guided the direction which debasement took, molded it, in fact, into an institutional framework. That economic practicalities shaped the external form of debasement should not tempt one to forget, however, that slavery was at bottom a social arrangement, a way of society’s ordering its members in its own mind.” Winthrop D. Jordan, “Modern Tensions and the Origins of American Slavery,” J. of S. Hist. (Feb. 1962): 30. “[S]lavery became indelibly linked with people of African descent in the Western hemisphere. The dishonor, humiliation, and bestialization that were universally associated with chattel slavery merged with Blackness in the New World. The racial factor became one of the most distinctive features of slavery in the New World.” Morgan, “Origins of American Slavery,” 53.

The institution of American slavery developed as a permanent, hereditary status centrally tied to race.

Over the next 240 years, the system of American slavery grew from and reinforced racial prejudice.13 “[A]s slavery evolved as a legal status [in America], it reflected and included as a part of its essence, this same discrimination which white men had practiced against the Negro all along and before any statutes decreed it . . . . As a result, slavery, when it developed in the English colonies, could not help but be infused with the social attitude which had prevailed from the beginning, namely, that Negroes were inferior.” Degler, “Slavery and the Genesis of American Race Prejudice,” 52. Advocates of slavery argued that science and religion proved white racial superiority: under this view, white people were smart, hard-working, and more intellectually and morally evolved, while Black people were dumb, lazy, child-like, and in need of guidance and supervision. In 1857, for example, Mississippi Governor William McWillie denounced anti-slavery critics and insisted:

[T]he institution of slavery, per se, is as justifiable as the relation of husband and wife, parent and child, or any other civil institution of the State, and is most necessary to the well-being of the negro, being the only form of government or pupilage which can raise him from barbarism, or make him useful to himself or others; and I have no doubt but that the institution, thus far in our country, has resulted in the happiness and elevation of both races; that is, the negro and the white man. In no period of the world’s history have three millions of the negro race been so elevated in the scale of being, or so much civilized or Christianized, as those in the United States, as slaves. They are better clothed, better fed, better housed, and more cared for in sickness and in health, than has ever fallen to the lot of any similar number of the negro race in any age or nation; and as a Christian people, I feel that it is the duty of the South to keep them in their present position, at any cost and at every peril, even independently of the questions of interest and security.14 The Liberator, “Extracts from the Message of Gov. McWillie, of Mississippi, to the Legislature of the State,” December 11, 1857.

Though the reality of American slavery was often brutal, barbaric, and violent, the myth of Black people’s racial inferiority developed and persisted as a common justification for the system’s continuation.

This perspective defended Black people’s lifelong and nearly inescapable enslavement in the United States as justified and necessary. White enslavers were performing an act of kindness, advocates claimed, by exposing the Black people they held as human property to discipline, hard work, and morality. Though the reality of American slavery was often brutal, barbaric, and violent, the myth of Black people’s racial inferiority developed and persisted as a common justification for the system’s continuation. This remained true throughout the Civil War, the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, and the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Indeed, ending slavery was not enough to overcome the harmful ideas created to defend it.15 French researcher Alexis De Tocqueville observed that slavery was on a decline in some regions of the United States, but “the prejudice to which it has given birth is immovable.” Alexis De Tocqueville, Democracy in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002): 328-29. Writing more than a century later, American historian Carl Degler noted that “it is patent to anyone conversant with the nature of American slavery, particularly as it functioned in the nineteenth century, that the impress of bondage upon the character and future of the Negro in the United States has been both deep and enduring.” Degler, “Slavery and the Genesis of American Race Prejudice,” 49. “Freeing” the nation’s masses of enslaved Black people without undertaking the work to deconstruct the narrative of inferiority doomed those freedmen and -women and their descendants to a fate of subordinate, second-class citizenship. In the place of slavery, the commitment to racial hierarchy was expressed in many new forms, including lynching and other methods of racial terrorism; segregation and “Jim Crow”; and unprecedented rates of mass incarceration.

The Lives and Fears of America’s Enslaved People

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, confronted with abolitionists’ moral outrage and growing political pressure, Southern enslavers defended slavery as a benevolent system that benefitted enslaved Black people.21 Supra note 14. See also The Liberator, “Extracts from the Message of Gov. Winston, of Alabama, to the Legislature of the State,” December 11, 1857; Daniel Pratt, “To the Editor of the Journal,” Daily Alabama Journal, October 21, 1850. Even today, some continue to echo those claims in attempts to justify more than two centuries of human bondage, forced labor, and abuse.22 For example, Alabama state legislator Charles Davidson wrote a speech praising slavery for its civilizing influence on enslaved Africans and later defended his remarks. New York Times, “Bible Backed Slavery, Says a Lawmaker,” May 10, 1996; see also George W. Gayle, “Letter to the Editor,” Montgomery Advertiser, May 30, 2007; Pat Buchanan, “A Brief for Whitey,” March 2008. Records from the era paint a much different picture, revealing American slavery as a system that was always dehumanizing and barbaric, and often bloody, brutal, and violent.

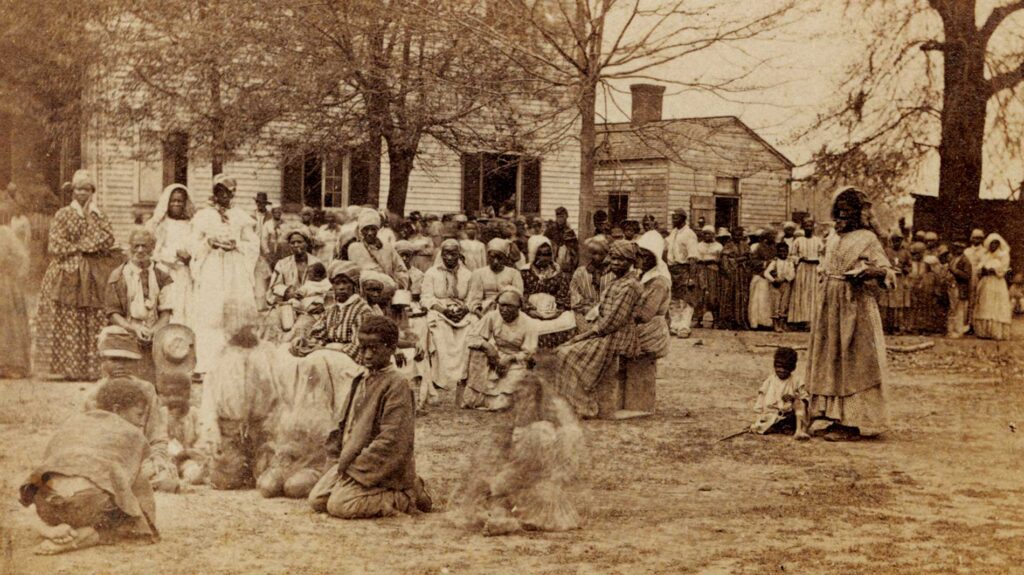

As an institution, slavery deprived the enslaved of any legal rights or autonomy and granted the enslaver complete power over the Black men, women, and children legally recognized as his property. Structurally, this weakened enslaved people’s claims to even the most basic social bond: the family. Marriages between enslaved people were not recognized by the law and required the permission of enslavers, who could force enslaved people to marry against their will. Once married, husbands and wives had no ability to protect themselves from being sold away from each other, and if enslaved by different people, were often forced to reside on separate plantations. Parents could do nothing when their young children were sold away,23 “Nearly two-thirds of all Appalachian slave sales separated children from their families—70 percent of these forced migrations occurring when they were younger than fifteen.” Wilma A. Dunaway, The African-American Family in Slavery and Emancipation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 67-68. and enslaved families were regularly and easily separated at an enslaver’s or auctioneer’s whim, never to see each other again.24 Heather Andrea Williams, “How Slavery Affected African American Families,” Freedom’s Story.

Slavery deprived the enslaved of any legal rights or autonomy and granted the enslaver complete power over the Black men, women, and children legally recognized as his property.

White men and women justified this cruelty by claiming Black people did not have emotional ties to each other. “It is frequently remarked by Southerners, in palliation of the cruelty of separating relatives,” observed one visitor to the South in the 1850s, “that the affection of negroes for one another are very slight. I have been told by more than one lady that she was sure her nurse did not have half the affection for her own children that she did for her mistress’s.”25 J. C. Benton, Through Others’ Eyes: Published Accounts of Antebellum Montgomery, Alabama, (Montgomery, AL: New South Books, 2014), 105.

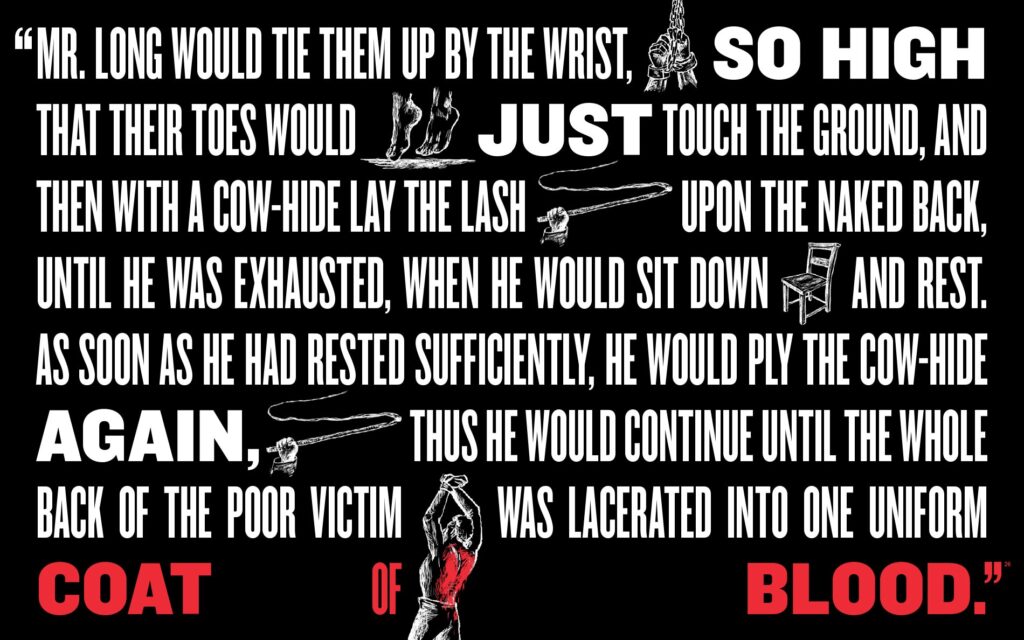

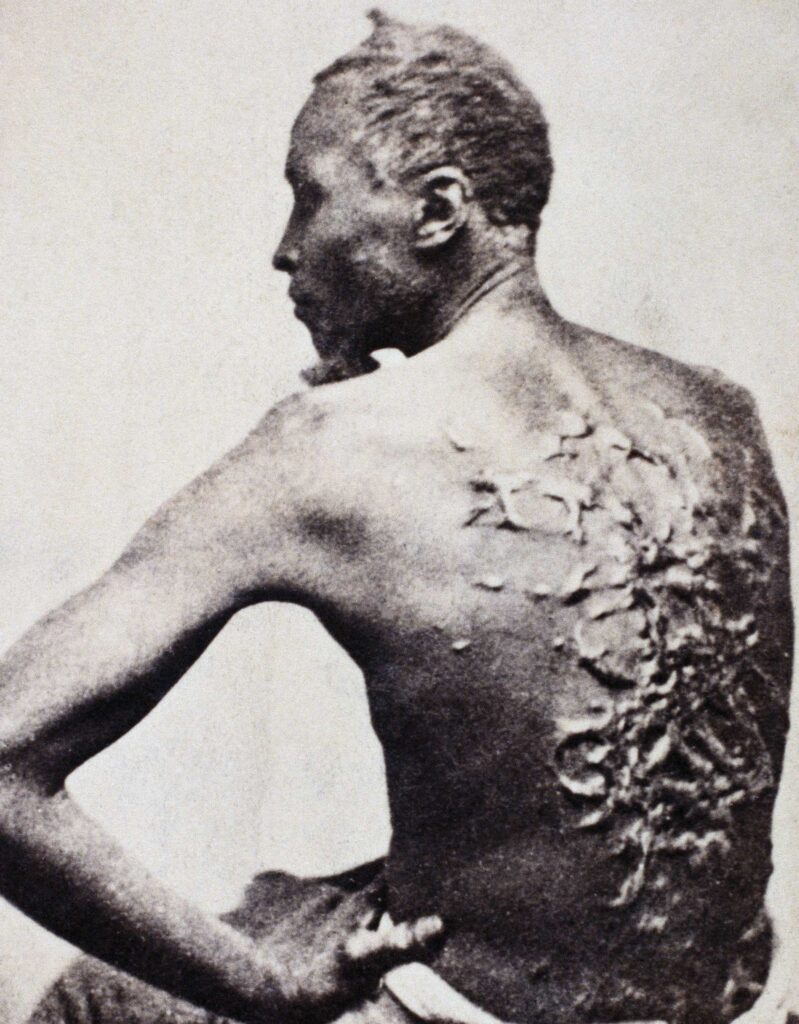

In a firsthand account published by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839, a Kentucky woman told the story of two young Black men, Ned and John, who were frequently severely whipped as punishment for “staying a little over the time with their wives” living on different plantations nearby: “Mr. Long would tie them up by the wrist, so high that their toes would just touch the ground, and then with a cow-hide lay the lash upon the naked back, until he was exhausted, when he would sit down and rest. As soon as he had rested sufficiently, he would ply the cow-hide again, thus he would continue until the whole back of the poor victim was lacerated into one uniform coat of blood.”26 Theodore Dwight Weld, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1839), 50. Both men died young, from illness brought on by this abuse.

In addition to the labor exploitation inherent to slavery, enslavers had the power to sexually exploit the enslaved people they held, both male27 “[S]exual assault of enslaved men took a wide variety of forms, including outright physical penetrative assault, forced reproduction, sexual coercion and manipulation, and psychic abuse.” Thomas A. Foster, “The Sexual Abuse of Black Men Under American Slavery,” J. of the Hist. of Sexuality (September 2011): 447. and female. Sexual abuse of enslaved Black men included being forced to have sex with enslaved women against their will and in front of a white audience. In 1787, two white enslavers in Maryland forced an enslaved Black man, at gunpoint, to rape a free Black woman; when the act was done, one of the white men likened the act to breeding horses.28 Ibid., 445.

In its most prevalent form—the rape of enslaved Black women by white enslavers—sexual abuse often resulted in the birth of biracial children who were also enslaved. As property, enslaved Black women were not protected by the law and had no refuge from sexual violence.

In 1855, a 19-year-old enslaved Black woman named Celia stood trial for killing Robert Newsom, a white enslaver who had purchased Celia five years earlier. Newsom raped her regularly and repeatedly, resulting in the birth of one child.29 Douglas O. Linder, Celia, A Slave, Trial (1855): An Account (2011). After repeated entreaties to the enslaver’s daughter led nowhere, Celia took action. When Newsom came to her cabin seeking sex on the night of June 23, 1855, Celia told authorities, she clubbed him over the head twice with a large stick, killing him.30 Ibid. The court concluded an enslaved Black woman had no right to defend herself against sexual attack, and an all-male, all-white jury convicted Celia of murder.31 Ibid. Sentenced to death, she was hanged on December 21, 1855.32 Ibid.

“To be a man, and not to be a man—a father without authority—a husband and no protector—is the darkest of fates. Such was the condition of my father, and such is the condition of every slave throughout the United States: he owns nothing, he can claim nothing. His wife is not his: his children are not his; they can be taken from him, and sold at any minute, as far away from each other as the human fleshmonger may see fit to carry them. Slaves are recognised as property by the law, and can own nothing except by the consent of their masters. A slave’s wife or daughter may be insulted before his eyes with impunity. He himself may be called on to torture them, and dare not refuse. To raise his hand in their defence is death by the law. He must bear all things and resist nothing. If he leaves his master’s premises at any time without a written permit, he is liable to be flogged. Yet, it is said by slave holders and their apologists, that we are happy and contented.”33 John S. Jacobs, “A True Tale of Slavery,” The Leisure Hour: A Family Journal of Instruction and Recreation, February 1861.

John S. Jacobs, 1815-1875, was enslaved in North Carolina as a child and escaped to freedom in adulthood.

Finally, enslaved people frequently suffered extreme physical violence as punishment for or warning against transgressions like running away, failing to complete assigned tasks, visiting a spouse living on another plantation, learning to read, arguing with white people, working too slowly, possessing anti-slavery materials, or trying to prevent the sale of their relatives.34 “When angry, masters frequently kicked, slapped, cuffed, or boxed the ears of domestic servants, sometimes flogged pregnant women, and often punished slaves so cruelly that it took them weeks to recover. Many slaves reported that they were flogged severely, had iron weights with bells on them placed on their necks, or were shackled.” Blassingame, The Slave Community, 261.

Because enslavers faced no formal prohibition against maiming or killing the enslaved, an enslaved person’s life had no legal protection; for some enslavers, this led to reckless disregard for life and horrific levels of cruelty. In Charleston, South Carolina, in 1828, an enslaver flogged an enslaved 13-year-old girl as punishment, then left her on a table in a locked room with her feet shackled together. When he returned, she had fallen from the table and died. The enslaver faced no consequence; under local law, “the slave was [his] property, and if he chose to suffer the loss, no one else had anything to do with it.”35 Weld, American Slavery As It Is, at 54 When an enslaved Black man named Moses Roper ran away from bondage in North Carolina, his enslaver whipped him with more than a hundred lashes, then covered his head in tar and lit it afire. When Moses escaped from leg irons, his enslaver had the nails of his fingers and toes beaten off.36 Blassingame, The Slave Community, 261.

Enslaved people frequently suffered extreme physical violence as punishment for or warning against transgressions like running away, failing to complete assigned tasks, visiting a spouse living on another plantation, learning to read, arguing with white people, working too slowly, possessing anti-slavery materials, or trying to prevent the sale of their relatives.

Even very young children were not safe from brutal abuse. In a letter to a cousin, a white woman enslaver described the killing of an infant. “Gross has killed Sook’s youngest child,” she wrote. “[B]ecause it would not do its work to please him he first whipt it and then held its head in the [creek] branch to make it hush crying.”37 “Conditions of Antebellum Slavery, 1830–1860,” Africans in America: PBS.org.

In May 1857, after a white family in Louisville, Kentucky, was murdered and their home destroyed by fire, four enslaved Black men were accused of the crime and stood trial. After an all-white jury found the men innocent of the charges, an enraged mob of local white men armed with a cannon attacked the jail and overtook the building. Facing the threat of death at the hands of the bloodthirsty mob, one of the four enslaved men cut his own throat in terror; the mob beat, stabbed, and hanged the other three Black men to death.38 Detroit Daily Free Press, “Terrible Mob in Louisville – Three Negroes Hung,” May 19, 1859.

As illustrated by this and many similar accounts, enslaved Black people faced the constant threat of attack, abuse, and murder under the system of American slavery, which devalued their lives, ignored their human dignity, and offered no protection under the law. Long after slavery ended, racialized attacks and racial terror lynchings like these continued, fueled by the same myth of racial inferiority previously used to justify enslavement.

Enslaved Black people faced the constant threat of attack, abuse, and murder under the system of American slavery, which devalued their lives, ignored their human dignity, and offered no protection under the law.

The Poor Slave’s Own Song

—

Farewell, ye children of the Lord,

To you I am bound in the cords of love.

We are torn away to Georgia,

Come and go along with me.

Go and sound the jubilee, &c.

To see the wives and husbands part,

The children scream, they grieve my heart;

We are sold to Louisiana,

Come and go along with me.

Go and sound, &c.

Oh! Lord, when shall slavery cease,

And these poor souls enjoy their peace?

Lord, break the slavish power!

Come, go along with me.

Go and, sound, &c.

Oh! Lord, we are going to a distant land,

To be starved and worked both night and day;

O, may the Lord go with us;

Come and go along with me.

Go and sound, &c.39 William J. Anderson, Life and Narrative of William J. Anderson, Twenty-four Years a Slave; Sold Eight Times! In Jail Sixty Times!! Whipped Three Hundred Times!!! or The Dark Deeds of American Slavery Revealed. Containing Scriptural Views of the Origin of the Black and of the White Man. Also, a Simple and Easy Plan to Abolish Slavery in the United States. Together with an Account of the Services of Colored Men in the Revolutionary War–Day and Date, and Interesting Facts (Chicago: Daily Tribune, 1857), 80-81.

The Domestic Slave Trade in America

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the United States acquired great swaths of land to the south of the original 13 colonies. White settlers in search of cheap, fertile land began to move to this area from states in the Upper South, including North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and Kentucky. These settlers brought with them enslaved Black people to work the land and care for their homes.40 Robert H. Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce: The Transformation of the Interstate Slave Trade (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 8. By the 1790s, the invention of the cotton gin allowed for increased production, and the rising price of cotton created incentives for settlers to expand their plantations and their supply of enslaved workers. In territories that would later become the Lower South states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida, the demand for enslaved Black people skyrocketed.41 Adam Rothman, “The Domestication of the Slave Trade in the United States,” in The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 33; Frederic Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 8, 11.

After Congress outlawed the Transatlantic Slave Trade beginning in 1808,42 Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South, 67; Rothman, “The Domestication of the Slave Trade in the United States,” 40. growing demand for enslaved Black laborers had to rely on natural reproduction in the local enslaved population, or the sale of enslaved people from one state to another. Over the next half century, this “Domestic Slave Trade” became ubiquitous across the South and central to the debate over whether to abolish slavery.

An estimated one million enslaved people were forcibly transferred from the Upper South to the Lower South between 1810 and 1860.43 David L. Lightner, Slavery and the Commerce Power: How the Struggle Against the Interstate Slave Trade Led to the Civil War (Chelsea, MI: Sheridan Books, 2006), 6; Steven Deyle, “The Domestic Slave Trade in America: The Lifeblood of the Southern Slave System,” in The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 93. By the time Alabama became a state in 1819, the Domestic Slave Trade was booming. Over the next 40 years, the enslaved population in Alabama increased from 40,000 to 435,000.44 James Benson Sellers, Slavery in Alabama (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1950), 147.

The most prominent reason for the forced transfer of so many enslaved people from the Upper to the Lower South was the economy. Due to the booming cotton industry, enslaved Black people were worth more in the Lower South than anywhere else in the country—and they were also a more secure investment in the Lower South, where they had less chance to escape to freedom in the North.45 Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce, 28-29. Forced abolition was less of a threat in the Lower South where, in comparison to the Upper South, there was much less political will or popular support for creating legal prohibitions on slavery.

The Domestic Slave Trade brought economic benefits to the entire South, but it also challenged the myth of benign slavery. Under that myth, white enslavers and enslaved Black people enjoyed an organic, mutually beneficial relationship in which the enslaver profited from the labor and the enslaved enjoyed the enslaver’s food, clothing, shelter, protection, and civilizing influence.51 Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce, 9, 41. Prior to the growth of the Domestic Slave Trade, this myth faced little dispute because only enslavers, overseers, and the enslaved witnessed the brutal, day-to-day reality of slavery. As the Domestic Slave Trade grew, however, growing numbers of Southerners and travelers from the North had the chance to witness the system’s inhumanity.

Trafficking enslaved people relied on the sale of human beings as commodities, but its tragic scenes highlighted the humanity of those in bondage.52 Ibid., 48. Throughout the South, urban and rural communities alike witnessed exhausted and dejected enslaved people chained together and whipped as they marched hundreds of miles to be sold. They heard the screams and saw the tears of enslaved people torn from their homes and sold to the highest bidder. They shopped and worked amidst enslaved people publicly confined in pens resembling dungeons, alongside livestock in filthy conditions. Press accounts documented the heartbreaking stories of enslaved mothers who jumped from buildings and enslaved fathers who slit their throats rather than be separated from their families.

Jourden Banks, a Black man who was enslaved in Alabama before escaping to freedom, published a book in 1861 recounting his experiences. While being held for sale in Richmond, Virginia, he recalled,

…I saw things I never wish to see again. [The jail] was so constructed, I should think, as to hold some two or three hundred. There are no beds, or comfortable means of lodging either men, women, or children. They have to lie or sit by night on boards. The food is of the coarsest kind. Sales take place every day. And oh, the scenes I have witnessed! Husbands sold, and their wives and children left for another day’s auction; or wives sold one way, and husbands and fathers another, at the same auction. The distresses I saw made a deep impression upon my mind, My attention was diverted from myself by sympathy with others.53 Jourden H. Banks, A Narrative of Events of the Life of J.H. Banks, an Escaped Slave, from the Cotton State, Alabama, in America (Liverpool: M. Rouke, 1861).

This clearly exploitative treatment of enslaved people undermined the claim that slavery benefitted the enslaved.

Perhaps due to the economic and geographic differences between the regions, the Upper and Lower South developed differing views of the Domestic Slave Trade. In the Upper South, the trafficking of enslaved people was viewed with a mix of support and scorn,54 Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told, 67. and a small minority of white people questioned whether the system’s brutality warranted outlawing it altogether.55 Ibid., 63. In contrast, residents of the Lower South generally accepted human trafficking as proper and necessary, and very few expressed any concern for the enslaved.56 Ibid., 95.

Despite these differing attitudes, trafficking benefitted both the Upper and Lower South economically.57 Steven Deyle, Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 95. The Upper South received high sales revenue for the enslaved people sold to the Lower South, and used the threat of that region’s harsher work conditions to control and discipline the enslaved people who remained.58 The threat of sale to the Lower South was key to controlling enslaved people, perhaps more than the whip, because it relied on terror rather than torture. Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce, 44. In the Lower South, enslaved laborers were forced to work long hours under harsh conditions for no pay, allowing landowners to maximize their profits and accumulate unprecedented wealth. Thus, even amid clear evidence of slavery’s inhumanity, the symbiotic economic relationship between the two Southern regions solidified most white Southerners’ allegiance to slavery.59 Deyle, Carry Me Back, 92.

Throughout the South, defenders of slavery rejected critics’ characterization of human trafficking as barbaric and cruel and insisted that the documented horrors of bondage were imagined or exaggerated.60 Ibid., 92, 109. These pro-slavery advocates took to national platforms to assure Americans that enslaved people were primarily sold locally and had the opportunity to choose their new enslavers, and that efforts were made to keep families together. In reality, most enslaved people were sold without a single other family member;61 Michael Tadman, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 130. it is estimated that more than half of all enslaved people in the Upper South were separated from a parent or child through sale, and a third of all marriages of enslaved people were destroyed by forced migration.62 Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce, 42.

It is estimated that more than half of all enslaved people in the Upper South were separated from a parent or child through sale, and a third of all marriages of enslaved people were destroyed by forced migration.

Proponents of slavery also claimed that enslavers only sold enslaved people out of necessity—to satisfy an insurmountable debt or respond to dangerous misbehavior by the enslaved. In fact, only a small percentage of enslaved people were traded due to economic hardship or attempts to escape;63 Tadman, Speculators and Slaves, 129. in most cases, enslavers of the Upper South sold enslaved people to gain supplemental income.64 Ibid.

Pro-slavery advocates also tried to separate inhumane trafficking from the “humane” institution of slavery by scapegoating traffickers as individually responsible for any brutal treatment of enslaved people. While traffickers indeed committed myriad forms of abuse against the enslaved, including raping enslaved women,65 Ibid., 184-85; Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce, 75. enslavers did, too—and the Southern social system did nothing to discourage this behavior. Despite their reputation for brutality, traffickers were generally among “the wealthiest and most influential” citizens in their communities.66 Tadman, Speculators and Slaves, 137.

Despite their reputation for brutality, traffickers were generally among “the wealthiest and most influential” citizens in their communities.

Human traffickers accumulated substantial wealth by purchasing the enslaved in the Upper South and transporting them to the Lower South. Transporting enslaved people on foot was considered the “simplest” way because it required only a horse, a mule, a wagon, and a whip.67 Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce, 15. Traffickers lined up enslaved adult Black men in pairs, handcuffed them together, and then ran a long chain through all of the handcuffs.68 Lightner, Slavery and the Commerce Power, 10. These arrangements were called “coffles.”69 Anthony Gene Carey, Sold Down the River: Slavery in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley of Alabama and Georgia (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2011), 53. Enslaved Black women and older Black children marched behind the men, and the smallest children and the sick rode in a wagon at the rear.

The overland march was common and brutal. One trek could last months and exceed one thousand miles.70 Lightner, Slavery and the Commerce Power, 10. The enslaved were forced to march quickly for hours until they dropped in the road, and those who fell risked being slashed to pieces by long whips.71 Carey, Sold Down the River, 53. Traffickers often sold enslaved people as they moved from one community to another along their route, and coffles became a common sight across the South.72 Sellers, Slavery in Alabama, 154-55; Jeffrey C, Benton, The Very Worst Road: Travelers’ Accounts of Crossing Alabama’s Old Creek Indian Territory, 1820-1847 (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2009), 125.

Traffickers lined up enslaved adult Black men in pairs, handcuffed them together, and then ran a long chain through all of the handcuffs.

Beginning in the 19th century, the introduction of new methods of transportation began to alter the routes used by traffickers. The arrival of the steamboat in 1811 allowed traffickers to send the enslaved from markets along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana.73 Enslaved people would be transported in coffles to the port of departure. Lightner, Slavery and the Commerce Power, 10. The steam locomotive arrived in the 1830s and by the 1840s and 1850s, rail lines stretched across the South. Often cleared, constructed, and maintained by enslaved labor, these rail lines became a preferred method for transporting the enslaved to the Lower South. Trips that took weeks by foot now took less than two days by rail.74 Ibid.

Cleared, constructed, and maintained by enslaved labor, these rail lines became a preferred method for transporting the enslaved to the Lower South. Trips that took weeks by foot now took less than two days by rail.

These changes in transportation transformed Montgomery, Alabama, from one of many stops along the overland route to a primary trading market. In 1847, a direct steamboat line was established between New Orleans and Montgomery,75 J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978), 275. allowing Montgomery to rival Mobile, Alabama, as a center for trading in enslaved Black people.76 Ibid.; Sellers, Slavery in Alabama, 152; Interview with Mary Ann Nealy, Historian, in Montgomery, Ala. (Jan. 30, 2013).

In 1851, enslaved people bought by the State of Alabama constructed a rail line to connect Montgomery to Atlanta, Georgia.77 Jeffrey C. Benton, A Sense of Place: Montgomery’s Architectural Heritage (Montgomery, AL: River City Publishing, 2001). As more and more traffickers utilized this rail system, hundreds of enslaved people began arriving at the Montgomery train station each day.78 Sellers, Slavery in Alabama, 153. Now connected to the rest of the South by boat and by rail, Montgomery became Alabama’s principal market for enslaved people.79 Ibid., 154; Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South, 298.

Acknowledgments

This report is written, researched, designed, and produced by the staff of EJI. We would like to specially thank Hanna Kim for design and illustration and extend thanks to Bryan G. Stevenson, Ben Maxymuk, Mark Feldman, Brittany Francis, and Human Pictures for photography.

Bryan Stevenson, Director