Racial Terror Massacre

Memphis, Tennessee

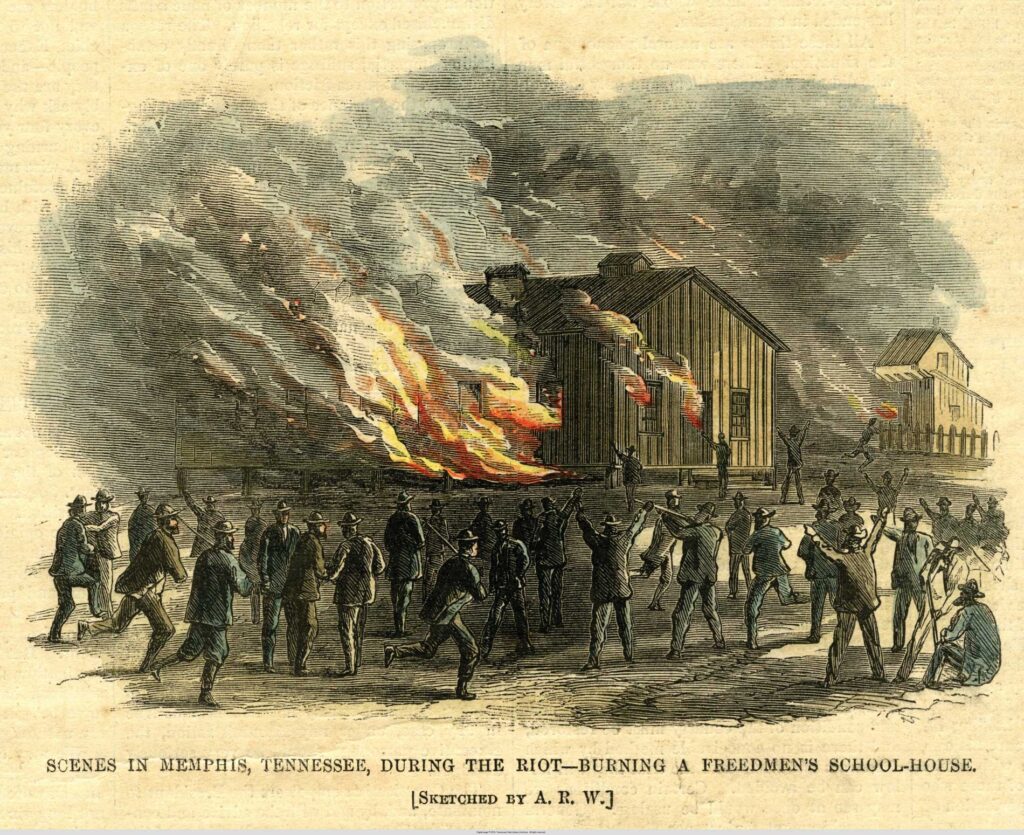

The Memphis Massacre.

Harper's Weekly, May 26, 1866

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Memphis and other large Southern cities became popular destinations for newly emancipated Black people in search of safety, resources, and opportunity. As the site of a Freedmen’s Bureau office and a base for federal troops, Memphis was a particularly sought-after location and it experienced a Black population surge.1 Ash, A Massacre in Memphis, 68-89.

Within a year of the war’s end, tensions in Memphis were high, particularly between white Irish immigrants—who comprised most of the city’s police force—and Black residents—who were regularly subjected to police harassment and brutality for appearing “suspicious.”2 Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the late riots in the city of Memphis made by Col. Charles F. Johnson, Inspector General States of Kentucky and Tennessee and Major T.W. Gilbreth, A.D.C. to Major General Howard, Commissioner Bureau R.F.&A. Lands,” May 7, 1866. White newspapers worsened this situation by encouraging white Memphis residents to view Black people as dangerous and lawless.3 “The general tone of certain city papers which in articles that have appeared almost daily, have councilled the low whites to open hostilities with the blacks.” Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of … the late riots in the city of Memphis…”

In May 1866, a group of Black Union soldiers in uniform were socializing on the streets of South Memphis days after they had been discharged when four white police officers ordered them to disperse.4 Ash, A Massacre in Memphis, 95. The frustrated soldiers refused to leave5 Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of … the late riots in the city of Memphis…”; U.S. Congress, Report of the House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, July 25, 1866. and the ensuing argument escalated into a shootout.6 Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of … the late riots in the city of Memphis…” No one was injured except a white officer who accidentally shot himself in the hand, but word of the conflict spread rapidly.7 Ibid; U.S. Congress, Report of the House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, July 25, 1866. Angry white mobs formed and proceeded to inflict terror on South Memphis, where the majority of Black people lived. City recorder John C. Creighton encouraged the deadly attack by telling the mob: “Boys, I want you to go ahead and kill every damned one of the nigger race and burn up the cradle.”8 Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of … the late riots in the city of Memphis…”

From May 1 to 3, white mobs indiscriminately beat, robbed, tortured, shot, raped, and killed Black men, women, and children. They also destroyed property and looted anything of value.9 U.S. Congress, Report of the House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, July 25, 1866. At least 90 Black homes were destroyed by fire, many with residents still inside, and the mobs burned down all of the city’s Black churches and schools.10 Ibid.

African American survivors later recounted the brutal violence to a Congressional committee formed to investigate the massacre. One woman testified that when her 16-year-old daughter, Rachel Hatcher, tried to save a neighbor from his burning home, a white mob surrounded the building and shot the young girl to death.11 Ibid. Another witness reported that a white mob shot guns into the Freedmen’s Hospital and injured patients, including a small, paralyzed child.12 Ibid.

African Americans received little protection from local authorities during the attacks, as the city’s mayor was reportedly drunk throughout the massacre13 Freedmen’s Bureau, “Report of … the late riots in the city of Memphis…” and many law enforcement officials joined the roving mobs.14 Ibid. “Instead of protecting the rights of persons and property as is their duty,” the Freedmen’s Bureau’s investigation later concluded, “[local police] were chiefly concerned as murderers, incendiaries, and robbers. At times they even protected the rest of the mob in their acts of violence.”15 Ibid. Union troops stationed in the city provided little help, claiming their forces were too small to take on the deadly white mobs.16 Ibid.

Even after the massacre’s toll of death and destruction was revealed, Memphis’s white community refused to take responsibility. A Freedmen’s Bureau investigation reported that most white people only regretted the financial costs of the violence.17 Ibid. An editorial in The Memphis Argus, a white-owned newspaper, declared, “The whole blame of this most tragical and bloody riot lies, as usual, with the poor, ignorant, deluded Blacks.” The paper attributed the massacre to Black gun ownership:

[W]e cannot suffer the occasion to pass without again calling the attention of the authorities to the indispensable necessity of disarming these poor creatures, who have so often shown themselves utterly unfit to be trusted with firearms. On this occasion the facts all go to show that but for this much-abused privilege accorded to them by misguided and misjudging friends, there would have been no riot. . . . The universal questions asked on all corners of the streets is, “Why are not the negroes disarmed?”18 Memphis Argus, “The Reign of Bloodshed,” May 2, 1866.

No white people were ever held legally accountable for their participation in the Memphis Massacre.19 U.S. Congress, Report of the House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, July 25, 1866.