Sidebar

The Freedmen’s Bureau

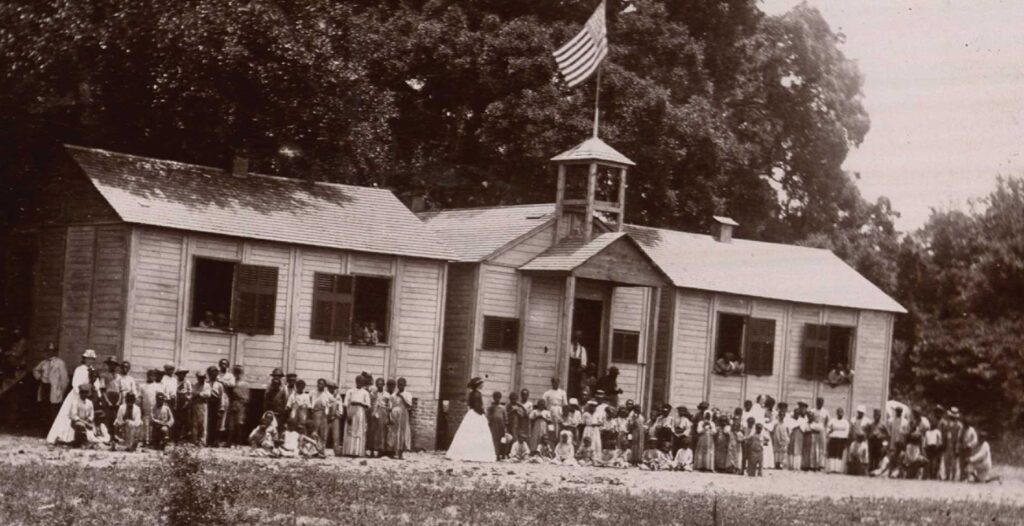

Students and teachers outside the Freedmen’s Bureau school on St. Helena’s Island, South Carolina, 1866.

In March 1865, Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide formerly enslaved people with basic necessities and to oversee their condition and treatment in the former Confederate states. In practice, the Bureau often fell short at this vast and historic undertaking, as white mobs and institutions throughout the South continued to oppress, attack, and exploit African Americans during Reconstruction. Local Bureau offices served as central community locations to document reports of violence committed against freed people, register Black people to vote, verify labor contracts between formerly enslaved people and employers, provide food and medical care, establish schools, and perform marriages.1 “An Act to establsh a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees,” March 3, 1865. The offices often faced both internal and external impediments to carrying out these functions.

Many of the Bureau’s difficulties began when it was established as a division of the War Department and authorized to operate for only one year after the war’s end. Congress appropriated no budget for the Bureau and instead left its staffing and funding to the military2 Foner, Reconstruction, 69.—an institution ill-suited for the task of overseeing the complex social restructuring required to counter the effects of centuries of enslavement and entrenched racial hierarchies. Some lawmakers proposed making the Bureau a permanent, independent agency or making it part of the Interior Department but those ideas met bipartisan opposition.3 Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 221. In 1866, President Johnson vetoed Congress’s first attempt to extend the Bureau’s operations beyond one year. The measure was rewritten and passed over a second veto.4 Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Atlantic, March 1901.

Bureau offices were poorly staffed and under-resourced, unable to cope with the numerous needs of formerly enslaved people still facing widespread violence and discrimination alongside the trauma and poverty borne of generations in bondage. The Bureau Commissioner’s office was responsible for overseeing operations in the entire former Confederacy with a staff of just 10 clerks. As of 1868, the Bureau had only 900 officials to serve millions of formerly enslaved people across the South.5 Ibid.

Local Bureau offices quickly became targets for racist violence. Many white people in the South saw the Bureau as a symbol of unjust federal occupation and resented that federal officials were working to assist formerly enslaved people while Southern white communities remained devastated by the failed Confederate rebellion. White Southerners greatly hindered the Bureau’s ability to enforce federal law by denying its authority. When two freedwomen brought a case against a white man named Maynard Dyson in Virginia in 1866, he ignored the Freedmen’s Court’s summons and refused to comply with the court’s order that he compensate the women. Dyson’s attitude was common, and strained resources rendered the Bureau largely powerless to force compliance.6 “Narrative Reports of Criminal Cases Involving Freedmen, Mar. 1866 – Feb. 1867,” Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865 – 1869 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives Microfilm Publication), M1048 Roll 59.

In many instances, white Southerners’ disregard for the Bureau escalated to violence against schools and teachers that educated Black children. In 1869, a white mob burned down a freedmen’s school in Clinton, Tennessee. A teacher later explained in a letter to the Bureau that, days before the fire, the school had raised the American flag to celebrate the recent presidential inauguration of former Union General Ulysses S. Grant.7 Paul David Phillips, “White Reaction to the Freedmen’s Bureau in Tennessee,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Vol. 25: No. 1, 1966), 55. Bureau records document many attacks on schools, including in Travis County, Texas;8 “Miscellaneous Records Relating to Murders and Other Criminal Offenses Committed in Texas 1865 – 1868,” Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Texas Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and AbandonedLands, 1865 – 1869 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives Microfilm Publication), M821 Roll 32. Queen Anne’s County, Maryland;9 “Miscellaneous Reports and Lists,” Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the District of Columbia Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865 – 1869 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives Microfilm Publication), M1055 Roll 21. and Rockbridge County, Virginia.10 “Records Relating to Murders and Outrages,” Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865 – 1869 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives Microfilm Publication), M1048 Roll 59. In 1868, the white owner of a Clarksville, Tennessee, building that freed people wanted to use for a school declared that he would rather “burn it to the ground than rent it for a ‘nigger school.’”11 Phillips, “White Reaction to the Freedmen’s Bureau in Tennessee,” 56.

In the face of waning political will to protect Black people’s lives and rights and under growing political pressure from the South, Congress unceremoniously dismantled the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1872—seven years after the war’s end, five years before the end of Reconstruction, and at the height of deadly violence targeting African Americans. Today the Bureau’s records supply some of the most detailed descriptions of the Reconstruction era, while also documenting the agency’s own shortcomings and failures.

“The passing of a great human institution before its work is done leaves a legacy of striving for other men,” W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1901.12 Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau.” While the Freedmen’s Bureau was launched as a federal effort to provide support and protection to formerly enslaved people as they struggled to exercise new freedoms, the inadequate and incomplete commitment to that purpose enabled fierce white resistance to undermine the Bureau’s effectiveness, and ensured that the work of protecting Black freedom would remain an unfulfilled task for years to come.