Sidebar

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

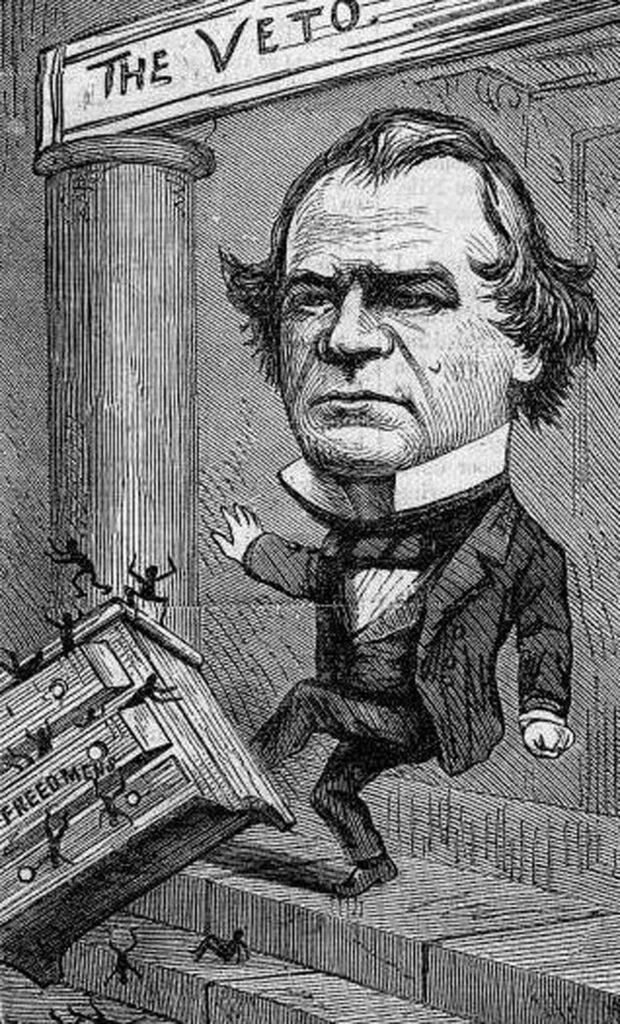

Thomas Nast political cartoon depicting President Andrew Johnson’s attempt to veto the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Harper's Weekly, 1866

Vice President Andrew Johnson was elevated to the presidency in April 1865 after a Confederate sympathizer assassinated President Abraham Lincoln soon after the end of the Civil War. Progressive federal officials were initially optimistic that President Johnson would prioritize protecting the rights of emancipated Black people and hold Southern states accountable for secession, 1 Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1989).but that hope was short-lived.

Within one month of taking office, President Johnson—a former slave holder from Tennessee—issued an amnesty proclamation granting full pardons “to all white persons who have, directly or indirectly, participated in the existing rebellion.”2 “Proclamation Pardoning Persons Who Participated in the Rebellion,” May 28, 1865. That same day, he formally recognized state governments in Tennessee, Virginia, Arkansas, and Louisiana, even though they remained largely controlled by former Confederate officials.3 Frank O. Bowman III, High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 156.

In his first State of the Union Address later that year, Johnson announced that he would only require the former Confederate states to accept the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery in order to “resume their places in the two branches of the National Legislature” and “complete the work of restoration.”4 Andrew Johnson, First Annual Message, December 4, 1865. Johnson explicitly refused to require voting rights for Black people and instead left states to decide their own electoral policies.5 Ibid. He also ignored the pleas of a delegation led by Frederick Douglass, who “took exception” to Johnson’s “entirely unsound and prejudicial” views on Black voting rights.6 Frederick Douglass, Reply of the Colored Delegation to the President, February 7, 1866.

Progressive officials like Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts argued that lenient treatment of the former Confederate states would undermine abolition and Black citizenship.7 New York Times, “Thaddeus Stevens on the Great Topic of the Hour,” September 6, 1865. “If we leave [freed Black people] to the legislation of their late masters,” Rep. Stevens remarked, “we had better left them in bondage.”8 Thaddeus Stevens, Speech, December 18, 1865. Indeed, Southern states quickly sought to re-establish enslavement by constitutional means, including convict leasing and sharecropping.

The Johnson Administration’s disregard for Black civil rights also may have emboldened white mobs to wage increasingly violent terror campaigns against Black people throughout the South, including in cities like Memphis9 See Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the late riots in the city of Memphis made by Col. Charles F. Johnson, Inspector General States of Kentucky and Tennessee and Major T.W. Gilbreth, A.D.C. to Major General Howard, Commissioner Bureau R.F.&A. Lands,” May 7, 1866. and New Orleans.10 See James G. Hollandsworth Jr., An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001); Donald E. Reynolds, “The New Orleans Riot of 1866, Reconsidered,” J. La. Hist. Assoc.(Winter 1964). Rather than condemn the violence, Johnson pardoned thousands of secessionists and blamed the bloodshed on “the Radical Congress”—federal representatives who favored laws enforcing Black rights.11 Articles of Impeachment, March 4, 1868.

Northern outrage at Johnson’s rhetoric helped progressive candidates win a supermajority in Congress, which overrode his vetoes of radical legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. To prevent Johnson from removing key executive officials, Congress in 1867 passed over presidential veto the Tenure of Office Act, which required Congressional approval for any presidential removal of an executive officeholder.12 Tenure of Office Act, March 2, 1867. Johnson violated the law twice within a year, and in February 1868, Reps. Stevens and John Bingham proposed an impeachment resolution.13 Articles of Impeachment, March 4, 1868.

Although the official charges hinged on Johnson’s removal of executive officers, his opposition to meaningful Reconstruction was clearly a strong motivation for Congress’s action. “[T]he bloody and untilled fields of the ten unreconstructed states, the unsheeted ghosts of the two thousand murdered negroes in Texas, cry, if the dead ever evoke vengeance, for the punishment of Andrew Johnson,” declared Rep. William D. Kelley of Pennsylvania.14 L. P. Brockett, Biographical Sketches of Patriots, Orators, Statesmen, Generals, Reformers, Financiers and Merchants, Now on the state of Action: Including Those Who in Military, Political, Business and Social Life, are the ProminentLeaders of the Time in This Country (Philadelphia: Ziegler & McCurdy, 1872), 501.

The House of Representatives quickly approved the impeachment resolution by a vote of 126 to 47.15 Edward McPherson, A Handbook of Politics (Washington D.C.: Philip & Solomon, 1868). A week later it issued 11 articles of impeachment.16 Articles of Impeachment, March 4, 1868. The Senate trial characterized the Congressional battle with Johnson as “one of the last great battles against slavery”17 “Testimony of Sen. Henry Wilson,” Trial of Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, Before the Senate of the United States, on Impeachment by the House of Representatives for High Crimes and Misdemeanors, Vol. III(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1868).—but he was spared removal from office by one vote. Johnson remained president for the few months remaining in the term, and Ulysses S. Grant won the 1868 election.

To the end of his presidency, Johnson continued to oppose Reconstruction and what he deemed “coercive” methods of protecting Black civil rights. “The attempt to place the white population under the domination of persons of color in the South,” he said in December 1868 in his last State of the Union address, “has impaired, if not destroyed, the friendly relations that had previously existed between them; and mutual distrust has engendered a feeling of animosity which, leading in some instances to collision and bloodshed, has prevented the cooperation between the two races so essential to the success of industrial enterprise in the Southern States.”18 Andrew Johnson, State of the Union Address, December 25, 1868.

Today, Johnson remains the first of only three American presidents ever impeached while in office.