Racial Terror Massacre

Eufaula, Alabama

During the Civil War, Eufaula, Alabama, was at once a Confederate stronghold, the commercial center of Barbour County, and home to more Black people than white. After Emancipation, ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed voting rights for Black men. This empowered Barbour County’s new Black electorate to end white supremacist officials’ control over the county. In 1870, Black voters helped elect Elias Keils, a white candidate who supported the aims of Reconstruction, to the position of City Court Judge.1 Melinda M. Hennessey, “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874,” Alabama Historical Quarterly 38, no. 2 (Summer 1976), 112-113; Dan T. Carter, The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of theNew Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 35-36. Four years later, when Keils ran for re-election, local white residents determined to regain political dominance in the county used terror and intimidation to suppress Black votes, ultimately waging a deadly massacre that left dozens of Black people dead.2 See Report on the Alabama Election of 1874, House Reports, no. 262, 43rd Cong., 2nd Sess. (Washington, 1875); Report on the Election in Alabama, Senate Reports, no. 704, 44th Cong., 2nd Sess. (Washington, 1877). Hereafter these sources are referred to as House and Senate Report and they are cited as the person testifying, the report, and then page number.

As the 1874 election neared, white employers openly fired any Black workers who intended to vote for Keils.3 Lazarus Gardner, House Report, 804; Lawrence Bowen, House Report, 814; Edwin Odon, House Report, 972. False rumors spread that Black residents planned to violently drive white voters from the polls, and white residents began stockpiling guns near Eufaula polling sites.4 A. S. Daggett, House Report, 598; Eli Shorter, House Report, 800; Henry Frazer, House Report, 214-215; Elias Keils, House Report, 2-3. Seeing the threat of election day violence, Keils tried to notify state and federal officials of the danger, but Alabama’s Attorney General rebuffed the warning and A.S. Daggett, captain of federal troops stationed in Eufaula, claimed it would violate his orders to use federal soldiers to protect Black voters.5 Daggett, House Report, 598; Hennessy, 115-116.

Despite the risk, hundreds of African Americans marched to the downtown Eufaula polling site on November 3. Some were immediately arrested and jailed on fraud accusations.6 Odon, House Report, 966-967; Gardner, House Report, 804. Hennessey, House Report, 117; Carter, House Report, 37. Around noon, several white men forced a Black man into an alley and threatened to arrest him if he did not vote against civil rights. Black witnesses protested and a pistol was fired—white people claimed a Black man had fired a shot at them while many Black people insisted a white man had fired a shot into the air. Soon afterward, a large mob of white men retrieved stockpiled guns stored nearby, gathered in the street and in the upstairs windows of surrounding buildings, and fired “indiscriminately” into the crowd of mostly unarmed Black voters.7 See Williford, House Report, 428; Williford, Senate Report, 445-446; Maurice Seals, House Report, 814-815; Hamilton, House Report, 817; Aaron Hunter, House Report, 831; Odon, House Report, 966-67; Williams, House Report, 979.

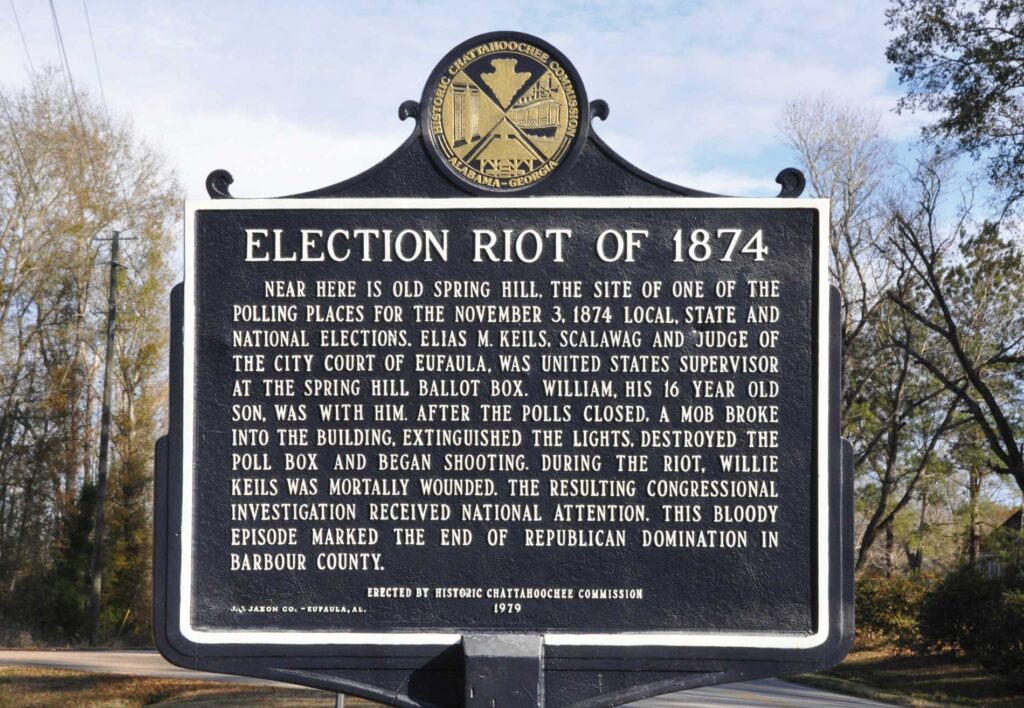

A historical marker in Barbour County, Alabama, erected in 1979, describes the 1874 Eufaula Massacre as a “riot.”

Jonathan Gibson

Within minutes, 400 shots had been fired, leaving at least six Black people dead and injuring as many as 80 people.8 Williford, House Report, 427-28; Williams, House Report, 978; Daggett, House Report, 597; Hamilton, House Report, 817; Bowen, House Report, 814; Frazer, House Report, 216. Many survivors fled, including an estimated 500 Black people who had not yet voted.9 Daggett, House Report, 597-598; see Keils, House Report, 5. One Black man who survived later recalled that, when the shooting stopped, he heard the white crowd cheer, “Hurrah for the white man’s party.”10 Hamilton, House Report, 817. Later that day, a white mob attacked another county polling station in Spring Hill, Alabama, where Keils was the election supervisor. The mob destroyed the ballot box, burned the ballots inside, and killed Keils’s teenage son.11 Keils, House Report, 4.

Newspapers described the violence as a “riot,” but a Congressional representative later characterized the attack as a massacre.12 See Senate Report, 577; Williford, House Report, 433. Sentiments published in the local white press praised the attack: “Big riot today. Several killed and many other hurt—some badly—but none of our friends among them. The white man’s goose hangs high. Three cheers from Eufaula.”13 Montgomery Morning News, “Special to Morning News,” November 4, 1874, quoted in Congressional Report, 1278; The Weekly Advertiser, “Eufaula Riot,” February 25, 1874; Wisconsin State Journal, “Election Fights,” November 5, 1874; The Burlington Free Press, November 5, 1874; National Republican, November 10, 1874. Although the identities of many white perpetrators of the massacre were known, no white person was ever convicted. Instead, a Black man named Hilliard Miles was convicted and imprisoned for perjury after identifying members of the white mob.14 State grand juries failed to indict the perpetrators but a federal grand jury brought 30 indictments including the one against Miles. James L Pugh, Senate Report, 1860-61, 1871-1972; A.E. Williams, Senate Report, 618; The Livingston Journal, November 27, 1984; The Montgomery Advertiser, November 24, 1874; Hennessey, “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874,” 123-124; Carter, The Politics of Rage, 36-37. Decades later, Braxton Bragg Comer, whom Mr. Miles had named as a perpetrator of the massacre, was elected governor of Alabama.15 Carter, The Politics of Rage, 36-37.

The Eufaula Masssacre and its aftermath showed Black residents that exercising their new legal rights—particularly by voting—made them targets for deadly attacks and they could not depend on authorities for protection.16 Keils, House Report, 1148; “Views of the Minority,” House Report, LXVIII-LXIX. The result was mass voter suppression. While 1,200 Black Eufaula residents voted in the 1874 election, only 10 cast ballots in 1876. That legacy remains.17 Carter, The Politics of Rage, 37. Today, the population of Barbour County is nearly 50 percent Black but white officials hold 8 of 12 elected county positions. In 2016, the county had the highest voter purge rate in the United States.18 Max Garland, Alex Amico, Ali Schmitz, Phillip Jackson, and Pam Ortega, “African-Americans in the South face new barriers to vote,” VotingWars News21, August 20, 2016. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, “voter purges are an often-flawed process of cleaning up voter rolls by deleting names from registration lists. While updating registration lists as voters die, move, or otherwise become ineligible is necessary and important, when done irresponsibly — with bad data or when two voters are confused for the same person — the process can knock eligible voters off the roll en masse, often with little notice. Many voters discover they’re no longer listed only when they arrive at the polling place. As a result, many eligible Americans either don’t vote or are forced to cast provisional ballots.” See Brennan Center, “Voter Purges.”

During Reconstruction, Black voters lost their lives in Eufaula and many more were disenfranchised because they supported pro-Reconstruction Republican candidates who pushed for Black citizenship rights at a time when white supremacy dominated the Southern Democratic party. This division would continue until major party realignments during the 20th century civil rights movement. Today, public memory of Reconstruction violence in Barbour County is reduced to one historical marker erected in 1979, which describes the “Election Riot of 1874” as a “bloody episode that marked the end of Republican domination in Barbour County.” In downtown Eufaula, the streets where Black voters were shot down for voting more than 140 years ago now host a towering Confederate monument erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1904. S.H. Dent, a former Confederate soldier who witnessed and possibly helped commit the massacre, spoke at the monument’s unveiling.19 The Times and News (Eufaula, Ala.), “The Biggest Day,” Dec. 1, 1904; S.H. Dent, House Report, 803.

In Eufaula today, a Confederate monument stands in the same area where Black voters were massacred in 1874.

Jonathan Gibson